16.2 Social Influence

SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY’S GREAT LESSON is the enormous power of social influence. This influence can be seen in our conformity, our compliance, and our group behavior. Suicides, bomb threats, airplane hijackings, and UFO sightings all have a curious tendency to come in clusters. On campus, jeans are the dress code; on New York’s Wall Street or London’s Bond Street, dress suits are the norm. When we know how to act, how to groom, how to talk, life functions smoothly. Armed with social influence principles, advertisers, fund-raisers, and campaign workers aim to sway our decisions to buy, to donate, to vote. Isolated with others who share their grievances, dissenters may gradually become rebels, and rebels may become terrorists. Let’s examine the pull of these social strings. How strong are they? How do they operate?

NOTE: This section has not yet been "DigFir'd": it currently contains the text exactly as it appears in Myers 9e, with only a few free-response questions in place.

16.2.1 Conformity and Obedience

3: What do experiments on conformity and compliance reveal about the power of social influence?

Behavior is contagious. Consider:

- A cluster of people stand gazing upward, and passersby pause to do likewise.

- Baristas and street musicians know to “seed” their tip containers with money to suggest that others have given.

- One person laughs, coughs, or yawns, and others in the group soon do the same. Chimpanzees, too, are more likely to yawn after observing another chimpanzee yawn (Anderson et al., 2004).

- “Sickness” can also be psychologically contagious. In the anxious 9/11 aftermath, more than two dozen elementary and middle schools had outbreaks of children reporting red rashes, sometimes causing parents to wonder whether biological terrorism was at work (Talbot, 2002). Some cases may have been stress-related, but mostly, health experts concluded, people were just noticing normal early acne, insect bites, eczema, and dry skin from overheated classrooms.

We are natural mimics—an effect Tanya Chartrand and John Bargh (1999) have called the chameleon effect. Unconsciously mimicking others’ expressions, postures, and voice tones helps us feel what they are feeling. This helps explain why we feel happier around happy people than around depressed ones, and why studies of groups of British nurses and accountants reveal mood linkage—sharing up and down moods (Totterdell et al., 1998). Just hearing someone reading a neutral text in either a happyor sad-sounding voice creates “mood contagion” in listeners (Neumann & Strack, 2000).

Chartrand and Bargh demonstrated the chameleon effect when they had students work in a room alongside a confederate working for the experimenter. Sometimes the confederates rubbed their face; on other occasions, they shook their foot. Sure enough, participants tended to rub their own face when with the face-rubbing person and shake their own foot when with the foot-shaking person. Such automatic mimicry is part of empathy. Empathic people yawn more after seeing others yawn (Morrison, 2007). And empathic, mimicking people are liked more. Those most eager to fit in with a group seem intuitively to know this, for they are especially prone to unconscious mimicry (Lakin & Chartrand, 2003).

Sometimes the effects of suggestibility are more serious. In the eight days following the 1999 shooting rampage at Colorado’s Columbine High School, every U.S. state except Vermont experienced threats of copycat violence. Pennsylvania alone recorded 60 such threats (Cooper, 1999). Sociologist David Phillips and his colleagues (1985, 1989) found that suicides, too, sometimes increase following a highly publicized suicide. In the wake of screen idol Marilyn Monroe’s suicide on August 6, 1962, for example, the number of suicides in the United States exceeded the usual August count by 200. Within a one-year period, one London psychiatric unit experienced 14 patient suicides (Joiner, 1999). In the days after Saddam Hussein’s widely publicized execution in Iraq, there were case of boys in Turkey, Pakistan, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, and the United States who hung themselves, apparently accidently, after slipping nooses around their own heads (AP, 2007).

What causes suicide clusters? Do people act similarly because of their influence on one another? Or because they are simultaneously exposed to the same events and conditions? Seeking answers, social psychologists have conducted experiments on group pressure and conformity.

16.2.2 Group Pressure and Conformity

Suggestibility is a subtle type of conformity—adjusting our behavior or thinking toward some group standard. To study conformity, Solomon Asch (1955) devised a simple test. As a participant in what you believe is a study of visual perception, you arrive at the experiment location in time to take a seat at a table where five people are already seated. The experimenter asks which of three comparison lines is identical to a standard line (Figure 16.2). You see clearly that the answer is Line 2 and await your turn to say so after the others. Your boredom with this experiment begins to show when the next set of lines proves equally easy.

