1.2 How to Transform Observations into Variables

A variable is any observation of a physical, attitudinal, or behavioral characteristic that can take on different values.

Like John Snow, we begin the research process by making observations and transforming them into a useful format. For example, Snow observed the locations of people who had died of cholera and placed these locations on a map that also showed wells in the area. Variables are observations of physical, attitudinal, and behavioral characteristics that can take on different values. Behavioral scientists often study abstract variables such as motivation and self-

A discrete observation can take on only specific values (e.g., whole numbers); no other values can exist between these numbers.

Researchers use both discrete and continuous numerical observations to quantify variables. Discrete observations can take on only specific values (e.g., whole numbers); no other values can exist between these numbers. For example, if we measured the number of times study participants get up early in a particular week, the only possible values would be whole numbers. It is reasonable to assume that each participant could get up early 0 to 7 times in any given week but not 1.6 or 5.92 times.

A continuous observation can take on a full range of values (e.g., numbers out to several decimal places); an infinite number of potential values exists.

Continuous observations can take on a full range of values (e.g., numbers out to several decimal places); an infinite number of potential values exists. For example, a person might complete a task in 12.83912 seconds. The possible values are continuous, limited only by the number of decimal places we choose to use.

Discrete Observations

A nominal variable is a variable used for observations that have categories, or names, as their values.

Two types of observations are always discrete: nominal variables and ordinal variables. Nominal variables are used for observations that have categories, or names, as their values. For example, when entering data into a statistical computer program, a researcher might code male participants with the number 1 and female participants with the number 2. In this case, the numbers only identify the gender category for each participant. They do not imply any other quality—

An ordinal variable is a variable used for observations that have rankings (i.e., 1st, 2nd, 3rd …) as their values.

Ordinal variables are used for observations that have rankings (i.e., 1st, 2nd, 3rd …) as their values. In reality television shows, like Britain’s Got Talent or American Idol, for example, a performer finishes the season in a particular place, or rank. Whether or not the performer goes on to get a record deal, fame, and fortune is determined by his or her rank at the end of the season. It doesn’t matter if the performer was first because she was slightly more talented than the next performer or much, much more talented. Like nominal variables, ordinal variables are always discrete. A singer could be 1st or 3rd or 12th but could not be ranked 1.563.

5

Continuous Observations

An interval variable is a variable used for observations that have numbers as their values; the distance (or interval) between pairs of consecutive numbers is assumed to be equal.

The two types of observations that can be continuous are interval variables and ratio variables. Interval variables are used for observations that have numbers as their values; the distance (or interval) between pairs of consecutive numbers is assumed to be equal. For example, temperature is an interval variable because the interval from one degree to the next is always the same. Some interval variables are also discrete variables, such as the number of times one has to get up early each week. This is an interval variable because the distance between numerical observations is assumed to be equal. The difference between 1 and 2 times is the same as the difference between 5 and 6 times. However, this observation is also discrete because, as noted earlier, the number of days in a week cannot be anything but a whole number. Several behavioral science measures are treated as interval measures but also can be discrete, such as some personality and attitude measures.

A ratio variable is a variable that meets the criterion for an interval variable but also has a meaningful zero point.

Sometimes discrete interval observations, such as the number of times one has to get up early each week, are also ratio variables, variables that meet the criteria for interval variables but also have meaningful zero points. If someone never has to get up early, then zero is a meaningful observation and could represent a variety of life circumstances. Perhaps the person is unemployed, retired, ill, or merely on vacation. The number of times a rat pushes a lever to receive food would also be considered a discrete ratio variable in that it has a true zero point—

