Exploring the Self

11-18 Why has psychology generated so much research on the self? How important is self-esteem to psychology and to our well-being?

Barry Manilow: Trinity Mirror/Mirrorpix/Alamy

We can think of our self-image as our internal view of our personality. Underlying this idea is the notion that the self is the center of personality—the organizer of our thoughts, feelings, and actions.

We can think of our self-image as our internal view of our personality. Underlying this idea is the notion that the self is the center of personality—the organizer of our thoughts, feelings, and actions.

Consider the concept of possible selves (Cross & Markus, 1991; Markus & Nurius, 1986). Your possible selves include your visions of the self you dream of becoming—the rich self, the successful self, the loved and admired self. Your possible selves also include the self you fear becoming—the unemployed self, the academically failed self, the lonely and unpopular self. Possible selves motivate us to lay out specific goals that direct our energy effectively and efficiently. High school students enrolled in a gifted program for math and science were more likely to become scientists if they had a clear vision of themselves as successful scientists (Buday et al., 2012).

Carried too far, our self-focus can lead us to fret that others are noticing and evaluating us. Researchers demonstrated this spotlight effect by having some students wear Barry Manilow T-shirts and enter a room filled with other students (Gilovich, 1996). Feeling self-conscious, the T-shirt wearers guessed that nearly half of the other students would notice the shirt as they walked in. How many did notice? Only half as many as they feared—fewer than one in four. We stand out less than we imagine, even with dorky clothes or bad hair, and even after a blunder like setting off a library alarm (Gilovich & Savitsky, 1999; Savitsky et al., 2001).

To turn down the brightness of the spotlight, we can use two strategies. The first is simply knowing about the spotlight effect. Public speakers who understand that their natural nervousness is not obvious to the audience perform better (Savitsky & Gilovich, 2003). The second is to take the perspective of an audience member. When we imagine how much an audience member empathizes with our situation, we tend to expect we will not be judged as harshly (Epley et al., 2002).

329

The Benefits of Self-Esteem

If we like our self-image, we probably have high self-esteem. This feeling of high self-worth will translate into more restful nights and less pressure to conform. We’ll be more persistent at difficult tasks. We’ll be less shy, anxious, and lonely, and, in the future, we’ll be just plain happier (Greenberg, 2008; Orth et al., 2008, 2009; Swann et al., 2007). Self-esteem tends to increase during adolescence and then stay fairly consistent over time (Erol & Orth, 2011).

Do people put themselves before others? “Who in the world am I? Ah, that’s the great puzzle!”

Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland (as quoted in Schlegel et al., 2011)

Self-esteem is a household word. College students even report wanting high self-esteem more than food or sex (Bushman et al., 2011). But most research challenges the idea that high self-esteem is really “the armor that protects kids” from life’s problems (Baumeister, 2006; Dawes, 1994; Leary, 1999; Seligman, 1994, 2002). Problems and failures lower self-esteem. So, maybe self-esteem simply reflects reality. Maybe it’s a side effect of meeting challenges and getting through difficulties. Maybe kids with high self-esteem do better in school because doing better in school raises their self-esteem. Maybe self-esteem is a gauge that reports the state of our relationships with others. If so, isn’t pushing the gauge artificially higher (with empty compliments) much like forcing a car’s low-fuel gauge to display “full”?

If feeling good follows doing well, then giving praise in the absence of good performance may actually harm people. After receiving weekly self-esteem-boosting messages, struggling students earned lower than expected grades (Forsyth et al., 2007). Other research showed that giving people random rewards hurt their productivity. Martin Seligman said, “We found that…when good things occurred that weren’t earned, like nickels coming out of slot machines, it did not increase people’s well-being. It produced helplessness. People gave up and became passive.”

330

There is, however, an important effect of low self-esteem. People who feel negatively about themselves also tend to behave negatively toward others (Amabile, 1983; Baumgardner et al., 1989; Pelham, 1993). Deflating a person’s self-esteem produces similar effects. Researchers have temporarily lowered people’s self-esteem—for example, by telling them they did poorly on a test or by insulting them. These participants were then more likely to insult others or to express racial prejudice (vanDellen et al., 2011; Van Dijk et al., 2011; Ybarra, 1999). But inflated self-esteem can also cause problems. When studying insult-triggered aggression, researchers found that “conceited, self-important individuals turn nasty toward those who puncture their bubbles of self-love” (Baumeister, 2001; Bushman et al., 2009). Narcissistic people forgive others less, take a game-playing approach to their romantic relationships, and make poor leaders (Campbell et al., 2002; Exline et al., 2004; Nevicka et al., 2011).

Self-Serving Bias

11-19 What evidence reveals self-serving bias, and how do defensive and secure self-esteem differ?

