Chapter 1. LAB 1 Introduction to Biological Inquiry

Introduction

Learning Goals

- Understand how to take accurate and precise measurement data and how to present data in figures and tables

- Know the distinction between quantitative and qualitative data

- Analyze data to search for patterns, read specialized graphs, and explore the conclusions that can logically be drawn from them

- Understand how to critically distinguish conclusions from sources of error or variability and from data collection limitations

- Learn a systematic approach to reading scientific literature

- Plan a multi-week scientific literature project

Lab Outline

Activity 1: The Process of Science

Activity 1A: Scientific Investigations

Activity 1B: Exploring Primary Stem Growth

Activity 2: Survey and Read a Scientific Literature Article

Activity 3: Poster Presentation Plan

1.1 Scientific Inquiry

Experiments on Drip Tips

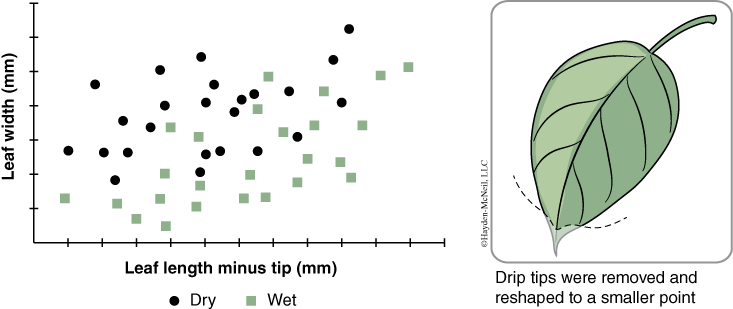

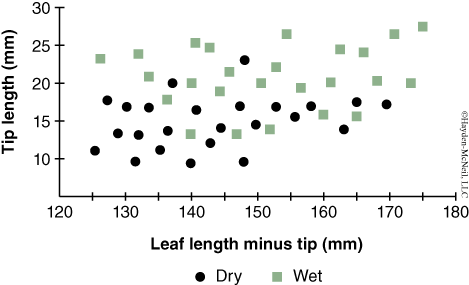

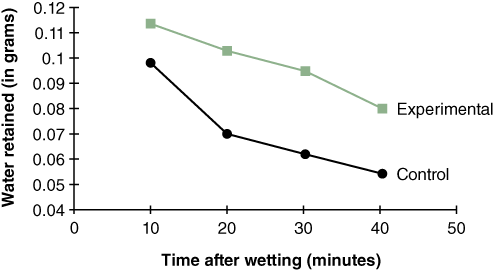

Leaves in wet tropical habitats commonly have simple leaf shapes with “drip tips.” Could this mean that drip tips have adaptive value in this habitat? Plants in dense, wet tropical environments have to compete for light so the leaves are adapted for capturing and competing for light. Water on the surface of leaves tends to reflect light away from the photosynthesis cells in leaves so Lightbody (1985) and Dean and Smith (1978) studied the effect of the presence of drip tips on the ability of tropical leaves to shed excess water. Lightbody’s experiments (Figures 1, 2, and 3) were conducted on the genus Piper, and Dean and Smith’s experiments used the species Machaerium arboretum. In both sets of experiments the control leaves were left intact with their drip tips while the experimental leaves had drip tips removed. The investigations documented leaf shape characteristics and water shedding measurements taken on plants living in either wet or dry habitats.

Notice that the researchers presented their data in graphical form (Figures 1, 2, and 3 were modified from Lightbody 1985; Dean and Smith 1978). The graphs in Figures 1 and 2 are called scatter graphs, which compare two sets of measured data for the same object, such as leaf length (x-axis) and leaf width (y-axis) for each leaf measured. There are many values for the length–width measurements of the leaves which create a scatter of data points, hence the name “scatter graph.” The graph in Figure 3 is called a line graph and relates continuous data, in this case changes in the variable “amount of water retained” over time.