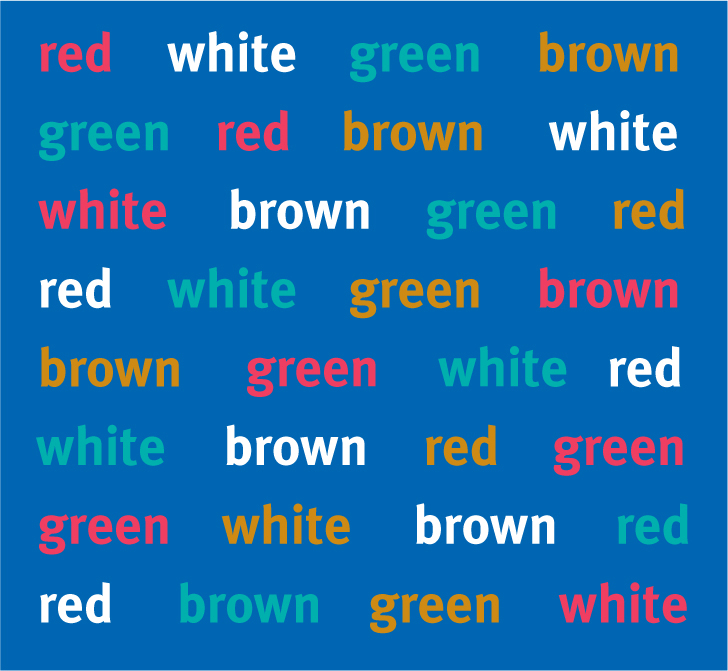

Figure 1-

Many cognitive studies use the ratio variable of reaction time to measure how quickly we process difficult information. For example, the Stroop test assesses how long it takes to read a list of color words printed in ink of the wrong color (Figure 1-1), such as when the word red is printed in blue or the word blue is printed in green. If it takes you 1.264 seconds to press a computer key that accurately identifies that the word red printed in blue actually reads red, then your reaction time is a ratio variable; time always implies a meaningful zero.

MASTERING THE CONCEPT

1.2: The three main types of variables are nominal (or categorical), ordinal (or ranked), and scale. The third type (scale) includes both interval variables and ratio variables; the distances between numbers on the measure are meaningful.

A scale variable is a variable that meets the criteria for an interval variable or a ratio variable.

Many statistical computer programs refer to both interval numbers and ratio numbers as scale observations because both interval observations and ratio observations are analyzed with the same statistical tests. Specifically, a scale variable is a variable that meets the criteria for an interval variable or a ratio variable. Throughout this text, we use the term scale variable to refer to variables that are interval or ratio, but it is important to remember the distinction between interval variables and ratio variables. Table 1-1 summarizes the four types of variables.

6

| Discrete | Continuous | |

|---|---|---|

| Nominal | Always | Never |

| Ordinal | Always | Never |

| Interval | Sometimes | Sometimes |

| Ratio | Seldom | Almost always |

CHECK YOUR LEARNING

Reviewing the Concepts

- Variables are quantified with discrete or continuous observations.

- Depending on the study, statisticians select nominal, ordinal, or scale (interval or ratio) variables.

Clarifying the Concepts

- 1-

4 What is the difference between discrete observations and continuous observations?

Calculating the Statistics

- 1-

5 Three female students complete a Stroop test. Lorna finishes in 12.67 seconds; Desiree finishes in 14.87 seconds; and Marianne finishes in 9.88 seconds.- Are these data discrete or continuous?

- Is the variable an interval or a ratio observation?

- On an ordinal scale, what is Lorna’s score?

Applying the Concepts

- 1-

6 Eleanor Stampone (1993) randomly distributed pieces of paper to students in a large lecture center. Each paper contained one of three short paragraphs that described the interests and appearance of a female student. The descriptions were identical in every way except for one adjective. The student was described as having “short,” “mid-length,” or “very long” hair. At the bottom of each piece of paper, Stampone asked the participants (both female and male) to fill out a measure that indicated the probability that the student described in the scenario would be sexually harassed. - What is the nominal variable used in Stampone’s hair-

length study? Why is this considered a nominal variable? - What is the ordinal variable used in the study? Why is this considered an ordinal variable?

- What is the scale variable used in the study? Why is this considered a scale variable?

- What is the nominal variable used in Stampone’s hair-

Solutions to these Check Your Learning questions can be found in Appendix D.

7