Imagine dashing to class, hoping not to miss the first few minutes. You arrive five minutes late, huffing and puffing. As you sink into your seat, what thoughts go through your mind? Do you go through a negative door, with thoughts such as, “I hate myself” and “I’m worthless”? Or do you go through a positive door, saying to yourself, “At least I made it to class” and “I really tried to get here on time”?

Personality psychologists have found that most people choose the second door, which leads to positive self-thoughts. We have a good reputation with ourselves. We show a self-serving bias—a readiness to perceive ourselves favorably (Myers, 2010; Von Hippel & Trivers, 2011). Consider these two findings:

People accept more responsibility for good deeds than for bad, and for successes than for failures . When athletes succeed, they credit their own talent. When they fail, they blame poor weather, bad luck, lousy officials, or the other team’s amazing performance. Most students who received poor grades on a test blame the test (or the professor), not themselves. On insurance forms, drivers have explained accidents in such words as “An invisible car came out of nowhere, struck my car, and vanished.” “As I reached an intersection, a hedge sprang up, obscuring my vision, and I did not see the other car.” “A pedestrian hit me and went under my car.” The question “What have I done to deserve this?” is one we usually ask of our troubles, not our successes.

“If you are like most people, then like most people, you don’t know you’re like most people. Science has given us a lot of facts about the average person, and one of the most reliable of these facts is the average person doesn’t see herself as average.”

Daniel Gilbert, Stumbling on Happiness, 2006

Most people see themselves as better than average . Compared with most other people, how nice are you? How easy to get along with? How appealing are you as a friend or romantic partner? Where would you rank yourself from 0 to 100th percentile? Most people put themselves well above the 50th percentile. This better-than-average effect applies for nearly any common, socially desirable behavior. Most business executives say they are more ethical than the average executive. At least 90 percent of business managers and college professors rate their performance as superior to that of their average peer. This tendency is less striking in Asia, where people value modesty (Heine & Hamamura, 2007). Yet self-serving biases have been observed worldwide: among Dutch, Australian, and Chinese students; Japanese drivers; Indian Hindus; and French people of most walks of life. In every one of 53 countries surveyed, people expressed self-esteem above the midpoint of the most widely used scale (Schmitt & Allik, 2005).

331

Most people even see themselves as more immune than others to self-serving bias (Pronin, 2007). That’s right, people believe they are above average at not believing they are above average. (Isn’t psychology fun?) We also are quicker to believe flattering descriptions of ourselves than unflattering ones, and we are impressed with psychological tests that make us look good.

Self-serving bias often underlies conflicts, such as blaming a spouse for marriage problems or an assistant for work problems. All of us tend to see our own group as superior (whether it’s our school, our ethnic group, or our country). Ethnic pride fueled Nazi horrors and Rwandan genocide. No wonder religion and literature so often warn against the perils of self-love and pride.

If the self-serving bias is so common, why do so many people put themselves down? For four reasons:

- Some negative thoughts—“How could I have been so stupid!”—protect us from repeating mistakes.

- Self put-downs are sometimes meant to prompt positive feedback. Saying “No one likes me” may at least get you “But not everyone has met you!”

- Put-downs can help prepare us for possible failure. The coach who talks about the superior strength of the upcoming opponent makes a loss understandable, a victory noteworthy.

- We often put down our old selves, not our current selves (Wilson & Ross, 2001). Chumps yesterday, but champs today: “At 18, I was a jerk; today I’m more sensitive.”