How would you attempt to read a scatter graph? First, read the axes’ labels and note what variables are being compared to each other. Next, read the graph key to determine if there is additional information provided about the data points. In Figure 1, the comparison is made between leaf length (with the drip tip removed) and leaf width. Based on the key, these measurements were taken on leaves from two different habitats, wet and dry. As you study the data points, do you see a trend? For example, how would you characterize the relative shapes of leaves from wet vs. dry tropical habitats? Are thin and long leaves more common in wetter or drier habitats?

In Figure 2 the axes are set up to show the relationship between leaf length (with the drip tip removed) and tip length. Are the drip tips longer in wet or dry habitats? Is there a positive relationship between drip tip length and leaf length, i.e., does drip tip length increase as leaves grow longer? What other information might be helpful for interpreting Figures 1 and 2? Would a best-fit line for each microhabitat provide useful information? Figure 3 shows the relationship between weight and time for control and experimental leaves. Does this relationship appear to be linear for both types of leaves? Which kind of leaf, control or experimental, sheds water faster?

Finally, presentation of the data in graphs allows us to visually view the results and quickly draw conclusions about the distribution of longer drip tips and the role drip tips play in facilitating water shedding in wetter habitats. The clarity of data presentation is critical when communicating findings in science such as those by Lightbody (1985) and Dean and Smith (1978), but it is also important for you as a student when you report findings from experiments completed in a lab course.

1.2 Background

Scientific Investigations in Biology

BIO 204-5 are the introductory biology laboratory courses designed to train you to use those essential processes necessary to conducting scientific investigations in biology. You will find that mere memorization and quiet study are not sufficient to learn how science is actually conducted. The skills necessary to perform scientific investigations take lots of practice, such as thinking about challenging questions, a great deal of problem solving, making connections between ideas that may not initially seem related, use of equipment including sophisticated instrumentation, appropriate statistical analysis, reading scientific literature, and strong skills in oral and written communication. Professional conduct for scientists and health care workers requires them to be committed to high ethical standards. They must be honest with regard to conveying the truth and honoring commitments, accurate in recording and reporting data, efficient to avoid wasting resources, and should look at evidence as unbiased and objective observers. BIO 204 is designed to introduce you to these skills and develop your ability to perform them proficiently.

In biology, living organisms past, present, and future are fair game for scientific investigation; however, the investigative instruments, statistical analyses, types of communication, and of course, habits of mind, are consistent, at least recognizable to most biologists regardless of the specific field they work in. You will be required to develop and strengthen those habits of mind that are typical of scientific investigators. As part of this course you will be asked to make observations about the natural world and question what you observe. The question tends to lead scientists to investigate further by looking into what is already written about their observation to gain additional insights. This is usually sufficient for the casual observer but someone with a scientific habit of mind will tend to be skeptical and strive to think of the observation from different perspectives. Ideally they will be open-minded and will scrutinize the evidence, whether observational, statistical, or logical, and think creatively to look for flaws in the existing interpretations. As one scientist put it, “If you make an observation and think you know how it works, do as many experiments as you can to prove yourself wrong. If you can’t do it, then you might be ready to publish your results.”

In science, being able to communicate your findings in a publication to make it part of the world of shared human knowledge is essential to be defined as “scientific.” However, just any publication won’t do; science is routinely validated by other knowledgeable individuals who can testify whether the evidence is consistent with current scholarship. This validation process is called peer review and scientists who want their research accepted by the larger community of scientists go to conferences to present their work in-person to other experts in their field, and publish their papers in professional peer-reviewed journals. Professional scientific research articles encapsulate the essence of scientific investigations. They present how modern science is practiced in a well-defined and organized format designed to convey the question, experimental approach, evidence, and interpretation of the evidence unambiguously so another scientist can read, understand, and evaluate the value of the evidence and interpretations.

Since you are being trained to become a professional with a background in science, you will learn about scientific investigations in biology by reading an actual research article. The series of assignments that comprise your reading assignment are designed to help you learn to read professional articles, many of which are highly specialized, and may at first seem quite inscrutable, so that you will not only understand them but will be able to present the question, evidence, and interpretations in the article to other students, your peers.

