Social Relations

We have sampled how we think about and influence one another. Now we come to social psychology’s third focus—how we relate to one another. What causes us to harm or to help or to fall in love? How can we transform the closed fists of aggression into the open arms of compassion? We will ponder the bad and the good: from prejudice and aggression to attraction, altruism, and peacemaking.

We have sampled how we think about and influence one another. Now we come to social psychology’s third focus—how we relate to one another. What causes us to harm or to help or to fall in love? How can we transform the closed fists of aggression into the open arms of compassion? We will ponder the bad and the good: from prejudice and aggression to attraction, altruism, and peacemaking.

Prejudice

12-8 What are the three parts of prejudice, and how has prejudice changed over time?

Prejudice means “prejudgment.” It is an unfair negative attitude toward some group. The target of the prejudice is often a different cultural, ethnic, or gender group.

Prejudice is a three-part mixture of

- beliefs (called stereotypes).

- emotions (for example, hostility, envy, or fear).

- predispositions to action (to discriminate).

“Unhappily the world has yet to learn how to live with diversity.”

Pope John Paul II, Address to the United Nations, 1995

Some stereotypes may be at least partly accurate. If you presume that young men tend to drive faster than elderly women, you may be right. But to believe that obese people are gluttonous, and to feel dislike for an obese person, and to pass over all the obese people on a dating site is to be prejudiced. Prejudice is a negative attitude. Discrimination is a negative behavior.

Our ideas influence what we notice and how we interpret events. In one 1970s study, most White participants who saw a White man shoving a Black man said they were “horsing around.” When they saw a Black man shoving a White man, they interpreted the same act as “violent” (Duncan, 1976). The ideas we bring to a situation can color our perceptions.

How Prejudiced Are People?

To assess prejudice, we can observe what people say and what they do. What Americans say about gender and race has changed dramatically in the last 70 years. In 1937, one-third of Americans told Gallup pollsters they would vote for a qualified woman whom their party nominated for president. That number soared to 89 percent by 2007 (Gallup Brain, 2008; Jones & Moore, 2003). Nearly everyone now agrees that men and women should receive the same pay for doing the same job, and that children of all races should attend the same schools.

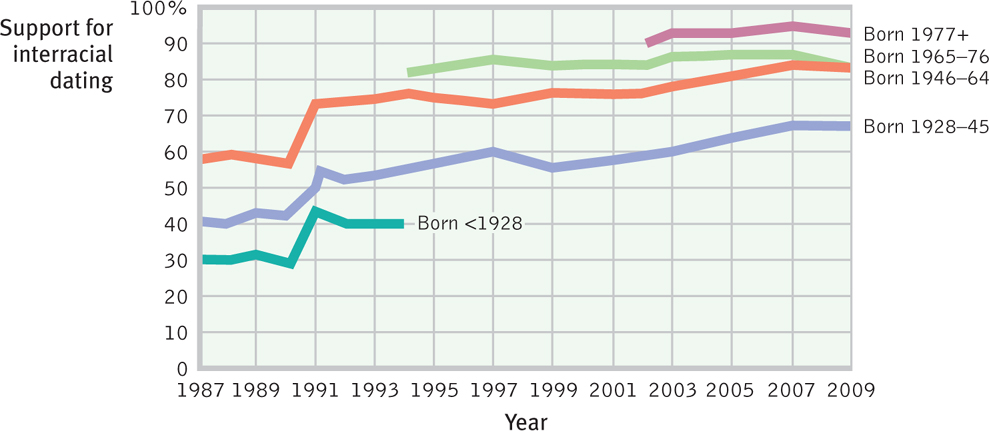

Support for all forms of racial contact, including interracial dating (FIGURE 12.5), has also dramatically increased. Among 18- to 29-year-old Americans, 9 in 10 now say they would be fine with a family member marrying someone of a different race (Pew, 2010).

Yet as open prejudice wanes, subtle prejudice lingers. As shown in FIGURE 12.5, Americans’ approval of interracial marriage has soared over the past half-century (Gallup surveys reported by Carroll, 2007). Yet many people admit that in socially intimate settings (dating, dancing, marrying) they would feel uncomfortable with someone of another race. Many Americans also say they would feel upset with someone making racist slurs. Actually, when hearing racist comments, many respond indifferently (Kawakami et al., 2009). Recent experiments illustrate that prejudice can be not only subtle but also automatic and unconscious (see Close-Up: Automatic Prejudice).

Sometimes it is not so subtle. When experimenters have sent thousands of resumes in response to employment ads, “Eric” has been more likely than “Hassan” to get a reply. “Emily” has received more replies than “Lakisha.” And those whose past activities included “Treasurer, Progressive and Socialist Alliance” received more replies than those who had been “Treasurer, Gay and Lesbian Alliance” (Agerström et al., 2012; Bertrand & Mullainathan, 2003; Drydakis, 2009).

In most places in the world, gays and lesbians cannot comfortably acknowledge who they are and whom they love (Katz-Wise & Hyde, 2012; United Nations, 2011). Gender prejudice and discrimination persist, too. Despite gender equality in intelligence scores, people have tended to perceive their fathers as more intelligent than their mothers (Furnham & Wu, 2008). In Saudi Arabia, women are still not allowed to drive. In Western countries, we still pay more to those (usually men) who care for our streets than to those (usually women) who care for our children. Worldwide, women have been more likely to live in poverty (Lipps, 1999). And among adults who cannot read, two-thirds are women (CIA, 2010).

351

Unwanted female infants are no longer left on a hillside to die of exposure, as was the practice in ancient Greece. Yet the normal male-to-female newborn ratio (105 to 100) hardly explains the world’s estimated 163 million (say that number slowly) “missing women” (Hvistendahl, 2011). In many places, sons are valued more than daughters. If men could choose their children’s gender, “we’d get a few decades of incredible football,” comedian Aaron Karo (2012) wryly suggested, but the human race would die out.

Social Roots of Prejudice

12-9 What factors contribute to the social roots of prejudice, and how does scapegoating illustrate the emotional roots of prejudice?

Why does prejudice arise? Social inequalities and social divisions are partly responsible.

C L O S E - U P

Automatic Prejudice

Again and again throughout this book, we have seen that the human mind processes thoughts, memories, and attitudes on two different tracks. Sometimes that processing is explicit—on the radar screen of our awareness. More often, it is implicit—below the radar, out of sight. Modern studies indicate that prejudice is often implicit, an automatic attitude that is more of an unthinking knee-jerk response than a decision. Consider these findings.

Implicit racial associations Even people who deny harboring racial prejudice may carry negative associations (Fisher & Borgida, 2012; Greenwald et al., 1998). For example, 9 in 10 White respondents took longer to identify pleasant words (such as peace and paradise) as “good” when the words were paired with Black-sounding names (such as Latisha and Darnell) rather than White-sounding names (such as Katie and Ian). Such tests are useful for studying automatic prejudice. But critics caution against using them to assess or label individuals as prejudiced (Blanton et al., 2006, 2007, 2009).

Race-influenced perceptions Our expectations influence our perceptions. Consider the shooting of an unarmed man in the doorway of his Bronx apartment building several years ago. The officers thought he had pulled a gun from his pocket. In fact, he had pulled out his wallet. Curious about this tragic killing of an innocent man, several research teams reenacted the situation (Correll et al., 2002, 2007; Greenwald et al., 2003; Sadler et al., 2012). They asked viewers to press buttons quickly to “shoot” or not shoot men who suddenly appeared on screen. Some of the on-screen men held a gun. Others held a harmless object, such as a flashlight or bottle. People (both Blacks and Whites, in one study) more often shot Black men holding the harmless object.

Reflexive bodily responses Even people who consciously express little prejudice may give off telltale signals as their body responds selectively to another person’s race. Neuroscientists can detect these signals when people look at images of White and Black faces. The viewers’ implicit prejudice shows up in different responses in their facial muscles and in their amygdala, an emotion-processing center (Cunningham et al., 2004; Eberhardt, 2005; Vanman et al., 2004).