Now comes the third trial, and the correct answer seems just as clear-cut, but the first person gives what strikes you as a wrong answer: “Line 3.” When the second person and then the third and fourth give the same wrong answer, you sit up straight and squint. When the fifth person agrees with the first four, you feel your heart begin to pound. The experimenter then looks to you for your answer. Torn between the unanimity of your five fellow respondents and the evidence of your own eyes, you feel tense and much less sure of yourself than you were moments ago. You hesitate before answering, wondering whether you should suffer the discomfort of being the oddball. What answer do you give?

In the experiments conducted by Asch and others after him, thousands of college students have experienced this conflict. Answering such questions alone, they erred less than 1 percent of the time. But the odds were quite different when several others—confederates working for the experimenter—answered incorrectly. Although most people told the truth even when others did not, Asch nevertheless was disturbed by his result: More than one-third of the time, these “intelligent and well-meaning” college-student participants were then “willing to call white black” by going along with the group.

16.2.3 Conditions That Strengthen Conformity

Asch’s procedure became the model for later investigations. Although experiments have not always found so much conformity, they do reveal that conformity increases when

- one is made to feel incompetent or insecure.

- the group has at least three people.

- the group is unanimous. (The dissent of just one other person greatly increases social courage.)

- one admires the group’s status and attractiveness.

- one has made no prior commitment to any response.

- others in the group observe one’s behavior.

- one’s culture strongly encourages respect for social standards.

Thus, we might predict the behavior of Austin, an enthusiastic but insecure new fraternity member: Noting that the 40 other members appear unanimous in their plans for a fund-raiser, Austin is unlikely to voice his dissent.

16.2.4 Reasons for Conforming

“Have you ever noticed how one example—good or bad—can prompt others to follow? How one illegally parked car can give permission for others to do likewise? How one racial joke can fuel another?”

Marian Wright Edelman, The Measure of Our Success, 1992

Fish swim in schools. Birds fly in flocks. And humans, too, tend to go with their group, to think what it thinks and do what it does. Researchers have seen this in college residence halls, where over time students’ attitudes become more similar to those living near them (Cullum & Harton, 2007). But why? Why do we clap when others clap, eat as others eat, believe what others believe, even see what others see? Frequently, it is to avoid rejection or to gain social approval. In such cases, we are responding to what social psychologists call normative social influence. We are sensitive to social norms—understood rules for accepted and expected behavior—because the price we pay for being different may be severe.

Respecting norms is not the only reason we conform: Groups may provide valuable information, and only an uncommonly stubborn person will never listen to others. When we accept others’ opinions about reality, we are responding to informational social influence. “Those who never retract their opinions love themselves more than they love truth,” observed the eighteenth-century French essayist, Joseph Joubert. As Rebecca Denton demonstrated in 2004, sometimes it pays to assume others are right and to follow their lead. Denton set a record for the furthest distance driven on the wrong side of a British divided highway—30 miles, with only one minor sideswipe, before the motorway ran out and police were able to puncture her tires. Denton later explained that she thought the hundreds of other drivers coming at her were all on the wrong side of the road (Woolcock, 2004).

Robert Baron and his colleagues (1996) cleverly demonstrated our openness to informational influence on tough, important judgments. They modernized the Asch experiment by showing University of Iowa students a slide of a stimulus person, followed by a slide of a four-person lineup (Figure 16.3). Their experiment made the task either easy (viewing the lineup for five seconds) or difficult (viewing the lineup for but half a second). It also led them to think their judgments were either unimportant (just a preliminary test of some eyewitness identification procedures) or important (establishing norms for an actual police procedure, with a $20 award to the most accurate participants). When the accuracy of their judgments seemed important, people rarely conformed when the task was easy, but they conformed half the time when the task was difficult. If we are unsure of what is right, and if being right matters, we are receptive to others’ opinions.

