Social Influence

Social psychology’s great lesson is the enormous power of social influence. We adjust our views to match the desires of those around us. We follow orders. We behave as others in our group behave. On campus, jeans are the dress code. On New York’s Wall Street, dress suits are the norm. Let’s examine the pull of these social strings. How strong are they? How do they operate? When do we break them?

Social psychology’s great lesson is the enormous power of social influence. We adjust our views to match the desires of those around us. We follow orders. We behave as others in our group behave. On campus, jeans are the dress code. On New York’s Wall Street, dress suits are the norm. Let’s examine the pull of these social strings. How strong are they? How do they operate? When do we break them?

Conformity and Obedience

12-4 What do experiments on conformity and obedience reveal about the power of social influence?

Fish swim in schools. Birds fly in flocks. And humans, too, tend to go with their group—to think what it thinks and do what it does. Behavior is catching. If one of us laughs, coughs, yawns, or stares at the sky, others in our group will soon do the same. Like the chameleon lizards that take on the color of their surroundings, we humans take on the emotional tones of those around us (Totterdell et al., 1998). We are natural mimics, unconsciously imitating others’ expressions, postures, and voice tones.

Researchers demonstrated this chameleon effect in a clever experiment (Chartrand & Bargh, 1999). They had students work in a room beside another person, who was actually the experimenter’s assistant. Sometimes the assistants rubbed their own face. Sometimes they shook their foot. Sure enough, the students tended to rub their face when with the face-rubbing person and shake their foot when with the foot-shaking person.

Automatic mimicry helps us to empathize, to feel what others feel. This helps explain why we feel happier around happy people than around depressed ones. The more we mimic, the greater our empathy, and the more people tend to like us.

342

Group Pressure and Conformity

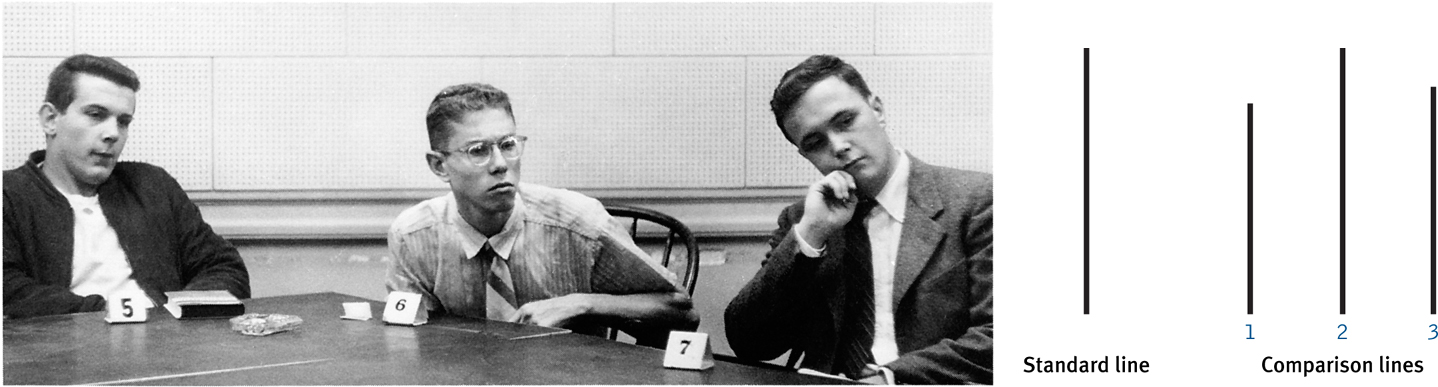

To study conformity—adjusting our behavior or thinking toward some group standard—Solomon Asch (1955) designed a simple test. As a participant in what you believe is a study of visual perception, you arrive in time to take a seat at a table with five other people. The experimenter asks the group to state, one by one, which of three comparison lines is identical to a standard line. You see clearly that the answer is Line 2, and you await your turn to say so. Your boredom begins to show when the next set of lines proves equally easy.

