Happiness

10-12 What are the causes and consequences of happiness?

In The How of Happiness, psychologist Sonja Lyubomirsky (2008) tells the true story of Randy. By any measure, Randy lived a hard life. His dad and best friend died by suicide. Growing up, his mother’s boyfriend treated him poorly. Randy’s own first marriage was troubled. His wife was unfaithful, and they divorced. Despite these setbacks, Randy is a happy person whose endless optimism can light up a room. He remarried and enjoys his role as stepfather to three boys. He also finds his work life to be rewarding. Randy says he survived his life stressors by seeing the “silver lining in the cloud.”

In The How of Happiness, psychologist Sonja Lyubomirsky (2008) tells the true story of Randy. By any measure, Randy lived a hard life. His dad and best friend died by suicide. Growing up, his mother’s boyfriend treated him poorly. Randy’s own first marriage was troubled. His wife was unfaithful, and they divorced. Despite these setbacks, Randy is a happy person whose endless optimism can light up a room. He remarried and enjoys his role as stepfather to three boys. He also finds his work life to be rewarding. Randy says he survived his life stressors by seeing the “silver lining in the cloud.”

Bouncing back from serious losses, as Randy did, people may feel a stronger sense of self-esteem and a deeper sense of purpose. Tough challenges, especially early in life, can foster personal growth and emotional resilience (Landauer & Whiting, 1979).

Are you a person who makes everyone around you smile and laugh? Have you, like Randy, bounced back from serious challenges and become stronger because of it? Our state of happiness or unhappiness colors our thoughts and our actions. Happy people perceive the world as a safer place. They are more decisive and cooperate more easily. They live healthier and more energized and satisfied lives (Briñol et al., 2007; Liberman et al., 2009; Mauss et al., 2011). We all get gloomy sometimes. When that happens, life as a whole may seem depressing and meaningless. Let your mood brighten, and your thinking broadens and becomes more playful and creative (Baas et al., 2008; Forgas, 2008b; Fredrickson, 2006). Your relationships, your self-image, and your hopes for the future seem more promising.

This helps explain why college students’ happiness helps predict their life course. In one study, which surveyed thousands of U.S. college students in 1976 and restudied them at age 37, happy students had gone on to earn significantly more money than their less-happy-than-average peers (Diener et al., 2002). In another, the happiest 20-year-olds were not only more likely to marry, but also less likely to divorce (Stutzer & Frey, 2006).

Moreover—and this is one of psychology’s most consistent findings—when we feel happy we become more helpful. Psychologists call it the feel-good, do-good phenomenon (Salovey, 1990). Happiness doesn’t just feel good, it does good. In study after study, a mood-boosting experience (finding money, succeeding on a challenging task, recalling a happy event) has made people more likely to give money, pick up someone’s dropped papers, volunteer time, and do other good deeds.

The reverse is also true: Doing good promotes feeling good. One survey of more than 200,000 people in 136 countries found that, pretty much everywhere, people report feeling happier after spending money on others rather than themselves (Aknin et al., 2013). Some happiness coaches and instructors harness this force by asking their clients to perform a daily “random act of kindness” and to record how it made them feel.

William James was writing about the importance of happiness (“the secret motive for all [we] do”) as early as 1902. With the rise of positive psychology in the twenty-first century (Chapter 1), the study of happiness has become a main area of research. It is a key part of one of our big ideas in this text: Psychology explores human strengths as well as challenges. Part of happiness research is the study of subjective well-being—our feelings of happiness (sometimes defined as a high ratio of positive to negative feelings) or sense of satisfaction with life. This information, combined with objective measures of well-being, such as a person’s physical and economic condition, is helping us understand our quality-of-life judgments.

