Coping With Stress

10-5 What are two basic ways that people cope with stress?

Stressors are unavoidable. That’s the reality we live with. One way we can develop our strengths and protect our health is to learn better ways to cope with our stress.

Stressors are unavoidable. That’s the reality we live with. One way we can develop our strengths and protect our health is to learn better ways to cope with our stress.

We need to find new ways to feel, think, and act when we are dealing with stressors. We address some stressors directly, with problem-focused coping. For example, if our impatience leads to a family fight, we may go directly to that family member to work things out. We tend to use problem-focused strategies when we feel a sense of control over a situation and think we can change the circumstances, or at least change ourselves to deal with the circumstances more capably.

We turn to emotion-focused coping when we cannot—or believe we cannot—change a situation. If, despite our best efforts, we cannot get along with a family member, we may search for relief from stress by confiding in friends and reaching out for support and comfort.

Emotion-focused strategies can move us toward better long-term health, as when we attempt to gain emotional distance from a damaging relationship or keep busy with hobbies to avoid thinking about an old addiction. Emotion-focused strategies can also be maladaptive, however, as when students worried about not keeping up with the reading in class go out to party or play video games to get it off their mind. Sometimes a problem-focused strategy (catching up with the reading) will reduce stress more effectively and promote long-term health and satisfaction.

Our success in coping depends on several factors. Let’s look at four of them: personal control, an optimistic outlook, social support, and finding meaning in life’s ups and downs.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 10.4

To cope with stress, we tend to use _______-focused (emotion/problem) strategies when we feel in control of our world. When we believe we cannot change a situation, we may try to relieve stress with _______-focused (emotion/problem) strategies.

To cope with stress, we tend to use _______-focused (emotion/problem) strategies when we feel in control of our world. When we believe we cannot change a situation, we may try to relieve stress with _______-focused (emotion/problem) strategies.

problem; emotion

Personal Control, Health, and Well-Being

10-6 How does our sense of control influence stress and health?

Personal control refers to how much we perceive having control over our environment. Psychologists study the effect of personal control (or any personality factor) in two ways:

- They correlate people’s feelings of control with their behaviors and achievements.

- They experiment, by raising or lowering people’s sense of control and noting the effects.

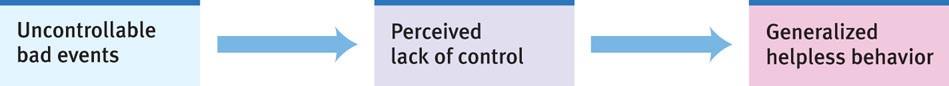

At times, we all feel helpless, hopeless, and depressed after experiencing a series of bad events beyond our control. For some animals and people, a series of uncontrollable events creates a state of learned helplessness, with feelings of passive resignation (FIGURE 10.6). In one series of experiments, dogs were strapped in a harness and given repeated shocks, with no opportunity to avoid them (Seligman & Maier, 1967). When later placed in another situation where they could escape the punishment by simply leaping a hurdle, the dogs cowered as if without hope. Other dogs that had been able to escape the first shocks reacted differently. They had learned they were in control, and in the new situation they easily escaped the shocks (Seligman & Maier, 1967). In other experiments, people have shown similar patterns of learned helplessness (Abramson et al., 1978, 1989; Seligman, 1975).

Learned helplessness is a dramatic form of loss of control, but we’ve all felt a loss of control at times. Our health can suffer as our level of stress hormones (such as cortisol) rise, our blood pressure increases, and our immune responses weaken (Rodin, 1986; Sapolsky, 2005). One study found these effects among nurses, who reported their workload and their level of personal control on the job. The greater their workload, the higher their cortisol level and blood pressure—but only among nurses who reported little control over their environment (Fox et al., 1993). Stress effects have also been observed among captive animals. Those in captivity are more prone to disease than their wild counterparts, which have more control over their lives (Roberts, 1988). Similar effects are found when humans are crowded together in high-density neighborhoods, prisons, and even college dorms (Fleming et al., 1987; Fuller et al., 1993; Ostfeld et al., 1987). Feelings of control drop, and stress hormone levels and blood pressure rise.