Now comes the third trial, and the correct answer seems just as clear-cut (FIGURE 12.2). But the first person gives what strikes you as a wrong answer: “Line 3.” When the second person and then the third and fourth give the same wrong answer, you sit up straight and squint. When the fifth person agrees with the first four, you feel your heart begin to pound. The experimenter then looks to you for your answer. Torn between the agreement voiced by the five others and the evidence of your own eyes, you feel tense and suddenly unsure of yourself. You wait a bit before answering, wondering whether you should suffer the pain of being the odd-ball. What answer do you give?

In Asch’s experiments, college students experienced this conflict. Answering questions alone, they were wrong less than 1 percent of the time. But the odds were quite different when several others—people actually working for Asch—answered incorrectly. Although most people told the truth even when others did not, Asch was disturbed by his result. More than one-third of the time, these “intelligent and well-meaning” college students were then “willing to call white black” by going along with the group.

Experiments reveal that we are more likely to conform when we

- are made to feel incompetent or insecure.

- are in a group with at least three people.

- are in a group in which everyone else agrees. (If just one other person disagrees, we will almost surely disagree.)

- admire the group’s status and attractiveness.

- have not already committed ourselves to any response.

- know that others in the group will observe our behavior.

- are from a culture that strongly encourages respect for social standards.

Why do we so often think what others think and do what they do? Why in college residence halls do students’ attitudes become more similar to those living near them (Cullum & Harton, 2007)? Why in classrooms are hand-raised answers to controversial questions more alike than answers given by anonymous electronic clicker responses (Stowell et al., 2010)? Why do we clap when others clap, eat as others eat, believe what others believe, even see what others see? Sometimes it’s to avoid rejection or to gain social approval. So we respond to social norms—a group’s rules for “proper” behavior. But groups also provide information that can benefit open-minded people. “Those who never retract their opinions love themselves more than they love truth,” observed Joseph Joubert, an eighteenth-century French essayist.

Is conformity good or bad? The answer depends on our values. When people conform to influences that support what we approve, we applaud them for being “open-minded” and “sensitive” enough to be “responsive.” When they conform to influences that support what we disapprove, we scorn their “blind, thoughtless” willingness to give in to others’ wishes.

Our values, as we saw in Chapter 11, are influenced by our culture. Western Europeans and people in most English-speaking countries tend to prize individualism. People in many Asian, African, and Latin American countries place a higher value on honoring group standards (collectivism). It’s perhaps not surprising, then, that in social influence experiments across 17 countries, conformity rates are lower in individualist cultures than in collectivist cultures (Bond & Smith, 1996). In the United States, for example, university students tend to see themselves as less conforming than others (Pronin et al., 2007). We are, in our own eyes, individuals amid a flock of sheep.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 12.4

Which of the following strengthens conformity to a group?

|

a

Obedience

Social psychologist Stanley Milgram (1963, 1974), a student of Solomon Asch and a high school classmate of Phillip Zimbardo, knew that people often give in to social pressure. But how would they respond to outright commands? To find out, he undertook experiments that have become social psychology’s most famous and most hotly debated.

“Have you ever noticed how one example—good or bad—can prompt others to follow? How one illegally parked car can give permission for others to do likewise? How one racial joke can fuel another?”