302

The Short Life of Emotional Ups and Downs

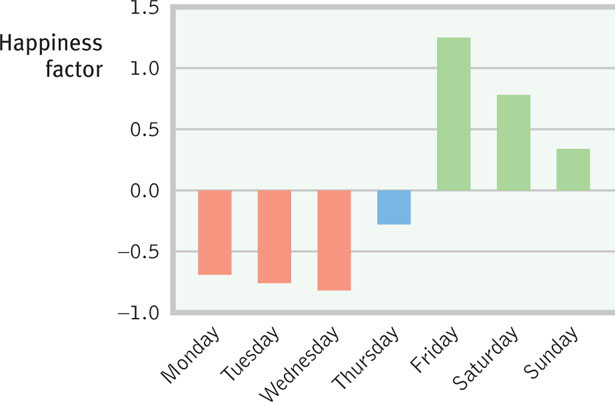

Are some days of the week happier than others? In what is surely psychology’s biggest-ever data sample, one social psychologist (Kramer, 2010—at my [DM] request and in cooperation with Facebook) did a naturalistic observation of emotion words in “billions” of status updates. After eliminating exceptional days, such as holidays, he tracked the frequency of positive and negative emotion words by day of the week. The days with the most positive moods? Friday and Saturday (FIGURE 10.12). A similar analysis of emotion-related words in 59 million Twitter messages found Friday to Sunday the week’s happiest days (Golder & Macy, 2011). For you, too?

Over the long run, our emotional ups and downs tend to balance out. This is true even over the course of the day. Positive emotion rises over the early to middle part of most days and then drops off (Kahneman et al., 2004; Watson, 2000). So, too, with day-to-day moods. A stressful event—an argument, a sick child, a car problem—triggers a bad mood. No surprise there. But by the next day, the gloom nearly always lifts (Affleck et al., 1994; Bolger et al., 1989; Stone & Neale, 1984). If anything, people tend to bounce back from a bad day to a better-than-usual good mood the following day. Even when negative events drag us down for longer periods, our bad mood usually ends. We may feel that our heart has broken during a romantic breakup, but eventually the wound heals.

Grief over the loss of a loved one or anxiety after a severe trauma can linger. But usually, even tragedy is not permanently depressing. People who have become blind or paralyzed have usually recovered near-normal levels of day-to-day happiness. So have those forced to go on kidney dialysis or to have permanent colostomies (Gerhart et al., 1994; Riis et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2009). Major disabilities have often left people somewhat less happy than the average person, yet considerably happier than able-bodied people with depression (Kübler et al., 2005; Lucas, 2007a,b; Schwartz & Estrin, 2004). “If you are a paraplegic,” explained psychologist Daniel Kahneman (2005), “you will gradually start thinking of other things, and the more time you spend thinking of other things, the less miserable you are going to be.” Contrary to what many people believe, even most patients “locked in” a motionless body do not indicate they want to die (Nizzi et al., 2012; Smith & Delargy, 2005; 2011). The surprising reality: We overestimate the duration of our emotions and underestimate our resilience—our ability to bounce back.

303

Wealth and Well-Being

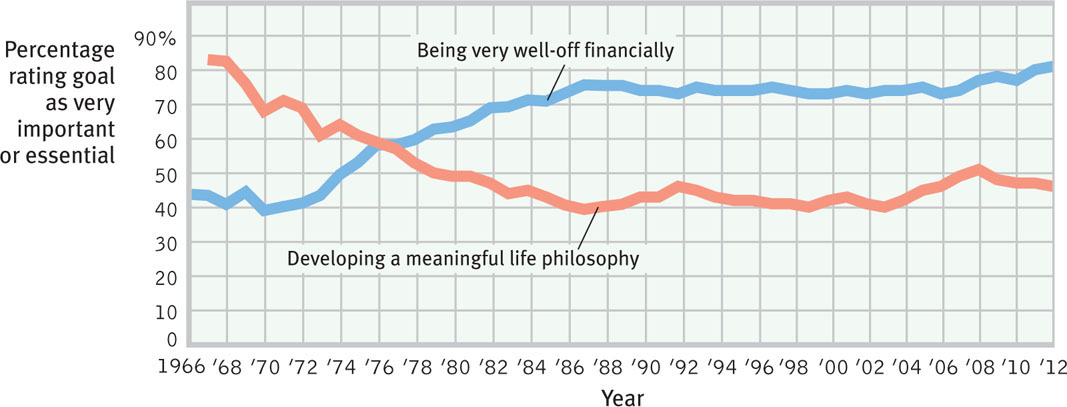

Would you be happier if you made more money? In a 2006 Gallup poll, 73 percent of Americans thought they would be. How important is “Being very well off financially”? Very important, say many entering U.S. collegians (FIGURE 10.13).