Are you sometimes aware that you have feelings you would rather not have about other people? If so, remember this: It is what we do with our feelings that matters. By monitoring our feelings and actions, and by replacing old habits with new ones based on new friendships, we can free ourselves of prejudice.

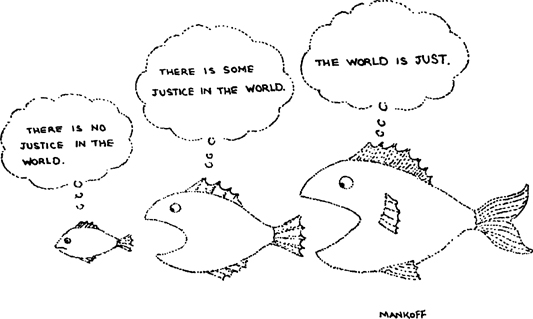

SOCIAL INEQUALITIES Some people have money, power, and prestige. Others do not. In this situation, the “haves” usually develop attitudes that justify things as they are. The just-world phenomenon assumes that good is rewarded and evil is punished. From this it is but a short leap to assume that those who succeed must be good and those who suffer must be bad. Such reasoning enables the rich to see both their own wealth and the misfortune of the poor as justly deserved.

352

Are women naturally unassertive but sensitive? Such stereotypes just happen to “justify” holding women responsible for the caretaking tasks they have traditionally performed (Hoffman & Hurst, 1990). In an extreme case, slave “owners” developed attitudes that they then used to “justify” slavery. They stereotyped the people they enslaved as being innately lazy, ignorant, and irresponsible. Stereotypes rationalize inequalities.

Victims of discrimination may react with either self-blame or anger (Allport, 1954). Either reaction can feed prejudice through the classic blame-the-victim dynamic. Do the circumstances of poverty breed a higher crime rate? If so, that higher crime rate can be used to justify discrimination against those who live in poverty.

US AND THEM: INGROUP AND OUTGROUP We have inherited our Stone Age ancestors’ need to belong—to live and love in groups. We cheer for our groups, kill for them, die for them. Indeed, we define who we are partly in terms of our groups. Through our social identities we associate ourselves with certain groups and contrast ourselves with others (Hogg, 1996; Turner, 1987). When Marc identifies himself as a man, an American, a political Independent, a Hudson Community College student, a Catholic, and a part-time letter carrier, he knows who he is, and so do we.

“All good people agree,

And all good people say

All nice people, like Us,

are We

And everyone else is They.”

Rudyard Kipling, “We and They,” 1926

Evolution prepared us, when meeting strangers, to make instant judgments: friend or foe? Those from our group, those who look like us, and also those who sound like us—with accents like our own—we instantly tend to like, from childhood onward (Gluszek & Dovidio, 2010; Kinzler et al., 2009). Mentally drawing a circle defines “us,” the ingroup. But the social definition of who we are also states who we are not. People outside that circle are “them,” the outgroup. An ingroup bias —a favoring of our own group—soon follows. Even forming us-them groups by tossing a coin creates this bias. In experiments, people have favored their own new group when dividing any rewards (Tajfel, 1982; Wilder, 1981).

Ingroup bias explains why active supporters of political parties may see what they expect to see (Cooper, 2010; Douthat, 2010). In the United States in the late 1980s, most Democrats believed inflation had risen under Republican president Ronald Reagan. (They were wrong: It had dropped.) In 2010, most Republicans believed that taxes had increased under Democrat president Barack Obama. (They were wrong: For most, they had decreased.)

Emotional Roots of Prejudice

Prejudice springs not only from the divisions of society but also from the passions of the heart. Scapegoat theory proposes that when things go wrong, finding someone to blame can provide an outlet for anger. Following the 9/11 terrorist attacks, negative stereotypes blossomed. Some outraged people lashed out at innocent Arab-Americans. Others called for eliminating Saddam Hussein, the Iraqi leader whom Americans had been grudgingly tolerating. “Fear and anger create aggression, and aggression against citizens of different ethnicity or race creates racism and, in turn, new forms of terrorism,” noted Philip Zimbardo (2001).

Evidence for the scapegoat theory of prejudice comes from two sources:

- Prejudice levels tend to be high among economically frustrated people.

- In experiments, a temporary frustration increases prejudice.

353

Students made to feel temporarily insecure have often restored their self-esteem by speaking badly of a rival school or another person (Cialdini & Richardson, 1980; Crocker et al., 1987). Those made to feel loved and supported have become more open to and accepting of others who differ (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2001).

Negative emotions nourish prejudice. When facing death, fearing threats, or experiencing frustration, we cling more tightly to our ingroup and our friends. The terror of death heightens patriotism. It also produces anger and aggression toward “them”—those who threaten our world (Pyszczynski et al., 2002, 2008).

Cognitive Roots of Prejudice

12-10 What are the cognitive roots of prejudice?

Prejudice springs from a culture’s divisions, the heart’s passions, and also from the mind’s natural workings. Stereotyped beliefs are a by-product of how we cognitively simplify the world.

FORMING CATEGORIES One way we simplify our world is to sort things into categories. A chemist sorts molecules into categories of “organic” and “inorganic.” Therapists categorize psychological disorders. All of us categorize people by race, with mixed-race people often assigned to their minority identity. Despite his mixed-race background and being raised by a White mother and White grandparents, President Barack Obama has been perceived by White Americans as Black. Researchers believe this happens because, after learning the features of a familiar racial group, the observer’s selective attention is drawn to the distinctive features of the less-familiar minority. In one study, New Zealanders viewed images of blended Chinese-Caucasian faces (Halberstadt et al., 2011). Some participants were of European descent; others were of Chinese descent. Those of European descent more readily classified ambiguous faces as Chinese (see FIGURE 12.6 ).

When we categorize people into groups, we often overestimate their similarities. “They”—the members of that other social or ethnic group—seem to look alike (Rhodes & Anastasi, 2012; Young et al., 2012). In personality and attitudes, too, they seem more alike than they really are, while “we” differ from one another (Bothwell et al., 1989). This greater recognition for own-race faces is called the other-race effect (also called the cross-race effect or own-race bias). It emerges during infancy, between 3 and 9 months of age (Kelly et al., 2007).

REMEMBERING VIVID CASES Cognitive psychologists tell us that we often judge the likelihood of events by recalling vivid cases that readily come to mind. In a classic experiment, researchers showed two groups of student volunteers lists containing information about 50 men (Rothbart et al., 1978). The first group’s list included 10 men arrested for nonviolent crimes, such as forgery. The second group’s list included 10 men arrested for violent crimes, such as assault. Later, both groups were asked how many men on their list had committed any sort of crime. The second group overestimated the number. Vivid (violent) cases are readily available to our memory and feed our stereotypes (FIGURE 12.7) .

354

BELIEVING THE WORLD IS JUST As noted earlier, people often justify their prejudices by blaming the victims. If the world is just, “people must get what they deserve.” As one German civilian is said to have remarked when visiting the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp shortly after World War II, “What terrible criminals these prisoners must have been to receive such treatment.”

People have a basic tendency to justify their culture’s social systems (Jost et al., 2009; Kay et al., 2009). We’re inclined to see the way things are as the way they ought to be. This natural conservatism makes it difficult to legislate major social changes, such as civil rights laws or Social Security or health care reform. But once such policies are in place, our “system justification” tends to preserve them.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 12.12

When a prejudiced attitude causes us to blame an innocent person for our problems, we have used that person as a ____________

scapegoat

Aggression

12-11 What biological factors predispose us to be aggressive?

The most destructive force in our social relations is aggression. In psychology, aggression is any verbal or physical behavior intended to hurt or destroy, whether it is passing along a vicious rumor or engaging in a physical attack.