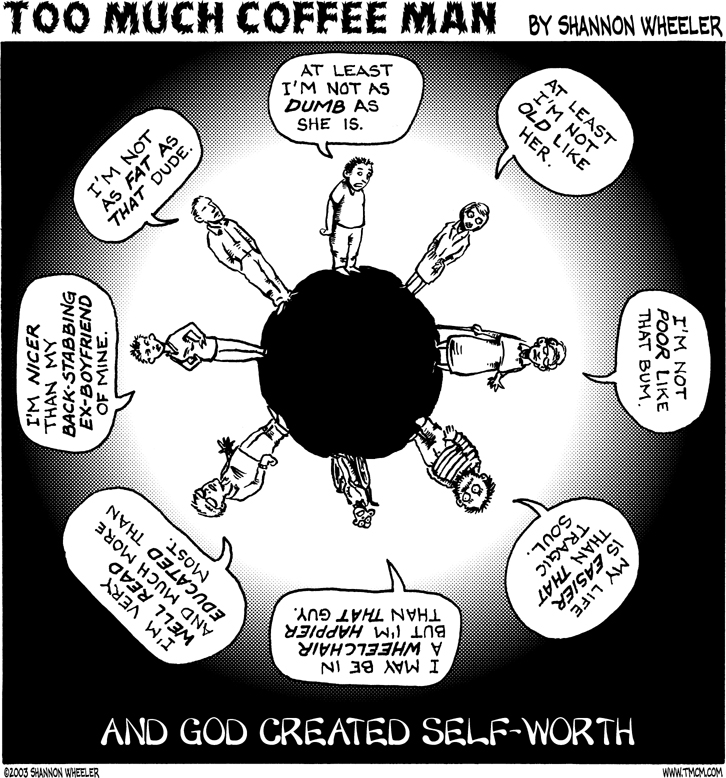

Despite our self-serving bias, all of us some of the time, and some of us much of the time, do feel inferior. As we saw in Chapter 10, this often happens when we compare ourselves with those who are a step or two higher on the ladder of status, looks, income, or ability. For example, Olympians who win silver medals, barely missing gold, show greater sadness on the award podium compared with the bronze medal winners (Medvec et al., 1995). The more deeply and frequently we have such feelings, the more unhappy, even depressed, we are. Positive self-esteem predicts happiness and persistence after failure (Baumeister et al., 2003). So maybe it helps that, for most people, thinking has a naturally positive bias.

Researchers have shown the value of separating self-esteem into two categories—defensive and secure (Kernis, 2003; Lambird & Mann, 2006; Ryan & Deci, 2004).

- Defensive self-esteem is fragile. Its goal is to sustain itself, which makes failures and criticism feel threatening. Defensive self-esteem feeds anger and disordered responses to threats (Crocker & Park, 2004). It correlates with aggressive and antisocial behavior (Donnellan et al., 2005).

- Secure self-esteem is sturdy. It relies less on other people’s evaluations. If we feel accepted for who we are, and not for our looks, wealth, or fame, we are free of pressures to succeed. We can focus beyond ourselves, losing ourselves in relationships and purposes larger than self. Secure self-esteem thus leads to greater quality of life. Such findings are in line with Maslow’s and Rogers’ ideas about the benefits of a healthy self-image.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 11.12

The tendency to accept responsibility for success and blame circumstances or bad luck for failures is called __________ - __________ __________. The tendency to overestimate others’ attention to and evaluation of our appearance, performance, and blunders is called the __________ __________.

self-serving bias; spotlight effect

Question 11.13

__________ (Secure/Defensive) self-esteem correlates with aggressive and antisocial behavior. (Secure/Defensive) self-esteem is a healthier self-image that allows us to focus beyond ourselves and enjoy a higher quality of life.

Defensive; Secure

Culture and the Self

11-20 How do individualist and collectivist cultures influence people?

The meaning of self varies from culture to culture. How much of your identity is defined by your social connections? Your answer may depend on your culture, and whether it gives greater priority to the independent self or to the interdependent self.

If you are an individualist, you have an independent sense of “me,” and an awareness of your unique personal convictions and values. Individualists give higher priority to personal goals. They define their identity mostly in terms of personal traits. They strive for personal control and individual achievement.

Although within cultures we vary, different cultures tend to emphasize either individualism or collectivism. The United States is mostly an individualist culture. Founded by settlers who wanted to differentiate themselves from others, Americans still cherish the “pioneer” spirit (Kitayama et al., 2010). Some 85 percent of Americans say it is possible “to pretty much be who you want to be” (Sampson, 2000). Being more self-contained, individualists also move in and out of social groups more easily. They change relationships, towns, and jobs with ease.

332

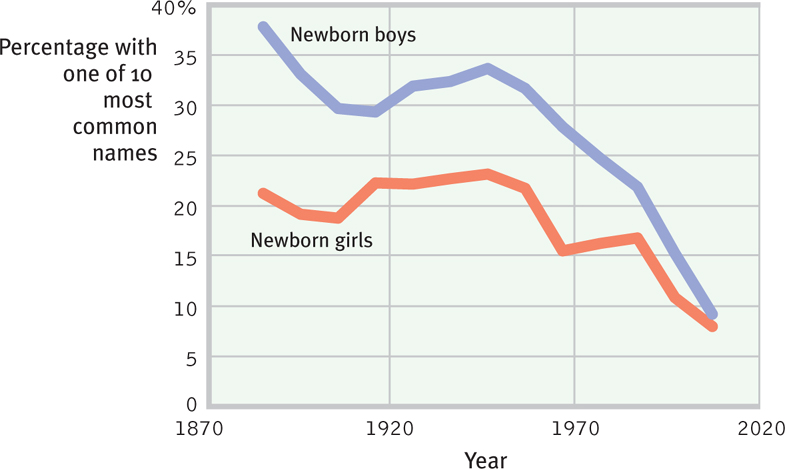

Over the past several decades, U.S. individualism has only increased. American high school and college students in 2012 reported greater interest in obtaining benefits for themselves and lower concern for others than ever before (Twenge et al., 2012). The need for uniqueness has even crept into the names people choose for their children (FIGURE 11.6). Even within the United States, parents from more recently settled states (for example, Utah and Arizona) give their children more distinctive names compared with parents who live in more established states (for example, New York and Massachusetts) (Varnum & Kitayama, 2011).