Question 16.9

Under what conditions are people most likely to conform?

Solomon Asch's (1955) studies revealed specific factors that increase the chances we will conform to a group decision: feelings of insecurity/incompetence, a group of at least three people, the group is unanimous in their opinion/answer, we perceive that others in the group have a higher status, we haven't already committed to a response, we know that others in the group can observe our behavior, and our culture encourages respect for social standards.

16.2.5 Obedience

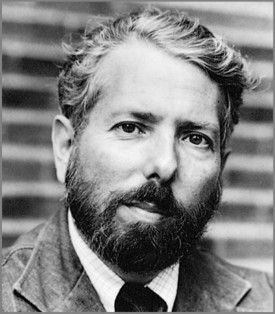

Social psychologist Stanley Milgram (1963, 1974), a student of Solomon Asch, knew that people often comply with social pressures. But how would they respond to outright commands? To find out, he undertook what have become social psychology’s most famous and controversial experiments. Imagine yourself as one of the nearly 1000 participants in Milgram’s 20 experiments.

Responding to an advertisement, you come to Yale University’s psychology department to participate in an experiment. Professor Milgram’s assistant explains that the study concerns the effect of punishment on learning. You and another person draw slips from a hat to see who will be the “teacher” (which your slip says) and who will be the “learner.” The learner is then led to an adjoining room and strapped into a chair that is wired through the wall to an electric shock machine. You sit in front of the machine, which has switches labeled with voltages. Your task: to teach and then test the learner on a list of word pairs. You are to punish the learner for wrong answers by delivering brief electric shocks, beginning with a switch labeled “15 Volts—Slight Shock.” After each of the learner’s errors, you are to move up to the next higher voltage. With each flick of a switch, lights flash, relay switches click on, and an electric buzzing fills the air.

Complying with the experimenter’s instructions, you hear the learner grunt when you flick the third, fourth, and fifth switches. After you activate the eighth switch (labeled “120 Volts—Moderate Shock”), the learner shouts that the shocks are painful. After the tenth switch (“150 Volts—Strong Shock”), he cries, “Get me out of here! I won’t be in the experiment anymore! I refuse to go on!” Hearing these pleas, you draw back. But the experimenter prods you: “Please continue—the experiment requires that you continue.” If you still resist, he insists, “It is absolutely essential that you continue,” or “You have no other choice, you must go on.”

Obeying, you hear the learner’s protests escalate to shrieks of agony as you continue to raise the shock level with each succeeding error. After the 330-volt level, the learner refuses to answer and falls silent. Still, the experimenter pushes you toward the final, 450-volt switch, ordering you to ask the questions and, if no correct answer is given, to administer the next shock level.

How far do you think you would follow the experimenter’s commands? In a survey Milgram conducted before the experiment, most people declared they would stop playing such a sadistic-seeming role soon after the learner first indicated pain and certainly before he shrieked in agony. This also was the prediction made by each of 40 psychiatrists Milgram asked to guess the outcome. When Milgram actually conducted the experiment with men aged 20 to 50, he was astonished to find that 63 percent complied fully—right up to the last switch. Ten later studies that included women found women’s compliance rates were similar to men’s (Blass, 1999).

Did the teachers figure out the hoax—that no shock was being delivered? Did they correctly guess the learner was a confederate who only pretended to feel the shocks? Did they realize the experiment was really testing their willingness to comply with commands to inflict punishment? No. The teachers typically displayed genuine distress:They perspired, trembled, laughed nervously, and bit their lips. In a recent virtual reality recreation of these experiments, participants responded much as did Milgram’s participants, including perspiration and racing heart, when shocking a virtual woman on a screen in front of them (Slater et al., 2006).

Milgram’s use of deception and stress triggered a debate over his research ethics. In his own defense, Milgram pointed out that, after the participants learned of the deception and actual research purposes, virtually none regretted taking part (though perhaps by then the participants had reduced their dissonance). When 40 of the teachers who had agonized most were later interviewed by a psychiatrist, none appeared to be suffering emotional aftereffects. All in all, said Milgram, the experiments provoked less enduring stress than university students experience when facing and failing big exams (Blass, 1996).