Marian Wright Edelman, The Measure of Our Success, 1994

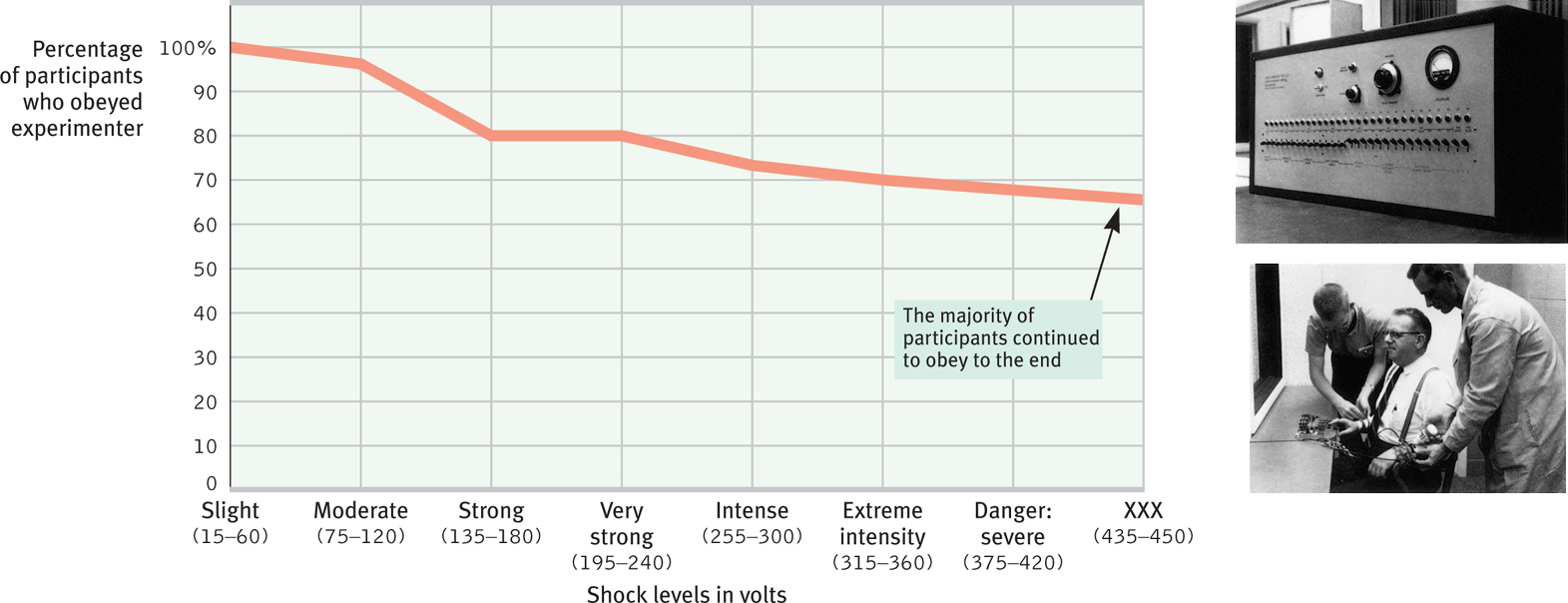

Imagine yourself as one of the nearly 1000 people who took part in Milgram’s 20 experiments. You have responded to an ad for participants in a Yale University psychology study of the effect of punishment on learning. Professor Milgram’s assistant asks you and another person to draw slips from a hat to see who will be the “teacher” and who will be the “learner.” You draw the “teacher” slip and are asked to sit down in front of a machine, which has a series of labeled switches. The “learner” is led to a nearby room and strapped into a chair. From the chair, wires run through the wall to “your” machine. You are given your task: Teach and then test the learner on a list of word pairs. If the learner gives a wrong answer, you are to flip a switch to deliver a brief electric shock. For the first wrong answer, you will flip the switch labeled “15 Volts—Slight Shock.” With each succeeding error, you will move to the next higher voltage. The researcher demonstrates by flipping the first switch. Lights flash, relay switches click on, and an electric buzzing fills the air.

344

The experiment begins, and you deliver the shocks after the first and second wrong answers. If you continue, you hear the learner grunt when you flick the third, fourth, and fifth switches. After you flip the eighth switch (“120 Volts—Moderate Shock”), the learner cries out that the shocks are painful. After the tenth switch (“150 Volts—Strong Shock”), he begins shouting. “Get me out of here! I won’t be in the experiment anymore! I refuse to go on!” You draw back, but the experimenter prods you. “Please continue—the experiment requires that you continue.” You resist, but the experimenter insists, “It is absolutely essential that you continue,” or “You have no other choice, you must go on.”

If you obey, you hear the learner shriek in agony as you continue to raise the shock level after each new error. After the 330-volt level, the learner refuses to answer and falls silent. Still, the experimenter pushes you toward the final, 450-volt switch. Ask the question, he says, and if no correct answer is given, administer the next shock level.

