Social Thinking

When we try to explain people’s actions, our search for answers often leaves us with two choices. We can attribute behavior to a person’s stable, enduring traits. Or we can attribute behavior to the situation (Heider, 1958). Our explanations, or attributions, affect our feelings and actions.

When we try to explain people’s actions, our search for answers often leaves us with two choices. We can attribute behavior to a person’s stable, enduring traits. Or we can attribute behavior to the situation (Heider, 1958). Our explanations, or attributions, affect our feelings and actions.

The Fundamental Attribution Error

12-2 How does the fundamental attribution error describe how we tend to explain others’ behavior compared with our own?

In class, we notice that Juliette seldom talks. Over coffee, Jack talks nonstop. That must be the sort of people they are, we decide. Juliette must be shy and Jack outgoing. Are they? Perhaps. People do have enduring personality traits. But often our explanations are wrong. We fall prey to the fundamental attribution error : We give too much weight to the influence of personality and too little to the influence of situations. In class, Jack may be as quiet as Juliette. Catch Juliette at a party and you may hardly recognize your quiet classmate.

Researchers demonstrated this tendency in an experiment with college students (Napolitan & Goethals, 1979). They had students talk, one at a time, with a young woman who acted either cold and critical or warm and friendly. Before the talks, the researchers told half the students that the woman’s behavior would be normal and natural. They told the other half the truth—that they had instructed her to act friendly (or unfriendly).

Did hearing the truth affect students’ impressions of the woman? Not at all! If the woman acted friendly, both groups decided she really was a warm person. If she acted unfriendly, both decided she really was a cold person. In other words, they attributed her behavior to her personal traits, even when they were told that her behavior was part of the experimental situation.

The fundamental attribution error appears more often in some cultures than in others. Individualist Westerners more often attribute behavior to people’s personal traits. People in East Asian cultures are more sensitive to the power of situations (Masuda & Kitayama, 2004). This difference appeared in experiments in which people were asked to view scenes, such as a big fish swimming. Americans focused more on the individual fish; Japanese people focused on the whole scene (Chua et al., 2005; Nisbett, 2003).

To see how easily we make the fundamental attribution error, answer this question: Is your psychology instructor shy or outgoing?

If you’re tempted to answer “outgoing,” remember that you know your instructor from one situation—the classroom, which demands outgoing behavior. Your instructor (who observes his or her own behavior not only in the classroom, but also with family, friends, and colleagues) might say, “Me, outgoing? It all depends on the situation. In class or with good friends, yes, I’m outgoing. But at professional meetings I’m really rather shy.” Outside the classroom, professors seem less professorial, students less studious.

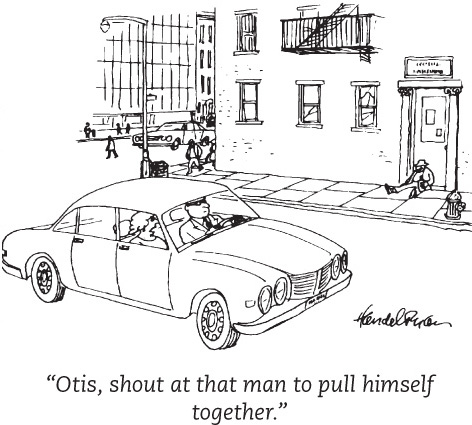

When we explain our own behavior, we are sensitive to how behavior changes with the situation (Idson & Mischel, 2001). We also are sensitive to the power of the situation when we explain the behavior of people we have seen in many different contexts. So, when are we most likely to commit the fundamental attribution error? The odds are highest when a stranger acts badly. Having never seen this person in other situations, we assume he must be a bad person. But outside the stadium, that red-faced man screaming at the referee may be a great neighbor and a good father.

As we act, our eyes look outward; we see others’ faces, not our own. If we could take an observer’s point of view, would we become more aware of our own personal style? To test this idea, researchers have filmed two people interacting with a camera behind each person. Then they showed each person a replay of their interaction—filmed from the other person’s perspective. It worked. Seeing their behavior from the other person’s perspective, participants better appreciated the power of the situation (Lassiter & Irvine, 1986; Storms, 1973).

339

Reflecting on our past selves of 5 or 10 years ago also switches our perspective. Our present self adopts the observer’s perspective and attributes our past behavior mostly to our traits (Pronin & Ross, 2006). In another 5 or 10 years, your current self may seem like another person.