Proposals to improve health and morale by increasing control have included (Humphrey et al., 2007; Ruback et al., 1986; Warburton et al., 2006):

- Allowing prisoners to move chairs and control room lights and the TV.

- Having workers participate in decision making. Simply allowing people to personalize their workspace has been linked with higher (55 percent) engagement with their work (Krueger & Killham, 2006).

- Offering nursing home patients choices about their environment. In one famous study, 93 percent of nursing home patients who were encouraged to exert more control became more alert, active, and happy (Rodin, 1986).

“Perceived control is basic to human functioning,” concluded researcher Ellen Langer (1983, p. 291). “For the young and old alike,” she suggested, environments should enhance people’s sense of control over their world. No wonder mobile devices and DVRs, which enhance our control of the content and timing of our entertainment, are so popular.

Google incorporates these principles effectively. Each week, Google employees can spend 20 percent of their working time on projects they find personally interesting. This Innovation Time Off program increases employees’ personal control over their work environment, and it has paid off. Gmail was developed this way.

The power of having personal control also shows up at national levels. People thrive when they live in conditions of personal freedom and empowerment. For example, citizens of stable democracies report higher levels of happiness (Inglehart et al., 2008).

So, some freedom and control are better than none. But does ever-increasing choice breed ever-happier lives? Some researchers have suggested that today’s Western cultures offer an “excess of freedom”—too many choices. The result can be decreased life satisfaction, increased depression, or even behavior paralysis (Schwartz, 2000, 2004). In one study, people offered a choice of one of 30 brands of jam or chocolate were less satisfied with their decision than were others who had chosen from only 6 options (Iyengar & Lepper, 2000). This tyranny of choice brings information overload and a greater likelihood that we will feel regret over some of the things we left behind. (Do you, too, ever waste time agonizing over too many choices?)

Who Controls Your Life?

Latitude Stock/Brian Fairbrother/Getty

Do you believe that your life is out of control? That the world is run by a few powerful people? That getting a good job depends mainly on being in the right place at the right time? Or do you more strongly believe that you control your own fate? That each of us can influence our government’s decisions? That being a success is a matter of hard work?

Hundreds of studies have compared people who differ in their perceptions of control:

- Those who have an external locus of control believe that chance or outside forces control their fate.

- Those who have an internal locus of control believe they control their own destiny.

Does it matter which view we hold? In study after study comparing people with these two viewpoints, the “internals” have achieved more in school and work, acted more independently, enjoyed better health, and felt less depressed (Lefcourt, 1982; Ng et al., 2006). In one long-term study of more than 7500 people, those who had expressed a more internal locus of control at age 10 exhibited less obesity, lower blood pressure, and less distress at age 30 (Gale et al., 2008).

Another way to say that we believe we are in control of our own life is to say we have free will, or that we can control our own willpower. Studies show that people who believe in their freedom learn better, perform better at work, and behave more helpfully (Job et al., 2010; Stillman et al., 2010).

So we differ in our perceptions of whether we have control over our world. Why? Compared with their parents’ generation, more young Americans now endorse an external locus of control (Twenge et al., 2004). This shift may help explain an associated increase in rates of depression and other psychological disorders (Twenge et al., 2010).

Coping With Stress by Boosting Self-Control

Google trusted its belief in the power of personal control, and the company and its employees reaped the benefits. Could we reap similar benefits by actively managing our own behavior? One place to start might be increasing our self-control—the ability to control impulses and delay immediate gratification. Strengthening our self-control may not pay off with a Gmail invention, but self-control has been linked to health and well-being (Moffitt et al., 2011; Tangney et al., 2004). People with more self-control earn higher grades, accumulate more wealth, enjoy better mental health, and have stronger relationships. In one study that followed eighth-graders over a school year, better self-control was more than twice as important as intelligence score in predicting academic success (Duckworth & Seligman, 2005).

Self-control is constantly changing—from day to day, hour to hour, and even minute to minute. We can compare self-control to a muscle: It weakens after use, recovers after rest, and grows stronger with exercise (Baumeister & Exline, 2000; Hagger et al., 2010; Vohs & Baumeister, 2011).