Having enough money to buy your way out of hunger and to enable a sense of control over your life does buy some happiness (Fischer & Boer, 2011). Money’s power to buy happiness also depends on your current income. A $1000 annual wage increase would do a lot more for the average person in a very poor country than for the average person in a very rich one. But once one has enough money for comfort and security, piling up more and more matters less and less.

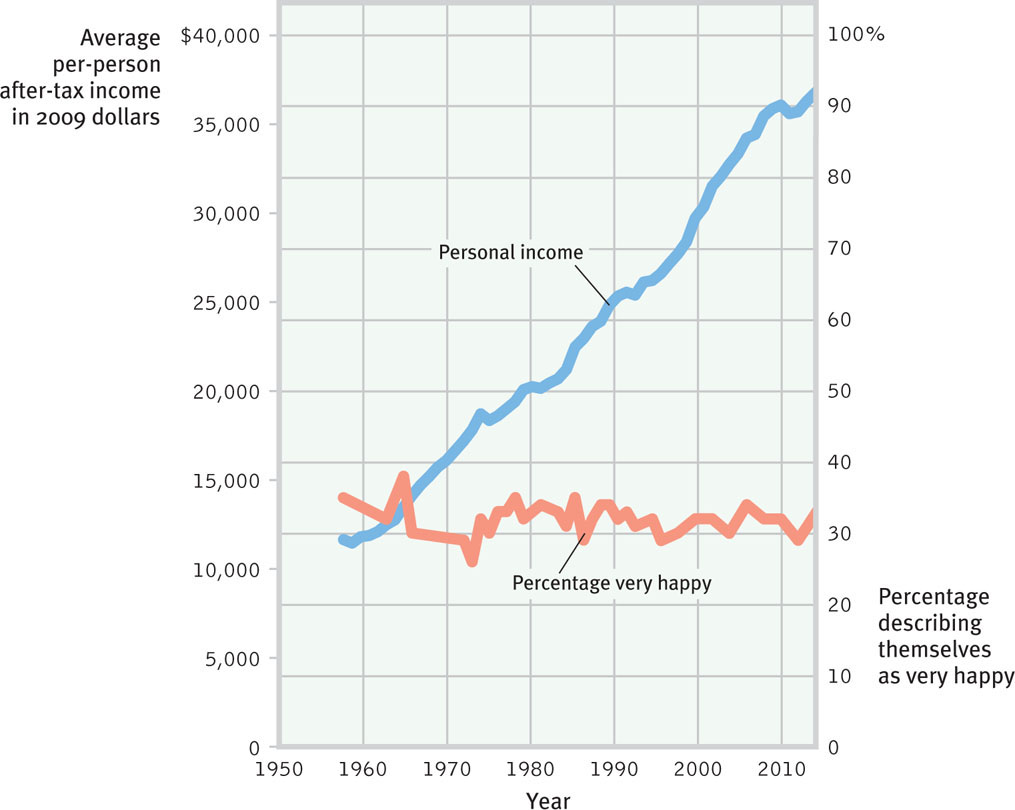

Consider: During the last four decades, the average U.S. citizen’s buying power almost tripled. Did this greater wealth—enabling twice as many cars per person, not to mention iPads, smart phones, and HDTVs—also buy more happiness? As FIGURE 10.14 shows, the average American, though certainly richer, is not a bit happier. In 1957, some 35 percent said they were “very happy,” as did slightly fewer—29 percent—in 2010. Ditto China, where living standards have risen but happiness has not (Davey & Rato, 2012; Easterlin et al., 2012). These findings lob a bombshell at modern materialism: Economic growth in wealthy countries has provided no apparent boost to morale or social well-being.

Why Can’t Money Buy More Happiness?

Why is it that, for those who are not poor, more and more money does not buy more and more happiness? More generally, why do our emotions seem to be attached to elastic bands that pull us back from highs or lows? Psychology has proposed two answers. Each suggests that happiness is relative.

My Happiness Is Relative to My Own Experience

We tend to judge new events by comparing them with our past experiences. Psychologists call this the adaptation-level phenomenon. Our past experiences act as neutral levels—sounds that seem neither loud nor soft, temperatures that seem neither hot nor cold, events that seem neither pleasant nor unpleasant. We then notice and react to variations up or down from these levels.

