Stress Effects and Health

10-3 How does stress influence our immune system?

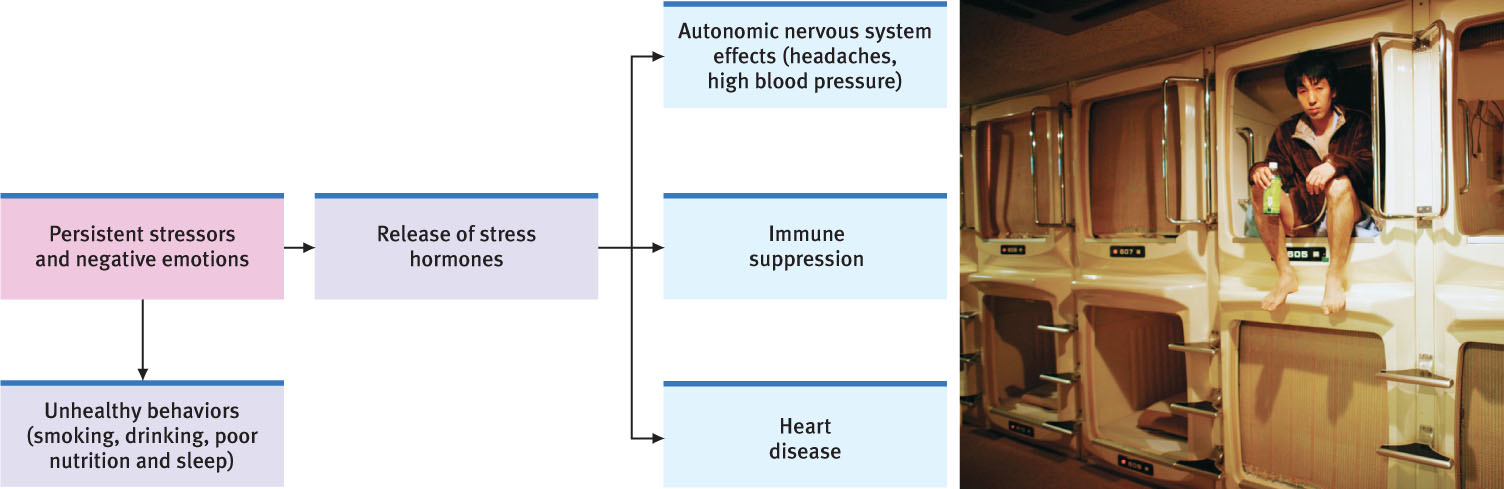

How do you try to stay healthy? Avoid sneezers? Get extra rest? Wash your hands? You should add stress management to that list. Why? Because, as we have seen throughout this text, everything psychological is also biological. Stress is no exception. Stress contributes to high blood pressure and headaches. Stress also leaves us less able to fight off disease. To manage stress, we need to understand these connections.

How do you try to stay healthy? Avoid sneezers? Get extra rest? Wash your hands? You should add stress management to that list. Why? Because, as we have seen throughout this text, everything psychological is also biological. Stress is no exception. Stress contributes to high blood pressure and headaches. Stress also leaves us less able to fight off disease. To manage stress, we need to understand these connections.

The field of psychoneuroimmunology studies our mind-body interactions (Kiecolt-Glaser, 2009). That mouthful of a word makes sense when said slowly. Your emotions (psycho) affect your brain (neuro), which controls the stress hormones that influence your disease-fighting immune system. And this field is the study of (ology) those interactions. Let’s start by focusing on the immune system.

