5.2 Probability

You have probably heard phrases such as “the margin of error” or “plus or minus 3 percentage points,” especially during an election season. These are another way of saying, “We’re not 100% sure that we can believe our own results.” This could make you cynical about statistics—

You would be more justified, however, in celebrating statistics for being so truthful—

Coincidence and Probability

Confirmation bias is our usually unintentional tendency to pay attention to evidence that confirms what we already believe and to ignore evidence that would disconfirm our beliefs. Confirmation biases closely follow illusory correlations.

Illusory correlation is the phenomenon of believing one sees an association between variables when no such association exists.

Probability and statistical reasoning can save us from ourselves when, for example, we are confronted with eerie coincidences. Two personal biases get intertwined in our thinking so that we say with genuine astonishment, “Wow! What are the chances of that?” Confirmation bias is our usually unintentional tendency to pay attention to evidence that confirms what we already believe and to ignore evidence that would disconfirm our beliefs. It is a confirmation bias when an athlete attributes her team’s wins to her lucky earrings, ignoring any losses while wearing them or any wins while wearing other earrings. Confirmation biases closely follow illusory correlations. Illusory correlation is the phenomenon of believing one sees an association between variables when no such association exists. An athlete with a confirmation bias attributing wins to her lucky earrings now believes an illusory correlation. We invite illusory correlations into our lives whenever we ignore the gentle, restraining logic of statistical reasoning.

108

For example, the science show Radiolab told a remarkable story of coincidence (Abumrad & Krulwich, 2009). A 10-

The chances seem unbelievably slim, but confirmation bias and illusory correlations both play a role here—

MASTERING THE CONCEPT

5.3: Human biases result from two closely related concepts. When we notice only evidence that confirms what we already believe and ignore evidence that refutes what we already believe, we’re succumbing to the confirmation bias. Confirmation biases often follow illusory correlations—

The Radiolab story described this phenomenon as the “blade of grass paradox.” Imagine a golfer hitting a ball that flies way down the fairway and lands on a blade of grass. The radio show imagines the blade of grass saying: “Wow. What are the odds that that ball, out of all the billions of blades of grass…just landed on me?” Yet we know that there’s almost a 100% chance that some blade of grass was going to be crushed by that ball. It just seems miraculous to the individual blade of grass—

Let’s go back to our story about the Laura Buxtons. A statistician pointed out that the details were “manipulated” to make for a better story. The host had remembered that they were both 10 years old, yet the first Laura reminded him she was still 9 at the time (“almost 10”). The host also admitted there were many discrepancies—

109

Expected Relative-Frequency Probability

Personal probability is a person’s own judgment about the likelihood that an event will occur; also called subjective probability.

When we discuss probability in everyday conversation, we tend to think of what statisticians call personal probability: a person’s own judgment about the likelihood that an event will occur; also called subjective probability. We might say something like “There’s a 75% chance I’ll finish my paper and go out tonight.” We don’t mean that the chance we’ll go out is precisely 75%. Rather, this is our rating of our confidence that this event will occur. It’s really just our best guess.

MASTERING THE CONCEPT

5.4: In everyday life, we use the word probability very loosely—

Probability is the likelihood that a particular outcome—

Mathematicians and statisticians, however, use the word probability a bit differently. Statisticians are concerned with a different type of probability, one that is more objective. In a general sense, probability is the likelihood that a particular outcome—

The expected relative-

Language Alert! In statistics, we are interested in an even more specific definition of probability—

In reference to probability, a trial refers to each occasion that a given procedure is carried out.

In reference to probability, outcome refers to the result of a trial.

In reference to probability, success refers to the outcome for which we’re trying to determine the probability.

In reference to probability, the term trial refers to each occasion that a given procedure is carried out. For example, each time we flip a coin, it is a trial. Outcome refers to the result of a trial. For coin-

110

EXAMPLE 5.1

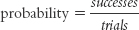

We can think of probability in terms of a formula. We calculate probability by dividing the total number of successes by the total number of trials. So the formula would look like this:

If we flip a coin 2000 times and get 1000 heads, then:

Here is a recap of the steps to calculate probability:

STEP 1: Determine the total number of trials.

STEP 2: Determine the number of these trials that are considered successful outcomes.

STEP 3: Divide the number of successful outcomes by the number of trials.

People often confuse the terms probability, proportion, and percentage. Probability, the concept of most interest to us right now, is the proportion that we expect to see in the long run. Proportion is the number of successes divided by the number of trials. In the short run, in just a few trials, the proportion might not reflect the underlying probability. A coin flipped six times might have more or fewer than three heads, leading to a proportion of heads that does not parallel the underlying probability of heads. Both proportions and probabilities are written as decimals.

Percentage is simply probability or proportion multiplied by 100. A flipped coin has a 0.50 probability of coming up heads and a 50% chance of coming up heads. You are probably already familiar with percentages, so simply keep in mind that probabilities are what we would expect in the long run, whereas proportions are what we observe.

One of the central characteristics of expected relative-

Independence and Probability

Language Alert! To avoid bias, statistical probability requires that the individual trials be independent, one of the favorite words of statisticians. Here we use independent to mean that the outcome of each trial must not depend in any way on the outcome of previous trials. If we’re flipping a coin, then each coin flip is independent of every other coin flip. If we’re generating a random numbers list to select participants, each number must be generated without thought to the previous numbers. In fact, this is exactly why humans can’t think randomly. We automatically glance at the previous numbers we have generated in order to best make the next one “random.” Chance has no memory, and randomness is, therefore, the only way to assure that there is no bias.

111

CHECK YOUR LEARNING

Reviewing the Concepts

- Probability theory helps us understand that coincidences might not have an underlying meaning; coincidences are probable when we think of the vast number of occurrences in the world (billions of interactions between people daily).

- An illusory correlation refers to perceiving a connection where none exists. It is often followed by a confirmation bias, whereby we notice occurrences that fit with our preconceived ideas and fail to notice those that do not.

- Personal probability refers to a person’s own judgment about the likelihood that an event will occur; also called subjective probability.

- Expected relative-

frequency probability is the likelihood of an event occurring, based on the actual outcome of many, many trials. - The probability of an event occurring is defined as the expected number of successes (the number of times the event occurred) out of the total number of trials (or attempts) over the long run.

- Proportions over the short run might have many different outcomes, whereas proportions over the long run are more indicative of the underlying probabilities.

Clarifying the Concepts

- 5-

5 Distinguish the personal probability assessments we perform on a daily basis from the objective probability that statisticians use.

Calculating the Statistics

- 5-

6 Calculate the probability for each of the following instances.- 100 trials, 5 successes

- 50 trials, 8 successes

- 1044 trials, 130 successes

Applying the Concepts

- 5-

7 Consider a scenario in which a student wonders whether men or women are more likely to use the banking machine in the student center. He decides to observe those who use the banking machine. (Assume that there is no gender difference.)- Define success as a woman using the banking machine on a given trial. What proportion of successes might this student expect to observe in the short run?

- What might this student expect to observe in the long run?

Solutions to these Check Your Learning questions can be found in Appendix D.

112