The way we explain others’ actions, attributing them to the person or the situation, can have important real-life effects (Fincham & Bradbury, 1993; Fletcher et al., 1990). A person must decide whether another’s warm greeting reflects friendliness or a romantic interest. A jury must decide whether a shooting was an attack or an act of self-defense. A voter must judge whether a candidate’s promises are sincere or soon to be forgotten. A partner must decide whether a loved one’s acid-tongued remark reflects a bad day or a serious rejection.

Finally, consider the social effects of attribution. How should we explain poverty or unemployment? In Britain, India, Australia, and the United States, political conservatives have tended to place the blame on the personal traits of the poor and unemployed (Furnham, 1982; Pandey et al., 1982; Wagstaff, 1982; Zucker & Weiner, 1993). “People generally get what they deserve. Those who don’t work are often freeloaders. Anybody who tries hard can still get ahead.” In experiments, after reflecting on the power of choice—either by recalling their own choices or taking note of another’s choices—people are less bothered by inequality. They are more likely to think people get what they deserve (Savani & Rattan, 2012). Those not asked to consider the power of choice are more likely to blame past and present situations. So are political liberals.

The point to remember: Our attributions—to someone’s personal traits or to the situation—have real consequences.

Attitudes and Actions

12-3 What is an attitude, and how do attitudes and actions affect each other?

Attitudes are feelings, often based on our beliefs, that can influence how we respond to particular objects, people, and events. If we believe someone is mean, we may feel dislike for the person and act unfriendly. That helps explain a noteworthy finding. If people in a country intensely dislike the leaders of another country, their country is more likely to produce terrorist acts against that country (Krueger & Malecková, 2009). Hateful attitudes breed violent behavior.

Attitudes Affect Actions

Attitudes affect our behavior, but other factors, including the situation, also influence behavior. For example, in roll-call votes, situational pressures can control behavior. Forced to state publicly their support or opposition, politicians may vote as their supporters demand, despite privately disagreeing with those demands (Nagourney, 2002).

When are attitudes most likely to affect behavior? Under these conditions (Glasman & Albarracin, 2006):

- External influences are minimal.

- The attitude is stable.

- The attitude is specific to the behavior.

- The attitude is easily recalled.

One experiment used vivid, easily recalled information to persuade people that sustained tanning put them at risk for future skin cancer. One month later, 72 percent of the participants, and only 16 percent of those in a waitlist control group, had lighter skin (McClendon & Prentice-Dunn, 2001). Changed attitudes can change behavior.

Actions Affect Attitudes

People also come to believe in what they have stood up for. Many streams of evidence confirm that attitudes follow behavior (FIGURE 12.1) .

FOOT-IN-THE-DOOR PHENOMENON How would you react if someone got you to act against your beliefs? Would you change your beliefs? Many people do. During the Korean war, many U.S. prisoners were held in Chinese communist camps. Without using brutality, the Chinese captors gained prisoners’ cooperation in various activities. Some merely did simple tasks to gain privileges. Others made radio appeals and false confessions. Still others informed on other prisoners and revealed military information. When the war ended, 21 prisoners chose to stay with the communists. More returned home “brain-washed”—convinced that communism was good for Asia.

340

How did the Chinese captors achieve these amazing results? A key ingredient was their effective use of the foot-in-the-door phenomenon. They knew that people who agree to a small request will find it easier to agree later to a larger one. The Chinese began with harmless requests, such as copying a trivial statement. Gradually, they made bigger demands (Schein, 1956). The next statement to be copied might contain a list of the flaws of capitalism. Then, to gain privileges, the prisoners took part in group discussions, wrote self-criticisms, or made public confessions. After taking this series of small steps, some of the Americans changed their beliefs to be more in line with their public acts. The point is simple. To get people to agree to something big, start small and build (Cialdini, 1993). A trivial act makes the next act easier. Give in to a temptation and you will find the next temptation harder to resist.

In dozens of experiments, researchers have coaxed people into acting against their attitudes or violating their moral standards, with the same result. Doing becomes believing. After giving in to a request to harm an innocent victim—by making nasty comments or delivering electric shocks—people begin to look down on their victim. After speaking or writing in support of a position they have doubts about, they begin to believe their own words.