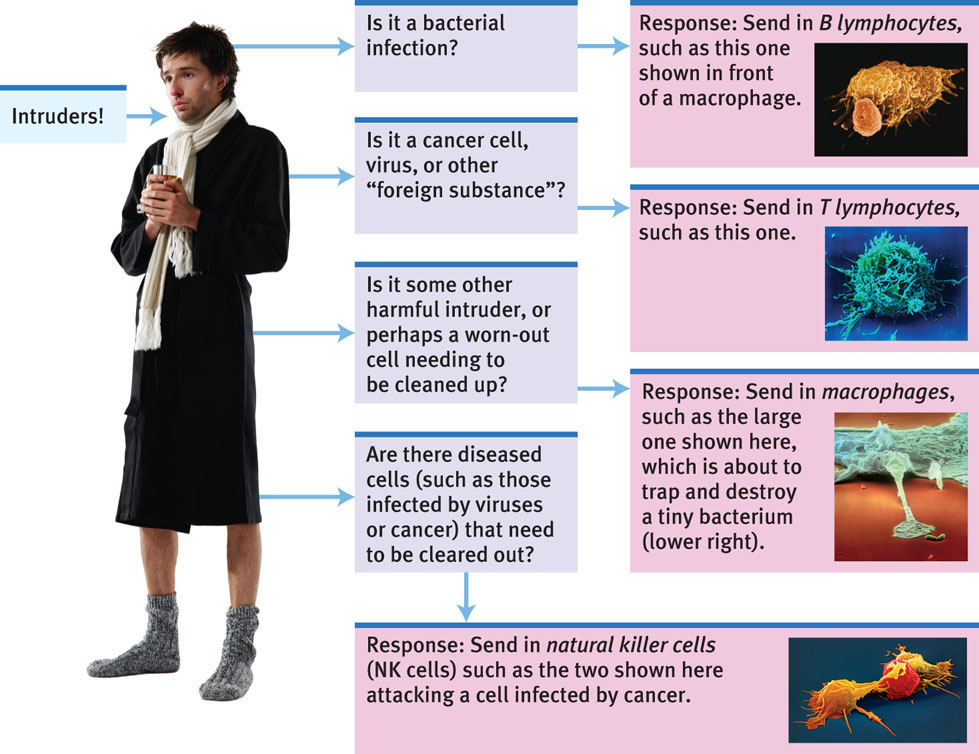

Your immune system resembles a complex security system. When it functions properly, it keeps you healthy by capturing and destroying bacteria, viruses, and other invaders. Four types of cells carry out these search-and-destroy missions (FIGURE 10.3). Two are types of white blood cells, called lymphocytes. B lymphocytes release antibodies that fight bacterial infections. T lymphocytes attack cancer cells, viruses, and foreign substances—even “good” ones, such as transplanted organs. The third cell type is the macrophage (“big eater”), which identifies, traps, and destroys harmful invaders and worn-out cells. And, finally, the natural killer cells (NK cells) attack diseased cells (such as those infected by viruses or cancer).

CNRI/Science Source

NIBSC/Science Source

Lennart Nilsson/Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH

Eye of Science/Science Source

287

Your age, nutrition, genetics, body temperature, and stress all influence your immune system’s activity. When your immune system doesn’t function properly, it can err in two directions:

- Responding too strongly, it may attack the body’s own tissues, causing some forms of arthritis or an allergic reaction. Women have stronger immune systems, making them less likely than men to get infections. But this very strength also puts women at higher risk for self-attacking diseases, such as lupus and multiple sclerosis (Nussinovitch & Schoenfeld, 2012; Schwartzman-Morris & Putterman, 2012).

- Underreacting, the immune system may allow a bacterial infection to flare, a dormant herpes virus to erupt, or cancer cells to multiply. Surgeons may deliberately suppress the patient’s immune system to protect transplanted organs (viewed as foreign invaders).

A flood of stress hormones can also suppress the immune system. In laboratories, immune suppression appears when animals are stressed by physical restraints, unavoidable electric shocks, noise, crowding, cold water, social defeat, or separation from their mothers (Maier et al., 1994). In one such study, monkeys were housed with new roommates—three or four new monkeys—each month for six months (Cohen et al., 1992). If you know the stress of adjusting to even one new roommate, you can imagine how trying it would be to repeat this experience monthly. By the experiment’s end, the socially stressed monkeys’ immune systems were weaker than those of other monkeys left in stable groups.

Human immune systems react similarly. Two examples:

- Surgical wounds heal more slowly in stressed people. In one experiment, two groups of dental students received punch wounds (small holes punched in the skin). Punch-wound healing was 40 percent slower in the group wounded three days before a major exam than in the group wounded during summer vacation (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1998).