Wondering whether the participants obeyed because the learners’ protests were not convincing, Milgram repeated the experiment with 40 new teachers. This time his confederate mentioned a “slight heart condition” while being strapped into the chair, and then he complained and screamed more intensely as the shocks became more punishing. Still, 65 percent of the new teachers complied fully (Figure 16.4).

16.2.6 Obedience (continued)

In later experiments, Milgram discovered that subtle details of a situation powerfully influence people. When he varied the social conditions, the proportion of fully compliant participants varied from 0 to 93 percent. Obedience was highest when

- the person giving the orders was close at hand and was perceived to be a legitimate authority figure. (Such was the case in 2005 when Temple University’s basketball coach sent a 250-pound bench player, Nehemiah Ingram, into a game with instructions to commit “hard fouls.” Following orders, Ingram fouled out in four minutes after breaking an opposing player’s right arm.)

- the authority figure was supported by a prestigious institution. Compliance was somewhat lower when Milgram dissociated his experiments from Yale University.

- the victim was depersonalized or at a distance, even in another room. (Similarly, in combat with an enemy they can see, many soldiers either do not fire their rifles or do not aim them properly. Such refusals to kill are rare among those who operate more distant artillery or aircraft weapons [Padgett, 1989].)

- there were no role models for defiance; that is, no other participants were seen disobeying the experimenter.

The power of legitimate, close-at-hand authorities is dramatically apparent in stories of those who complied with orders to carry out the Holocaust atrocities, and those who didn’t. Obedience alone does not explain the Holocaust; anti-Semitic ideology produced eager killers as well (Mastroianni, 2002). But obedience was a factor. In the summer of 1942 nearly 500 middle-aged German reserve police officers were dispatched to German-occupied Jozefow, Poland. On July 13, the group’s visibly upset commander informed his recruits, mostly family men, that they had been ordered to round up the village’s Jews, who were said to be aiding the enemy. Able-bodied men were to be sent to work camps, and all the rest were to be shot on the spot. Given a chance to refuse participation in the executions, only about a dozen immediately did so. Within 17 hours, the remaining 485 officers killed 1500 helpless women, children, and elderly by shooting them in the back of the head as they lay face down. Hearing the pleas of the victims, and seeing the gruesome results, some 20 percent of the officers did eventually dissent, managing either to miss their victims or to wander away and hide until the slaughter was over (Browning, 1992). But in real life, as in Milgram’s experiments, the disobedient were the minority.

Another story was being played out in the French village of Le Chambon, where French Jews destined for deportation to Germany were being sheltered by villagers who openly defied orders to cooperate with the “New Order.” The villagers’ ancestors had themselves been persecuted and their pastors had been teaching them to “resist whenever our adversaries will demand of us obedience contrary to the orders of the Gospel” (Rochat, 1993). Ordered by police to give a list of sheltered Jews, the head pastor modeled defiance:“I don’t know of Jews, I only know of human beings.” Without realizing how long and terrible the war would be, or how much punishment and poverty they would suffer, the resisters made an initial commitment to resist. Supported by their beliefs, their role models, their interactions with one another, and their own initial acts, they remained defiant to the war’s end.

16.2.7 Lessons From the Conformity and Obedience Studies

What do the Asch and Milgram experiments teach us about ourselves? How does judging the length of a line or flicking a shock switch relate to everyday social behavior? Recall from Chapter 1 that psychological experiments aim not to re-create the literal behaviors of everyday life but to capture and explore the underlying processes that shape those behaviors. Asch and Milgram devised experiments in which the participants had to choose between adhering to their own standards and being responsive to others, a dilemma we all face frequently.

In Milgram’s experiments, participants were also torn between what they should respond to—the pleas of the victim or the orders of the experimenter. Their moral sense warned them not to harm another, yet it also prompted them to obey the experimenter and to be a good research participant. With kindness and obedience on a collision course, obedience usually won.

“I was only following orders.”

