8.3 Selective Attention

8-3 How does selective attention direct our perceptions?

Unconscious parallel processing is faster than sequential conscious processing, but both are essential. Parallel processing enables your mind to take care of routine business. Sequential processing is best for solving new problems, which requires our focused attention. Try this: If you are right-handed, move your right foot in a smooth counterclockwise circle and write the number 3 repeatedly with your right hand—at the same time. Try something equally difficult: Tap a steady three times with your left hand while tapping four times with your right hand. Both tasks require conscious attention, which can be in only one place at a time. If time is nature’s way of keeping everything from happening at once, then consciousness is nature’s way of keeping us from thinking and doing everything at once.

Through selective attention, your awareness focuses, like a flashlight beam, on a minute aspect of all that you experience. By one estimate, your five senses take in 11,000,000 bits of information per second, of which you consciously process about 40 (Wilson, 2002). Yet your mind’s unconscious track intuitively makes great use of the other 10,999,960 bits. Until reading this sentence, for example, you have been unaware of the chair pressing against your bottom or that your nose is in your line of vision. Now, suddenly, your attentional spotlight shifts. You feel the chair, your nose stubbornly intrudes on the words before you. While focusing on these words, you’ve also been blocking other parts of your environment from awareness, though your peripheral vision would let you see them easily. You can change that. As you stare at the X below, notice what surrounds these sentences.

X

A classic example of selective attention is the cocktail party effect—your ability to attend to only one voice among many. Let another voice speak your name and your cognitive radar, operating on your mind’s other track, will instantly bring that unattended voice into consciousness. This effect might have prevented an embarrassing and dangerous situation in 2009, when two Northwest Airlines pilots “lost track of time.” Focused on their laptops and in conversation, they ignored alarmed air traffic controllers’ attempts to reach them and overflew their Minneapolis destination by 150 miles. If only the controllers had known and spoken the pilots’ names.

Selective Attention and Accidents

Talk or text while driving, or attend to music selection or route planning, and your selective attention will shift back and forth between the road and its electronic competition. Indeed, it shifts more often than we realize. One study left people in a room free to surf the Internet and to control and watch a TV. On average, they guessed their attention switched 14.8 times during the 27.5 minute session. But they were not even close. Eye-tracking revealed eight times that many attentional switches—120 in all (Brasel & Gips, 2011). Such “rapid toggling” between activities is today’s great enemy of sustained, focused attention.

Visit LaunchPad to watch the thought-provoking Video—Automatic Skills: Disrupting a Pilot’s Performance.

Visit LaunchPad to watch the thought-provoking Video—Automatic Skills: Disrupting a Pilot’s Performance.

We pay a toll for switching attentional gears, especially when we shift to complex tasks, like noticing and avoiding cars around us. The toll is a slight and sometimes fatal delay in coping (Rubenstein et al., 2001). About 28 percent of traffic accidents occur when people are chatting or texting on cell phones (National Safety Council, 2010). One study tracked long-haul truck drivers for 18 months. The video cameras mounted in their cabs showed they were at 23 times greater risk of a collision while texting (VTTI, 2009). Mindful of such findings, the United States in 2010 banned truckers and bus drivers from texting while driving (Halsey, 2010).

It’s not just truck drivers who are at risk. One in four drivers admit to texting while driving (Pew, 2011). Multitasking comes at a cost: fMRI scans offer a biological account of how multitasking distracts from brain resources allocated to driving. In areas vital to driving, brain activity decreases an average 37 percent when a driver is attending to conversation (Just et al., 2008). To demonstrate the impossibility of simultaneous multitasking, try mentally multiplying 18 × 42 while passing a truck in busy traffic. (Actually, don’t try this.)

Even hands-free cell-phone talking is more distracting than chatting with passengers, who can see the driving demands, pause the conversation, and alert the driver to risks:

- University of Sydney researchers analyzed phone records for the moments before a car crash. Cell-phone users (even those with hands-free sets) were, like the average drunk driver, four times more at risk (McEvoy et al., 2005, 2007). Having a passenger increased risk only 1.6 times.

- When another research team installed cameras, GPS systems, and various sensors to the cars of teen drivers, they found that crashes and near-crashes increased sevenfold when dialing or reaching for a phone, and fourfold when sending or receiving a text message (Klauer et al., 2014).