When you use your self-control, you have less of it available to use when you need it later (Gailliot et al., 2007). In one experiment, hungry people who had resisted eating tempting chocolate chip cookies abandoned a frustrating task sooner than people who had not resisted the cookies (Baumeister et al., 1998). When people feel provoked, those who have used up their self-control energy have acted more aggressively toward strangers and intimate partners (DeWall et al., 2007). In one experiment, frustrated participants with low self-control energy stuck more pins into a voodoo doll that represented their romantic partner. Participants whose self-control energy was left intact used fewer pins (Finkel et al., 2012).

Exercising self-control uses up the blood sugar and brain energy needed for mental focus (Inzlicht & Gutsell, 2007). Some people can spend their self-control energy on losing weight. Others may do so to stop smoking. But given our limited reservoir of self-control, few can do both simultaneously. (It often pays to work on one thing at a time.)

What, then, might be the effect of deliberately boosting people’s blood sugar when their self-control energy has been used up? In one study, energy-boosting sugar (in a naturally rather than an artificially sweetened lemonade) had a sweet effect. It strengthened people’s conscious thought processes and reduced their financial impulsiveness and aggression (Denson et al., 2010; Masicampo & Baumeister, 2008; Wang & Dvorak, 2010). Even dogs experiencing self-control energy loss seemed to bounce back after this sweet treatment (Miller et al., 2010).

Decreased mental energy after exercising self-control is a short-term effect. The long-term effect of exercising self-control is increased self-control, much as a hard physical workout leaves you temporarily tired out, but stronger in the long term. Strengthened self-control improves people’s performance on laboratory tasks as well as their self-management of eating, drinking, smoking, and household chores (Oaten & Cheng, 2006a,b).

The point to remember: Develop self-discipline in one area of your life, and your strengthened self-control may spill over into other areas as well, making for a less stressed life.

Is the Glass Half Full or Half Empty?

10-7 How do optimists and pessimists differ, and why does our outlook on life matter?

Another part of coping with stress is our outlook—how we perceive the world. Optimists agree with statements such as, “In uncertain times, I usually expect the best” (Scheier & Carver, 1992). Optimists expect to have control, to cope well with stressful events, and to enjoy good health. Pessimists don’t share these expectations. They expect things to go badly (Aspinwall & Tedeschi, 2010; Carver et al., 2010; Rasmussen et al., 2009). And when bad things happen, pessimists knew it all along. They lacked the necessary skills (“I can’t do this”). The situation prevented them from doing well (“There is nothing I can do about it”). They expected the worst and their expectations were fulfilled.

Optimism, like a feeling of personal control, pays off. Optimists respond to stress with smaller increases in blood pressure, and they recover more quickly from heart bypass surgery. And during the stressful first few weeks of classes, U.S. law school students who were optimistic (“It’s unlikely that I will fail”) enjoyed better moods and stronger immune systems (Segerstrom et al., 1998). When American dating couples wrestle with conflicts, optimists and their partners see each other as engaging constructively. They tend to feel more supported and satisfied with the resolution and with their relationship (Srivastava et al., 2006). Optimism also predicts well-being and success elsewhere, including China and Japan (Qin & Piao, 2011).

Is an optimistic outlook related to living a longer life? Possibly. One research team followed 941 Dutch people, aged 65 to 85, for nearly a decade (Giltay et al., 2004, 2007). They split the sample into four groups according to their optimism scores. Only 30 percent of those with the highest optimism died during the study, as did 57 percent of those with the lowest optimism.

The optimism–long-life correlation also appeared in a famous study of 180 American Catholic nuns. At about 22 years of age, each of these women had written a brief autobiography. In the decades that followed, they lived similar lifestyles. Those who had expressed happiness, love, and other positive feelings in their autobiographies lived an average of seven years longer than did the more negative nuns (Danner et al., 2001). By age 80, only 24 percent of the most positive-spirited had died, compared with 54 percent of those expressing few positive emotions.

Optimism runs in families, so some people truly are born with a sunny, hopeful outlook. With identical twins, if one is optimistic, the other often will be as well (Mosing et al., 2009). One genetic marker of optimism is a gene that enhances the social-bonding hormone oxytocin (Saphire-Bernstein et al., 2011).