1.3 Scientific Literature Project

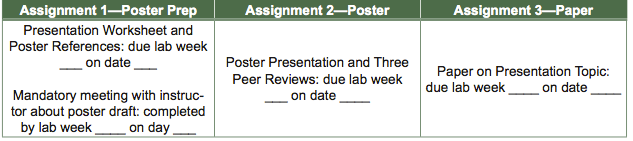

The BIO 204 “Sci Lit” spans several weeks. Activities 2–3 in today’s lab will prepare you for the assignments that make up the project.

- In Activity 2, you will learn to read these articles using a reading strategy. This is a stepwise process designed to train you to quickly determine the salient points of scientific papers. These activities will prepare you to deliver a formal presentation on a research article later this semester.

- In Activity 3, you will learn to plan and outline an oral presentation of a research article using a specially designed worksheet that will help you organize the main points in a paper. About a month from now you will present your article in class to your peers and receive constructive feedback from them to help you improve your presentation. Finally, you will write a paper that summarizes the research article, what you learned from it about science, and future directions this kind of research might take. Follow the schedule below for the scientific literature project:

Schedule of Assignments for the Scientific Literature Project

1.4 Resources

1.5 Lab Preparation

Lab Preparation

Watch the vodcast and read this lab. Place all notes in your lab notebook. Review the course information located at the beginning of the lab manual.

1.6 Activity 1: The Process of Science

Activity 1A: Scientific Investigations

Scientific investigations are much like mystery stories you see on TV or read in books. The detective looks for evidence, whether motive, location, weapon, or items at the scene of the crime, and when the evidence consistently points to the same conclusion, the case can be solved, though often the detective has to be clever to see the consistency in connections present in the evidence.

Answer the Following Questions for a Class Discussion

- If you examined a picture of people in Times Square and everyone was wearing heavy coats, boots, and hats, what might this suggest about the weather? What might be misleading about this evidence?

- If you examined another picture taken on the same day showing Central Park and there were no leaves on the trees, is this evidence consistent with the evidence from Times Square? How could this evidence be misleading?

- Can we use such observations to make more detailed statements about the weather over time? Specifically, could we use tree growth as an indicator of weather conditions from one year to the next? Is there a relationship between annual tree growth and weather conditions during the growing seasons? Explain.

- How do deciduous trees grow? Do they grow longer, wider, up or down? If you’re planning to monitor tree growth, what parts of a tree would you use to take measurements: its leaves, twigs, branches, the trunk, roots, or flowers? Why?

- In the winter, most deciduous trees are dormant and very little growth occurs at this time. Growth begins again in the spring and stops in the fall. Based on the tree part you chose, could you measure the amount of growth that occurred from spring to fall? Look at a tree branch. Which part is oldest? Where does the most recent growth occur? Can you see where growth stopped last winter and started again in the spring?

- What type of growth occurs when tree branches and twigs lengthen? Primary or secondary?

- What kind of growth makes trees wider and sturdier? Primary or secondary?

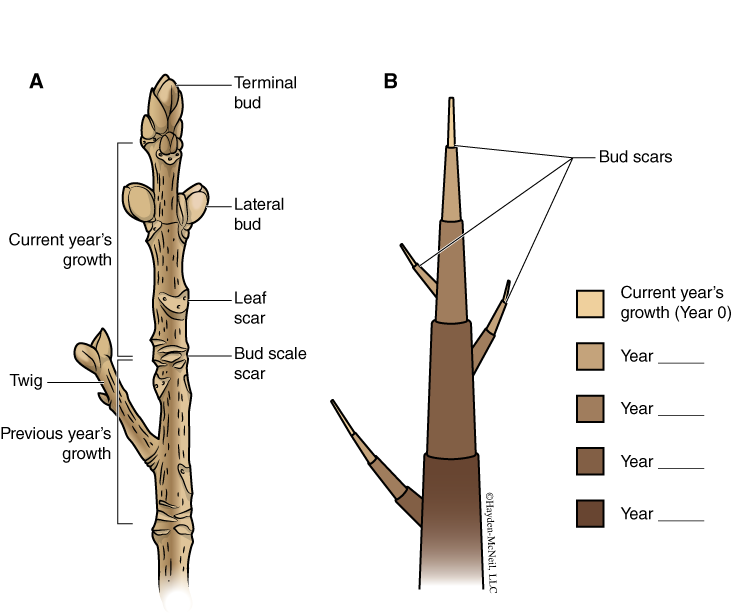

- In lab you will use tree growth (Activity 1B) to seek consistent patterns from year to year by measuring the distance between bud scars. Examine Figure 4A and complete the labeling of Figure 4B.

