Psychodynamic Theories

Psychodynamic theories of personality view human behavior as a lively (dynamic) interaction between the conscious and unconscious mind, and they consider our related motives and conflicts. These theories came from Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis, a historically important theory of personality that included methods for treating psychological disorders. Freud’s work was the first to focus clinical attention on our unconscious mind.

Psychodynamic theories of personality view human behavior as a lively (dynamic) interaction between the conscious and unconscious mind, and they consider our related motives and conflicts. These theories came from Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis, a historically important theory of personality that included methods for treating psychological disorders. Freud’s work was the first to focus clinical attention on our unconscious mind.

Freud’s Psychoanalytic Perspective: Exploring the Unconscious

11-1 How did Sigmund Freud’s treatment of psychological disorders lead to his view of the unconscious mind?

Freud was not psychology’s most important figure, but he is definitely the most famous. Ask 100 people on the street to name a deceased psychologist, suggested Keith Stanovich (1996, p. 1), and “Freud would be the winner hands down.” His influence lingers in books, movies, and psychological therapies. Who was Freud, what did he teach, and why do we still study his work?

Like all of us, Sigmund Freud was a product of his times. His Victorian era was a time of great discovery and scientific advancement, but it is also known today as a time of sexual repression and male dominance. Men’s and women’s roles were clearly defined, with male superiority assumed and only male sexuality generally acknowledged (discreetly).

“I know how hard it is for you to put food on your family.”

Former U.S. President George W. Bush, 2000

After graduating from the University of Vienna medical school, Freud specialized in nervous disorders. Before long, he began hearing complaints that made no medical sense. One patient had lost all feeling in one hand. Yet there is no nerve pathway that, if damaged, would numb the entire hand and nothing else. Freud wondered: What could cause such disorders? His search for the answer led in a direction that would challenge our self-understanding.

Could these strange disorders have mental rather than physical causes? Freud decided they could. Many meetings with patients led to Freud’s “discovery” of the unconscious. In Freud’s view, this deep well keeps unacceptable thoughts, wishes, feelings, and memories hidden away so thoroughly that we are no longer aware of them. But despite our best efforts, bits and pieces of these ideas seep out. Thus, according to Freud, patients might have an odd loss of feeling in their hand because they have an unconscious fear of touching their genitals. Or their unexplained blindness might be caused by unconsciously not wanting to see something that makes them anxious.

Basic to Freud’s theory was his belief that the mind is mostly hidden. Below the surface lies a large unconscious region where unacceptable passions and thoughts lurk. Freud believed we repress these unconscious feelings and ideas, blocking them from awareness, because admitting them would be too unsettling. Nevertheless, he said, these repressed feelings and ideas powerfully influence us.

For Freud, nothing was ever accidental. He saw the unconscious seeping not only into people’s troubling symptoms but also, in disguised forms, into their work, their beliefs, and their daily habits. He also glimpsed the unconscious in slips of the tongue and pen, as when a financially stressed patient, not wanting any large pills, said, “Please do not give me any bills, because I cannot swallow them.” Jokes, too, were expressions of repressed sexual and aggressive tendencies traveling in disguise. Dreams, he said, were the “royal road to the unconscious.” He thought the dreams we remember are really censored versions of our unconscious wishes.

Hoping to unlock the door to the unconscious, Freud first tried hypnosis, but with poor results. He then turned to free association, telling patients to relax and say whatever came to mind, no matter how unimportant or silly. Freud believed that free association would trace a path from the troubled present into a patient’s distant past. The chain of thought would lead back to the patient’s unconscious, the hiding place of painful past memories, often from childhood. His goal was to find these forbidden thoughts and release them.

313

Personality Structure

11-2 What was Freud’s view of personality?