Would you follow an experimenter’s commands to shock someone? At what level would you refuse to obey? Milgram asked that question in a survey before he started his experiments. Most people were sure they would stop playing such a sadistic-seeming role soon after the learner first indicated pain, certainly before he shrieked in agony. Forty psychiatrists agreed with that prediction when Milgram asked them. Were the predictions accurate? Not even close. When Milgram actually conducted the experiment with men aged 20 to 50, he was amazed. More than 60 percent followed orders—right up to the last switch. Even when Milgram ran a new study, with 40 new teachers, and the learner complained of a “slight heart condition,” the results were the same. A full 65 percent of the new teachers obeyed every one of the experimenter’s commands, right up to 450 volts (FIGURE 12.3).

How can we explain these findings? Could they be a product of the 1960s culture? Would people today be less likely to obey an order to hurt someone? No. When researchers replicated Milgram’s basic experiment, 70 percent of the participants obeyed up to the 150-volt point (Burger, 2009). This is only a slight reduction from Milgram’s 80 percent at that level. And in a French reality TV show replication, 80 percent of people, egged on by a cheering audience, obeyed and tortured a screaming victim (de Moraes, 2010).

Could Milgram’s findings reflect some aspect of gender behavior found only in males? Again, the answer is No. In 10 later studies, women obeyed at rates similar to men (Blass, 1999).

Did the teachers figure out the hoax—that no real shock was being delivered and the learner was in fact an assistant only pretending to feel pain? Did they realize the experiment was really testing their willingness to obey commands to inflict punishment? No, the teachers were typically genuinely distressed. They perspired, trembled, laughed nervously, and bit their lips.

345

In later experiments, Milgram discovered some things that did influence people’s behavior. When he varied some details of the situation, the percentage of participants who fully obeyed ranged from 0 to 93 percent. Obedience was highest when

- the person giving the orders was close at hand and was perceived to be a legitimate authority figure.

- the authority figure was supported by a respected, well-known institution (Yale University).

- the victim was depersonalized or at a distance, even in another room. Similarly, many soldiers in combat either do not fire their rifles at an enemy they can see or do not aim them properly. Such refusals to kill are rare among those who kill from a distance. (Veterans who operated remotely piloted drones have suffered less posttraumatic stress than is found among on-the-ground Afghanistan and Iraq war veterans [Miller, 2012; Padgett, 1989].)

- there were no role models for defiance. (Teachers did not see any other participant disobey the experimenter.)

The power of legitimate, close-at-hand authorities is dramatically apparent in stories of those who followed orders to carry out the Holocaust atrocities. Obedience alone does not explain the Holocaust. Anti-Semitic ideology produced eager killers as well (Mastroianni, 2002). But obedience was a factor. In the summer of 1942, nearly 500 middle-aged German reserve police officers were dispatched to German-occupied Jozefow, Poland. On July 13, the group’s visibly upset commander informed his recruits, mostly family men, of their orders. They were to round up the village’s Jews, who were said to be aiding the enemy. Able-bodied men would be sent to work camps, and all the rest were to be shot on the spot.

The commander gave the recruits a chance to refuse to participate in the executions. Only about a dozen immediately refused. Within 17 hours, the remaining 485 officers killed 1500 helpless women, children, and elderly, shooting them in the back of the head as they lay face down. Hearing the victims’ pleas and seeing the gruesome results, some 20 percent of the officers did eventually disobey. They did so either by missing their victims or by wandering away and hiding until the slaughter was over (Browning, 1992). In real life, as in Milgram’s experiments, those who resisted did so early, and they were the minority.

“I was only following orders.”

Adolf Eichmann, Director of Nazi deportation of Jews to concentration camps

Another story was being played out in the French village of Le Chambon. There, French Jews were being sheltered by villagers who openly defied orders to cooperate with the “New Order.” The villagers’ ancestors had themselves been persecuted. Their pastors had been teaching them to “resist whenever our adversaries will demand of us obedience contrary to the orders of the Gospel” (Rochat, 1993). Ordered by police to give a list of sheltered Jews, the head pastor modeled defiance. “I don’t know of Jews, I only know of human beings.” These resistors had no idea how long and terrible the war would be, or how much punishment and poverty they would suffer. But early on, they made a commitment to resist. After that, they drew support from their beliefs, their role models, their interactions with one another, and their own early actions. They remained defiant to the war’s end.

