8.1 Defining Consciousness

8-1 What is the place of consciousness in psychology’s history?

At its beginning, psychology was “the description and explanation of states of consciousness” (Ladd, 1887). But during the first half of the twentieth century, the difficulty of scientifically studying consciousness led many psychologists—including those in the emerging school of behaviorism—to turn to direct observations of behavior. By the 1960s, psychology had nearly lost consciousness and was defining itself as “the science of behavior.” Consciousness was likened to a car’s speedometer: “It doesn’t make the car go, it just reflects what’s happening” (Seligman, 1991, p. 24).

“Psychology must discard all reference to consciousness.”

Behaviorist John B. Watson (1913)

After 1960, mental concepts reemerged. Neuroscience advances linked brain activity to sleeping, dreaming, and other mental states. Researchers began studying consciousness altered by hypnosis, drugs, and meditation. Psychologists of all persuasions were affirming the importance of cognition, or mental processes. Psychology was regaining consciousness.

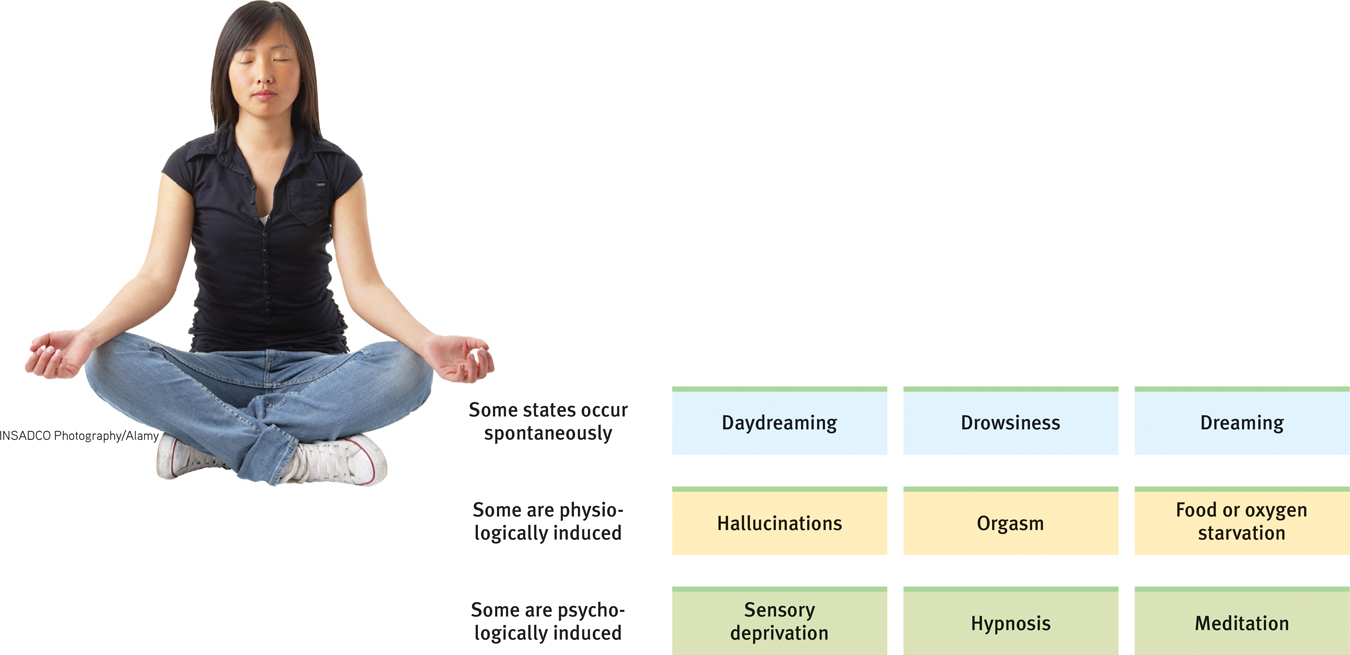

Most psychologists now define consciousness as our awareness of ourselves and our environment. This awareness allows us to assemble information from many sources as we reflect on our past and plan for our future. And it focuses our attention when we learn a complex concept or behavior. When learning to drive, we focus on the car and the traffic. With practice, driving becomes semiautomatic, freeing us to focus our attention on other things. Over time, we flit between different states of consciousness, including normal waking awareness and various altered states (FIGURE 8.1).

Figure 8.1

Figure 8.1Altered states of consciousness In addition to normal, waking awareness, consciousness comes to us in altered states, including daydreaming, drug-induced hallucinating, and meditating.

Today’s science explores the biology of consciousness. Evolutionary psychologists presume that consciousness offers a reproductive advantage (Barash, 2006; Murdik et al., 2011). Consciousness helps us cope with novel situations and act in our long-term interests, rather than merely seeking short-term pleasure and avoiding pain. Consciousness also promotes our survival by anticipating how we seem to others and helping us read their minds: “He looks really angry! I’d better run!”

Such explanations still leave us with the “hard problem”: How do brain cells jabbering to one another create our awareness of the taste of a taco, the idea of infinity, the feeling of fright? The question of how consciousness arises from the material brain is, for many scientists, one of life’s deepest mysteries.