Adolf Eichmann, Director of Nazi deportation of Jews to concentration camps

Such experiments demonstrate that strong social influences can make people conform to falsehoods or capitulate to cruelty. “The most fundamental lesson of our study,” Milgram noted, is that “ordinary people, simply doing their jobs, and without any particular hostility on their part, can become agents in a terrible destructive process” (1974, p. 6). Milgram did not entrap his teachers by asking them first to zap learners with enough electricity to make their hair stand on end. Rather, he exploited the foot-in-the-door effect, beginning with a little tickle of electricity and escalating step by step. In the minds of those throwing the switches, the small action became justified, making the next act tolerable. In Jozefow, in Le Chambon, and in Milgram’s experiments, those who resisted usually did so early. After the first acts of compliance or resistance, attitudes began to follow and justify behavior.

“The normal reaction to an abnormal situation is abnormal behavior.”

James Waller, Becoming Evil: How Ordinary People Commit Genocide and Mass Killing, 2007

So it happens when people succumb, gradually, to evil. In any society, great evils sometimes grow out of people’s compliance with lesser evils. The Nazi leaders suspected that most German civil servants would resist shooting or gassing Jews directly, but they found them surprisingly willing to handle the paperwork of the Holocaust (Silver & Geller, 1978). Likewise, when Milgram asked 40 men to administer the learning test while someone else did the shocking, 93 percent complied. Contrary to images of devilish villains, cruelty does not require monstrous characters; all it takes is ordinary people corrupted by an evil situation—ordinary soldiers who follow orders to torture prisoners, ordinary students who follow orders to haze initiates into their group, ordinary employees who follow orders to produce and market harmful products. Before leading the 9/11 attacks, Mohammed Atta reportedly was a sane, rational person who had been a “good boy” and an excellent student from a close-knit family—not someone who fits our image of a barbaric monster.

16.2.8 Group Influence

How do groups affect our behavior? To find out, social psychologists study the various influences that operate in the simplest of groups—one person in the presence of another—and those that operate in more complex groups, such as families, teams, and committees.

16.2.9 Individual Behavior in the Presence of Others

4: How is our behavior affected by the presence of others or by being part of a group?

Appropriately, social psychology’s first experiments focused on the simplest of all questions about social behavior: How are we influenced by people watching us or joining us in various activities?

16.2.10 Social Facilitation

Having noticed that cyclists’ racing times were faster when they competed against each other than when they competed with a clock, Norman Triplett (1898) hypothesized that the presence of others boosts performance. To test his hypothesis, Triplett had adolescents wind a fishing reel as rapidly as possible. He discovered that they wound the reel faster in the presence of someone doing the same thing. This phenomenon of stronger performance in others’ presence is called social facilitation. For example, after a light turns green, drivers take about 15 percent less time to travel the first 100 yards when another car is beside them at the intersection than when they are alone (Towler, 1986).

But on tougher tasks (learning nonsense syllables or solving complex multiplication problems), people perform less well when observers or others working on the same task are present. Further studies revealed why the presence of others sometimes helps and sometimes hinders performance (Guerin, 1986; Zajonc, 1965). When others observe us, we become aroused. This arousal strengthens the most likely response—the correct one on an easy task, an incorrect one on a difficult task. Thus, when we are being observed, we perform well-learned tasks more quickly and accurately, and unmastered tasks less quickly and accurately.

James Michaels and his associates (1982) found that expert pool players who made 71 percent of their shots when alone made 80 percent when four people came to watch them. Poor shooters, who made 36 percent of their shots when alone, made only 25 percent when watched. The energizing effect of an enthusiastic audience probably contributes to the home advantage enjoyed by various sports teams. Studies of more than 80,000 college and professional athletic events in Canada, the United States, and England reveal that home teams win about 6 in 10 games (somewhat fewer for baseball and football, somewhat more for basketball and soccer—see Table 16.1).

The point to remember: What you do well, you are likely to do even better in front of an audience, especially a friendly audience; what you normally find difficult may seem all but impossible when you are being watched.

Social facilitation also helps explain a funny effect of crowding: Comedy routines that are mildly amusing to people in an uncrowded room seem funnier in a densely packed room (Aiello et al., 1983; Freedman & Perlick, 1979). As comedians and actors know, a “good house” is a full one. The arousal triggered by crowding amplifies other reactions, too. If sitting close to one another, participants in experiments like a friendly person even more, an unfriendly person even less (Schiffenbauer & Schiavo, 1976; Storms & Thomas, 1977). The practical lesson: If choosing a room for a class or setting up chairs for a gathering, have barely enough seating.