- Since the weather is about the same for all species of trees living in the same area, should growth evidence be the same from one species to the next? Why or why not?

- Since the weather is about the same for a particular tree, should there be the same amount of growth per year for twigs growing on the same branch? Which side of the tree, north or south, might have more growth?

Summary

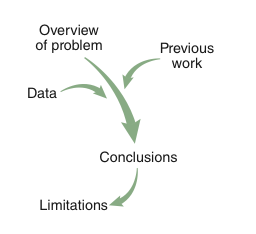

Our inquiry into primary growth will touch upon some of the major steps required when one is conducting a scientific investigation. You will observe and take measurements of part of a living thing to devise questions (Overview of Problem); you will use terms and background information defined by plant biologists (Previous Work); you will collect data, process it, and interpret it (Data); and finally you will draw some conclusions from your findings that are in line with what is known about the system (Conclusions). We hope you will also learn that the conclusions we draw may not be the final answer (Limitations). As stated earlier, the process of science basically tests hypotheses with evidence to formulate scientific explanations that are logical and persuasive, explanations that are also constantly reviewed with additional evidence and revised.

1.7 Activity 1B: Exploring Primary Stem Growth

In temperate climates growth ceases during the winter and resumes in the spring. When growth slows and ceases as winter approaches, the hard bud scales that protect the tender, growing apical meristem cells at the tip of the stem leave a bud scar, a kind of footprint, in the bark of the twig. At the end of each growing season the bud scars along the length of the twig show where growth ceased. The distances at every interval between the tip of the twig and the bud scar, and from that bud scar to the next, are records of the amount of primary growth in a given year (Figure 4A). Also, when the leaves fall off the twig they leave an impression called a leaf scar at the base of lateral buds.

Notice the current year’s growth (lightest color) is narrow, corresponding to the diameter of the bud at the end of the twig (Figure 4B). Each year’s growth is separated by bud scars that mark the position of the bud at the end of a growing season. The older portions of the twig no longer grow in length but they do grow in thickness and each year another layer of secondary growth is added to the twig. This pattern of secondary growth creates the tree rings seen in cut logs. After a while the bud scars are no longer visible when secondary growth layers cover the position of the original bud scars.

Since bud scars can be used as markers for measuring the amount of primary growth this year and in previous years, we can use these measurements to compare growth from one year to the next. In the next activity you will use a branch from a tree to measure differences in primary growth between this year and the previous year’s growth.

1.8 Learning Objectives

After successful completion of this activity, you should be able to:

LO1 Measure yearly primary growth in a woody plant

LO2 Collect quantitative data in a table and graph the data in Excel

LO3 Draw conclusions from a graph of data

Materials

Tree branches from different plant species

Rulers

Tape measure

Calipers

Dissecting scope

1.9 Activity 1B Procedure

- Observe primary and secondary growth in a branch from a tree (Figure 4). How many bud scars are present along the length of the main or apical branch? Sketch the branch and its accompanying lateral branches in your lab notebook. Indicate the positions of the bud scale scars on the apical branch.

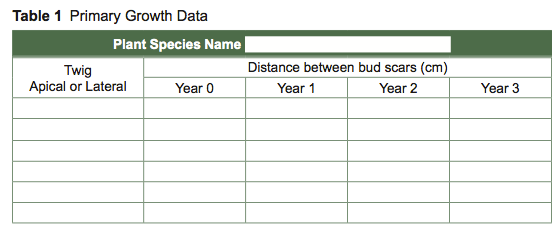

- Measure the distances between each bud scale scar and enter this data into a data table in your lab notebook, similar to Table 1. Write in detail how you took your measurements and the instrument(s) used so the method is reproducible. Do not confuse bud scars with leaf scars; if you do, your data will not reveal information about primary growth.

