Motivating Achievement

B-3 Why is it important to motivate achievement?

Organizational psychologists help motivate employees and keep them engaged. But what motivates any of us to pursue high standards or difficult goals?

Organizational psychologists help motivate employees and keep them engaged. But what motivates any of us to pursue high standards or difficult goals?

Grit

“With a road,” a former neighbor explained, “he hoped new generations of people would return to the north end of Raasay,” restoring its culture (Hutchinson, 2006). Day after day he worked through rough hillsides, along hazardous cliff-faces, and over peat bogs. Finally, 10 years later, he completed his supreme achievement. The road, which the government has since surfaced, remains a visible example of what vision plus determined grit can accomplish. It bids us each to ponder: What “roads”—what achievements—might we, with sustained effort, build in the years before us?

Think of someone you know who seems driven to be the best—to excel at any task where performance can be judged. Now think of someone who is less driven. For psychologist Henry Murray (1938), the difference between these two people is a reflection of their achievement motivation. If you score high in achievement motivation, you have a desire for significant accomplishment, for mastering skills or ideas, for control, and for meeting a high standard.

“Genius is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration.”

Thomas Edison (1847–1931)

Achievement motivation matters. Just how much it matters can be seen in a study that followed the lives of 1528 California children. All had scored in the top 1 percent on an intelligence test. Forty years later, researchers compared those who were most and least successful professionally. The most successful were the most highly motivated—they were ambitious, energetic, and persistent. As children, these individuals had enjoyed more active hobbies. As adults, they participated in more groups and preferred playing sports over watching sports (Goleman, 1980). Gifted children are able learners. Accomplished adults are determined doers. Most of us are energetic doers when starting and finishing a project. It’s easiest—have you noticed?—to get “stuck in the middle,” which is when high achievers keep going (Bonezzi et al., 2011).

Motivation differences also appear in other studies, including those of high school and college students. Self-discipline, not intelligence score, has been the best predictor of school performance, attendance, and graduation honors. Intense, sustained effort predicts success for teachers, too, especially when combined with a positive enthusiasm. Students of these motivated educators make good academic progress (Duckworth et al., 2009).

“Discipline outdoes talent,” conclude researchers Angela Duckworth and Martin Seligman (2005, 2006). It also refines talent. By their early twenties, top violinists have fiddled away 10,000 hours of their life practicing. This is double the practice time of other violin students aiming to be teachers (Ericsson et al., 2001, 2006, 2007).

Similarly, a study of outstanding scholars, athletes, and artists found that all were highly motivated and self-disciplined. They dedicated hours every day to the pursuit of their goals (Bloom, 1985). These achievers became superstars through daily discipline, not just natural talent. Great achievement, it seems, mixes a teaspoon of inspiration with a gallon of perspiration.

B-4

Duckworth has a name for this passionate dedication to an ambitious, long-term goal: grit. Intelligence scores and many other physical and psychological traits can be displayed as a bell-shaped curve. Most scores cluster around an average, and fewer scores fall at the two far ends of the bell shape. Achievement scores don’t follow this pattern. That is why organizational psychologists seek ways to engage and motivate ordinary people to be superstars in their own jobs. And that is why training students in hardiness—resilience under stress—leads to better grades (Maddi et al., 2009).

Satisfaction and Engagement

I/O psychologists know that everyone wins when workers are satisfied with their jobs. For employees, satisfaction with work feeds satisfaction with life. Moreover, lower job stress feeds improved health (Chapter 10).

How do employers benefit from worker satisfaction? Positive moods can translate into greater creativity, persistence, and helpfulness (Brief & Weiss, 2002; Kaplan et al., 2009). The correlation between individual job satisfaction and performance is modest but real (Judge et al., 2001; Ng et al., 2009; Parker et al., 2003). One analysis tracked 4500 employees at 42 British manufacturing companies. The most productive workers tended to be those in satisfying work environments (Patterson et al., 2004). In the United States, the Fortune “100 Best Companies to Work For” have also produced much higher-than-average returns for their investors (Dickler, 2007).

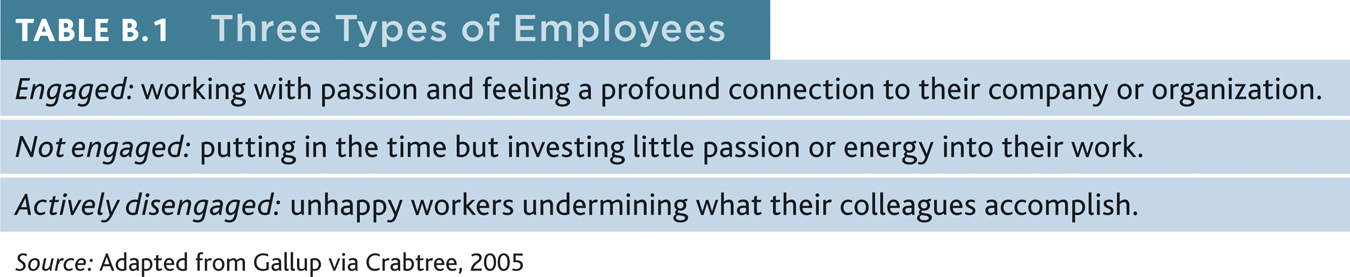

The biggest-ever study of worker satisfaction and job performance was an analysis of Gallup data from more than 198,000 employees (Harter et al., 2002). These people were employed in nearly 8000 business units of 36 large companies, including some 1100 bank branches, 1200 stores, and 4200 teams or departments. The study focused on links between various measures of organizational success and employee engagement—the extent of workers’ involvement, enthusiasm, and identification with their organizations (TABLE B.1). The researchers found that engaged workers (compared with not-engaged workers who are just putting in time) know what’s expected of them, have what they need to do their work, feel fulfilled in their work, have regular opportunities to do what they do best, perceive that they are part of something significant, and have opportunities to learn and develop. They also found that business units with engaged employees have more loyal customers, less turnover, higher productivity, and greater profits.

B-5

But what causal arrows explain this correlation between business success and employee morale and engagement? Does success boost morale, or does high morale boost success? In a follow-up longitudinal study of 142,000 workers, researchers found that, over time, employee attitudes predicted future business success (more than the other way around) (Harter et al., 2010). Many other studies confirm that happy workers tend to be good workers (Ford et al., 2011; Seibert et al., 2011; Shockley et al., 2012). One analysis compared companies with top-quartile versus below-average employee engagement levels. Over a three-year period, earnings grew 2.6 times faster for the companies with highly engaged workers (Ott, 2007).