56.2 Brain Stimulation

56-

Please continue to the next section.

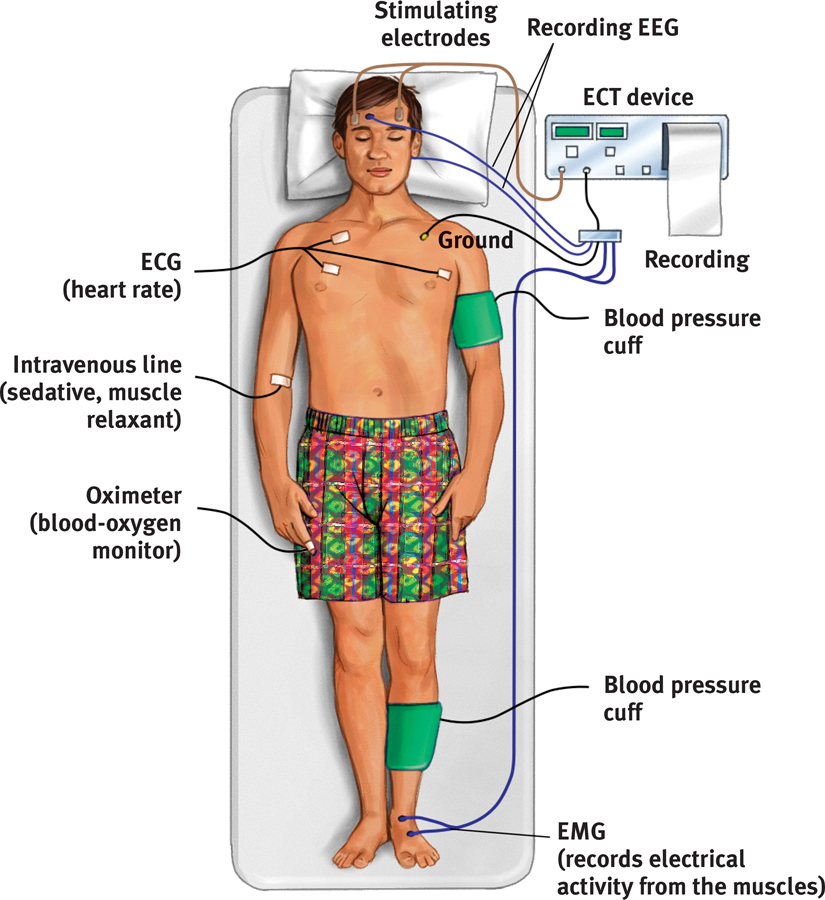

Electroconvulsive Therapy

A more controversial brain manipulation occurs through shock treatment, or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). When ECT was first introduced in 1938, the wide-

Figure 56.2

Figure 56.2Electroconvulsive therapy Although controversial, ECT is often an effective treatment for depression that does not respond to drug therapy. (“Electroconvulsive” is no longer accurate, because patients are now given a drug that prevents bodily convulsions.)

The medical use of electricity is an ancient practice. Physicians treated the Roman Emperor Claudius (10 B.C.E.–54 C.E.) for headaches by pressing electric eels to his temples.

How does ECT alleviate severe depression? After more than 70 years, no one knows for sure. One recipient likened ECT to the smallpox vaccine, which was saving lives before we knew how it worked. Others think of it as rebooting their cerebral computer. But what makes it therapeutic? Perhaps the shock-

“I used to … be unable to shake the dread even when I was feeling good, because I knew the bad feelings would return. ECT has wiped away that foreboding. It has given me a sense of control, of hope.”

Kitty Dukakis (2006)

ECT is now administered with briefer pulses, sometimes only to the brain’s right side and with less memory disruption (HMHL, 2007). Yet no matter how impressive the results, the idea of electrically shocking people still strikes many as barbaric, especially given our ignorance about why ECT works. Moreover, about 4 in 10 ECT-