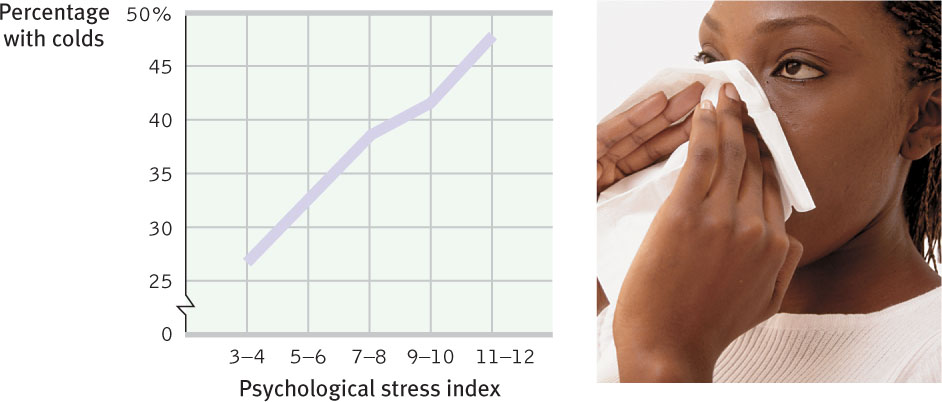

- Stressed people develop colds more readily. Researchers dropped a cold virus in the noses of people with high and low life-stress scores (FIGURE 10.4). Among those living stress-filled lives, 47 percent developed colds. Among those living relatively free of stress, only 27 percent did (Cohen et al., 1999, 2003, 2006a,b).

- Low stress may increase the effectiveness of vaccinations. Nurses gave older adults a flu vaccine and then measured how well their bodies fought off bacteria and viruses. The vaccine was most effective among older adults who had a healthy body weight and experienced low stress (Segerstrom et al., 2012).

288

The stress effect on immunity makes sense. It takes energy to track down invaders, produce swelling, and maintain fevers (Maier et al., 1994). Stress hormones drain this energy away from the disease-fighting white blood cells. When you are ill, your body demands less activity and more sleep, in part to cut back on the energy your muscles usually use. Stress does the opposite. During an aroused fight-or-flight reaction, your stress responses draw energy away from your disease-fighting immune system and send it to your muscles and brain (see Figure 9.13 in Chapter 9). This competing energy need leaves you more open to illness.

The bottom line: Stress does not make us sick. But it does reduce our immune system’s ability to function, and that leaves us less able to fight infection.

Let’s look now at how stress might affect AIDS, cancer, and heart disease.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 10.2

________ focuses on mind-body interactions, including the effects of psychological, neural, and endocrine functioning on the immune system and overall health.

Psychoneuroimmunology

Question 10.3

What general effect does stress have on our overall health?

Stress tends to reduce our immune system’s ability to function properly, so that those who regularly experience higher stress also have a higher risk of physical illness.

Stress and AIDS

We know that stress suppresses immune system functioning. What does this mean for people suffering from AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome)? People with AIDS already have a damaged immune system. The name of the virus that triggers AIDS tells us that. “HIV” stands for human immunodeficiency virus.

Stress can’t give people AIDS. But could stress and negative emotions speed the transition from HIV infection to AIDS in someone already infected? Might stress predict a faster decline in those with AIDS? An analysis of 33,252 participants from around the world suggests the answer to both questions is Yes (Chida & Vedhara, 2009). The greater the stress that HIV-infected people experience, the faster their disease progresses.

Could reducing stress help control AIDS? The answer again appears to be Yes. Although drug treatments are more effective, educational programs, grief support groups, talk therapy, relaxation training, and exercise programs that reduce distress have all had good results for HIV-positive people (Baum & Posluszny, 1999; McCain et al., 2008; Schneiderman, 1999).

Stress and Cancer

Stress does not create cancer cells. But in a healthy, functioning immune system, lymphocytes, macrophages, and NK cells search out and destroy cancer cells and cancer-damaged cells. If stress weakens the immune system, might this weaken a person’s ability to fight off cancer? To find out, researchers implanted tumor cells in rodents. Next, they exposed some of the rodents to uncontrollable stress (for example, inescapable restraint). Compared with their unstressed counterparts, the stressed rodents had weaker immune function, lower body weight, and grew larger tumors (Frick et al., 2009).