Aggressive behavior emerges when biology interacts with experience. For a gun to fire, the trigger must be pulled. With some people, as with hair-trigger guns, it doesn’t take much to trip an explosion. Let’s look first at some biological factors that influence our thresholds for aggressive behavior. Then we’ll turn to the psychological and social-cultural factors that pull the trigger.

The Biology of Aggression

Is aggression an unlearned instinct? The wide variation from culture to culture, era to era, and person to person argues against that idea. But biology does influence aggression at three levels—genetic, biochemical, and neural.

GENETIC INFLUENCES Genes influence aggression. We know this because animals have been bred for aggressiveness—sometimes for sport, sometimes for research. The effect of genes also appears in human twin studies (Miles & Carey, 1997; Rowe et al., 1999). If one identical twin admits to “having a violent temper,” the other twin will often independently admit the same. Fraternal twins are much less likely to respond similarly. Researchers continue to search for genetic markers, or predictors, in those who commit the most violence. One is already well known and is carried by half the human race: the Y chromosome.

BIOCHEMICAL INFLUENCES Our genes engineer our individual nervous systems, which operate electrochemically. The hormone testosterone, for example, circulates in the bloodstream and influences the neural systems that control aggression. A raging bull becomes a gentle Ferdinand when castration reduces its testosterone level. The same is true of mice. When injected with testosterone, gentle, castrated mice once again become aggressive.

In humans, high testosterone is associated with irritability, assertiveness, impulsiveness, and low tolerance for frustration. These qualities make people somewhat more prone to aggressive responses when provoked or when competing for status (Dabbs et al., 2001b; McAndrew, 2009; Montoya et al., 2012). Among both teenage boys and adult men, high testosterone levels have been linked with delinquency, hard drug use, and aggressive-bullying responses to frustration (Berman et al., 1993; Dabbs & Morris, 1990; Olweus et al., 1988). Drugs that sharply reduce testosterone levels subdue men’s aggressive tendencies. As men age, their testosterone levels—and their aggressiveness—diminish. Hormonally charged, aggressive 17-year-olds mature into hormonally quieter and gentler 70-year-olds.

In the last 40 years in the United States, well over 1 million people—more than all deaths in all wars in American history—have been killed by firearms in nonwar settings. Compared with people of the same sex, race, age, and neighborhood, those who keep a gun in the home (ironically, often for protection) are almost three times more likely to be murdered in the home. Nearly always, the shooter is a family member or close acquaintance. For every self-defense use of a gun in the home, there have been 4 unintentional shootings, 7 criminal assaults or homicides, and 11 attempted or completed suicides.

(Kellermann et al., 1993, 1997, 1998; see also Branas et al., 2009)

Another drug that sometimes circulates in the bloodstream—alcohol—also unleashes aggressive responses to frustration. Aggression-prone people are more likely to drink, and when intoxicated they are more likely to become violent (White et al., 1993). National crime data indicate that 73 percent of Russian homicides and 57 percent of U.S. homicides were influenced by alcohol (Landberg & Norström, 2011). Alcohol’s effects are both biological and psychological. Just thinking you’ve been drinking alcohol can increase aggression (Bègue et al., 2009). But so, too, does unknowingly drinking an alcohol-laced beverage.

355

NEURAL INFLUENCES There is no one spot in the brain that controls aggression. Aggression is a complex behavior, and it occurs in particular contexts. But animal and human brains have neural systems that, given provocation, will either inhibit or facilitate aggression (Denson, 2011; Moyer, 1983; Wilkowski et al., 2011). Consider:

- Researchers implanted a radio-controlled electrode in the brain of the domineering leader of a caged monkey colony. The electrode was in an area that, when stimulated, inhibits aggression. When researchers placed the control button for the electrode in the colony’s cage, one small monkey learned to push it every time the boss became threatening.

- A neurosurgeon implanted an electrode in the brain of a mild-mannered woman to diagnose a disorder. The electrode was in her amygdala, within her limbic system. Because the brain has no sensory receptors, she did not feel the stimulation. But at the flick of a switch, she snarled, “Take my blood pressure. Take it now,” then stood up and began to strike the doctor.

- Studies of violent criminals have revealed diminished activity in the frontal lobes, which help control impulses. If the frontal lobes are damaged, inactive, disconnected, or not yet fully mature, aggression may be more likely (Amen et al., 1996; Davidson et al., 2000; Raine, 1999, 2005).

Psychological and Social-Cultural Influences on Aggression

12-12 What psychological and social-cultural factors may trigger aggressive behavior?

Biological factors create the hair trigger for aggression. But what psychological and social-cultural factors pull that trigger?

AVERSIVE EVENTS Suffering sometimes builds character. In laboratory experiments, however, those made miserable have often made others miserable (Berkowitz, 1983, 1989). This reaction is called the frustration-aggression principle. Frustration creates anger, which can spark aggression. One Major League Baseball analysis of 27,667 hit-by-pitch incidents between 1960 and 2004 revealed this link (Timmerman, 2007). Pitchers were most likely to hit batters when

- they had been frustrated by the previous batter hitting a home run.

- the current batter hit a home run the last time at bat.

- a teammate had been hit by a pitch in the previous half-inning.

Other aversive stimuli—hot temperatures, physical pain, personal insults, foul odors, cigarette smoke, crowding, and a host of others—can also trigger anger. When people get overheated, they think, feel, and act more aggressively. Simply thinking about words related to hot temperatures is enough to increase hostile thoughts (DeWall & Bushman, 2009). In baseball games, the number of hit batters rises with the temperature (Reifman et al., 1991; see FIGURE 12.8 ). And in the wider world, violent crime and spousal abuse rates have been higher during hotter years, seasons, months, and days (Anderson et al., 1997). One projection, based on the available data, estimates that global warming of 4 degrees Fahrenheit (about 2 degrees Celsius) could induce tens of thousands of additional assaults and murders (Anderson et al., 2000, 2011). And that’s before the added violence inducement from climate-change-related drought, poverty, food insecurity, and migration.

356

REINFORCEMENT, MODELING, AND SELF-CONTROL Aggression may naturally follow aversive events, but learning can alter natural reactions. As Chapter 6 points out, we learn when our behavior is reinforced, and we learn by watching others. Children whose aggression successfully intimidates other children may become bullies. Animals that have successfully fought to get food or mates become increasingly ferocious. To foster a kinder, gentler world, we had best model and reward sensitivity and cooperation from an early age, perhaps by training parents to discipline without modeling violence.

Parents of delinquent youth frequently cave in to (and thus reward) their children’s tears and temper tantrums. Then, frustrated, they discipline with beatings (Patterson et al., 1982, 1992). Parent-training programs often advise parents to avoid modeling violence by screaming and hitting. Instead, parents should reinforce desirable behaviors and frame statements positively. (“When you finish loading the dishwasher, you can go play,” rather than “If you don’t load the dishwasher, there’ll be no playing.”)

“Why do we kill people who kill people to show that killing people is wrong?”

National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty, 1992

Self-control curbs aggressive and criminal behavior. Alas, physical and mental challenges, such as exhaustion and food and sleep deprivation, often deplete our self-control (Vohs et al., 2011). Picture yourself after a long, challenging day at school or work, or after missing a meal or when sleep deprived. Might you, without realizing what’s happening, begin to snap at your friends or partner?

Poor self-control is “one of the strongest known correlates of crime” (Pratt & Cullen, 2000, p. 952). To foster self-control, one aggression-replacement program worked with juvenile offenders and gang members and their parents. It taught both generations new ways to control anger, and more thoughtful approaches to moral reasoning (Goldstein et al., 1998). The result? The youths’ rearrest rates dropped.

