Leadership

B-4 How can leaders be most effective?

The best leaders want their organization to be successful. They also want the people who work for them and with them to be satisfied, engaged, and productive. To achieve these ends, effective leaders harness people’s strengths, set goals, and choose an appropriate leadership style.

The best leaders want their organization to be successful. They also want the people who work for them and with them to be satisfied, engaged, and productive. To achieve these ends, effective leaders harness people’s strengths, set goals, and choose an appropriate leadership style.

Harnessing Strengths

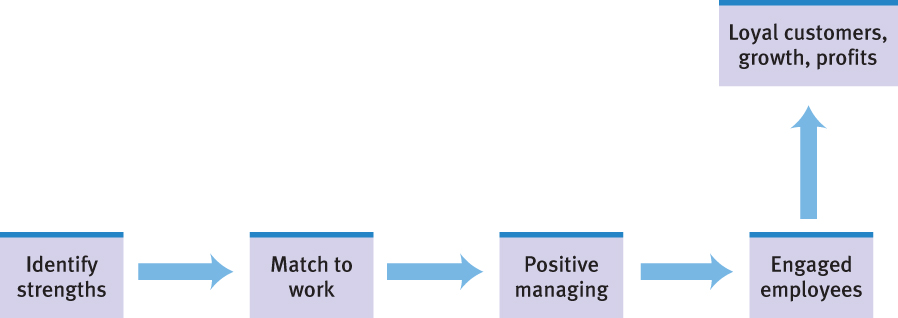

Engaged employees don’t just happen. Effective leaders engage their employees’ interests and loyalty. They figure out people’s natural talents, adjust roles to suit their talents, and develop those talents into great strengths (FIGURE B.1). Consider, for example, instructors at a given school. Should they all be expected to teach the same load? To advise the same number of students? To serve on the same number of committees? To take on the same number of additional responsibilities in the department? Or should their job descriptions be tailored to their specific strengths? Would most schools and their students be better served if instructors’ tasks were matched to their strengths?

Trying to create talents that are not there can be a waste of time. Leaders who excel spend more time developing and drawing out talents that already exist. Effective managers share certain traits (Tucker, 2002). They

- start by helping people identify and measure their talents.

- match tasks to talents and then give people freedom to do what they do best.

- care how people feel about their work.

- reinforce positive behaviors through recognition and reward.

Good managers also try not to promote people into roles ill-suited to their strengths. Imagine that you’re a manager with a limited budget for training. Will you focus on your employees’ weaknesses and send them to training seminars to fix those problems? Or will you focus on educating your employees about their strengths and building upon them? Good managers choose the second option. In Gallup surveys, 77 percent of engaged workers strongly agreed that “my supervisor focuses on my strengths or positive characteristics.” Only 23 percent of not-engaged workers agreed with that statement (Krueger & Killham, 2005).

B-6

Does all this sound familiar? Bringing out the best in people within an organization builds upon a basic principle of operant conditioning (Chapter 6). To teach a behavior, catch a person doing something right and reinforce it. It sounds simple, but too many managers act like the parents who focus on the one low score on a child’s almost-perfect report card. As a report by the Gallup Organization (2004) observed, “65 percent of Americans received no praise or recognition in their workplace last year.”

Setting Specific, Challenging Goals

In study after study, people merely asked to do their best do not do so. Good managers know that a better way to motivate higher achievement is to set specific, challenging goals. For example, you might state your own goal in this course as “Finish studying Appendix B by Friday.” Specific goals focus our attention and stimulate us to work hard, persist, and try creative strategies. Such goals are especially effective when workers or team members participate in setting them. Achieving goals that are challenging yet within our reach boosts our self-evaluation (White et al., 1995).

Stated goals are most effective when combined with progress reports (Johnson et al., 2006; Latham & Locke, 2007). Action plans that break large goals into smaller steps (subgoals) and specify when, where, and how to achieve those steps will increase the chances of completing a project on time (Burgess et al., 2004; Fishbach et al., 2006; Koestner et al., 2002).

Through a task’s ups and downs, people best sustain their mood and motivation when they focus on immediate goals (such as daily study) rather than distant goals (such as a course grade). Better to have one’s nose to the grindstone than one’s eye on the ultimate prize (Houser-Marko & Sheldon, 2008). Thus, before beginning each new edition of this book, my editor, my associates, and I manage by objectives—we agree on target dates for the completion and editing of each chapter draft. If we focus on achieving each of these short-term goals, the prize—an ontime book—takes care of itself. So, to motivate high productivity, effective leaders work with people to define explicit goals, subgoals, and implementation plans, and then they provide feedback on progress.

