Stress: Some Basic Concepts

10-1 How does our appraisal of an event affect our stress reaction, and what are the three main types of stressors?

Stress is a slippery concept. In everyday life, we may use the word to describe threats or challenges (“Ben was under under a lot of stress”) or to describe our responses to those events (“Ben experienced acute stress”). Psychologists use more precise terms. The challenge or event (Ben’s dangerous truck ride) is a stressor. Ben’s physical and emotional responses are a stress reaction. And the process by which he interpreted the threat is stress.

Stress is a slippery concept. In everyday life, we may use the word to describe threats or challenges (“Ben was under under a lot of stress”) or to describe our responses to those events (“Ben experienced acute stress”). Psychologists use more precise terms. The challenge or event (Ben’s dangerous truck ride) is a stressor. Ben’s physical and emotional responses are a stress reaction. And the process by which he interpreted the threat is stress.

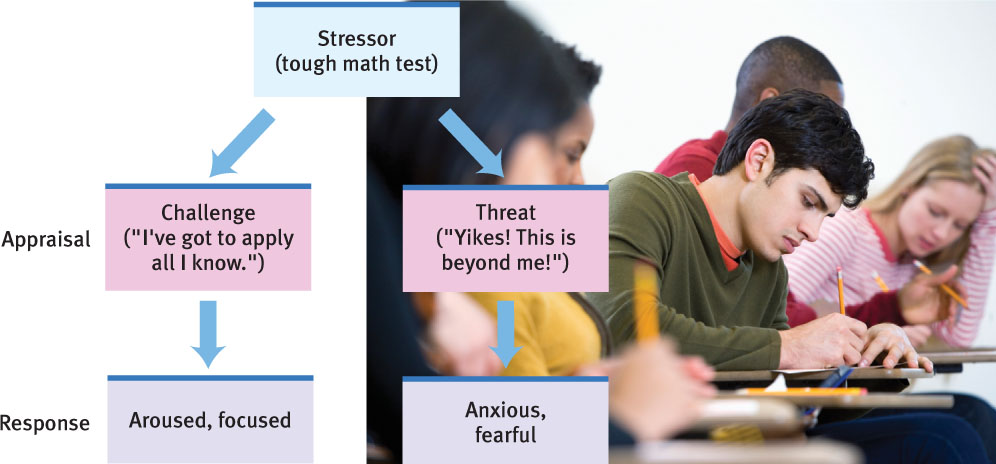

Thus, stress is the process of appraising an event as threatening or challenging, and responding to it (Lazarus, 1998). If you have prepared for an important math test, you may welcome it as a challenge. You will be aroused and focused, and you will probably do well (FIGURE 10.1). Championship athletes, successful entertainers, and great teachers and leaders all thrive and excel when aroused by a challenge (Blascovich & Mendes, 2010).

Stressors that we appraise as threats, not challenges, can instead lead to strong negative reactions. If prevented from preparing for your math test, you will appraise the disruption as a threat, and your response will be distress.

Extreme or prolonged stress can harm us. Demanding jobs that mentally exhaust workers also damage their physical health (Huang et al., 2010). Pregnant women with overactive stress systems tend to have shorter pregnancies, which pose health risks for their infants (Entringer et al., 2011).

So there is an interplay between our head and our health. Before we explore that interplay, let’s take a closer look at types of stressors and stress reactions.

Stressors—Things That Push Our Buttons

Stressors fall into three main types: catastrophes, significant life changes, and daily hassles. All can be toxic—they can increase our risk of disease and death.

Catastrophes

Catastrophes are unpredictable large-scale events, such as earthquakes, floods, wildfires, and storms. Even though we often give aid and comfort to one another after such events, the damage to emotional and physical health is significant. In surveys taken in the three weeks after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, for example, 58 percent of Americans said they were experiencing greater than average arousal and anxiety (Silver et al., 2002). In the four months after Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans reportedly experienced a tripled suicide rate (Saulny, 2006).