Fortunately, the principle that attitudes follow behavior works as well for good deeds as for bad. After U.S. schools were desegregated and the 1964 Civil Rights Act was passed, White Americans expressed lower levels of racial prejudice. And as Americans in different regions came to act more alike—thanks to more uniform national standards against discrimination—they began to think more alike. Experiments confirm the observation: Moral action strengthens moral convictions.

ROLE-PLAYING AFFECTS ATTITUDES How many new roles have you adopted recently? Becoming a college student is a new role. Perhaps you’ve started a new job, or a new relationship, or even become engaged or married. If so, you may have realized that people expected you to behave a little differently. At first, your behaviors may have felt phony, because you were acting a role. Soldiers may at first feel they are playing war games. Newlyweds may feel they are “playing house.” Before long, however, what began as play-acting in the theater of life becomes you. (This fact is reflected in the Alcoholics Anonymous advice: “Fake it until you make it.”)

Role-playing morphed into real life in one famous study in which male college students volunteered to spend time in a mock prison (Zimbardo, 1972). Psychologist Philip Zimbardo randomly assigned some volunteers to be guards. He gave them uniforms, clubs, and whistles and instructed them to enforce certain rules. Others became prisoners, locked in barren cells and forced to wear humiliating outfits. For a day or two, the volunteers self-consciously played their roles. Then it became clear that the “play” had become real—too real. Most guards developed bad attitudes. Some set up cruel routines. One by one, the prisoners broke down, rebelled, or became passively resigned. After only six days, Zimbardo called off the study.

AP Photo

Role-playing can also train people to become torturers in the real world (Staub, 1989). Yet people differ. In Zimbardo’s prison simulation, and in other atrocity-producing situations, some people gave in to the situation and others did not (Carnahan & McFarland, 2007; Haslam & Reicher, 2007; Mastroianni & Reed, 2006; Zimbardo, 2007). Persons and situations interact.

341

COGNITIVE DISSONANCE: RELIEF FROM TENSION We have seen that actions can affect attitudes, sometimes turning prisoners into collaborators, doubters into believers, and guards into abusers. But why? One explanation is that when we become aware of a mismatch between our attitudes and actions, we experience mental discomfort, or cognitive dissonance. Indeed, the brain regions that become active when people experience cognitive conflict and negative arousal also become active when people experience cognitive dissonance (Kitayama et al., 2013). To relieve this tension, according to Leon Festinger’s cognitive dissonance theory, we often bring our attitudes into line with our actions.

Dozens of experiments have tested this attitudes-follow-behavior principle. Many have made people feel responsible for behavior that clashed with their attitudes. As a participant in one of these experiments, you might agree for a mere $2 to help a researcher by writing an essay that supports something you don’t believe in (perhaps a tuition increase). Feeling responsible for your written statements (which don’t reflect your attitudes), you would probably feel dissonance, especially if you thought an administrator would be reading your essay. How could you reduce the uncomfortable tension? One way would be to start believing your phony words. It’s as if we tell ourselves, “If I chose to do it (or say it), I must believe in it.” Thus, we may change our attitudes to help justify the act.

The attitudes-follow-behavior principle can also help us become better people. We cannot control all our feelings, but we can influence them by altering our behavior. (Recall from Chapter 9 the emotional effects of facial expressions and of body postures.) If we are down in the dumps, we can do as cognitive therapists advise: We can talk in more positive, self-accepting ways with fewer self-put-downs. If we are unloving, we can become more loving: We can do thoughtful things, express affection, give support.

The point to remember: Cruel acts shape the self. But so do acts of good will. Act as though you like someone, and you soon may. Changing our behavior can change how we think about others and how we feel about ourselves.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 12.1

Driving to school one snowy day, Marco narrowly misses a car that slides through a red light. “Slow down! What a terrible driver,” he thinks to himself. Moments later, Marco himself slips through an intersection and yelps, “Wow! These roads are awful. The city plows need to get out here.” What social psychology principle has Marco just demonstrated? Explain.

By attributing the other person’s behavior to personal traits (“what a terrible driver”) and his own to the situation (“these roads are awful”), Marco has exhibited the fundamental attribution error.

Question 12.2

How do our attitudes and our actions affect each other?

Our attitudes often influence our actions, as we behave in ways consistent with our beliefs. However, our attitudes also follow our actions; we come to believe in what we have done.

Question 12.3

When people act in a way that is not in keeping with their attitudes, and then change their attitudes to match those actions, __________ __________ theory attempts to explain why.

cognitive dissonance