Choosing an Appropriate Leadership Style

What qualities produce a great leader? Psychologists and others once believed that all great leaders share certain traits. That great person theory of leadership now seems overstated (Vroom & Jago, 2007). The same coach may seem great or not great, depending on the team and its competition. But a leader’s personality does matter (Zaccaro, 2007). Effective leaders are not overly assertive; that trait can damage social relationships within the group. They are not unassertive, because that trait can limit their ability to lead (Ames & Flynn, 2007). Effective leaders of laboratory groups, work teams, and large corporations tend to be self-confident. They have charisma, which seems to have three main ingredients (House & Singh, 1987; Shamir et al., 1993).

- They have a vision of some goal.

- They are able to communicate that vision clearly and simply.

- They have enough optimism and faith to inspire their group to follow them.

Consider a study rating company morale at 50 Dutch firms (de Hoogh et al., 2004). Firms with the highest ratings had chief executives who inspired their colleagues “to transcend their own self-interests for the sake of the collective.” This ability to motivate others to commit themselves to a group’s mission is transformational leadership. Transformational leaders are often natural extraverts. They set their standards high, and they inspire others to share their vision. They pay attention to other people (Bono & Judge, 2004). The frequent result is a workforce that is more engaged, trusting, and effective (Turner et al., 2002). (For an impressive example of transformational leadership skills, see Close-Up: Doing Well While Doing Good.)

Women more than men tend to be transformational leaders. This may help explain why companies with women in top management positions have tended to enjoy superior financial results (Eagly, 2007). That tendency held even after researchers controlled for variables such as company size.

Leadership styles vary, depending both on the qualities of the leader and the demands of the situation. In some situations (think of a commander leading troops into battle), a directive style may be needed (Fiedler, 1981). In other situations, the strategies that work on the battlefield may smother creativity. If developing a comedy show, for example, a leader might get better results using a democratic style that welcomes team member creativity.

B-7

C L O S E - U P

Doing Well While Doing Good—“The Great Experiment”

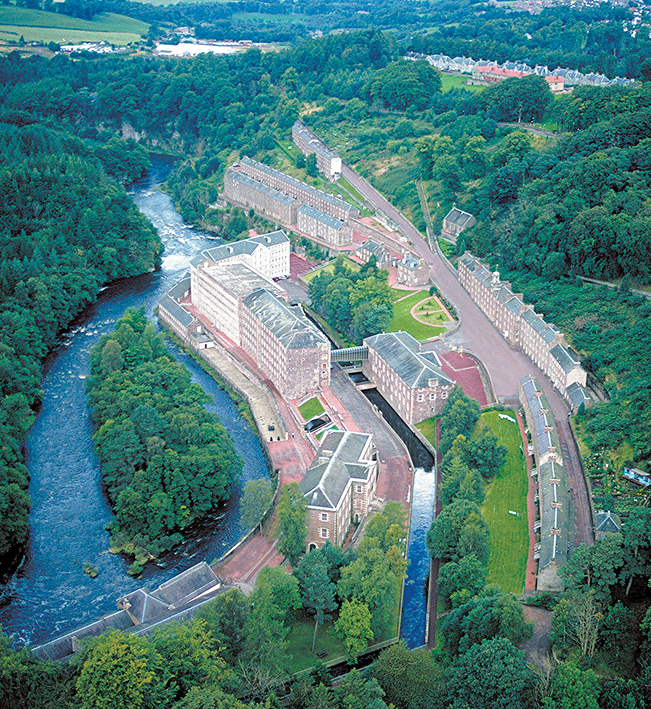

At the end of the 1700s, the cotton mill at New Lanark, Scotland, had more than 1000 workers. Many were children drawn from Glasgow’s poorhouses. They worked 13-hour days and lived in grim conditions. Education and sanitation were neglected. Theft and drunkenness were common. Most families occupied just one room.