Significant Life Changes

During catastrophes, misery often has company. But during significant life changes, we may experience stress alone. Even a happy life change, such as marrying the love of your life, can be a stressor. So can other personal events—leaving home, becoming divorced, having a loved one die. These life changes often happen during young adulthood. The stress of those years was clear in a recent survey that asked, “Are you trying to take on too many things at once?” Who reported the highest stress levels? Women and younger adults (APA, 2009). About half of people in their twenties, but only one-fifth of those over 65, reported experiencing stress during “a lot of the day yesterday” (Newport & Pelham, 2009).

How does stress related to life changes affect our health? Long-term studies indicate that people recently widowed, fired, or divorced are more disease-prone (Dohrenwend et al., 1982; Strully, 2009). In one study of 96,000 widowed people, their risk of death doubled in the week following their partner’s death (Kaprio et al., 1987). Experiencing a cluster of crises (perhaps losing a job and an important relationship while falling behind in schoolwork) puts one even more at risk.

285

Daily Hassles

“It’s not the large things that send a man to the madhouse…no, it’s the continuing series of small tragedies…not the death of his love but the shoelace that snaps with no time left.”

American author Charles Bukowski (1920–1994)

Events don’t have to remake our lives to cause stress. Stress also comes from daily hassles—spotty cell-phone connections, irritating housemates, long lines at the store, too many things to do, e-mail and text spam, and loud cell-phone talkers (Lazarus, 1990; Pascoe & Richman, 2009; Ruffin, 1993). Some people simply shrug off such hassles. Others find them hard to ignore. This is especially the case for the many Americans who wake up each day facing budgets that won’t stretch to the next payday, housing problems, solo parenting, poor health, perceived discrimination, and unreachable goals. Such stressors can take a toll on physical and mental well-being.

Stress Reactions—From Alarm to Exhaustion

10-2 How does the body respond to stress?

Our response to stress is part of a unified mind-body system. Walter Cannon (1929) first realized this in the 1920s. He found that extreme cold, lack of oxygen, and emotion-arousing events all trigger an outpouring of stress hormones from the adrenal glands. When your brain sounds an alarm, your sympathetic nervous system (Chapter 2) responds. It increases your heart rate and respiration, diverts blood from your digestive organs to your skeletal muscles, dulls your feeling of pain, and releases sugar and fat from your body’s stores. All this prepares your body for the wonderfully adaptive fight-or-flight response (see Figure 9.13 in Chapter 9).