- This risk difference also appeared when drivers were asked to pull off at a freeway rest stop 8 miles ahead. Of drivers conversing with a passenger, 88 percent did so. Of those talking on a cell phone, 50 percent drove on by (Strayer & Drews, 2007). And the increased risks are equal for handheld and hands-free phones, indicating that the distraction effect is mostly cognitive rather than visual (Strayer & Watson, 2012).

Most European countries and some American states now ban hand-held cell phones while driving (Rosenthal, 2009). Engineers are also devising ways to monitor drivers’ gaze and to direct their attention back to the road (Lee, 2009).

Selective Inattention

At the level of conscious awareness, we are “blind” to all but a tiny sliver of visual stimuli. Ulric Neisser (1979) and Robert Becklen and Daniel Cervone (1983) demonstrated this inattentional blindness dramatically by showing people a one-minute video in which images of three black-shirted men tossing a basketball were superimposed over the images of three white-shirted players. The viewers’ supposed task was to press a key every time a black-shirted player passed the ball. Most focused their attention so completely on the game that they failed to notice a young woman carrying an umbrella saunter across the screen midway through the video (FIGURE 8.5). Seeing a replay of the video, viewers were astonished to see her (Mack & Rock, 2000). This inattentional blindness is a by-product of what we are really good at: focusing attention on some part of our environment.

Figure 8.5

Figure 8.5Selective inattention Viewers who were attending to basketball tosses among the black-shirted players usually failed to notice the umbrella-toting woman sauntering across the screen (Neisser, 1979).