Positive thinking pays dividends, but so does a dash of realism (Schneider, 2001). Realistic anxiety over possible future failures—worrying about being able to pay a bill on time, or fearing you will do badly on an exam—can cause you to try extra hard to avoid failure (Goodhart, 1986; Norem, 2001; Showers, 1992). Students concerned about failing an upcoming exam may study more, and therefore outperform equally able but more confident peers. This may help explain the impressive academic achievements of some Asian-American students. Compared with European-Americans, these students express somewhat greater pessimism (Chang, 2001). Success requires enough optimism to provide hope and enough pessimism to keep you on your toes.

“God grant us the serenity to accept the things we cannot change, courage to change the things we can, and wisdom to know the difference.”

Alcoholics Anonymous Serenity Prayer (attributed to Reinhold Niebuhr)

Excessive optimism can blind us to real risks (Weinstein, 1980, 1982, 1996). Most college students display an unrealistic optimism. They view themselves as less likely than their average classmate to develop drinking problems, drop out of school, or have a heart attack. Most older adolescents see themselves as much less likely than their peers to contract the AIDS virus (Abrams, 1991; Gold, 2006) or to develop skin cancer. Many credit-card users choose cards with low fees and high interest, causing them to pay more because they are unrealistically optimistic that they will always pay off the monthly balance (Yang et al., 2006). Blinded by optimism, people young and old echo the statement famed basketball player Magic Johnson made (1993) after contracting HIV: “I didn’t think it could happen to me.”

Social Support

10-8 How do social support and finding meaning in life influence health?

Which of these factors has the strongest association with poor health: smoking 15 cigarettes daily, being obese, being inactive, or lacking strong social connections? This is a trick question, because each factor has a roughly similar impact (Cacioppo & Patrick, 2008). That’s right! Social support—feeling liked and encouraged by intimate friends and family—promotes both happiness and health. It helps you cope with stress. Not having this support can affect your health as much as smoking nearly a pack per day.

Seven massive investigations that followed thousands of people over several years reached similar conclusions. People supported by close relationships are less likely to die early (Uchino, 2009). These relationships may be with friends, family, fellow workers, members of our faith community, or some other support group. Even pets can help us cope with stress. (See Close-Up: Pets Are Friends, Too.)

Happy marriages bathe us in social support. People in low-conflict marriages live longer, healthier lives than the unmarried (Kaplan & Kronick, 2006; Wilson & Oswald, 2002). This correlation holds regardless of age, sex, race, and income (National Center for Health Statistics, 2004). One seven-decade-long study found that at age 50, healthy aging is better predicted by a good marriage than by a low cholesterol level (Vaillant, 2002). On the flip side, divorce is a predictor of poor health. In one analysis of 32 studies involving more than 6.5 million people, divorced people were 23 percent more likely to die early (Sbarra et al., 2011).

C L O S E - U P

Pets Are Friends, TooHave you ever wished for a friend who would love you just as you are? One who would never judge you? Who would be there for you, no matter your mood? For many tens of millions of people that friend exists, and it is a loyal dog or a friendly cat.

Many people describe their pet as a beloved family member who helps them feel calm, happy, and valued. Can pets also help people handle stress? If so, might pets have healing power? Karen Allen has reported that the answers are Yes and Yes. For example, women’s blood pressure rises as they struggle with challenging math problems in the presence of a best friend or even a spouse, but it rises much less in the presence of their dog (Allen, 2003). Pets increase the odds of survival after a heart attack. They relieve depression among AIDS patients. And they lower the level of fatty acids in the blood that increase the risk of heart disease.

So, would pets be good medicine for people who do not have pets? To find out, Allen experimented. The participants were a group of stockbrokers. They all lived alone, described their work as stressful, and had high blood pressure. She randomly selected half to adopt an animal shelter cat or dog. Did these new companions help their owners handle stress better? Indeed they did. When later facing stress, all participants experienced higher blood pressure. But among the new pet owners, the increase was only half as high as the increases in the no-pet group. The effect was greatest for pet owners with few social contacts or friends. Allen’s conclusion: For lowering blood pressure, pets are no substitute for effective drugs and exercise. But for those who enjoy animals, and especially for those who live alone, they are a healthy pleasure.