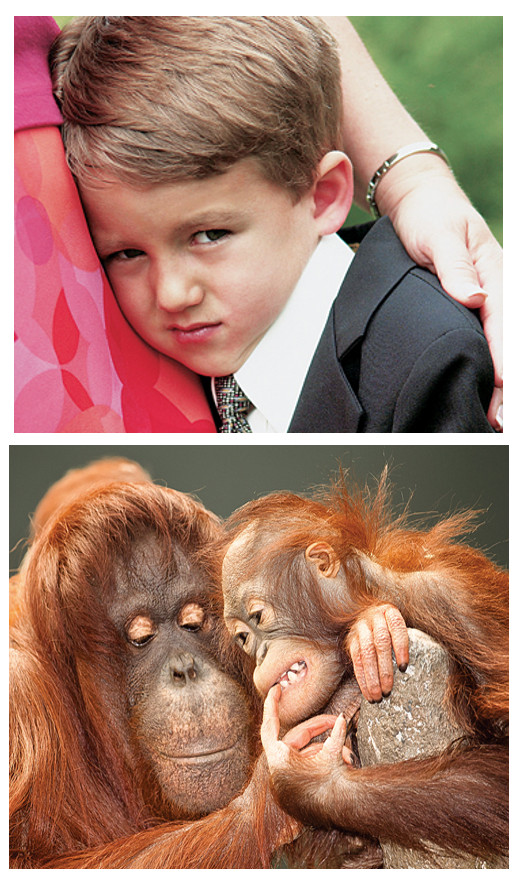

In Freud’s view, human personality arises from a conflict between impulse and restraint. People who evolved from “lower animals” are born with aggressive, pleasure-seeking urges, Freud famously said. “Man is wolf to man.” He believed that as we are socialized, we internalize social restraints against these urges. Personality is the result of our efforts to resolve basic conflict—to express these impulses in ways that bring satisfaction without guilt or punishment.

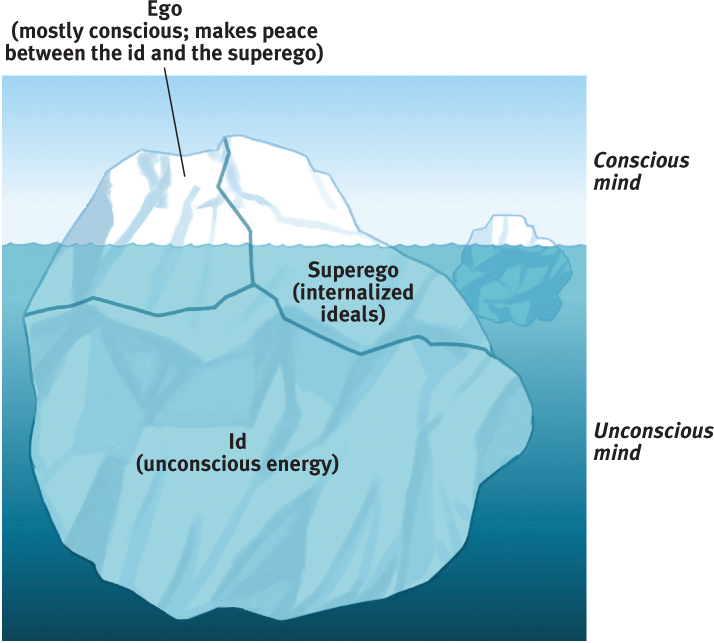

To understand the mind’s conflicts, Freud proposed three interacting systems: the id, ego, and superego. Psychologists have found it useful to view the mind’s structure as an iceberg (FIGURE 11.1) .

The id stores unconscious energy. It tries to satisfy our basic drives to survive, reproduce, and be aggressive. The id operates on the pleasure principle: It seeks immediate gratification. To see the id’s power, think of newborn infants crying out the moment they feel a need, wanting satisfaction now. Or think of people who abuse drugs, partying now rather than sacrificing today’s pleasure for future success and happiness (Keough et al., 1999).

The mind’s second part, the ego, operates on the reality principle. The ego is the conscious mind. It tries to satisfy the id’s impulses in realistic ways that will bring long-term benefits rather than pain or destruction.

As the ego develops, the young child learns to cope with the real world. Around age 4 or 5, Freud theorized, a child’s ego begins to recognize the demands of the superego, the voice of our moral compass, or conscience. The superego forces the ego to consider not only the real but the ideal. It focuses on how one ought to behave in a perfect world. It judges actions and produces positive feelings of pride or negative feelings of guilt.

As you may have guessed, the superego’s demands often oppose the id’s. It is the ego’s job to reconcile the two. As the personality’s “executive,” the ego juggles the impulsive demands of the id, the restraining demands of the superego, and the real-life demands of the external world.

314

Personality Development

11-3 What developmental stages did Freud propose?