Lessons From the Conformity and Obedience Studies

12-5 What do the social influence studies teach us about ourselves? How much power do we have as individuals?

How do the laboratory experiments on social influence relate to everyday life? Psychology’s experiments aim not to re-create the exact behaviors of everyday life but to explore what influences them. Solomon Asch and Stanley Milgram devised experiments that forced a choice: Do I remain true to my own standards or do I respond to others? That’s a dilemma we all face.

In Milgram’s experiments and their modern replications (Burger, 2009), participants were also torn. Should they respond to the pleas of the victim or the orders of the experimenter? Their moral sense warned them not to harm another. But that same sense also prompted them to obey the experimenter and to be a good research participant. With kindness and obedience on a collision course, obedience usually won.

These experiments demonstrated that strong social influences can make people conform to falsehoods or give in to cruelty. Milgram saw this as the most basic lesson of his work. “Ordinary people, simply doing their jobs, and without any particular hostility on their part, can become agents in a terrible destructive process” (1974, p. 6).

346

Using the foot-in-the-door effect, Milgram began with a little tickle of electricity and advanced step by step. In the minds of those throwing the switches, the small action became justified, making the next act tolerable.

In any society, great evils sometimes grow out of people’s acceptance of lesser evils. The Nazi leaders suspected that most German civil servants would resist shooting or gassing Jews directly. But they found them surprisingly willing to handle the paperwork of the Holocaust (Silver & Geller, 1978). Milgram found a similar reaction in his experiments. When he asked 40 men to give the learning test while someone else delivered the shocks, 93 percent agreed. Cruelty does not require devilish villains. All it takes is ordinary people corrupted by an evil situation. Ordinary students may follow orders to haze new members joining their group. Ordinary employees may follow orders to produce and market harmful products. Ordinary soldiers may follow orders to torture prisoners (Lankford, 2009).

In Jozefow and Le Chambon, as in Milgram’s experiments, those who resisted usually did so early. After the first acts of obedience or resistance, attitudes began to follow and justify behavior.

What have social psychologists learned about the power of the individual? Social control (the power of the situation) and personal control (the power of the individual) interact. Much as water dissolves salt but not sand, so rotten situations turn some people into bad apples while others resist (Johnson, 2007).

People do resist. When feeling pressured, some react by doing the opposite of what is expected (Brehm & Brehm, 1981). Rosa Parks’ refusal to sit at the back of the bus ignited the U.S. civil rights movement.

The power of one or two individuals to sway majorities is minority influence (Moscovici, 1985). In studies, one finding repeatedly stands out. When you are the minority, you are far more likely to sway the majority if you hold firmly to your position and don’t waffle. This tactic won’t make you popular, but it may make you influential, especially if your self-confidence stimulates others to consider why you react as you do. Even when a minority’s influence is not yet visible, people may privately develop sympathy for the minority position and rethink their views (Wood et al., 1994). The powers of social influence are enormous, but so are the powers of the committed individual.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 12.5

In psychology’s most famous obedience experiments, most participants obeyed an authority figure’s demands to inflict presumed life-threatening shocks on an innocent person. Social psychologist __________ __________ conducted these experiments.

Stanley Milgram

Question 12.6

In the obedience experiments, people were most likely to follow orders in four situations. What were those situations?

The Milgram studies showed that people were most likely to follow orders when (a) the person giving the orders was nearby and was a legitimate authority figure, (b) the authority figure was supported by a respected institution, (c) the victim was not nearby, and (d) there were no models for defiance.

Group Influence

12-6 How does the presence of others influence our actions, via social facilitation, social loafing, or deindividuation?