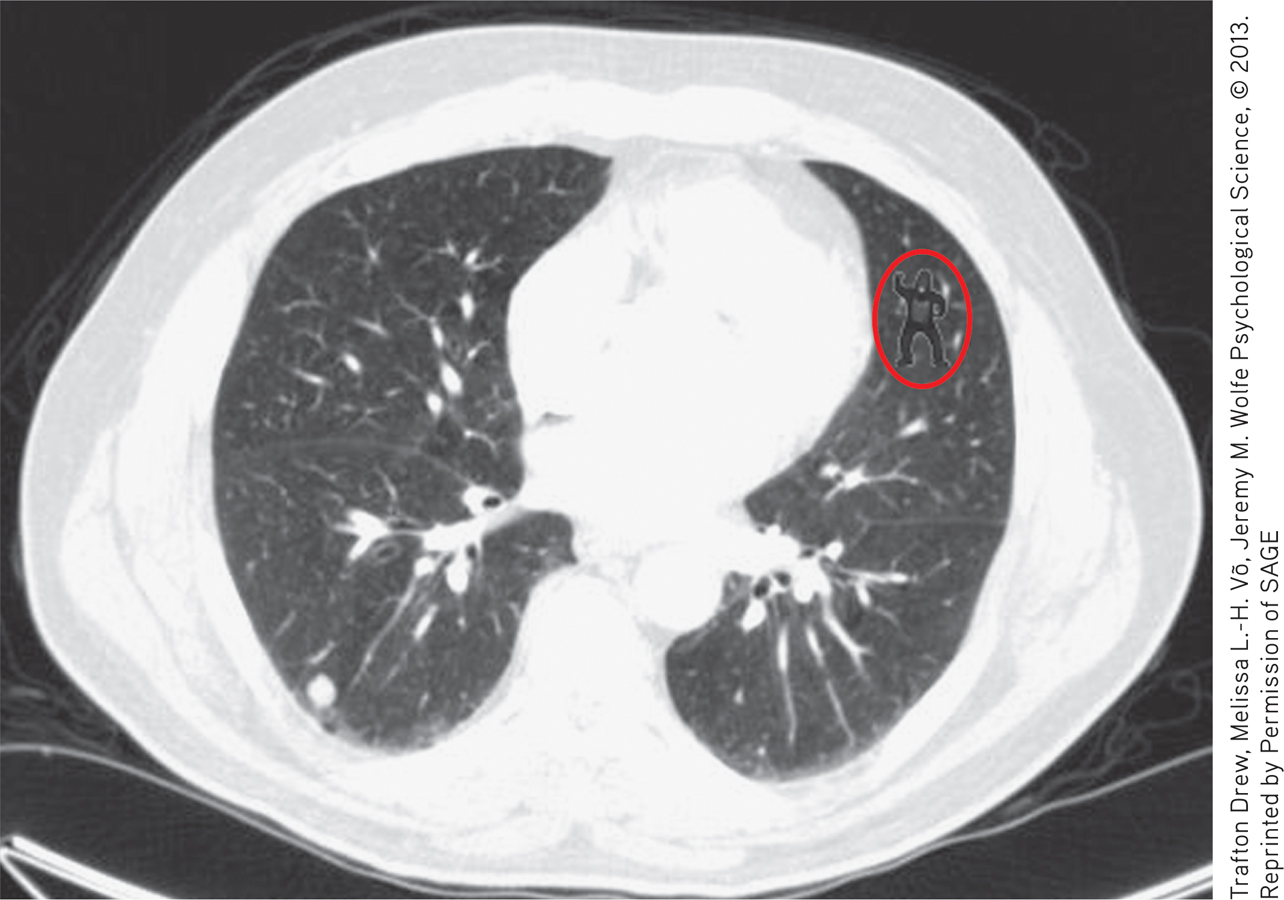

In a repeat of the experiment, smart-aleck researchers sent a gorilla-suited assistant through the swirl of players (Simons & Chabris, 1999). During its 5-to 9-second cameo appearance, the gorilla paused to thump its chest. Still, half the conscientious pass-counting viewers failed to see it. Psychologists have continued to have fun with invisible gorillas. One study of “inattentional deafness” delivered, separately to each ear, a recording of men talking and of women talking. When volunteers were assigned to pay attention to the women, 70 percent failed to hear one of the men saying, over and over for 19 seconds, “I’m a gorilla” (Dalton & Fraenkel, 2012). And when 24 radiologists were looking for cancer nodules in lung scans, 20 of them missed the gorilla superimposed in the upper right FIGURE 8.6—though, to their credit, they were able to see what they were looking for, the much tinier cancer tissue (Drew et al., 2013). The serious point to this psychological mischief: Attention is powerfully selective. Your conscious mind is in one place at a time.

Figure 8.6

Figure 8.6The invisible gorilla strikes again When exposed to the gorilla in the upper right several times, and even when looking at it, radiologists, searching for much tinier cancer nodules, usually failed to see it (Drew et al., 2013).

Given that most people miss someone in a gorilla suit while their attention is riveted elsewhere, imagine the fun that magicians can have by manipulating our selective attention. Misdirect people’s attention and they will miss the hand slipping into the pocket. “Every time you perform a magic trick, you’re engaging in experimental psychology,” says magician Teller, a master of mind-messing methods (2009). One Swedish psychologist was surprised in Stockholm by a woman exposing herself, only later realizing that he had been pickpocketed (Gallace, 2012).

“Has a generation of texters, surfers, and twitterers evolved the enviable ability to process multiple streams of novel information in parallel? Most cognitive psychologists doubt it.”

Steven Pinker, “Not at All,” 2010

In other experiments, people exhibited a form of inattentional blindness called change blindness. In laboratory experiments, viewers didn’t notice that, after a brief visual interruption, a big Coke bottle had disappeared, a railing had risen, or clothing color had changed (Chabris & Simons, 2010; Resnick et al., 1997). Focused on giving directions to a construction worker, two out of three people also failed to notice when he was replaced by another worker during a staged interruption (FIGURE 8.7). Out of sight, out of mind.

Figure 8.7

Figure 8.7Change blindness While a man (in red) provides directions to a construction worker, two experimenters rudely pass between them carrying a door. During this interruption, the original worker switches places with another person wearing different-colored clothing. Most people, focused on their direction giving, do not notice the switch (Simons & Levin, 1998).

With this forewarning, are you still vulnerable to change blindness? To find out, watch the 3-minute Video: Visual Attention, and prepare to be stunned.

With this forewarning, are you still vulnerable to change blindness? To find out, watch the 3-minute Video: Visual Attention, and prepare to be stunned.