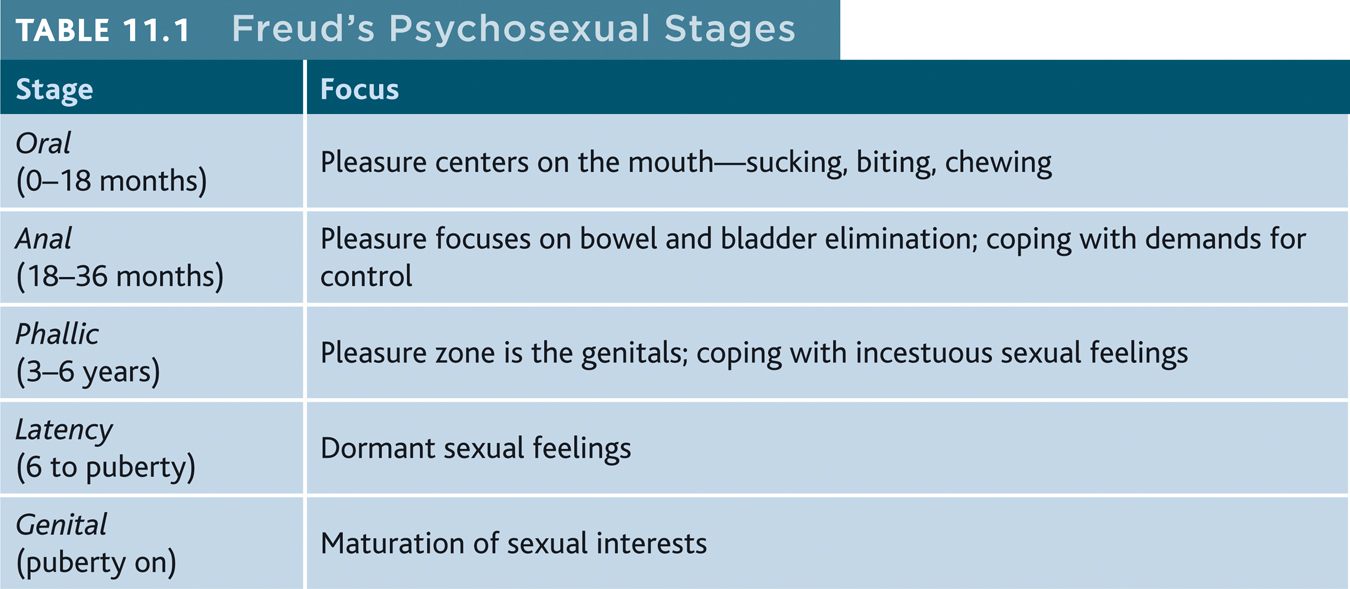

Freud believed that personality formed during life’s first few years. He was convinced that children pass through a series of psychosexual stages, from oral to genital (TABLE 11.1). In each stage, the id’s pleasure-seeking energies focus on an erogenous zone, a distinct pleasure-sensitive area of the body.

Freud believed that during the third stage, the phallic stage, boys seek genital stimulation, and they develop unconscious sexual desires for their mother. They feel jealousy and hatred for their father, who is a rival for their mother’s attention. These feelings lead to guilt and a lurking fear that their father will punish them, perhaps by castration. Freud called this cluster of feelings the Oedipus complex, after the Greek legend of Oedipus, who unknowingly killed his father and married his mother. Some psychoanalysts in Freud’s era believed that girls experienced a parallel Electra complex.

Children learn to cope with these feelings by repressing them, said Freud. They identify with the “rival” parent and try to become like him or her. It’s as though something inside the child decides, “If you can’t beat ’em, join ’em.” This identification process strengthens children’s superegos as they take on many of their parents’ values. Freud believed that identification with the same-sex parent provides what psychologists now call our gender identity—our sense of being male or female.

Other conflicts could arise at other childhood stages. But whatever the stage, unresolved conflicts can cause trouble in adulthood. The result, Freud believed, would be fixation, locking the person’s pleasure-seeking energies at the unresolved stage. A child who is either orally overindulged or orally deprived (perhaps by abrupt, early weaning) might become stalled at the oral stage, for example. As an adult, this orally fixated person might continue to seek oral gratification by smoking or excessive eating. In such ways, Freud suggested, the twig of personality is bent at an early age.

Defense Mechanisms

11-4 How did Freud think people defended themselves against anxiety?