Different cultures model, reinforce, and evoke different tendencies toward violence. For example, U.S. men are less approving of male-to-female violence between romantic partners than are men from India, Japan, and Kuwait (Nayak et al., 2003). Crime rates have also been higher and average happiness has been lower in times and places marked by a great income gap between rich and poor (Messias et al., 2011; Oishi et al., 2011; Wilkinson & Pickett, 2009). In the United States, high rates of violence and youth imprisonment have been found in cultures and families with minimal or no father care (Harper & McLanahan, 2004; Triandis, 1994).

MEDIA MODELS FOR VIOLENCE Parents are not the only aggression models. In the United States and else-where, TV shows, films, and video games offer supersized portions of violence. Repeatedly viewing on-screen violence tends to make us less sensitive to cruelty (Montag et al., 2012). It also primes us to respond aggressively when provoked. And it teaches us social scripts—culturally provided mental files for how to act. When we find ourselves in new situations, uncertain how to behave, we rely on social scripts. After watching so many action films, adolescent boys may acquire a script that plays in their head when they face real-life conflicts. Challenged, they may “act like a man” by intimidating or eliminating the threat. More than 100 studies together confirm that people sometimes imitate what they’ve viewed. Watching risk-glorifying behaviors (dangerous driving, extreme sports, unprotected sex) increases viewers’ real-life risktaking (Fischer et al., 2011).

357

Music lyrics also write social scripts. In experiments, German university men who listened to woman-hating song lyrics administered the most hot chili sauce to a woman. They also recalled more negative feelings and beliefs about women. Man-hating song lyrics had a similar effect on the aggressive behavior of women listeners (Fischer & Greitemeyer, 2006).

Sexual scripts depicted in X-rated films are often toxic. People heavily exposed to televised crime perceive the world as more dangerous. People heavily exposed to pornography see the world as more sexual. Repeatedly watching X-rated films, even nonviolent films, has many effects (Kingston et al., 2009). One’s own partner seems less attractive (Chapter 4). Extramarital sex seems less troubling (Zillmann, 1989). Women’s friendliness seems more sexual. Sexual aggression seems less serious (Harris, 1994).

In one experiment, undergraduates viewed six brief, sexually explicit films each week for six weeks (Zillmann & Bryant, 1984). A control group viewed films with no sexual content during the same six-week period. Three weeks later, both groups read a newspaper report about a man convicted of raping a hitchhiker and were asked to suggest an appropriate prison term. Sentences recommended by those viewing the sexually explicit films were only half as long as the sentences recommended by the control group.

Research on the effects of violent versus nonviolent erotic films indicates that it’s not the sexual content of films that most directly affects men’s aggression against women. It’s the sexual violence, whether in R-rated slasher films or X-rated films. A statement by 21 social scientists noted, “Pornography that portrays sexual aggression as pleasurable for the victim increases the acceptance of the use of coercion in sexual relations” (Surgeon General, 1986). Contrary to much popular opinion, viewing such scenes does not provide an outlet for bottled-up impulses. Rather, “in laboratory studies measuring short-term effects, exposure to violent pornography increases punitive behavior toward women.”

To a lesser extent, nonviolent pornography can also influence aggression. One set of studies exploring pornography’s effects on aggression against relationship partners found that pornography consumption predicted both self-reported aggression and laboratory noise blasts to their partner (Lambert et al., 2011). Abstaining from customary pornography consumption decreased aggression. Abstaining from their favorite food did not.

DO VIOLENT VIDEO GAMES TEACH SOCIAL SCRIPTS FOR VIOLENCE? Experiments in North America, Western Europe, Singapore, and Japan indicate that playing positive games produces positive effects (Gentile et al., 2009; Greitemeyer & Osswald, 2010). For example, playing Lemmings, where a goal is to help others, increases real-life helping. So, might a parallel effect occur after playing games that enact violence? Violent video games became an issue for public debate after teenagers in more than a dozen places seemed to mimic the carnage in the shooter games they had so often played (Anderson, 2004a).

In 2002, two Grand Rapids, Michigan, teens and a man in his early twenties spent part of a night drinking beer and playing Grand Theft Auto III. Using simulated cars, they ran down pedestrians, then beat them with fists, leaving a bloody body behind (Kolker, 2002). These same teens and man then went out for a real drive. Spotting a 38-year-old man on a bicycle, they ran him down with their car, got out, stomped and punched him, and returned home to play the game some more. (The victim, a father of three, died six days later.)

Such violent mimicry causes some to wonder: What will be the effect of actively role-playing aggression? Will young people become less sensitive to violence and more open to violent acts? Nearly 400 studies of 130,000 people offer an answer, report some researchers (Anderson et al., 2010). Video games can prime aggressive thoughts, decrease empathy, and increase aggression. University men who spend the most hours playing violent video games have also tended to be the most physically aggressive (Anderson & Dill, 2000). (For example, they more often acknowledged having hit or attacked someone else.) And people randomly assigned to play a game involving bloody murders with groaning victims (rather than to play nonviolent Myst) became more hostile. On a follow-up task, they also were more likely to blast intense noise at a fellow student.

358

Studies of young adolescents reveal that those who play a lot of violent video games see the world as more hostile (Gentile, 2009). Compared with nongaming kids, they get into more arguments and fights and get worse grades.

Ah, but is this merely because naturally hostile kids are drawn to such games? Apparently not. Comparisons of gamers and nongamers who scored low in hostility revealed a difference in the number of fights they reported. Almost 4 in 10 violent-game players had been in fights. Only 4 in 100 of the nongaming kids reported fights (Anderson, 2004a). Some researchers believe that, due partly to the more active participation and rewarded violence of game play, violent video games have even greater effects on aggressive behavior and cognition than do violent TV shows and movies (Anderson & Warburton, 2012).

Other researchers are unimpressed by such findings (Ferguson & Kilburn, 2010; Ferguson et al., 2011). They note that from 1996 to 2006, youth violence was declining while video game sales were increasing, and that other factors—depression, family violence, peer influence—better predict aggression. Moreover, some point out that avid game players are quick and sharp: They develop speedy reaction times and enhanced visual skills (Dye et al., 2009; Green et al., 2010). The focused fun of game playing can satisfy basic needs for a sense of competence, control, and social connection (Przbylski et al., 2010). In 2011, a U.S. Supreme Court decision overturned a California state law that banned violent video game sales to children (modeled after the bans on sales of sexually explicit materials to children). The First Amendment’s free speech guarantee protects even offensive games, said the court’s majority, which was unpersuaded by the evidence of harm. So, the debate continues.

* * *

To sum up, research reveals biological, psychological, and social-cultural influences on aggressive behavior. Complex behaviors, including violence, have many causes, making any single explanation an oversimplification. Asking what causes violence is therefore like asking what causes cancer. Those who study the effects of asbestos exposure on cancer rates may remind us that asbestos is indeed a cancer cause, but it is only one among many. Like so much else, aggression is a biopsychosocial phenomenon.

A happy concluding note: Historical trends suggest that the world is increasingly nonviolent (Pinker, 2011). That people vary over time and place reminds us that environments differ. Yesterday’s plundering Vikings have become today’s peace-promoting Scandinavians. Like all behavior, aggression arises from the interaction of persons and situations.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 12.13

What psychological, biological, and social-cultural influences interact to produce aggressive behaviors?

Our biology (our genes, biochemistry, and neural systems—including testosterone and alcohol levels) influences our tendencies to be aggressive. Psychological factors (such as frustration, previous rewards for aggressive acts, and observation of others’ aggression) can trigger any aggressive tendencies we may have. Social influences, such as exposure to violent media and cultural factors, can also affect our aggressive responses.

Attraction

Pause a moment and think about your relationships with two people—a close friend, and someone who has stirred in you feelings of romantic love. These special sorts of attachments help us cope with all other relationships. What is the psychological chemistry that binds us together? Social psychology suggests some answers.

The Psychology of Attraction

12-13 Why do we befriend or fall in love with some people but not others?