Imagine yourself standing in a room, holding a fishing pole. Your task is to wind the reel as fast as you can. On some occasions you wind in the presence of another participant who is also winding as fast as possible. Will the other’s presence affect your own performance?

In one of social psychology’s first experiments, Norman Triplett (1898) found that adolescents would wind a fishing reel faster in the presence of someone doing the same thing. He and later social psychologists studied how the presence of others affects our behavior. Group influences operate in such simple groups—one person in the presence of another—and in more complex groups.

Social Facilitation

Triplett’s finding—that our responses on an individual task are stronger in the presence of others—is called social facilitation. Later studies revealed that the presence of others sometimes helps and sometimes hurts performance (Guerin, 1986; Zajonc, 1965). Why? Because when others observe us, we become aroused, and this arousal amplifies our other reactions. It strengthens our most likely response—the correct one on an easy task, an incorrect one on a difficult task. Thus, when others observe us, we perform well-learned tasks more quickly and accurately. But on new and difficult tasks, we perform less quickly and accurately.

347

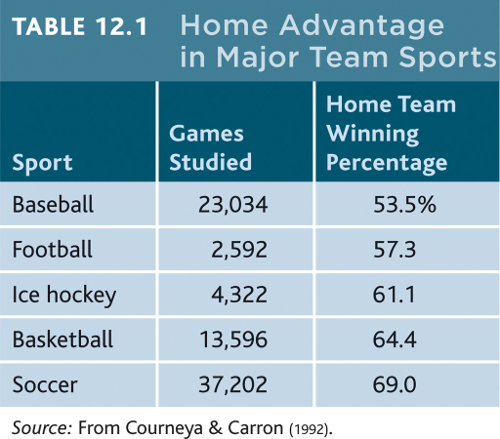

This effect helps explain the hometeam advantage. Studies of more than 80,000 college and professional athletic events in Canada, the United States, and England show that the home team advantage is real (TABLE 12.1). An enthusiastic audience seems to energize the home sports team. In about 6 in 10 games (somewhat fewer for baseball and football, somewhat more for basketball and soccer), home teams win.

The point to remember: What you do well, you are likely to do even better in front of an audience, especially a friendly audience. What you normally find difficult may seem all but impossible when you are being watched.

Social facilitation also helps explain a funny effect of crowding. Comedians and actors know that a “good house” is a full one. What they may not know is that crowding triggers arousal, which, as you have seen, strengthens other reactions. Comedy routines that are mildly amusing to people in an uncrowded room seem funnier in a densely packed room (Aiello et al., 1983; Freedman & Perlick, 1979). And when you seat participants close to one another, they like a friendly person even more, an unfriendly person even less (Schiffenbauer & Schiavo, 1976; Storms & Thomas, 1977). You can use this finding to increase the chances of lively interaction at your next gathering. Choose a room or set up seating that will just barely hold all your guests.

Social Loafing

Does the presence of others have the same arousal effect when we perform a task as a group? In a team tug-of-war, do we exert more than, less than, or the same amount of effort as in a one-on-one tug-of-war? If you said, “less than,” you’re right. In one experiment, students who believed three others were also pulling behind them exerted only 82 percent as much effort as when they knew they were pulling alone (Ingham et al., 1974). And consider what happened when blindfolded people seated in a group clapped or shouted as loud as they could while hearing (through headphones) other people clapping or shouting (Latané, 1981). In one round of noise-making, the participants believed the researchers could identify their individual sounds. In another round, they believed their clapping and shouting was blended with other people’s. When they thought they were part of a group effort, the participants produced about one-third less noise than when clapping “alone.”

This lessened effort is called social loafing (Jackson & Williams, 1988; Latané, 1981). Experiments in the United States, India, Thailand, Japan, China, and Taiwan have recorded social loafing on various tasks. It was especially common among men in individualist cultures (Karau & Williams, 1993). What causes social loafing? Three things:

- People acting as part of a group feel less accountable, so they worry less about what others think of them.

- Group members may not believe their individual contributions make a difference (Harkins & Szymanski, 1989; Kerr & Bruun, 1983).