16.2.11 Social Loafing

Social facilitation experiments test the effect of others’ presence on performance on an individual task, such as shooting pool. But what happens to performance when people perform the task as a group? In a team tug-of-war, for example, do you suppose your effort would be more than, less than, or the same as the effort you would exert in a one-on-one tug-of-war? To find out, Alan Ingham and his fellow researchers (1974) asked blindfolded University of Massachusetts students to “pull as hard as you can” on a rope. When Ingham fooled the students into believing three others were also pulling behind them, they exerted only 82 percent as much effort as when they knew they were pulling alone.

Bibb Latané (1981; Jackson & Williams, 1988) describe this diminished effort as social loafing. In 78 experiments conducted in the United States, India, Thailand, Japan, China, and Taiwan, social loafing occurred on various tasks, though it was especially common among men in individualistic cultures (Karau & Williams, 1993). In one of Latané’s experiments, blindfolded people seated in a group clapped or shouted as loud as they could while listening through headphones to the sound of loud clapping or shouting. When told they were doing it with the others, the participants produced about one-third less noise than when they thought their individual efforts were identifiable.

Why this social loafing? First, people acting as part of a group feel less accountable and therefore worry less about what others think. Second, they may view their contribution as dispensable (Harkins & Szymanski, 1989; Kerr & Bruun, 1983). As many leaders of organizations know—and as you have perhaps observed on student group assignments—if group members share equally in the benefits regardless of how much they contribute, some may slack off. Unless highly motivated and identified with their group, they may free-ride on the other group members’ efforts.

Question 16.10

When is social facilitation most likely to occur? Social loafing?

Social facilitation occurs when we perform tasks that we are skilled at in front of others. The extra excitement (arousal) provided by the presence of an audience can enhance our performance on tasks that are easy for us or that we have practiced extensively. This arousal will actually hurt our performance on tasks that we are not skilled at. Social loafing occurs when we are performing a task with a group and the knowledge that others are performing the task too causes us to not try as hard.

16.2.12 Deindividuation

So, the presence of others can arouse people (as in the social facilitation experiments) or can diminish their feelings of responsibility (as in the social loafing experiments). But sometimes the presence of others both arouses people anddiminishes their sense of responsibility. The result can be uninhibited behavior ranging from a food fight in the dining hall or screaming at a basketball referee to vandalism or rioting. Abandoning normal restraints to the power of the group is termed deindividuation. To be deindividuated is to be less self-conscious and less restrained when in a group situation.

Deindividuation often occurs when group participation makes people feel aroused and anonymous. In one experiment, New York University women dressed in depersonalizing Ku Klux Klan–style hoods delivered twice as much electric shock to a victim as did identifiable women (Zimbardo, 1970). (As in all such experiments, the “victim” did not actually receive the shocks.) Similarly, tribal warriors who depersonalize themselves with face paints or masks are more likely than those with exposed faces to kill, torture, or mutilate captured enemies (Watson, 1973). Whether in a mob, at a rock concert, at a ballgame, or at worship, to lose self-consciousness (to become deindividuated) is to become more responsive to the group experience.

16.2.13 Effects of Group Interaction

5: What are group polarization and groupthink?

We have examined the conditions under which being in the presence of others can

- motivate people to exert themselves or tempt them to free-ride on the efforts of others.

- make easy tasks easier and difficult tasks harder.

- enhance humor or fuel mob violence.

Research shows that interacting with others can similarly have both bad and good effects.

16.2.14 Group Polarization

Educational researchers have noted that, over time, initial differences between groups of college students tend to grow. If the first-year students at College X tend to be more intellectually oriented than those at College Y, that difference will probably be amplified by the time they are seniors. And if the political conservatism of students who join fraternities and sororities is greater than that of students who do not, the gap in the political attitudes of the two groups will probably widen as they progress through college (Wilson et al., 1975). Similarly, notes Eleanor Maccoby (2002) from her decades of observing gender development, girls talk more intimately than boys do and play and fantasize less aggressively—and these gender differences widen over time as they interact mostly with their own gender.