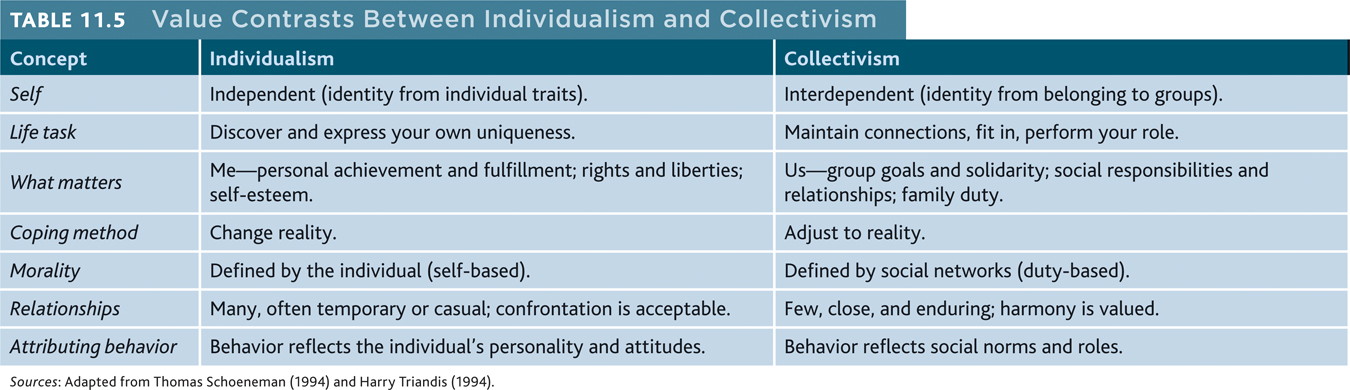

People in competitive, individualist cultures have more personal freedom (TABLE 11.5). They take more pride in personal achievements, are less geographically bound to their families, and enjoy more privacy. But these benefits come at the cost of more loneliness, divorce, homicide, and stress-related disease (Popenoe, 1993; Triandis et al., 1988). People in individualist cultures also demand more romance and personal fulfillment in marriage, which puts relationships under more pressure (Dion & Dion, 1993). In one survey, “keeping romance alive” was rated as important to a good marriage by 78 percent of U.S. women but only 29 percent of Japanese women (American Enterprise, 1992).

If you are a collectivist, your identity may be closely tied to family, groups, and loyal friends. These connections define who you are. Group identifications provide a sense of belonging and a set of values in collectivist cultures. In Korea, for example, people place less value on expressing a consistent, unique self-concept, and more on tradition and shared practices (Choi & Choi, 2002).

333

Collectivists are like athletes who take more pleasure in their team’s victory than in their own performance. They find satisfaction in advancing their groups’ interests, even at the expense of personal needs. Preserving group spirit and avoiding social embarrassment are important goals. Collectivists therefore avoid direct confrontation, blunt honesty, and uncomfortable topics. They value humility, not self-importance (Bond et al., 2012). Instead of dominating conversations, collectivists hold back and display shyness when meeting strangers (Cheek & Melchior, 1990). Elders receive great respect. In some collectivist cultures, it is even against the law to disrespect elders. For example, the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Protection of the Rights and Interests of the Elderly states that parents aged 60 or above can sue their sons and daughters if they fail to follow through on their legal obligation of “providing for the elderly, taking care of them and comforting them, and cater[ing] to their special needs” (Chapter 11, Article 11).

Individualist proverb: “The squeaky wheel gets the grease.”

Collectivist proverb: “The quacking duck gets shot.”

Collectivist cultures place little expectation or value on having a consistent, coherent self-concept because one’s identity depends on others in the social context (Heine & Buchtel, 2009). Even if East Asians report inconsistency in their self-concept across different relationship partners, they still feel authentic (English & Chen, 2011). In contrast, European-Americans do not feel authentic if their self-concept changes across relationship partners.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 11.14

How do individualist and collectivist cultures differ?

Individualists give priority to personal goals over group goals and tend to define their identity in terms of their own personal attributes. Collectivists give priority to group goals over individual goals and tend to define their identity in terms of group identifications.

* * *

Enduring, inner influences on behavior are the focus of personality psychology, as we've now seen. Temporary, outside influences on behavior are the focus of social psychology—the area we turn to next. In reality, behavior always depends on the interaction of persons with situations.