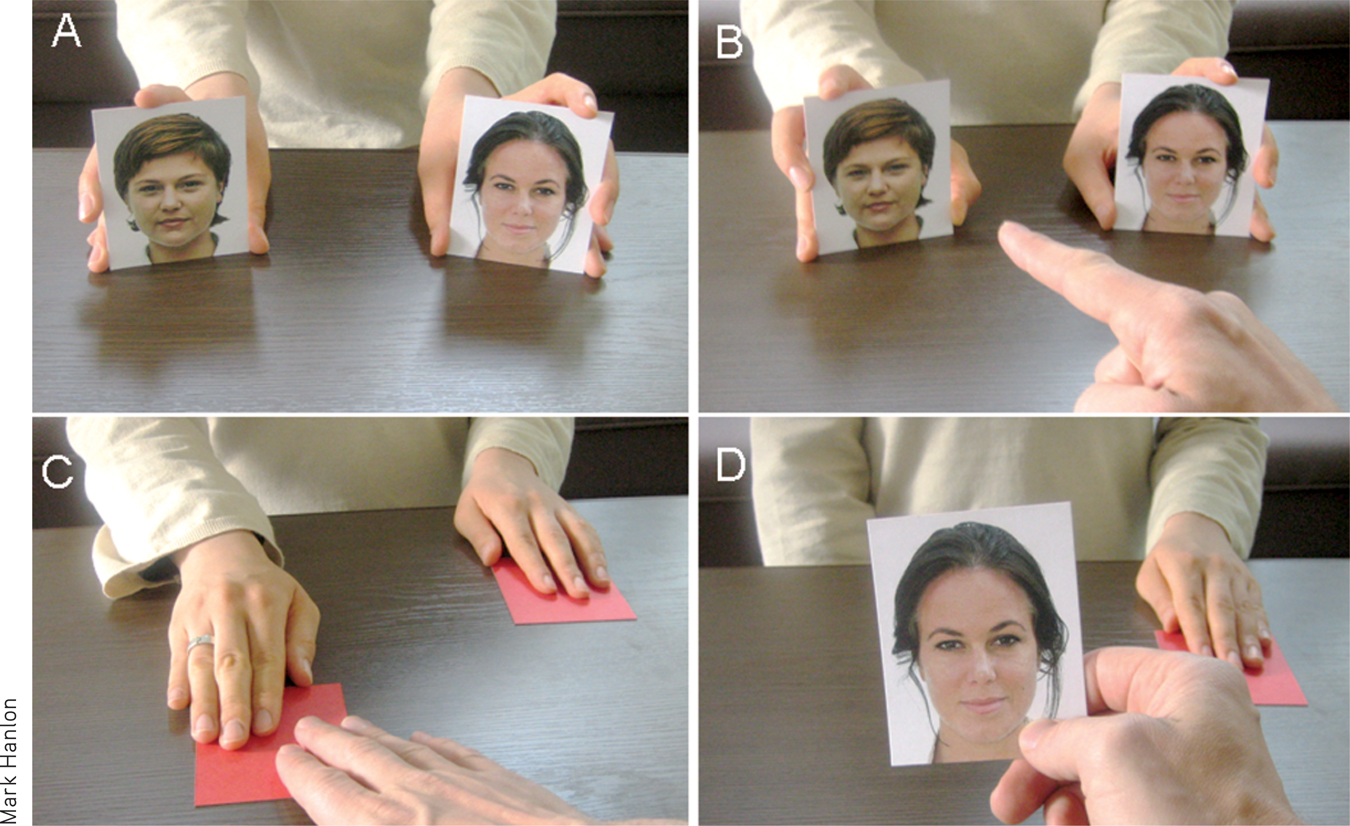

A Swedish research team discovered that people’s blindness extends to their own choices. Petter Johansson and his colleagues (2005, 2014) showed 120 volunteers two female faces and asked which face was more attractive. After putting both photos face down, they handed viewers the one chosen and invited them to explain why they preferred it. But on 3 of 15 occasions, the researchers used sleight-of-hand to switch the photos—showing viewers the face they had not chosen (FIGURE 8.8). People noticed the switch only 13 percent of the time, and readily explained why they preferred the face they had actually rejected. “I chose her because she smiled,” said one person (after picking the solemn-faced one). Asked later whether they would notice such a switch in a “hypothetical experiment,” 84 percent insisted they would.

Figure 8.8

Figure 8.8Choice blindness Pranksters Petter Johansson, Lars Hall, and others (2005) invited people to choose preferred faces. On occasion, they asked people to explain their preference for the unchosen photo. Most—failing to notice the switch—readily did so.