This enhancement of a group’s prevailing tendencies—called group polarization—occurs when people within a group discuss an idea that most of them either favor or oppose. Group polarization can have beneficial results, as when it amplifies a sought-after spiritual awareness or reinforces the resolve of those in a self-help group, or strengthens feelings of tolerance in a low-prejudice group. But it can also have dire consequences. George Bishop and I discovered that when high-prejudice students discussed racial issues, they became more prejudiced (Figure 16.5). (Low-prejudice students became even more accepting.) The experiment’s ideological separation and polarization finds a seeming parallel in the growing polarization of American politics. The percentage of landslide counties—voting 60 percent or more for one presidential candidate—increased from 26 percent in 1976 to 48 percent in 2004 (Bishop, 2004). More and more, people are living near and learning from others who think as they do. One experiment brought together small groups of citizens in liberal Boulder, Colorado, and other groups down in conservative Colorado Springs, to discuss global climate change, affirmative action, and same-sex unions. Although the discussions increased agreement within groups, those in Boulder generally moved further left and those in Colorado Springs moved further right (Schkade et al., 2006). Thus ideological separation + deliberation = polarization between groups.

The polarizing effect of interaction among the like-minded applies also to suicide terrorists. After analyzing terrorist organizations around the world, psychologists Clark McCauley and Mary Segal (1987; McCauley, 2002) noted that the terrorist mentality does not erupt suddenly. Rather, it usually arises among people who get together because of a grievance and then become more and more extreme as they interact in isolation from any moderating influences. Increasingly, group members (who may be isolated with other “brothers” and “sisters” in camps) categorize the world as “us” against “them” (Moghaddam, 2005; Qirko, 2004). Suicide terrorism is virtually never done on a personal whim, reports researcher Ariel Merari (2002). The like-minded echo chamber will continue to polarize people, speculates the 2006 U.S. National Intelligence estimate: “We assess that the operational threat from self-radicalized cells will grow.”

The Internet provides a medium for group polarization. Its tens of thousands of virtual groups enable bereaved parents, peacemakers, and teachers to find solace and support from kindred spirits. But the Internet also enables people who share interests in government conspiracy, extraterrestrial visitors, White supremacy, or citizen militias to find one another and to find support for their shared suspicions (McKenna & Bargh, 1998).

16.2.15 Groupthink

“One’s impulse to blow the whistle on this nonsense was simply undone by the circumstances of the discussion.”

Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., A Thousand Days, 1965

Does group interaction ever distort important decisions? Social psychologist Irving Janis began to think so as he read historian Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr.’s account of how President John F. Kennedy and his advisers blundered into an ill-fated plan to invade Cuba with 1400 CIA-trained Cuban exiles. When the invaders were easily captured and soon linked to the U.S. government, Kennedy wondered in hindsight, “How could we have been so stupid?”

To find out, Janis (1982) studied the decision-making procedures that led to the fiasco. He discovered that the soaring morale of the recently elected president and his advisers fostered undue confidence in the plan. To preserve the good group feeling, any dissenting views were suppressed or self-censored, especially after President Kennedy voiced his enthusiasm for the scheme. Since no one spoke strongly against the idea, everyone assumed consensus support. To describe this harmonious but unrealistic group thinking, Janis coined the term groupthink.

Janis and others then examined other historical fiascos—the failure to anticipate the 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the escalation of the Vietnam War, the U.S. Watergate cover-up, the Chernobyl nuclear reactor accident (Reason, 1987), and the U.S. space shuttle Challenger explosion (Esser & Lindoerfer, 1989). They discovered that in these cases, too, groupthink was fed by overconfidence, conformity, self-justification, and group polarization.

“Truth springs from argument among friends.”