We endlessly wonder how we can win others’ affection and what makes our own affections flourish or fade. Does familiarity breed contempt or affection? Do birds of a feather flock together, or do opposites attract? Is beauty only skin deep, or does attractiveness matter greatly? To explore these questions, let’s consider three ingredients of our liking for one another: proximity, physical attractiveness, and similarity.

PROXIMITY Before friendships become close, they must begin. Proximity—geographic nearness—is friendship’s most powerful predictor. Being near another person gives us opportunities for aggression, but much more often it breeds liking. Study after study reveals that people are most inclined to like, and even to marry, those who are nearby. We are drawn to those who live in the same neighborhood, sit nearby in class, work in the same office, share the same parking lot, eat in the same dining hall. Look around. Mating starts with meeting. (For a look at modern ways to connect people not in physical proximity, see Close-Up: Online Matchmaking and Speed Dating.)

359

Proximity breeds liking partly because of the mere exposure effect. Repeated exposure to novel stimuli increases our liking for them. This applies to nonsense syllables, musical selections, geometric figures, Chinese characters, human faces, and the letters of our own name (Moreland & Zajonc, 1982; Nuttin, 1987; Zajonc, 2001). People are even somewhat more likely to marry someone whose first or last name resembles their own (Jones et al., 2004).

So, within certain limits, familiarity breeds fondness (Bornstein, 1989, 1999). Researchers demonstrated this by having four equally attractive women silently attend a 200-student class for zero, 5, 10, or 15 class sessions (Moreland & Beach, 1992). At the end of the course, students were shown slides of each woman and asked to rate her attractiveness. The most attractive? The ones they’d seen most often. These ratings would come as no surprise to the young Taiwanese man who wrote more than 700 letters to his girlfriend, urging her to marry him. She did marry—the mail carrier (Steinberg, 1993).

PHYSICAL ATTRACTIVENESS So proximity offers contact. What most affects our first impressions? The person’s sincerity? Intelligence? Personality? The answer is physical appearance. This finding is unnerving for most of us who were taught that “beauty is only skin deep” and that “appearances can be deceiving.”

C L O S E - U P

Online Matchmaking and Speed Dating

If you have not found a romantic partner in your immediate proximity, why not cast a wider net? Each year, an estimated 30 million people search for love on one of the 1500 online dating services (Ellin, 2009). Online matchmaking seems to work mostly by expanding the pool of potential mates (Finkel et al., 2012a,b).

How effective are Internet matchmaking services? Published research is sparse. But here’s a surprising finding: Compared with relationships formed in person, Internet-formed friendships and romantic relationships are, on average, more likely to last beyond two years (Bargh et al., 2002, 2004; McKenna & Bargh, 1998, 2000; McKenna et al., 2002). In one study, people disclosed more, with less posturing, to those whom they met online. When chatting online with someone for 20 minutes, they felt more liking for that person than they did for someone they had met and talked with face to face. This was true even when (unknown to them) it was the same person! Internet friendships often feel as real and important to people as in-person relationships. Small wonder that one survey found a leading online matchmaker enabling more than 500 U.S. marriages a day (Harris Interactive, 2010). By one estimate, online dating now is responsible for about a fifth of U.S. marriages (Crosier et al., 2012).

Dating sites collect trait information, but that accounts for only a thin slice of what makes for successful long-term relationships. What matters more, say researchers, is what emerges only after two people get to know each other, such as how they communicate and resolve disagreements (Finkel et al., 2012a,b). Skeptics are calling for controlled studies. To establish that some matchmaking secret sauce does actually work, they say, experiments need to match people by either using the data sites’ matchmaking formulas or not. And, of course, the participants should not know the basis of their match.

Speed dating pushes the search for romance into high gear. In a process pioneered by a matchmaking Jewish rabbi, people meet a succession of would-be partners, either in person or via webcam (Bower, 2009). After a 3- to 8-minute conversation, people move on to the next person. (In an in-person meeting, one partner—usually the woman—remains seated and the other circulates.) Those who want to meet again can arrange for future contacts. For many participants, 4 minutes is enough time to form a feeling about a conversational partner and to register whether the partner likes them (Eastwick & Finkel, 2008a,b).

Researchers have quickly realized that speed dating offers a unique opportunity for studying influences on our first impressions of potential romantic partners. Among recent findings are these:

- Men are more transparent. Observers (male or female) watching videos of speed dating can read a man’s level of romantic interest more accurately than a woman’s (Place et al., 2009).

- Given more options, people make more superficial choices. They focus on more easily assessed characteristics, such as height and weight (Lenton & Francesconi, 2010, 2012). This was true even when researchers controlled for time spent with each partner.

- Men wish for future contact with more of their speed dates; women tend to be more choosy. This gender difference disappears if the conventional roles are reversed, so that men stay seated while women circulate (Finkel & Eastwick, 2009).

360

In one early study, researchers randomly matched new students for a Welcome Week dance (Walster et al., 1966). Before the dance, the researchers gave each student a battery of personality and aptitude tests, and they rated each student’s level of physical attractiveness. On the night of the blind date, the couples danced and talked for more than two hours and then took a brief break to rate their dates. What determined whether they liked each other? Only one thing seemed to matter: appearance. Both the men and the women liked good-looking dates best. Women are more likely than men to say that another’s looks don’t affect them (Lippa, 2007). But studies show that a man’s looks do affect women’s behavior (Feingold, 1990; Sprecher, 1989; Woll, 1986). Speed-dating experiments confirm that attractiveness influences first impressions for both sexes (Belot & Francesconi, 2006; Finkel & Eastwick, 2008).

Physical attractiveness also predicts how often people date and how popular they feel. We don’t assume that attractive people are more compassionate, but we do perceive them as healthier, happier, more sensitive, more successful, and more socially skilled (Eagly et al., 1991; Feingold, 1992; Hatfield & Sprecher, 1986). Attractive, well-dressed people have been more likely to make a favorable impression on potential employers, and they have tended to be more successful in their jobs (Cash & Janda, 1984; Langlois et al., 2000; Solomon, 1987). There is a premium for beauty in the workplace, and a penalty for plainness or obesity (Engemann & Owyang, 2005).

Judging from their gazing times, even babies seem to prefer attractive over unattractive faces (Langlois et al., 1987). So do some blind people. University of Birmingham professor John Hull (1990, p. 23) discovered this after going blind himself. A colleague’s remarks about a woman’s beauty would strangely affect his feelings. He found this “deplorable. What can it matter to me what sighted men think of women…yet I do care what sighted men think, and I do not seem able to throw off this prejudice.”

For those of us who find the importance of looks unfair and short-sighted, two other findings may be reassuring. First, people’s attractiveness has been found to be surprisingly unrelated to their self-esteem and happiness (Diener et al., 1995; Major et al., 1984). Unless we have just compared ourselves with superattractive people, few of us (thanks, perhaps, to the mere exposure effect) view ourselves as unattractive (Thornton & Moore, 1993). Second, strikingly attractive people are sometimes suspicious that praise for their work may simply be a reaction to their looks. Less attractive people have been more likely to accept praise as sincere (Berscheid, 1981).

Beauty is in the eye of the culture. Hoping to look attractive, people across the globe have pierced and tattooed various body parts, lengthened their necks, bound their feet, and dyed or painted their skin and hair. Cultural ideals also change over time. In the United States, the soft, voluptuous Marilyn Monroe ideal of the 1950s has been replaced by today’s lean yet busty ideal.

If we’re not born attractive, we may try to buy beauty. Americans now spend more on beauty supplies than on education and social services combined. Still not satisfied, millions undergo plastic surgery, teeth capping and whitening, Botox skin smoothing, and laser hair removal (ASPS, 2010).