On a visit to Glasgow, Welsh-born Robert Owen—an idealistic young cotton-mill manager—chanced to meet and fall in love with the mill owner’s daughter. After their marriage, Owen, with several partners, purchased the mill. On the first day of the 1800s he took control as its manager. Before long, he began what he said was “the most important experiment for the happiness of the human race that had yet been instituted at any time in any part of the world” (Owen, 1814). The abuse of child and adult labor was, he observed, producing unhappy and inefficient workers. Owen believed that better working and living conditions could pay economic dividends.

Owen showed transformational leadership skills when he bravely began many new practices. He started a nursery for preschool children, and education for older children (with encouragement rather than corporal punishment). Workers had Sundays off. They received health care, paid sick days, and unemployment pay for days when the mill could not operate. He set up a company store, selling goods at reduced prices. When his partners resisted his changes, he bought their shares.

Owen also designed a goals and worker-assessment program, with detailed records of daily productivity and costs. By each employee’s workstation, one of four colored boards indicated that person’s performance for the previous day. Owen could walk through the mill and at a glance see how individuals were performing. There was, he said, “no beating, no abusive language…. I merely looked at the person and then at the color…. I could at once see by the expression [which color] was shown.”

The financial success of Owen’s mill supported a reform movement for better working and living conditions. By 1816, with decades of profits still ahead, Owen believed he had demonstrated “that society may be formed so as to exist without crime, without poverty, with health greatly improved, with little if any misery, and with intelligence and happiness increased a hundredfold.” Although that vision has not been fulfilled, Owen’s great experiment did lay the groundwork for employment practices that are accepted in much of the world today.

Leaders differ in the personal qualities they bring to the job. Some excel at task leadership—by setting standards, organizing work, and focusing attention on goals. To keep the group centered on its mission, task leaders typically use a directive style. This style can work well if the leader is smart enough to give good orders (Fiedler, 1987).

Other managers excel at social leadership. They explain decisions, help group members solve their conflicts, and build teams that work well together (Evans & Dion, 1991). Social leaders often have a democratic style. They share authority and welcome the opinions of team members. Social leadership is good for morale. We usually feel more satisfied and motivated and perform better when we can participate in decision making (Cawley et al., 1998; Pereira & Osburn, 2007). Moreover, when members are sensitive to one another and participate equally, groups solve problems with greater “collective intelligence” (Woolley et al., 2010).

Effective managers often exhibit a high degree of both task and social leadership. This finding applies in many locations, including coal mines, banks, and government offices in India, Taiwan, and Iran (Smith & Tayeb, 1989). As achievement-minded people, effective managers certainly care about how well people do their work. Yet they are sensitive to their workers’ needs. That sensitivity is often repaid by worker loyalty. In one national survey of American workers, those in family-friendly organizations offering flexible hours reported feeling greater loyalty to their employers (Roehling et al., 2001).

Employee participation in decision making is common in Sweden, Japan, the United States, and elsewhere (Cawley et al., 1998; Sundstrom et al., 1990). Giving workers a chance to voice their opinion before a decision is made engages them in the process. They then tend to respond more positively to the final decision (van den Bos & Spruijt, 2002). They also feel more empowered and are more creative (Hennessey & Amabile, 2010; Huang et al., 2010).

B-8

The ultimate in employee participation is the employee-owned company. One such company in my town, the Fleetwood Group, is a 165-employee manufacturer of educational furniture and wireless electronic clickers. When its founder gave 45 percent of the company to his employees, who later bought out other family stockholders, Fleetwood became one of America’s first companies with an employee stock ownership plan (ESOP). Today, every employee owns part of the company, and as a group they own 100 percent. The more years employees work, the more they own, yet no one owns more than 5 percent. Like every corporate president, Doug Ruch works for his stockholders, who also just happen to be his employees.

As a company that endorses faith-inspired “servant-leadership” and “respect and care for each team member-owner,” Fleetwood is free to place people above profits. Thus, when orders lagged during the recent recession, the employee-owners decided that job security meant more to them than profits. So the company paid otherwise idle workers to do community service—answering phones at nonprofit agencies, building Habitat for Humanity houses, and the like.

Fleetwood employees “act like they own the place”; Ruch contends that employee ownership attracts and retains talented people, “drives dedication,” and gives Fleetwood “a sustainable competitive advantage.” With stock growth averaging 17 percent a year, Fleetwood was named the 2006 National ESOP of the year.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 17.2

What characteristics are important for transformational leaders?

Transformational leaders are able to inspire others to share a vision and commit themselves to a group’s mission. They tend to be naturally extraverted and set high standards.