Philosopher David Hume, 1711–1776

Groupthink surfaced again, reported the bipartisan U.S. Senate Intelligence Committee (2004), when “personnel involved in the Iraq WMD issue demonstrated several aspects of groupthink: examining few alternatives, selective gathering of information, pressure to conform within the group or withhold criticism, and collective rationalization.” This groupthink led analysts to “interpret ambiguous evidence as conclusively indicative of a WMD program as well as ignore or minimize evidence that Iraq did not have [WMD] programs.”

“If you have an apple and I have an apple and we exchange apples then you and I will still each have one apple. But if you have an idea and I have an idea and we exchange these ideas, then each of us will have two ideas.”

Attributed to dramatist George Bernard Shaw, 1856–1950

Despite such fiascos and tragedies, two heads are better than one in solving some types of problems. Knowing this, Janis also studied instances in which U.S. presidents and their advisers collectively made good decisions, such as when the Truman administration formulated the Marshall Plan, which offered assistance to Europe after World War II, and when the Kennedy administration worked to keep the Soviets from installing missiles in Cuba. In such instances—and in the business world, too, Janis believed—groupthink is prevented when a leader welcomes various opinions, invites experts’ critiques of developing plans, and assigns people to identify possible problems. Just as the suppression of dissent bends a group toward bad decisions, so open debate often shapes good ones. This is especially so with diverse groups, whose varied perspectives enable creative or superior outcomes (Nemeth & Ormiston, 2007; Page, 2007). None of us is as smart as all of us.

Question 16.11

What's the difference between group polarization and groupthink?

Group polarization and groupthink both occur in group decision making situations, but they refer to different kinds of group discussion outcomes. Group polarization occurs when a group of people who already agree about an issue talk about this issue, and after the discussion, group members feel more strongly about their shared opinions and attitudes than they did before the discussion. Groupthink occurs when a group discussion influences the group to make a poor decision. This can occur when members of the group are very focused on group harmony and are reluctant to contradict other members of the group. This lack of contrary voices can lead the group to make unrealistic or unwise decisions.

16.2.16 The Power of Individuals

6: How much power do we have as individuals? Can a minority sway a majority?

In affirming the power of social influence, we must not overlook our power as individuals.Social control (the power of the situation) and personal control (the power of the individual) interact. People aren’t billiard balls. When feeling pressured, we may react by doing the opposite of what is expected, thereby reasserting our sense of freedom (Brehm & Brehm, 1981).

Three individual soldiers asserted their personal control at the Abu Ghraib prison (O’Connor, 2004). Lt. David Sutton put an end to one incident, which he reported to his commanders. Navy dog-handler William Kimbro refused pressure to participate in improper interrogations using his attack dogs. Specialist Joseph Darby brought visual images of the horrors into the light of day, providing incontestable evidence of the atrocities. Each risked ridicule or even court-martial for not following orders.

As these three soldiers discovered, committed individuals can sway the majority and make social history. Were this not so, communism would have remained an obscure theory, Christianity would be a small Middle Eastern sect, and Rosa Parks’ refusal to sit at the back of the bus would not have ignited the U.S. civil rights movement. Technological history, too, is often made by innovative minorities who overcome the majority’s resistance to change. To many, the railroad was a nonsensical idea; some farmers even feared that train noise would prevent hens from laying eggs. People derided Robert Fulton’s steamboat as “Fulton’s Folly.” As Fulton later said, “Never did a single encouraging remark, a bright hope, a warm wish, cross my path.” Much the same reaction greeted the printing press, the telegraph, the incandescent lamp, and the typewriter (Cantril & Bumstead, 1960).

European social psychologists have sought to better understand minority influence—the power of one or two individuals to sway majorities (Moscovici, 1985). They investigated groups in which one or two individuals consistently expressed a controversial attitude or an unusual perceptual judgment. They repeatedly found that a minority that unswervingly holds to its position is far more successful in swaying the majority than is a minority that waffles. Holding consistently to a minority opinion will not make you popular, but it may make you influential. This is especially so if your self-confidence stimulates others to consider why you react as you do. Although people often follow the majority view publicly, they may privately develop sympathy for the minority view. Even when a minority’s influence is not yet visible, it may be persuading some members of the majority to rethink their views (Wood et al., 1994). The powers of social influence are enormous, but so are the powers of the committed individual.