Alternative Neurostimulation Therapies

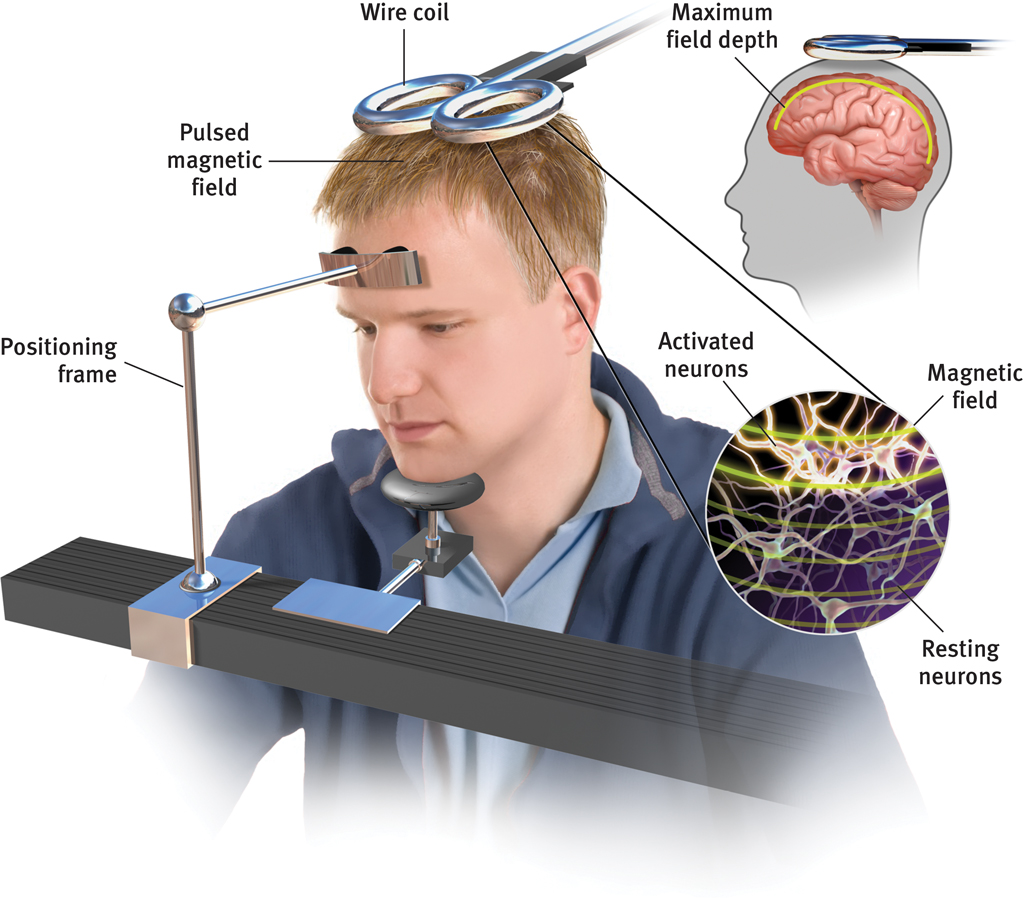

Two other neural stimulation techniques—

Magnetic StimulationDepressed moods sometimes improve when repeated pulses surge through a magnetic coil held close to a person’s skull (FIGURE 56.3). The painless procedure—

Figure 56.3

Figure 56.3Magnets for the mind Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) sends a painless magnetic field through the skull to the surface of the cortex. Pulses can be used to alter activity in various cortical areas.

A meta-analysis of 17 clinical experiments found that one other stimulation procedure alleviates depression: massage therapy (Hou et al., 2010).

Seven initial studies have found rTMS to be a “promising treatment,” with results comparable to antidepressants (Berlim et al., 2013). How it works is unclear. One possible explanation is that the stimulation energizes the brain’s left frontal lobe (Helmuth, 2001). Repeated stimulation may cause nerve cells to form new functioning circuits through the process of long-

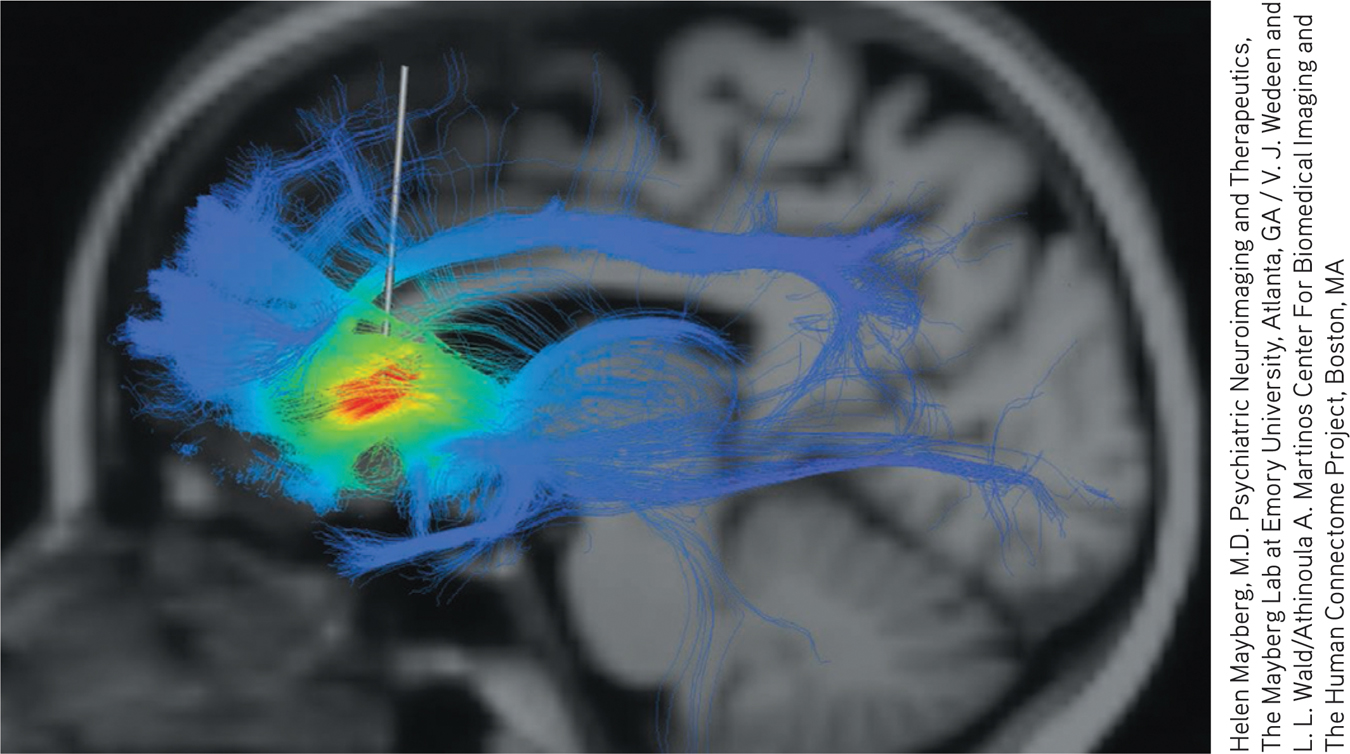

Deep-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Severe depression that has not responded to other therapy may be treated with __________ __________ , which can cause brain seizures and memory loss. More moderate neural stimulation techniques designed to help alleviate depression include__________ __________ magnetic stimulation , and __________-__________ stimulation.

electroconvulsive therapy (ECT ); repetitive transcranial; deep-