Does this stress-cancer link apply to humans? The results are mixed. Some studies have found that people are at increased risk for cancer within a year after experiencing depression, helplessness, or grief. In one large study, the risk of colon cancer was 5.5 times greater among people with a history of workplace stress than among those who did not report such problems. The difference was not due to group differences in age, smoking, drinking, or physical characteristics (Courtney et al., 1993). Other studies, however, have found no link between stress and a risk of cancer in humans (Edelman & Kidman, 1997; Fox, 1998; Petticrew et al., 1999, 2002). Concentration camp survivors and former prisoners of war, for example, do not have elevated cancer rates. So this research story is still being written.

289

There is a danger in hyping reports on attitudes and cancer. Can you imagine how a woman dying of breast cancer might react to a report on the effects of stress on the speed of decline in cancer patients? She could wrongly blame herself for her illness. (“If only I had been more expressive, relaxed, and hopeful.”) Her loved ones could become haunted by the notion that they caused her illness. (“If only I had been less stressful to my mom.”)

“I didn’t give myself cancer.”

Mayor Barbara Boggs Sigmund (1939–1990), Princeton, New Jersey

It’s important enough to repeat: Stress does not create cancer cells. At worst, stress may affect their growth by weakening the body’s natural defenses against multiplying cancer cells (Antoni & Lutgendorf, 2007). Although a relaxed, hopeful state may enhance these defenses, we should be aware of the thin line that divides science from wishful thinking. The powerful biological processes at work in advanced cancer or AIDS are not likely to be completely derailed by avoiding stress or maintaining a relaxed but determined spirit (Anderson, 2002; Kessler et al., 1991).

Stress and Heart Disease

10-4 How does stress increase coronary heart disease risk?

Depart from reality for a moment. In this new world, you wake up each day, eat your breakfast, and check the news. Political coverage buzzes, local events snap up airtime, and your favorite sports team occasionally wins. But there is a fourth story: Four 747 jumbo jet airlines crashed yesterday and all 1642 passengers died. You finish your breakfast, grab your books, and head to class. It’s just an average day.

Replace airline crashes with coronary heart disease, the United States’ leading cause of death, and you have re-entered reality. About 600,000 Americans die annually from heart disease (CDC, 2013). Heart disease occurs when the blood vessels that nourish the heart muscle gradually close. High blood pressure and a family history of the disease increase the risk. So do smoking, obesity, a high-fat diet, physical inactivity, and a high cholesterol level.

Stress and personality also play a big role in heart disease. The more psychological trauma people experience, the more their bodies generate inflammation, which is associated with heart and other health problems (O’Donovan et al., 2012). Plucking a hair and measuring its level of cortisol (a stress hormone) can help predict whether a person will have a future heart attack (Pereg et al., 2011).

In some classic studies, Meyer Friedman, Ray Rosenman, and their colleagues measured the blood cholesterol level and clotting speed of 40 U.S. male tax accountants during unstressful and stressful times of year (Friedman & Rosenman, 1974; Friedman & Ulmer, 1984). From January through March, the accountants showed normal results. But as the accountants began scrambling to finish their clients’ tax returns before the April 15 filing deadline, their cholesterol and clotting measures rose to dangerous levels. In May and June, with the deadline passed, their health measures returned to normal. Stress predicted heart attack risk for the accountants, with rates going up during their most stressful times.

A more recent study showed similar effects, with Americans’ blood pressure increasing two months after the 9/11 World Trade Center attacks compared with the two months preceding the attacks (Gerin et al., 2005). Blood pressure also rises as students approach everyday academic stressors (Conley & Lehman, 2012). So, are some of us at high risk of stress-related coronary disease? To answer this question, the researchers who studied the tax accountants launched a classic nine-year study of more than 3000 healthy men, aged 35 to 59.