- Loafing is its own reward. When group members share equally in the benefits regardless of how much they contribute, some may slack off. (If you’ve worked on group assignments, you’re probably already aware of this.) People who are not highly motivated, who don’t identify strongly with the group, may free ride on others’ efforts.

Deindividuation

We’ve seen that the presence of others can arouse people or it can make them feel less responsible. But sometimes the presence of others does both, triggering behavior that can range from a food fight to vandalism or rioting. This process of losing self-awareness and self-restraint is called deindividuation. It often occurs when group participation makes people feel aroused and anonymous. In one experiment, some female students dressed in Ku Klux Klan–style hoods that concealed their identity. Others in a control group did not wear the hoods. Those wearing hoods delivered twice as much electric shock to a victim (Zimbardo, 1970). (As in all such experiments, the “victim” did not actually receive the shocks.)

348

Deindividuation thrives, for better or for worse, in many different settings. The anonymity of Internet discussion boards and blog comment sections can unleash mocking or cruel words. Tribal warriors wearing face paints or masks have been more likely than those with exposed faces to kill, torture, or mutilate captured enemies (Watson, 1973). Internet trolls and bullies, who would never say “You’re a fraud” to someone’s face, will hide behind their online anonymity. When we shed self-awareness and self-restraint—whether in a mob, at a rock concert, at a ballgame, or at worship—we become more responsive to the group experience—bad or good.

Group Polarization

12-7 How can group interaction enable group polarization and groupthink?

Over time, differences between groups of college students tend to grow. If the first-year students at College X tend to be more artistic, and those at College Y tend to be more business-savvy, those differences will probably be even greater by the time they graduate.

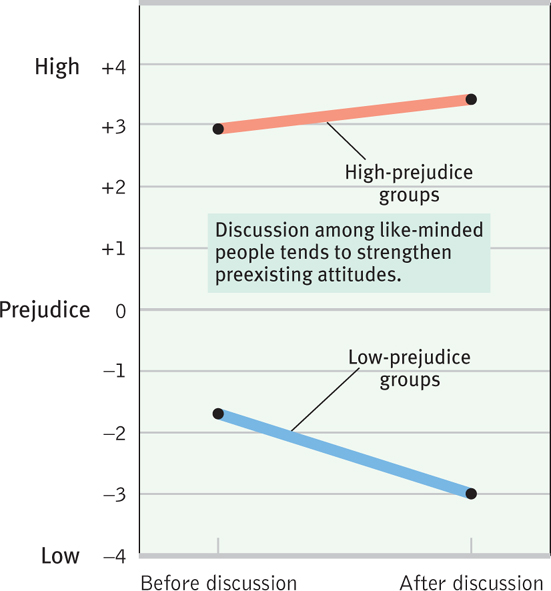

In each case, the beliefs and attitudes students bring to a group grow stronger as they discuss their views with others who share them. This process, called group polarization, can have positive results, as when low-prejudice students become even more accepting while discussing racial issues. It can also have negative results (FIGURE 12.4), as when high-prejudice students discuss racial issues and become more prejudiced (Myers & Bishop, 1970).

Researchers captured group polarization in a 2005 “Deliberation Day” experiment (Schkade et al., 2006). They chose a random sample of people from the voter rolls of liberal Boulder, Colorado. They then divided the sample into five-person groups to discuss global climate change, affirmative action, and same-sex civil unions. In Colorado Springs, the researchers followed the same procedure with its more conservative voters. After the discussions, those in Boulder had moved further left, and those in Colorado Springs further right.

The polarizing effect of interaction among like-minded people applies also to suicide terrorists. The terrorist mentality does not erupt suddenly on a whim (McCauley, 2002; McCauley & Segal, 1987; Merari, 2002). It usually begins slowly, among people who get together because of a grievance. As group members interact in isolation (sometimes with other “brothers” and “sisters” in camps), their views grow more and more extreme. Increasingly, they divide the world into “us” against “them” (Moghaddam, 2005; Qirko, 2004).

349

The Internet provides an easily accessible medium for group polarization. For more on this, see Thinking Critically About: The Internet as Social Amplifier.