© VStock/Alamy

Anxiety, said Freud, is the price we pay for civilization. As members of social groups, we must control our sexual and aggressive impulses, not act them out. Sometimes the ego fears losing control of this inner war between the id and superego, which results in a dark cloud of generalized anxiety. We feel unsettled, but we don’t know why.

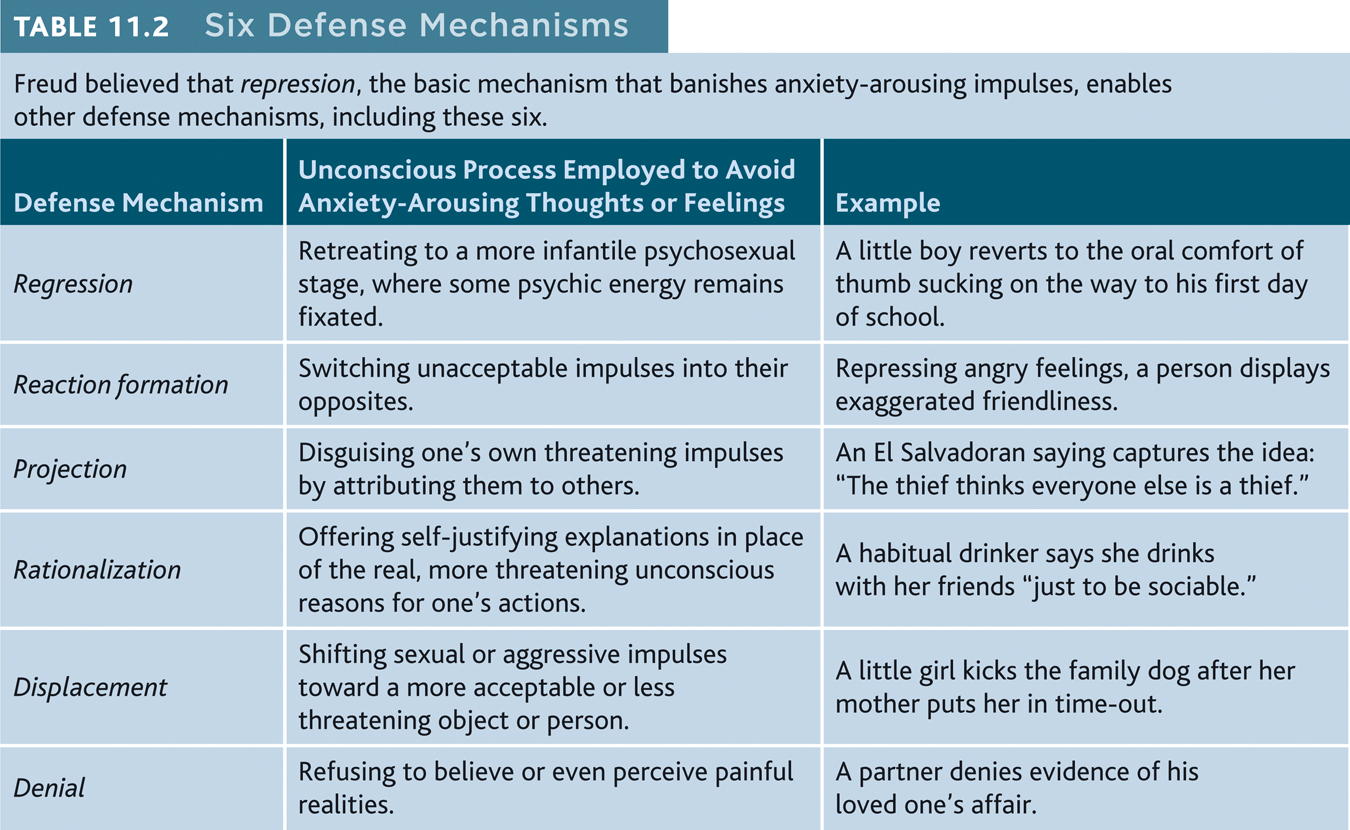

Freud proposed that the ego distorts reality in an effort to protect itself from anxiety. Defense mechanisms help achieve this goal by disguising threatening impulses and preventing them from reaching consciousness. Note that, for Freud, all defense mechanisms function indirectly and unconsciously. Just as the body unconsciously defends itself against disease, so also does the ego unconsciously defend itself against anxiety. For example, repression banishes anxiety-arousing wishes and feelings from consciousness. According to Freud, repression underlies all of the other defense mechanisms. However, because repression is often incomplete, repressed urges may appear as symbols in dreams or as slips of the tongue in casual conversation. TABLE 11.2 describes six other well-known defense mechanisms.