- Repeat your method and take similar measurements of at least two other lateral branches. Note which group members measured which branches. Why is this important?

1.10 Data Analysis

Additional Information about Excel is available on Blackboard.

- Enter your data into an Excel spreadsheet. Open Excel on your computer, click on the Home tab, and enter your data in the rows (numbered) and columns (letters) in an Excel spreadsheet.

- Create a scatter graph of your data. Highlight your data to select it by clicking on the upper left-most part of the table, and while holding down the left mouse key, drag the highlighted box across the entire data table. Click on the Insert menu tab, and in the Charts ribbon menu select Scatter. In the Scatter drop-down menu, select “scatter with only markers.”

- Check that your data is graphed properly. Once the graph appears, move and resize it as necessary. If your graph appears without a proper “key,” Excel may have graphed your data across, by rows, instead of down, by columns. To check, click on the graph Chart area to select it (it will also box-in the data used to make the graph) and a Chart Tools menu will appear. Click on the Design tab and select “Switch Row/Column” in the ribbon menu. Toggle the selection on and off and note what happens to your graph and how the data highlight changes.

- Properly format your scatter graph. The graph appears as the Excel default form which is usually not appropriate for lab reports. To convert it to the format required for your reports you have to remove the chart title, grid lines, and border, add in axes titles, and a figure legend. The key in the graph is called a “legend” by Excel, but it is not a figure legend as it is known in science, but a key like that on a map. Click on your graph to highlight it and submenus will appear to the side. Select “Chart Elements (+)” and a submenu will appear. Deselect the boxes for chart title and gridlines to remove them from the graph.

- Check Axes Titles in the Chart Elements menu and the placeholder terms “Axis Title” will appear on the x and y-axes of the graph. Double-click in each placeholder and type in the axes titles with the appropriate units in parentheses. You can access the Chart Elements menu also through the ribbon menus of the Design Tab on the Excel menu bar.

- Change the markers on your graph. You can use many of the Format Chart Area menu options to make modifications to your graph. For example, you might prefer a different symbol to the default symbol.

- Right-click on different parts of the graph to access menus directly. You can make changes to your Excel graphs by right-clicking directly on the chart area, plot area, or markers (data points) and Excel menus will appear related to what you clicked on. To remove the graph border, right-click on the chart area and select “Format Chart Area” and the menu should appear to the far right of the spreadsheet as before. Click on “Border” and select “No line.”

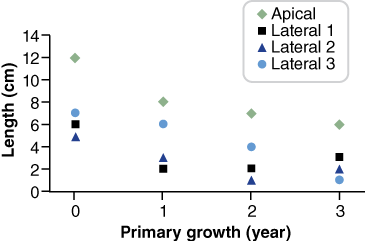

- Add a text box into which you will type a figure legend by selecting the “Insert” menu tab, and “Text Box” from the “Text” ribbon. The figure legend should be descriptive of the results. The figure legend should allow the reader to interpret the graph without having to read the methods or written results. Please note in the final version of the graph the key was moved to the top of the plot area to spread out the graph. Your graph should look similar to Figure 5.

- Interpret your data based on the graph.

- What conclusions can you draw from each set of data?

- What could account for similarities and differences in the amount of primary growth of the twigs on your branch? For example, compare the relative amount of growth of different twigs growing on the same branch. For example, does lateral twig 1 give the same growth rates as lateral twig 2?

- Did the apical twig on your branch grow more than the lateral twigs? It did in our hypothetical example. If so, what could make the apical twig grow more than the others?

- What other factors could have influenced our results? Are there environmental effects such as sunlight exposure that results in more or less primary growth on the sunny side (south-facing) vs. the shady side (north-facing) of a tree?

- Make definitive statements about the relative amounts of primary growth in the twigs on the branch, and based on your basic knowledge of primary growth, propose hypotheses about the reasons why the twigs have different or the same amounts of growth.