Do any aspects of attractiveness cross place and time? Yes. As we noted in Chapter 4, men in many cultures, from Australia to Zambia, judge women as more attractive if they have a youthful, fertile appearance, suggested by a low waist-to-hip ratio (Karremans et al., 2010; Perilloux et al., 2010; Platek & Singh, 2010). Women feel attracted to healthy-looking men, but especially—and the more so when ovulating—to those who seem mature, dominant, masculine, and wealthy (Gallup & Frederick, 2010; Gangestad et al., 2010). But faces matter, too. When people separately rate opposite-sex faces and bodies, the face tends to be the better predictor of overall physical attractiveness (Currie & Little, 2009; Peters et al., 2007).

Percentage of Men and Women Who “Constantly Think About Their Looks”

| Men | Women | |

| Canada | 18% | 20% |

| United States | 17 | 27 |

| Mexico | 40 | 45 |

| Venezuela | 47 | 65 |

From Roper Starch survey, reported by McCool (1999).

Our feelings also influence our attractiveness judgments. Imagine two people: One is honest, humorous, and polite. The other is rude, unfair, and abusive. Which one is more attractive? Most people perceive the person with the appealing traits as more attractive (Lewandowski et al., 2007). Or imagine being paired with an opposite-sex stranger who listened well to your self-disclosures (rather than seeming not tuned into your thoughts and feelings). If you are heterosexual, might you feel a twinge of sexual attraction toward that person? Student volunteers did, in several experiments (Birnbaum & Reis, 2012). Our feelings influence our perceptions.

361

In a Rodgers and Hammerstein musical, Prince Charming asks Cinderella, “Do I love you because you’re beautiful, or are you beautiful because I love you?” Chances are it’s both. As we see our loved ones again and again, we notice their physical imperfections less, and their attractiveness grows more obvious (Beaman & Klentz, 1983; Gross & Crofton, 1977). Shakespeare said it in A Midsummer Night’s Dream: “Love looks not with the eyes, but with the mind.” Come to love someone and watch beauty grow.

SIMILARITY So you’ve met someone, and your appearance has made a decent first impression. What now influences whether you will become friends? As you get to know each other, will the chemistry be better if you are opposites or if you are alike?

© Danita Delimont/Alamy

Ingram Publishing/Jupiter Images

It makes a good story—extremely different types liking or loving each other: Frog and Toad in Arnold Lobel’s books, Edward and Bella in the Twilight series. The stories delight us by expressing what we seldom experience, for in real life, opposites retract (Rosenbaum, 1986). Birds that flock together usually are of a feather. Compared with randomly paired people, friends and couples are far more likely to share attitudes, beliefs, and interests (and, for that matter, age, religion, race, education, intelligence, smoking behavior, and economic status). Journalist Walter Lippmann was right to suppose that love lasts “when the lovers love many things together, and not merely each other.”

Proximity, attractiveness, and similarity are not the only forces that influence attraction. We also like those who like us. This is especially so when our self-image is low. When we believe someone likes us, we feel good and respond warmly. Our warm response in turn leads them to like us even more (Curtis & Miller, 1986). To be liked is powerfully rewarding.

Indeed, all the findings we have considered so far can be explained by a simple reward theory of attraction. We will like those whose behavior is rewarding to us, and we will continue relationships that offer more rewards than costs. When people live or work in close proximity with us, it costs less time and effort to develop the friendship and enjoy its benefits. When people are attractive, they are aesthetically pleasing, and associating with them can be socially rewarding. When people share our views, they reward us by confirming our own.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 12.14

People tend to marry someone who lives or works nearby. This is an example of proximity and the __________ __________ __________ in action.

mere exposure effect

Question 12.15

How does being physically attractive influence others’ perceptions?

Being physically attractive tends to elicit positive first impressions. People tend to assume that attractive people are healthier, happier, and more socially skilled than others are.

Romantic Love

12-14 How does romantic love typically change as time passes?

Sometimes people move from first impressions, to friendship, to the more intense, complex, and mysterious state of romantic love. If love endures, temporary passionate love will mellow into a lingering companionate love (Hatfield, 1988).

PASSIONATE LOVE A key ingredient of passionate love is arousal. The two-factor theory of emotion (Chapter 9) can help us understand this intense, positive state of feeling fully absorbed in another (Hatfield, 1988). That theory makes two assumptions:

- Emotions have two ingredients—physical arousal and cognitive appraisal.

- Arousal from any source can enhance an emotion, depending on how we interpret and label the arousal.

In one famous experiment, researchers studied people crossing two bridges above British Columbia’s rocky Capilano River (Dutton & Aron, 1974, 1989). One, a swaying footbridge, was 230 feet above the rocks. The other was low and solid. The researchers had an attractive young woman stop men coming off each bridge and ask their help in filling out a short questionnaire. She then offered her phone number in case they wanted to hear more about her project. Which men accepted the number and later called the woman? Far more of those who had just crossed the high bridge—which left their hearts pounding. To experience a stirred-up state and to associate some of that feeling with a desirable person is to experience the pull of passion. Adrenaline makes the heart grow fonder. Sexual desire + a growing attachment = the passion of romantic love (Berscheid, 2010).

362

COMPANIONATE LOVE Passionate romantic love seldom endures. The intense absorption in the other, the thrill of the romance, the giddy “floating on a cloud” feeling typically fade. Are the French correct in saying that “love makes the time pass and time makes love pass”? The evidence indicates that, as love matures, it becomes a steadier companionate love—a deep, affectionate attachment (Hatfield, 1988). Like a passing storm, the flood of passion-feeding hormones (testosterone, dopamine, adrenaline) gives way. But another hormone, oxytocin, remains, supporting feelings of trust, calmness, and bonding with the mate. In the most satisfying of marriages, attraction and sexual desire endure, minus the obsession of early-stage romance (Acevedo & Aron, 2009).

There may be adaptive wisdom to this shift from passion to attachment (Reis & Aron, 2008). Passionate love often produces children, whose survival is aided by the parents’ waning obsession with one another. Failure to appreciate passionate love’s limited half-life can doom a relationship (Berscheid et al., 1984). Indeed, recognizing the short duration of passionate love, some societies judge such feelings to be a poor reason for marrying. Better, these cultures say, to choose (or have someone choose for you) a partner who shares your background and interests. Non-Western cultures, where people rate love less important for marriage, do have lower divorce rates (Levine et al., 1995). Do you think you could be happy in a marriage someone else arranged for you, by matching you with someone who shared your interests and traits? Many people in many cultures around the world live seemingly happy lives in such marriages.

“When two people are under the influence of the most violent, most insane, most delusive, and most transient of passions, they are required to swear that they will remain in that excited, abnormal, and exhausting condition continuously until death do them part.”

George Bernard Shaw, “Getting Married,” 1908

One key to a satisfying and enduring relationship is equity, as both partners receive in proportion to what they give (Gray-Little & Burks, 1983; Van Yperen & Buunk, 1990). In one national survey, “sharing household chores” ranked third, after “faithfulness” and a “happy sexual relationship,” on a list of nine things Americans associated with successful marriages. “I like hugs. I like kisses. But what I really love is help with the dishes,” summarized the Pew Research Center (2007).

Equity’s importance extends beyond marriage. Mutually sharing self and possessions, making decisions together, giving and getting emotional support, promoting and caring about each other’s welfare—all these acts are at the core of every type of loving relationship (Sternberg & Grajek, 1984). It’s true for lovers, for parent and child, and for close friends.

Another vital ingredient of loving relationships is self-disclosure, revealing intimate details about ourselves—our likes and dislikes, our dreams and worries, our proud and shameful moments. As one person reveals a little, the other returns the gift. The first then reveals more, and on and on, as friends or lovers move to deeper and deeper intimacy (Baumeister & Bratslavsky, 1999).

363

One study marched pairs of students through 45 minutes of increasingly self-disclosing conversation—from “When did you last sing to yourself” to “When did you last cry in front of another person? By yourself?” Others spent the time with small-talk questions, such as “What was your high school like?” (Aron et al., 1997). By the experiment’s end, those experiencing the escalating intimacy felt remarkably close to their conversation partner, much closer than did the small-talkers.