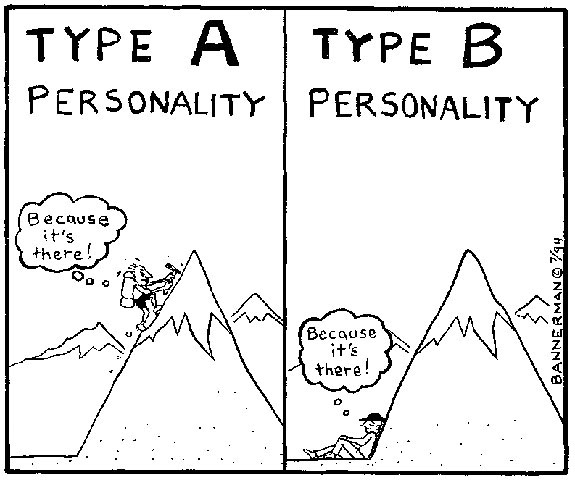

At the start of the study, the researchers interviewed each man for 15 minutes, noting his work and eating habits, manner of talking, and other behavioral patterns. Some men reacted strongly. These men, whom they labeled Type A, were competitive, hard-driving, impatient, time-conscious, super-motivated, verbally aggressive, and easily angered. The roughly equal number who were more easygoing they called Type B. Which group do you suppose turned out to be the most coronary-prone?

Nine years later, 257 men in the study had suffered heart attacks, and 69 percent of them were Type A. Moreover, not one of the “pure” Type Bs—the most mellow and laid-back of their group—had suffered a heart attack.

290

As often happens in science, this exciting discovery provoked enormous public interest. But after that initial honeymoon period, researchers wanted to know more. Was the finding reliable? If so, what exactly is so toxic about the Type A profile: Time-consciousness? Competitiveness? Anger? Further research revealed the answer. Type A’s toxic core is negative emotions—especially anger (Smith, 2006; Williams, 1993). Type A individuals are more often “combat ready.” When these people are threatened or challenged by a stressor, they react aggressively. As their often active sympathetic nervous system redistributes bloodflow to the muscles, it pulls blood away from internal organs. One of these internal organs, the liver, which normally removes cholesterol and fat from the blood, can’t do its job. Excess cholesterol and fat continue to circulate in the blood and are deposited around the heart. Further stress—sometimes conflicts brought on by their own traits—may trigger altered heart rhythms. In people with weakened hearts, this altered pattern can cause sudden death (Kamarck & Jennings, 1991). Our heart and mind interact.

“The fire you kindle for your enemy often burns you more than him.”

Chinese proverb

Hundreds of other studies of young and middle-aged men and women have confirmed that people who react with anger over little things are the most coronary-prone (Chida & Hamer, 2008; Chida & Steptoe, 2009). One study followed 13,000 middle-aged people for five years. Among those with normal blood pressure, people who had scored high on anger were three times more likely to have had heart attacks, even after researchers controlled for smoking and weight (Williams et al., 2000). Another study followed 1055 male medical students over an average of 36 years. Those who had reported being hot-tempered were five times more likely to have had a heart attack by age 55 (Chang et al., 2002). As others have noted, rage “seems to lash back and strike us in the heart muscle” (Spielberger & London, 1982).

In recent years, another personality type has interested stress and heart disease researchers. For these Type D individuals, the negative emotion they experience during social interactions is mainly distress (Denollet, 2005; Denollet et al., 1996). Type A individuals direct their negative emotion toward dominating others. Type D people suppress their negative emotion to avoid social disapproval. In one analysis of 12 studies, Type D personality significantly increased risk for mortality and nonfatal heart attack (Grande et al., 2012).

Depression, too, can be lethal, as the evidence from 57 studies has shown (Wulsin et al., 1999). In one study, people with high scores for depression were four times more likely than their low-scoring counterparts to develop further heart problems (Frasure-Smith & Lesperance, 2005). In a British study that followed 61,349 people over three to six years, depression predicted risk of death as well as did smoking (Mykletun et al., 2009). It is still unclear why depression poses such a serious risk for heart disease, but this much seems clear: Depression is disheartening.

So, in many ways stress can affect our health (Figure 10.5). Our stress-related susceptibility to disease is a price we pay for the benefits of stress. Stress enriches our lives. It arouses and motivates us. An unstressed life would not be challenging or productive.

291