- What types of information would be helpful in supporting or refuting your hypothesis? For example, there is Long Island climate data available on the Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL) Meteorology Services site. Do these data agree with your hypothesis?

- Write some conclusions you can draw from your data. What limitations did you encounter in your ability to draw definitive conclusions? This is a common issue in the process of science.

- Each group will present their hypotheses to the class to open a discussion about the possible relationships between primary growth and abiotic factors such as temperature, precipitation, and sunlight with data from BNL Meteorology Services. What other kinds of background information or data might be pertinent to your study as you plan an experimental test of your hypothesis?

1.11 Activity 2: Survey and Read a Scientific Literature Article

Reading Strategies (aka The Secrets of Successful Reading)

Reading with excellent comprehension is necessarily a highly developed skill for academic and professional success. Expert readers can successfully comprehend what they are reading through “directed cognitive effort,” or the conscious awareness of “procedural, purposeful, effortful,” and willful attention to monitoring their understanding of what they read (Taraban et al. 2004). It may come as no surprise to you that highly trained professionals master certain “tricks of the trade” that make reading professional literature needed for their work more efficient—these “tricks” are called “reading strategies” or “reading methodologies,” among other terms. The idea is to use specific, ingrained reading habits to quickly and efficiently learn information from written work. As a pre-professional student you will benefit tremendously from mastering a reading strategy for professional literature.

The Reading Strategy for Professional Scientific Articles

Primary scientific literature is written in a specific format to convey information efficiently. Here are a couple of examples of strategies for reading professional articles:

- Read the abstract—modern journals require structured abstracts that contain the background (hypothesis), methods, results, and conclusions. This provides basic information and does not enable you to think critically or analyze the validity of the content.

- If the article has an abstract, start by reading the conclusion section of the abstract—the idea here is to learn what the author thinks is the most important outcome of the article.

- Read the topic sentence (the first sentence) of each paragraph. If the paper is structured in standard format you can get a sense of the point of the article just from the flow of the ideas derived from these topic sentences.

- Read the title—a well-written title will describe the essence of the paper in a few words and provides key words to use in search engines for additional information.

- Outline the paper and define unfamiliar terms to get an overview of the paper.

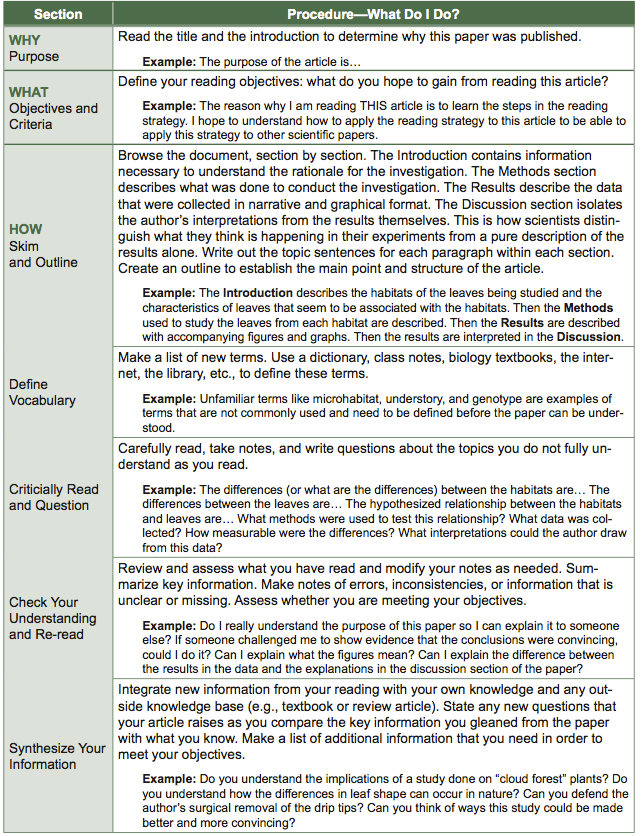

In BIO 204 we present a standardized reading strategy (Table 2) to aid novices with interpreting scientific articles written in the biological sciences. You should apply this reading strategy to learn its major steps and practice your own version of this strategy to develop “specific ingrained reading habits” that allow you to quickly and efficiently glean information from scientific literature. Efficient use of any reading strategy requires a degree of practice before this skill is mastered—in the following activity you will start your practice with an in-class paper.