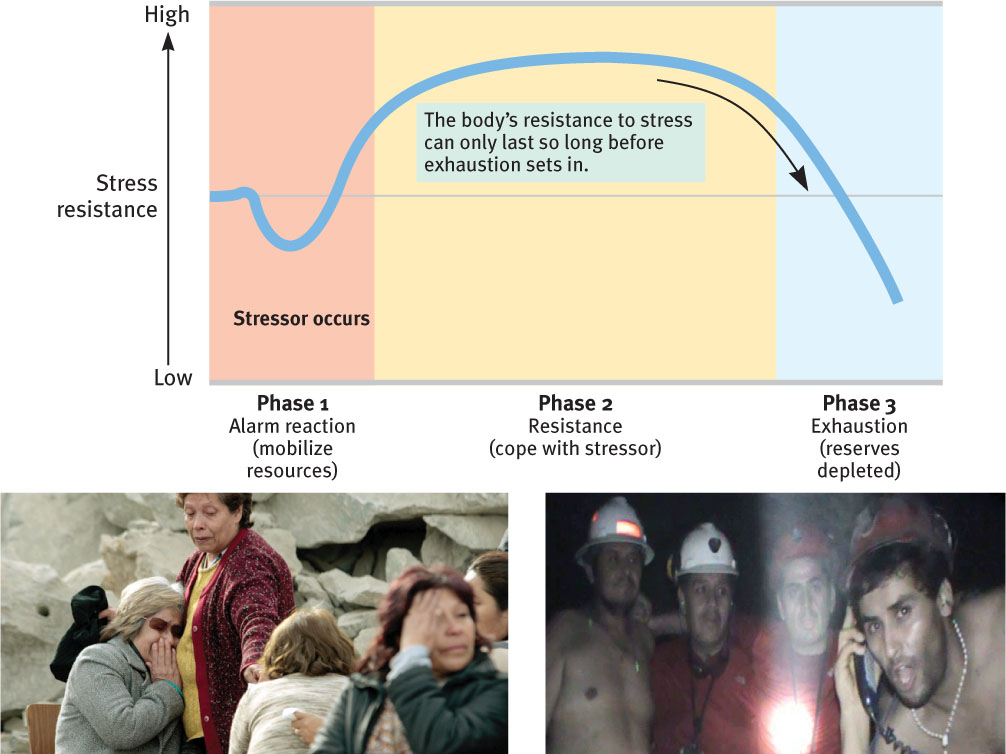

Hans Selye (1936, 1976) extended Cannon’s findings. His studies of animals’ reactions to various stressors, such as electric shock and surgery, helped make stress a major concept in both psychology and medicine. Selye discovered that the body’s adaptive response to stress was so general that it was like a single burglar alarm that sounds, no matter what intrudes. He named this response the general adaptation syndrome (GAS), and he saw it as a three-stage process (FIGURE 10.2). Here’s how those stages, or phases, might look if you suffered a physical or emotional trauma:

- In Phase 1, you have an alarm reaction, as your sympathetic nervous system suddenly activates. Your heart rate soars. Blood races to your skeletal muscles. You feel the faintness of shock.

- During Phase 2, resistance, your temperature, blood pressure, and respiration remain high. With your resources mobilized, you are ready to fight back. Your adrenal glands pump stress hormones into your bloodstream. You are fully engaged, summoning all your resources to meet the challenge.

- In Phase 3, constant stress causes exhaustion. As time passes, with no relief from stress, your reserves begin to run out. Your body copes well with temporary stress, but prolonged stress can damage it. You become more vulnerable to illness or even, in extreme cases, collapse and death. Rats show similar patterns. The most fearful and easily stressed rats die about 15 percent sooner than their more confident counterparts (Cavigelli & McClintock, 2003).

There are other options for dealing with stress. One is a common response to a loved one’s death: Withdraw. Pull back. Conserve energy. Faced with an extreme disaster, such as a car sinking in a body of water, some people become paralyzed by fear. They stay strapped in their seatbelt instead of paddling to safety. Another option for dealing with stress is to seek and give support. Perhaps you have participated in this tend-and-befriend response by contributing help after some natural disaster.

286

AP Photo/Chile’s Presidency

The tend-and-befriend response is found especially among women (Taylor et al., 2000, 2006). Facing stress, men more often than women tend to socially withdraw, turn to alcohol, or become aggressive. Women more often respond to stress by nurturing and banding together, which may be due to oxytocin. This stress-moderating hormone is associated with pair-bonding in animals and is released by cuddling, massage, and breast feeding in humans (Taylor, 2006). Women in distressed relationships have higher levels of oxytocin, which may help them seek out and receive support from others (Taylor et al., 2010).

It often pays to spend our physical and mental resources in fighting or fleeing an external threat. But we do so at a cost. When our stress is momentary, the cost is small. When stress persists, we may pay a much higher price, with lowered resistance to infections and other threats to mental and physical health.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 10.1

Stress response system: When alerted to a negative, uncontrollable event, our _______ nervous system arouses us. Heart rate and respiration _______ (increase/decrease). Blood is diverted from digestion to the skeletal _______. The body releases sugar and fat. All this prepares the body for the ________-_______-________ response.

sympathetic; increase; muscles; fight-or-flight