In the mathematics of love, self-disclosing intimacy + mutually supportive equality = enduring companionate love.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 12.16

How does the two-factor theory of emotion help explain passionate love?

Emotions consist of (1) physical arousal and (2) our interpretation of that arousal. Researchers have found that any source of arousal will be interpreted as passion in the presence of a desirable person.

Question 12.17

Two vital components for maintaining companionate love are __________ and __________-__________.

equity; self-disclosure

Altruism

12-15 What is altruism? When are we most—and least—likely to help?

Altruism is an unselfish concern for the welfare of others, such as Dirk Willems displayed when he rescued his jailer. Another heroic example of altruism took place in an underground New York City subway station. Construction worker Wesley Autrey and his 6- and 4-year-old daughters were waiting for their train when they saw a nearby man collapse in a convulsion. The man then got up, stumbled to the platform’s edge, and fell onto the tracks. With train headlights approaching, Autrey later recalled, “I had to make a split decision” (Buckley, 2007). His decision, as his girls looked on in horror, was to leap onto the track, push the man off the rails and into a foot-deep space between them, and lie on top of him. As the train screeched to a halt, five cars traveled just above his head, leaving grease on his knitted cap. When Autrey cried out, “I’ve got two daughters up there. Let them know their father is okay,” the onlookers erupted into applause.

Such selfless goodness made New Yorkers proud to call that city home. Another New York story, four decades earlier, had a different ending. In 1964, a stalker repeatedly stabbed Kitty Genovese, then raped her as she lay dying outside her Queens, New York, apartment at 3:30 A.M. “Oh, my God, he stabbed me!” Genovese screamed into the early morning stillness. “Please help me!” Windows opened and lights went on as neighbors heard her screams. Her attacker fled. Then he returned to stab and rape her again. Not until he had fled for good did anyone so much as call the police, at 3:50 A.M.

Bystander Intervention

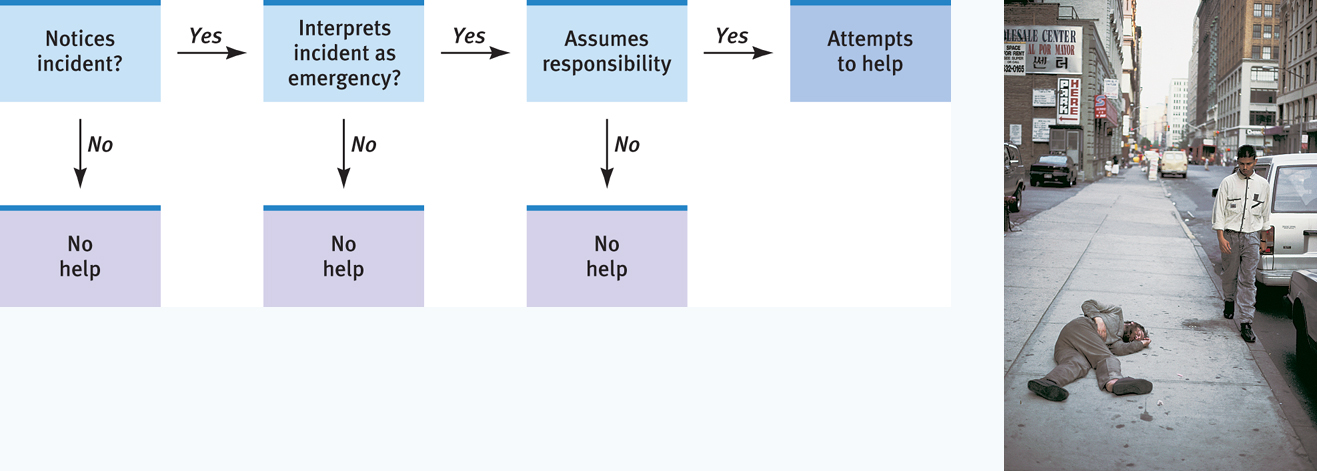

In an emergency, some people intervene, as Wesley Autrey did, but others, like the Genovese bystanders, fail to offer help. Why do some people become heroes in emergencies while others just stand and watch? Social psychologists John Darley and Bibb Latané (1968b) believed three conditions were necessary for bystanders to help (FIGURE 12.9). They

- notice the incident.

- interpret the event as an emergency.

- assume responsibility for helping.

364

At each step, the presence of others can turn people away from the path that leads to helping. Darley and Latané (1968a) reached these conclusions after interpreting the results of a series of experiments. For example, they staged a fake emergency in their laboratory as students participated in a discussion over an intercom. Each student was in a separate cubicle, and only the person whose microphone was switched on could be heard. When his turn came, one student (who was actually working for the experimenters) made sounds as though he were having an epileptic seizure, and he called for help.

How did the other students react? As FIGURE 12.10 shows, those who believed only they could hear the victim—and therefore thought they alone were responsible for helping him—usually went to his aid. Students who thought others also could hear the victim’s cries were more likely to react as Kitty Genovese’s neighbors had. When more people shared responsibility for helping—when no one person was clearly responsible—each listener was less likely to help.

Hundreds of additional experiments have confirmed this bystander effect. For example, researchers and their assistants took 1497 elevator rides in three cities and “accidentally” dropped coins or pencils in front of 4813 fellow passengers (Latané & Dabbs, 1975). When alone with the person in need, 40 percent helped; in the presence of five other bystanders, only 20 percent helped.

Observations of behavior in thousands of situations—relaying an emergency phone call, aiding a stranded motorist, donating blood, picking up dropped books, contributing money, giving time, and more—show that the best odds of our helping someone occur when

- the person appears to need and deserve help.

- the person is in some way similar to us.

- the person is a woman.

- we have just observed someone else being helpful.

- we are not in a hurry.

- we are in a small town or rural area.

- we are feeling guilty.

- we are focused on others and not preoccupied.

- we are in a good mood.

This last result, that happy people are helpful people, is one of the most consistent findings in all of psychology. As poet Robert Browning (1868) observed, “Oh, make us happy and you make us good!” It doesn’t matter how we are cheered. Whether by being made to feel successful and intelligent, by thinking happy thoughts, by finding money, or even by receiving a posthypnotic suggestion, we become more generous and more eager to help (Carlson et al., 1988).

So happiness breeds helpfulness. But it’s also true that helpfulness breeds happiness. Making charitable donations activates brain areas associated with reward (Harbaugh et al., 2007). That helps explain a curious finding: People who give money away are happier than those who spend it almost entirely on themselves. In one experiment, researchers gave people an envelope with cash and instructions either to spend it on themselves or to spend it on others (Dunn et al., 2008). Which group was happiest at the day’s end? It was, indeed, those assigned to the spend-it-on-others condition.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 12.18

Why didn’t anybody help Kitty Genovese? What social relations principle did this incident illustrate?

In the presence of others, an individual is less likely to notice a situation, correctly interpret it as an emergency, and then take responsibility for offering help. The Kitty Genovese case demonstrated this bystander effect, as each witness assumed many others were also aware of the event.

365

The Norms for Helping

12-16 How do social norms explain helping behavior?

Why do we help? Sometimes we go to the aid of another because we have been socialized to do so, through norms that prescribe how we ought to behave. Through socialization, we learn the reciprocity norm, the expectation that we should return help, not harm, to those who have helped us. In our relations with others of similar status, the reciprocity norm compels us to give (in favors, gifts, or social invitations) about as much as we receive.

The reciprocity norm kicked in after Dave Tally, a Tempe, Arizona, homeless man, found $3300 in a backpack that had been lost by an Arizona State University student headed to buy a used car (Lacey, 2010). Tally could have used the cash for much-needed bike repairs, food, and shelter. Instead, he turned the backpack in to the social service agency where he volunteered. To reciprocate Tally’s help, the student thanked him with a monetary reward. Hearing about Tally’s self-giving deeds, dozens of others also sent him money and job offers.