Scientific Literature Project in BIO 204

Over the next few weeks, you will apply the reading strategy to an assigned primary literature article. You will complete a worksheet based on this strategy to help you identify the major points of your paper and its critical results and conclusions in preparation for your poster and oral presentation.

Learning Objectives

After successful completion of this activity, you should be able to:

LO10 Read scientific journal articles using a reading strategy

LO11 Identify the purpose of an experiment

LO12 Find the methods used in the experiment

LO13 Locate the evidence described in results

LO14 Explain the conclusions drawn in primary literature articles

Materials

Knisely text

A primary literature article

1.12 Activity 2 Procedure

- Locate an article based on the citation provided by your instructor. Save a copy of the article to your flash drive.

- Follow the reading strategy presented in Table 2. Complete the “Why” and “What” sections of the strategy.

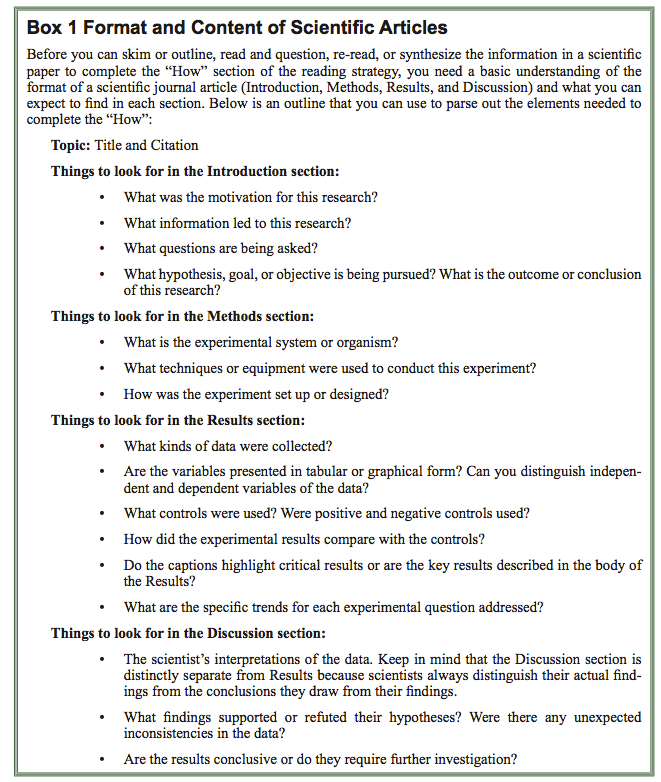

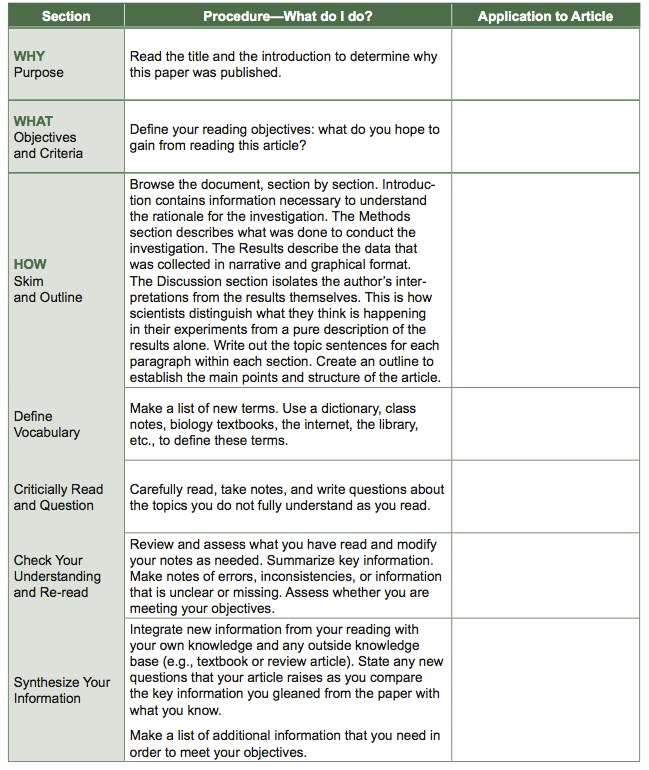

- Complete the parts of the “How” section as designated by your instructor (Table 3). Completion of the “How” section requires an understanding of the “format” of a scientific article (Box 1).