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT

The Internet as Social Amplifier

I cut my eyeteeth in social psychology with experiments on group polarization—the tendency for face-to-face discussion to amplify group members’ existing opinions. Never then did I imagine the potential dangers, or the creative possibilities, of polarization in virtual groups.

Electronic communication and social networking have created virtual town halls where people can isolate themselves from those with different opinions. As the Internet connects the like-minded and pools their ideas, climate-change skeptics, UFO abductees, and conspiracy theorists find support for their shared ideas and suspicions. White supremacists may become more racist. Cyberbullies may become more abusive. And militia members may become violent. In the echo chambers of virtual worlds, as in the real world, separation + conversation = polarization.

But the Internet-as-social-amplifier can also work for good. Social networking sites connect friends and family members sharing common interests or coping with challenges. Peacemakers, cancer survivors, and bereaved parents can find strength and support from kindred spirits. By amplifying shared concerns and ideas, Internet-enhanced communication can also foster social ventures. (I know this personally from social networking with others with hearing loss to transform American assistive listening technology.)

The point to remember: By linking and magnifying the inclinations of like-minded people, the Internet can be very, very bad, but also very, very good.

Groupthink

So group interaction can influence our personal decisions. Can it also influence important national decisions? It can and it does. In one famous decision, it led to what is now known as the “Bay of Pigs fiasco.” President John F. Kennedy and his advisers decided in 1961 to invade Cuba with 1400 CIA-trained Cuban exiles. When the invaders were easily captured and quickly linked to the U.S. government, the president wondered in hind-sight, “How could I have been so stupid?”

Reading a historian’s account of the ill-fated blunder, social psychologist Irving Janis (1982) found some clues in the invasion’s decision-making procedures. The morale of the popular and recently elected president and his advisers was soaring. Their confidence was almost unlimited. To preserve the good feeling, group members with differing views kept quiet, especially after President Kennedy voiced his enthusiasm for the scheme. Since no one spoke strongly against the idea, everyone assumed the support was unanimous. Groupthink was at work: The desire for harmony had replaced realistic judgment.

Groupthink later contributed to the escalation of the Vietnam war, the Chernobyl nuclear reactor accident in Russia, and the U.S. space shuttle Challenger explosion (Esser & Lindoerfer, 1989; Reason, 1987). Most recently, it surfaced in U.S. discussions of the Iraq war, which was launched on the false idea that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction (WMD). The bipartisan U.S. Senate Intelligence Committee (2004) reported that “personnel involved in the Iraq WMD issue demonstrated several aspects of groupthink: examining few alternatives, selective gathering of information, pressure to conform within the group or withhold criticism, and collective rationalization.” This mode of thinking led analysts to interpret some evidence as proof of a WMD program and to “ignore or minimize evidence that Iraq did not have [WMD] programs.”

In the Iraq war discussions, groupthink was fed by overconfidence, conformity, self-justification, and group polarization. How can we prevent groupthink? Knowing that two heads are often better than one, leaders can welcome open debate, invite experts’ critiques of developing plans, and assign people to identify possible problems.

350

The point to remember: None of us is as smart as all of us, especially when we welcome open debate.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 12.7

What is social facilitation, and under what circumstances is it most likely to occur?

This improved performance in the presence of others is most likely to occur with a well-learned task, because the added arousal caused by an audience tends to strengthen the most likely response.

Question 12.8

People tend to exert less effort when working with a group than they would alone, which is called __________ __________.

social loafing

Question 12.9

You are organizing a meeting of fiercely competitive political candidates. To add to the fun, friends have suggested handing out masks of the candidates’ faces for supporters to wear. What effect might these masks trigger?

The anonymity provided by the masks, combined with the arousal of the competitive setting, might create deindividuation (lessened self-awareness and self-restraint).

Question 12.10

When like-minded groups discuss a topic, the existing opinions often grow stronger. This tendency is called __________ __________.

group polarization

Question 12.11

When a group’s desire for harmony overrides its realistic analysis of other options, ___________ has occurred.

groupthink