Chapter 1

An Introduction to Statistics and Research Design

1

The Two Branches of Statistics

- Descriptive Statistics

- Inferential Statistics

- Distinguishing Between a Sample and a Population

How to Transform Observations into Variables

- Discrete Observations

- Continuous Observations

Variables and Research

- Independent, Dependent, and Confounding Variables

- Reliability and Validity

Introduction to Hypothesis Testing

- Conducting Experiments to Control for Confounding Variables

- Between-

Groups Design versus Within- Groups Design - Correlational Research

Next Steps: Outlier Analysis

BEFORE YOU GO ON

- You should be familiar with basic mathematics (see Reference for Basic Mathematics in Appendix A).

2

Statistics save lives.

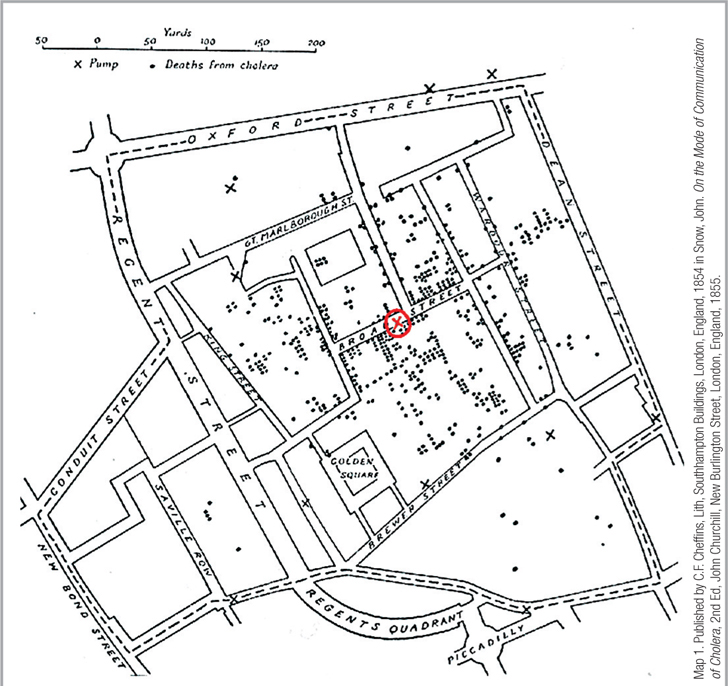

The London cholera epidemic of 1854 hit with terrifying swiftness. Some 500 people died during the first 10 days and no one could figure out why. Everyone involved only knew that the disease dehydrated its victims in gruesome ways no matter how much water the sufferer drank. It was as if an angel of death had decided, during that late summer of 1854, to take a random stroll through London’s Golden Square neighborhood. A workhouse with 535 inmates had only a few mortalities; a nearby brewery with 70 employees was untouched by the epidemic; yet another nearby factory suffered 18 deaths.

Dr. John Snow had spent years trying to determine how cholera was communicated from one person to another (Vinten-

Snow proposed a simple solution: remove the pump handle—