1.13 Applying the Reading Strategy

Compare the steps in the strategy with information in the Lightbody (1985) article to see the correspondence between these steps and an actual article.

Table 2 Reading Strategy

1.14 Applying the Reading Strategy Con't

Compare the steps in the strategy with information in your assigned article.

Table 3 Applying the Reading Strategy

1.15 Activity 3: Poster Presentation Plan

In this activity you will make a plan for your poster presentation according to a schedule of due dates. You will be given the reference to a particular paper to locate using library resources. Each student in your lab will present a different paper—these papers cover a wide range of topics.

Assignment 1: Scientific Literature Worksheet (Due lab week ____ on date ____)

Name ______________________ TA _______________ Section _____ Date ______

What is the topic number of your assigned article and the title of the paper?

# __________ Title__________________________________________________ (Turn in a photocopy of the title page that includes the reference: Author, Journal, Year, and Pages.)

Outline of the main points to be included in your poster presentation of your article:

WHY: Briefly describe the purpose of your article.

WHAT: What do you hope to learn from reading this article?

HOW:

- Skim and outline:

- What is the overall objective of this investigation? Why was the study undertaken?

- What did the investigator hope to learn from doing this investigation?

- Define unfamiliar terms:

- What key terms need to be defined before the investigation can be understood and described?

- Critically read and question:

- What points do you hope to emphasize? What points are you unclear about?

- What data was collected as part of the investigation?

- What is the hypothesis?

- What information is contained in each figure?

- Describe 2–3 results that explain, support, or refute the hypothesis of the paper.

- Describe 2–3 conclusions the authors discuss in the paper.

- Check your understanding and re-read:

- Where am I confused?

- What is the relationship between the data, evidence, and interpretation? Which data make the conclusions convincing?

- Synthesize your information:

- How does this scientific information relate to your own knowledge and experiences?

Assignment 2: Poster Presentation (Due lab week ___ on date ___)

Steps to a Successful Poster Presentation

- View the Poster Presentation podcast and refer to Knisely on “How to Give a Poster Presentation.”

- Use library resources to locate a copy of your research paper.

- Use the strategy for reading your assigned manuscript. View the podcast of an expert describing your research paper.

- Summarize the manuscript on your Project Worksheet.

- To help you formulate ideas for making your presentation more interesting, write down something that interested you in the video or manuscript. If you are having difficulty with this step, see “Research Focus” on your topic table handout or ask your instructor for help.

- Use reference texts, reviews, or other resources to answer any questions that you have about your topic. This will help you learn important definitions and understand key methodologies.

- Bring your summaries to the Biology Learning Center and have an instructor read them. Ask several students to read your summaries and give you feedback.

- Follow the steps in this worksheet to identify key components of your presentation.

- Use this information to create a presentation of no more than 9 pages (8.5′′ × 11′′). You will present your work during lab to three other students. They will give you feedback on your project and you will assess theirs. Turn in your presentation and peer assessments.

Assignment 3: Scientific Literature Paper (Due lab week ___ on date ___)

Your final paper is limited to 5 pages double-spaced and should:

- Give a brief description of the nature of the research article.

- Identify the living population that relates to your assigned topic. Include the biological impact of the issue you are investigating, the mechanics of the natural, treated, or diseased condition.

- Focus on a particular problem or challenge that makes your topic a subject of research and compare alternative explanations and problems posed in doing this kind of research.

- Highlight the evidence that supported the research conclusions.

- Identify possible societal issues surrounding this topic.

- Use the rubric as a guide for this part of the assignment.