304

So, could we ever create a permanent social paradise? Probably not (Campbell, 1975; Di Tella et al., 2010). People who have experienced a recent windfall—from the lottery, an inheritance, or a surging economy—typically feel joy and satisfaction (Diener & Oishi, 2000; Gardner & Oswald, 2007). You would, too, if you woke up tomorrow with all your wishes granted. Wouldn’t you love to live in a world with no bills, no ills, perfect grades, and someone who loves you unreservedly? But after a time, you would gradually adapt, and you would adjust your neutral level to include these new experiences. Before long, you would again sometimes feel joy and satisfaction (when events exceed your expectations), sometimes feel let down (when they fall below), and sometimes feel neutral.

The point to remember: Feelings of satisfaction and dissatisfaction, success and failure are judgments we make about ourselves, based on our prior experience.

My Happiness Is Relative to Your Success

We are always comparing ourselves with others. And whether we feel good or bad depends on our perception of just how successful those others are (Lyubomirsky, 2001). We are slow-witted or clumsy only when others are smarter or more graceful. This sense that we are worse off than others with whom we compare ourselves is called relative deprivation.

When expectations soar above achievements, the result is disappointment. Thus, the middle- and upper-income people in a given country, who can compare themselves with the relatively poor, tend to be more satisfied with life than are their less-fortunate fellow citizens. Nevertheless, once people reach a moderate income level, further increases buy smaller increases in happiness. Why? Because as people climb the ladder of success, they mostly compare themselves with local peers who are at or above their current level (Gruder, 1977; Suls & Tesch, 1978; Zell & Alicke, 2010).

305

Just as comparing ourselves with those who are better off creates envy, so counting our blessings as we compare ourselves with those worse off boosts our contentment. In one study, University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee women considered others’ suffering (Dermer et al., 1979). They viewed vivid images of how grim life was in Milwaukee in 1900. They imagined and then wrote about various personal tragedies, such as being burned and disfigured. Later, the women expressed greater satisfaction with their own lives. Similarly, when mildly depressed people have read about someone who was even more depressed, they felt somewhat better (Gibbons, 1986). “I cried because I had no shoes,” states a Persian saying, “until I met a man who had no feet.”

Predictors of Happiness

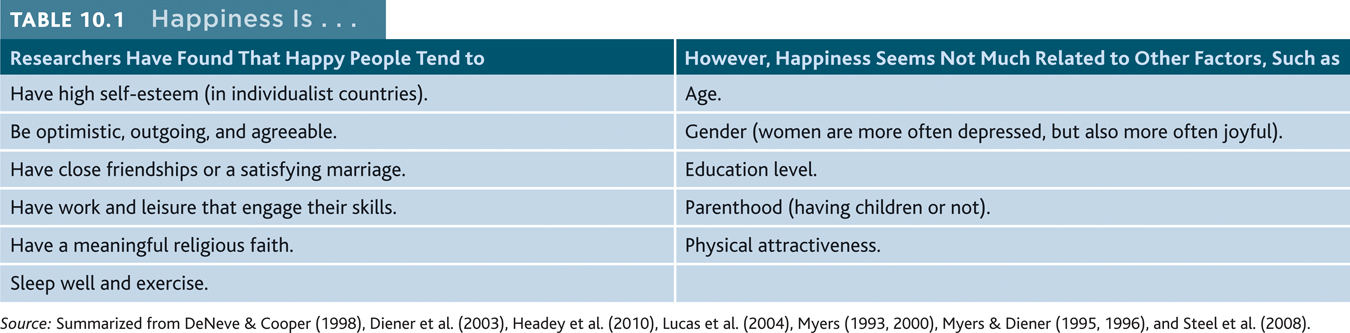

Happy people share many characteristics (TABLE 10.1). But what makes one person so filled with joy, day after day, and others so gloomy? Here, as in so many other areas, the answer is found in the interplay between nature and nurture.

Genes matter. Studies of hundreds of identical and fraternal twins indicate that heredity accounts for about 50 percent of the difference among people’s happiness ratings (Gigantesco et al., 2011; Lykken & Tellegen, 1996). Identical twins raised apart are often similarly happy.

But our personal history and our culture matter, too. On the personal level, as we saw earlier, our emotions tend to balance around a level defined by our experiences. On the cultural level, groups vary in the traits they value. Self-esteem matters more to Westerners, who value individualism. Social acceptance and harmony matter more to those in other cultures, such as in Japan, that stress family and community (Diener et al., 2003; Uchida & Kitayama, 2009).