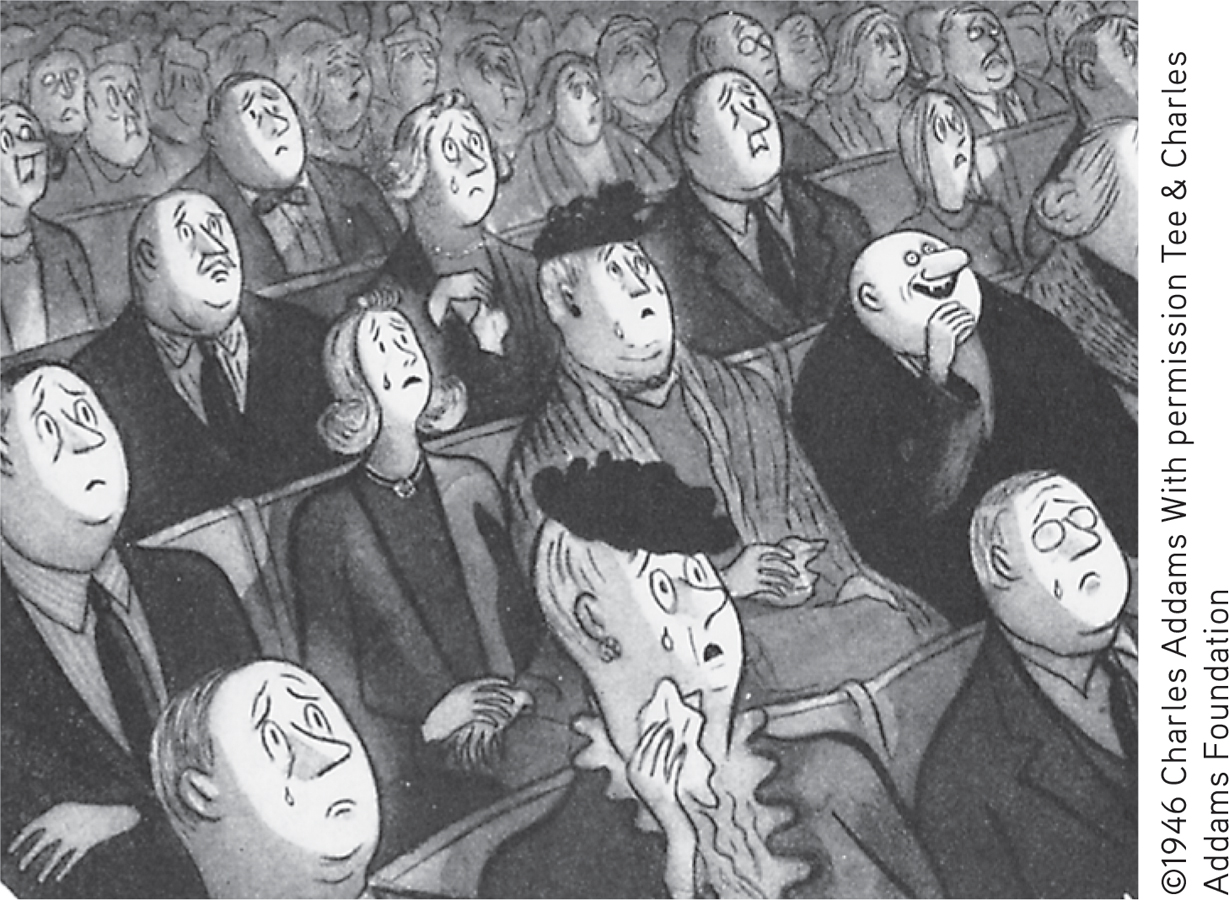

Change deafness can also occur. In one experiment, 40 percent of people focused on repeating a list of words that someone spoke failed to notice a change in the person speaking (Vitevitch, 2003). In two follow-up phone interview experiments, only 2 of 40 people noticed that the female interviewer changed after the third question (a change that was noticeable if people were forewarned of a possible interviewer change) (Fenn et al., 2011). Some stimuli, however, are so powerful, so strikingly distinct, that we experience popout, as with the only smiling face in FIGURE 8.9 We don’t choose to attend to these stimuli; they draw our eye and demand our attention. Likewise, when the female phone interviewer changed to a male interviewer, virtually everyone noticed.

Figure 8.9

Figure 8.9The pop out phenomenon

The dual-track mind is active even during sleep, as the next module reveals.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Explain three attentional principles that magicians may use to fool us.

Our selective attention allows us to focus on only a limited portion of our surroundings. Inattentional blindness explains why we don’t perceive some things when we are distracted by others. And change blindness happens when we fail to notice a relatively unimportant change in our environment. All these principles help magicians fool us, as they direct our attention elsewhere to perform their tricks.