Social support helps us fight illness in at least two ways. First, it calms our cardiovascular system, which lowers blood pressure and stress hormone levels (Uchino et al., 1996, 1999). To see if social support might calm people’s response to threats, one research team subjected happily married women, while lying in an fMRI machine, to the threat of electric shock to an ankle (Coan et al., 2006). During the experiment, some women held their husband’s hand. Others held a stranger’s hand or no hand at all. While awaiting the occasional shocks, the women’s brains reacted differently. Those who held their husband’s hand had less activity in threat-responsive areas. This soothing benefit was greatest for women reporting the highest-quality marriages. A follow-up experiment suggested that simply viewing a supportive romantic partner’s picture was enough to reduce painful discomfort (Master et al., 2009). One study of women with ovarian cancer suggests that social support may slow the progression of cancer. Researchers found that women with the highest levels of social support had the lowest levels of a stress hormone linked to cancer progression.

Social support helps us cope with stress in a second way. It helps us fight illness by fostering stronger immune functioning. We have seen that stress puts us at risk for disease because it steals disease-fighting energy from our immune system. Social support seems to reboot our immune system. In one series of studies, research volunteers with strong support systems showed greater resistance to cold viruses (Cohen et al., 1997, 2004). After inhaling nose drops loaded with a cold virus, two groups of healthy volunteers were isolated and observed for five days. (The volunteers each received $800 to endure this experience.) The researchers then took a cold hard look at the results. After controlling for age, race, sex, smoking, and other health habits, they found that people with close social ties in their everyday lives were least likely to catch a cold. If they did catch one, they produced less mucus. The effect of social ties is nothing to sneeze at!

When we are trying to cope with stressors, social ties can tug us toward or away from our goal. Are you trying to exercise more, drink less, quit smoking, or eat better? If so, think about whether your social network can help or hinder you. That social net covers not only the people you know but friends of your friends, and friends of their friends. That’s three degrees of separation between you and the most remote people. Within that network, others can influence your thoughts, feelings, and actions without your awareness (Christakis & Fowler, 2009). Obesity, for example, spreads within networks, and it is not merely a reflection of our tendency to seek out similar others. Three degrees of separation seems to be the limit for this type of social influence.

Finding Meaning

Catastrophes and significant life changes can leave us confused and distressed as we try to make sense of what happened. At such times, an important part of coping with stress is finding meaning in life—some redeeming purpose in our suffering (Taylor, 1983). Unemployment is very threatening, but it may free up time to spend with children. The loss of a loved one may force us to expand our social network. A heart attack may trigger a shift toward healthy, active living. Some have argued that the search for meaning is fundamental. We constantly seek to maintain meaning when our expectations are not met (Heine el al., 2006). As psychiatrist Viktor Frankl (1962), who had been imprisoned in a Nazi concentration camp, observed, “Life is never made unbearable by circumstances, but only by lack of meaning and purpose.”

Close relationships offer an opportunity for “open heart therapy”—a chance to confide painful feelings and sort things out (Frattaroli, 2006). Talking about things that push our buttons may arouse us in the short term. But in the long term, it calms us by reducing activity in our limbic system (Lieberman et al., 2007; Mendolia & Kleck, 1993). Talking or writing about our experiences helps us make sense of our stress and find meaning in it (Esterling et al., 1999). In one study, 33 Holocaust survivors spent two hours recalling their experiences, many in intimate detail never before disclosed (Pennebaker et al., 1989). In the weeks following, most watched a tape of their recollections and showed it to family and friends. Those who were most self-disclosing had the most improved health 14 months later. Confiding is good for the body and the soul. Another study surveyed surviving spouses of people who had committed suicide or died in car accidents. Those who bore their grief alone had more health problems than those who could express it openly (Pennebaker & O’Heeron, 1984).

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 10.5

Some research finds that people with companionable pets are less likely than those without pets to visit their doctors after stressful events (Siegel, 1990). How can the health benefits from social support shed light on this finding?

Some research finds that people with companionable pets are less likely than those without pets to visit their doctors after stressful events (Siegel, 1990). How can the health benefits from social support shed light on this finding?

Feeling social support—even from a pet—might calm people and lead to lower levels of stress hormones and blood pressure.