Depending on our genes, our outlook, and our recent experiences, our happiness seems to vary around our “happiness set point.” Some of us seem to be ever upbeat; others, more negative. Even so, our satisfaction with life is not fixed (Fujita & Diener, 2005; Mroczek & Spiro, 2005). As researchers studying human strengths will tell you, happiness rises and falls, and we can control some of the factors that make us more or less happy (Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009). For more on this idea, see Close-Up: Want to Be Happier?

If we can enhance our happiness on an individual level, could we use happiness research to refocus our national priorities more on advancing psychological well-being? Many psychologists believe we could. More than 50 of them have joined together to propose ways in which nations might measure national well-being and assess the impacts of various public policies (Diener et al., 2006, 2009). Happy societies are not only prosperous but are also places where people trust one another, feel free, and enjoy close relationships (Oishi & Schimmack, 2010; Sachs, 2012). Thus, when debating such issues as economic inequality, tax rates, divorce laws, and health care, people’s psychological well-being should be a prime consideration. The Canadian, French, German, and British governments have each added well-being measures to their national agendas (Cohen, 2011; Gertner, 2010; Stiglitz, 2009). Such measures may help guide nations toward policies that decrease stress and foster human flourishing.

306

CLOSE-UP

Want to Be Happier?

Your happiness, like your cholesterol level, is genetically influenced. Yet as cholesterol is also influenced by diet and exercise, so happiness is to some extent under your personal control (Nes, 2010; Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009). Here are some research-based suggestions for building your personal strengths to increase your satisfaction with life.

Realize that enduring happiness doesn’t come from financial success. We adapt to change by adjusting our expectations. Neither wealth, nor any other circumstance we long for, will guarantee happiness.

Take control of your time. Happy people feel in control of their lives. To master your use of time, set goals and divide them into daily aims. This may be frustrating at first because we all tend to overestimate how much we will accomplish in any given day. The good news is that we generally underestimate how much we can accomplish in a year, given just a little progress every day.

Act happy. As you saw earlier in Chapter 9, people who have been manipulated into a smiling expression felt better. So put on a happy face. Talk as if you feel positive self-esteem, are optimistic, and are outgoing. We can often act our way into a happier state of mind.

Seek work and leisure that engage your skills. Happy people often are in a zone called flow—absorbed in tasks that challenge but don’t overwhelm them. Passive forms of leisure (watching TV) often provide less flow experience than exercising, socializing, or expressing your musical interests. And frequent small positive experiences make for more lasting happiness than big but rare positive events. Money also buys more happiness when spent on experiences you can look forward to, enjoy, and remember than when spent on material stuff (Carter & Gilovich, 2010).

Join the “movement” movement. Aerobic exercise can relieve mild depression and anxiety as it promotes health and energy. Sound minds reside in sound bodies. Off your duffs, couch potatoes!

Give your body the sleep it wants. Happy people live active lives yet save time for renewing sleep. Many people—high school and college students, especially—suffer from sleep debt. The result is fatigue, diminished alertness, and gloomy moods.

Give priority to close relationships. Confiding is good for soul and body. Those who care deeply about you can help you weather difficult times. Compared with unhappy people, happy people engage in less small talk and more meaningful conversations (Mehl et al., 2010). You can nurture your closest relationships by not taking your loved ones for granted. This means being as kind to them as you are to others, affirming them, playing together, and sharing together.

Focus beyond self. Reach out to those in need. Happiness increases helpfulness (those who feel good do good). But doing good also makes us feel good.

Count your blessings and record your gratitude. Keeping a gratitude journal heightens well-being (Emmons, 2007; Seligman et al., 2005). Each day, savor the good moments and positive events and record why they occurred. Express your gratitude to others.

Nurture your spiritual self. For many people, faith provides a support community, a reason to focus beyond self, and a sense of purpose and hope. That helps explain why people active in faith communities report greater-than-average happiness and often cope well with crises.

Digested from David G. Myers, The Pursuit of Happiness (Harper).

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 10.7

Which of the following factors do NOT predict self-reported happiness? Which factors are better predictors?

|

Age and gender (a. and d.) do NOT effectively predict happiness levels. Better predictors are personality traits, close relationships, “flow” in work and leisure, and religious faith (b., c., e., and f.).

307