315

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 11.1

According to Freud’s ideas about the three-part personality structure, the __________ operates on the reality principle and tries to balance demands in a way that produces long-term pleasure rather than pain; the __________ operates on the pleasure principle and seeks immediate gratification; and the __________ represents the voice of our internalized ideals (our conscience).

ego; id; superego

Question 11.2

In the psychoanalytic view, conflicts unresolved during one of the psychosexual stages may lead to __________ at that stage.

fixation

Question 11.3

Freud believed that our defense mechanisms operate __________ (consciously/unconsciously) and defend us against __________.

unconsciously; anxiety

The Neo-Freudian and Later Psychodynamic Theorists

11-5 Which of Freud’s ideas did his followers accept or reject?

Freud’s writings caused a lot of debate. Living in a historical period when people never talked about sex, and certainly not unconscious desires for sex with one’s parent, Freud was constantly criticized. In a letter to a trusted friend, Freud wrote, “In the Middle Ages, they would have burned me. Now they are content with burning my books.” Despite the controversy, Freud attracted followers. Several young, ambitious physicians formed an inner circle around the strong-minded Freud. These neo-Freudians, such as Alfred Adler, Karen Horney [HORN-eye], and Carl Jung [Yoong], accepted Freud’s basic ideas:

- Personality has three parts: id, ego, and superego.

- The unconscious is key.

- Personality is shaped in childhood.

- We use defense mechanisms to ward off anxiety.

But the neo-Freudians differed from Freud in two important ways. First, they placed more emphasis on the role of the conscious mind. Second, they doubted that sex and aggression were all-consuming motivations. Instead, they tended to emphasize loftier motives and social interactions.

316

Some of Freud’s ideas have been incorporated into the diversity of modern perspectives that make up psychodynamic theory. Theorists and clinicians who study personality from a psychodynamic perspective assume, with Freud and with much support from today’s psychological science, that much of our mental life is unconscious. They believe we often struggle with inner conflicts among our wishes, fears, and values, and respond defensively. And they agree that childhood shapes our personality and ways of becoming attached to others. But in other ways, they differ from Freud. “Most contemporary [psychodynamic] theorists and therapists are not wedded to the idea that sex is the basis of personality,” noted psychologist Drew Westen (1996). They “do not talk about ids and egos, and do not go around classifying their patients as oral, anal, or phallic characters.”

Assessing Unconscious Processes

11-6 What are projective tests, how are they used, and how are they criticized?

Personality tests reflect the basic ideas of particular personality theories. So, what might be the tool of choice for someone working in the Freudian tradition?

To find a way into the unconscious mind, you would need a sort of “psychological X-ray.” The test would have to see through the top layer of social politeness, revealing hidden conflicts and impulses. Projective tests aim to provide this view by asking test-takers to describe an unclear image or tell a story about it. The image itself has no real meaning, but what the test-takers say about it offers a glimpse into their unconscious. (Recall that in Freudian theory, projection is a defense mechanism that disguises threatening impulses by “seeing” them in other people.)

“We don’t see things as they are; we see things as we are.”

The Talmud

The most famous projective test, the Rorschach inkblot test, was introduced in 1921. Swiss psychiatrist Hermann Rorschach [ROAR-shock] based it on a game he and his friends played as children. They would drip ink on paper, fold it, and then say what they saw in the resulting blot (Sdorow, 2005). The assumption is that what you see in a series of 10 inkblots reflects your inner feelings and conflicts. Do you see predatory animals or weapons in FIGURE 11.2 ? Perhaps you have aggressive tendencies.

Is this a reasonable assumption? Let’s see how well the Rorschach test measures up to the two primary criteria of a good test (Chapter 8):

- Reliability (consistency of results): Raters trained in different Rorschach scoring systems show little agreement (Sechrest et al., 1998).

- Validity (predicting what it’s supposed to): The Rorschach test is not very successful at predicting behavior or at discriminating between groups (for example, identifying who is suicidal and who is not). Inkblot results diagnose many normal adults as disordered (Wood et al., 2003, 2006).