We also learn a social-responsibility norm : We should help those who depend on us. So we help young children and others who cannot give back as much as they receive. People who attend weekly religious services are often urged to practice the social-responsibility norm, and sometimes they do. Between 2006 and 2008, Gallup polls sampled more than 300,000 people across 140 countries, comparing those “highly religious” (who said religion was important to them and who had attended a religious service in the prior week) with those less religious. The highly religious, despite being poorer, were about 50 percent more likely to report having “donated money to a charity in the last month” and to have volunteered time to an organization (Pelham & Crabtree, 2008).

Although positive social norms encourage generosity and enable group living, conflicts often divide us.

Conflict and Peacemaking

12-17 What social processes fuel conflict? How can we transform feelings of prejudice and conflict into behaviors that promote peace?

We live in surprising times. With astonishing speed, recent democratic movements have swept away totalitarian rule in Eastern European and Arab countries. Yet every day, the world continues to spend more than $3 billion for arms and armies—money that could have been used for housing, nutrition, education, and health care. Knowing that wars begin in human minds, psychologists have wondered: What in the human mind causes destructive conflict? How might the perceived threats of our differences be replaced by a spirit of cooperation?

To a social psychologist, a conflict is the perception that actions, goals, or ideas are incompatible. The elements of conflict are much the same, whether we are speaking of nations at war, cultural groups feuding within a society, or partners sparring in a relationship. In each situation, people become tangled in a destructive process that can produce results no one wants.

Enemy Perceptions

Psychologists have noticed a curious tendency: People in conflict form evil images of one another. These distorted images are so similar that we call them mirror-image perceptions. As we see “them”—untrustworthy, with evil intentions—so “they” see us.

Mirror-image perceptions can feed a vicious cycle of hostility. If Juan believes Maria is annoyed with him, he may snub her. In return, she may act annoyed, justifying his perceptions. As with individuals, so with countries. Perceptions can become self-fulfilling prophecies.

We tend to see our own actions as responses to provocation, not as the causes of what happens next. Perceiving ourselves as returning tit for tat, we often hit back harder, as University College London volunteers did in one experiment (Shergill et al., 2003). After feeling pressure on their own finger, they were to use a mechanical device to press on another volunteer’s finger. Although told to reciprocate with the same amount of pressure, they typically responded with about 40 percent more force than they had just experienced. Despite seeking only to respond in kind, their touches soon escalated to hard presses, much as when each child after a fight claims that “I just poked him, but he hit me harder.”

The point is not that truth must lie midway between conflicting views (one may be more accurate). The point is that enemy perceptions often form mirror images. Moreover, as enemies change, so do perceptions. In American minds and media, the “bloodthirsty, cruel, treacherous” Japanese of World War II became “intelligent, hardworking, self-disciplined, resourceful allies” (Gallup, 1972).

Promoting Peace

How can we change perceptions and make peace? Can contact and cooperation transform the anger and fear fed by prejudice and conflicts into peaceful attitudes? Research indicates that, in some cases, they can.

366

“You cannot shake hands with a clenched fist.”

Indira Gandhi, 1971

CONTACT Does it help to put two conflicting parties into close contact? It depends. When contact is free of competition and between parties with equal status, such as fellow store clerks, it typically helps. Initially prejudiced co-workers of different races have, in such circumstances, usually come to accept one another. Across a quarter-million people studied in 38 nations, friendly contact with ethnic minorities, older people, and people with disabilities has usually led to less prejudice (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2011). Some examples:

- With interracial contact, South African Whites’ and Blacks’ “attitudes [have moved] into closer alignment” (Dixon et al., 2007; Finchilescu & Tredoux, 2010).

- Heterosexuals’ attitudes toward gay people are influenced not only by what they know but also by whom they know (Smith et al., 2009). In surveys, the reason people most often give for becoming more supportive of same-sex marriage is “having friends, family, or acquaintances who are gay or lesbian” (Pew, 2013).

- Even indirect contact with an outgroup member (via story reading or through a friend who has an outgroup friend) has reduced prejudice (Cameron & Rutland, 2006; Pettigrew et al., 2007).

However, contact is not always enough. In most desegregated schools, ethnic groups resegregate themselves in the lunchrooms and on the school grounds (Alexander & Tredoux, 2010; Clack et al., 2005; Schofield, 1986). People in each group often think they would welcome more contact with the other group, but they assume the other group does not share their interest (Richeson & Shelton, 2007). When these mirror-image untruths are corrected, friendships can form and prejudices melt.

COOPERATION To see if enemies could overcome their differences, researcher Muzafer Sherif (1966) manufactured a conflict. He separated 22 boys into two separate camp areas. Then he had the two groups compete for prizes in a series of activities. Before long, each group became intensely proud of itself and hostile to the other group’s “sneaky,” “smart-alecky stinkers.” Food wars broke out. Cabins were ransacked. Fistfights had to be broken up by camp counselors. Brought together, the two groups avoided each other, except to taunt and threaten. Little did they know that within a few days, they would be friends.

Sherif accomplished this reconciliation by giving them superordinate goals—shared goals that could be achieved only through cooperation. When he arranged for the camp water supply to “fail,” all 22 boys had to work together to restore water. To rent a movie in those pre-Netflix days, they all had to pool their resources. To move a stalled truck, all the boys had to combine their strength, pulling and pushing together. Sherif used shared predicaments and goals to turn enemies into friends. What reduced conflict was not mere contact, but cooperative contact.

A shared predicament likewise had a powerfully unifying effect in the weeks after the 9/11 terrorist attack. Patriotism soared as Americans felt “we” were under attack. Gallup-surveyed approval of “our President” shot up from 51 percent the week before the attack to a highest-ever 90 percent level just 10 days after (Newport, 2002). In chat groups and everyday speech, even the word we (relative to I) surged in the immediate aftermath (Pennebaker, 2002).

At such times, cooperation can lead people to define a new, inclusive group that dissolves their former subgroups (Dovidio & Gaertner, 1999). If this were a social psychology experiment, you might seat members of two groups not on opposite sides, but alternately around a table. Give them a new, shared name. Have them work together. Then watch “us” and “them” become “we.” After 9/11, one 18-year-old New Jersey man described this shift in his own social identity. “I just thought of myself as Black. But now I feel like I’m an American, more than ever” (Sengupta, 2001).

If superordinate goals and shared threats help bring rival groups together, might this principle bring people together in multicultural schools? Could interracial friendships replace competitive classroom situations with cooperative ones? Could cooperative learning maintain or even enhance student achievement? Experiments with teens from 11 countries confirm that, in each case, the answer is Yes (Roseth et al., 2008). In the classroom as in the sports arena, members of interracial groups who work together on projects typically come to feel friendly toward one another. Knowing this, thousands of teachers have made interracial cooperative learning part of their classroom experience.

367

The power of cooperative activity to make friends of former enemies has led psychologists to urge increased international exchange and cooperation. Let us engage in mutually beneficial trade, working together to protect our common destiny on this fragile planet and becoming more aware that our hopes and fears are shared. By taking such steps, we can change misperceptions that drive us apart and instead join together in a common cause based on common interests. As working toward shared goals reminds us, we are more alike than different.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 12.19

Why do sports fans tend to feel a sense of satisfaction when their archrival team loses? Why do such feelings, in other settings, make conflict resolution more challenging?

Sports fans may feel a part of an ingroup that sets itself apart from an outgroup (fans of the archrival team). Ingroup bias tends to develop, leading to prejudice and the view that the outgroup “deserves” misfortune. So, the archrival team’s loss may seem justified. In conflicts, this kind of thinking is problematic, especially when each side in the conflict develops mirror-image perceptions of the other (distorted, negative images that are ironically similar).

Question 12.20

What are two ways to reconcile conflicts and promote peace?

Peacemakers should encourage equal-status contact and cooperation to achieve superordinate goals (shared goals that override differences).