317

Thus, the Rorschach test has neither much reliability nor great validity. In fact, the Rorschach test appears to have “the dubious distinction of being simultaneously the most cherished and most reviled of all psychological assessment instruments” (Hunsley & Bailey, 1999, p. 266, as quoted in Lilienfeld et al., 2000). A research-based, computer-aided coding and interpretation tool aims to improve agreement among raters and enhance the test’s validity (Erdberg, 1990; Exner, 2003). But Freud himself might have been uncomfortable with a tool that tried to diagnose patients based on tests. He probably would have been more interested in the therapist-patient interactions that take place during the test.

Evaluating Freud’s Psychoanalytic Perspective and Modern Views of the Unconscious

11-7 How do today’s psychologists view Freud’s psychoanalysis?

“Many aspects of Freudian theory are indeed out of date, and they should be: Freud died in 1939, and he has been slow to undertake further revisions,” observed one researcher (Westen, 1998). In Freud’s time, there were no neurotransmitter or DNA studies. More than eight decades of scientific breakthroughs in human development, thinking, and emotion were yet to come. Criticizing Freud’s theory by comparing it with current concepts is therefore, some say, like comparing Henry Ford’s Model T with today’s hybrid cars. (How tempting it always is to judge people in the past from our perspective in the present.)

But Freud’s admirers and critics agree that recent research contradicts many of his specific ideas. Developmental psychologists now see our development as lifelong, not fixed in childhood. They doubt that infant brain networks are mature enough to process emotional trauma in the ways Freud assumed. Some think Freud overestimated parental influence and underestimated peer influence (and abuse). They also doubt that conscience and gender identity form as the child resolves the Oedipus complex at age 5 or 6. Our gender identity develops much earlier, and we become masculine or feminine even without a same-sex parent present. And they note that Freud’s ideas about childhood sexuality have a shaky basis, in part because Freud didn’t believe his female patients’ stories of childhood sexual abuse. He apparently thought such stories reflected childhood sexual wishes and conflicts (Esterson, 2001; Powell & Boer, 1994).

Freud believed that dreams were the royal road to the unconscious, but they aren’t. Modern dream researchers disagree with Freud’s idea that dreams disguise unfulfilled wishes lurking in our unconscious (Chapter 2). And slips of the tongue can be explained as competition between similar word choices in our memory network. Someone who says, “I don’t want to do that—it’s a lot of brothel” may simply be blending bother and trouble (Foss & Hakes, 1978).

Psychology’s strength comes from its use of the same scientific method that biologists, chemists, and physicists use to test their theories. Psychologists must ask the same question about Freud’s theory that they ask about other theories. Remember that a good theory organizes observations and predicts behaviors or events (Chapter 1). How does Freudian theory stand up to the scientific tests?

Freud’s theory rests on few objective observations, and it has produced few hypotheses to verify or reject. (For Freud, his own interpretations of patients’ free associations, dreams, and slips of the tongue were evidence enough.) Moreover, say the critics, Freud’s theory offers after-the-fact explanations of behaviors and traits, but it fails to predict them. There is also no way to disprove this theory. If you feel angry when your mom dies, you illustrate his theory because “your unresolved childhood dependency needs are threatened.” If you do not feel angry, you again illustrate his theory because “you are repressing your anger.” That, say critics “is like betting on a horse after the race has been run” (Hall & Lindzey, 1978, p. 68).

Freud’s supporters object. To criticize Freudian theory for not making testable predictions is, they say, like criticizing baseball for not being an aerobic exercise, something it was never intended to be. Freud never claimed that psychoanalysis was predictive science. He merely claimed that, looking back, psychoanalysts could find meaning in their clients’ mental state (Rieff, 1979).

318

Freud’s supporters also note that some of his ideas are enduring. It was Freud who drew our attention to the unconscious and the irrational, when such ideas were not popular. Today many researchers study our irrationality (Ariely, 2010). Psychologist Daniel Kahneman won the 2002 Nobel Prize in Economics with his studies of our faulty decision making. Freud also drew our attention to the importance of human sexuality. He made us aware of the tension between our biological impulses and our social well-being. He challenged our self-righteousness, pointed out our self-protective defenses, and reminded us of our potential for evil.

Modern Research Challenges the Idea of Repression

Psychoanalytic theory hinges on the assumption that our mind represses offending wishes. Repression supposedly banishes emotions into the unconscious until they resurface, like long-lost books in a dusty attic. Today’s memory researchers find that we do sometimes spare our egos by ignoring threatening information (Green et al., 2008). Yet they also find that repression, if it ever occurs, is a rare mental response to terrible trauma. “Repression folklore is…partly refuted, partly untested, and partly untestable,” said Elizabeth Loftus (1995). Even those who have witnessed a parent’s murder or survived Nazi death camps retain their unrepressed memories of the horror (Helmreich, 1992, 1994; Malmquist, 1986; Pennebaker, 1990). This led one prominent personality researcher to conclude, “Dozens of formal studies have yielded not a single convincing case of repression in the entire literature on trauma” (Kihlstrom, 2006).

Some researchers believe that extreme, prolonged stress, such as the stress some severely abused children experience, might disrupt memory by damaging the hippocampus (Schacter, 1996). But the far more common reality is that high stress and associated stress hormones enhance memory. Indeed, rape, torture, and other traumatic events haunt survivors, who experience unwanted flashbacks. They are seared onto the soul. “You see the babies,” said Holocaust survivor Sally H. (1979). “You see the screaming mothers. You see hanging people. You sit and you see that face there. It’s something you don’t forget.”

The Modern Unconscious Mind

11-8 How has modern research developed our understanding of the unconscious?

Freud was right that we do indeed have limited access to all that goes on in our minds (Erdelyi, 1985, 1988, 2006; Kihlstrom, 1990). Our two-track mind has a vast out-of-sight realm. Some researchers even argue that “most of a person’s everyday life is determined by unconscious thought processes” (Bargh & Chartrand, 1999). But the unconscious mind studied by cognitive researchers today is not the place Freud thought it was for storing our censored anxiety-producing thoughts and seething passions. Rather, it is a part of our two-track mind, where cooler information processing occurs without our awareness, such as

- the right-hemisphere brain activity that enables the split-brain patient’s left hand to carry out an instruction the patient cannot verbalize. (Chapter 2).

- the parallel processing of different aspects of vision and thinking, and the schemas that automatically control our perceptions and interpretations (Chapter 5).

- the implicit memories that operate without our conscious recall, even among those with amnesia (Chapter 7).

- the emotions we experience instantly, before conscious analysis (Chapter 9).

- the self-concept and stereotypes that automatically and unconsciously influence how we process information about ourselves and others (Chapter 12).

More than we realize, we fly on autopilot. Our mind wanders, activating the brain’s “default network” (Mason et al., 2007). Unconscious processing occurs constantly. Like an enormous ocean, the unconscious mind is huge.

There is also research support for two of Freud’s defense mechanisms. For example, one study demonstrated reaction formation (trading unacceptable impulses for their opposite). Men who reported strong anti-gay attitudes experienced greater physiological arousal when watching videos of homosexual men having sex (as measured with an instrument that measures bloodflow to the penis) even though they said the films did not make them sexually aroused (Adams et al., 1996). Likewise, preliminary evidence suggests that people who unconsciously identify as homosexual—but who consciously identify as straight—report more negative attitudes toward gays and less support for pro-gay policies (Weinstein et al., 2012).

Freud’s projection (attributing our own threatening impulses to others) has been confirmed. People do tend to see their traits, attitudes, and goals in others (Baumeister et al., 1998; Maner et al., 2005). Today’s researchers call this the false consensus effect—the tendency to overestimate the extent to which others share our beliefs and behaviors. People who binge-drink or break speed limits tend to think many others do the same. However, defense mechanisms don’t work exactly as Freud supposed. They seem motivated less by the seething impulses he imagined than by our need to protect our self-image.

319

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 11.4

What are three values that Freud’s work in psychoanalytic theory has contributed? What are three ways in which Freud’s work has been criticized?

Freud first drew attention to (1) the importance of childhood experiences, (2) the existence of the unconscious mind, and (3) our self-protective defense mechanisms. Freud’s work has been criticized as (1) not scientifically testable—drawing on after-the-fact explanations, (2) focusing too much on sexual conflicts in childhood, and (3) based upon the idea of repression, which has not been supported by modern research.

Question 11.5

Which elements of traditional psychoanalysis do modern-day psychodynamic theorists and therapists retain, and which elements have they mostly left behind?

Today’s psychodynamic theories still tend to focus on childhood experiences and attachments, unresolved conflicts, and unconscious influences. However, they are not likely to focus on fixation at any psychosexual stage, or the idea that sexual issues influence our personality.