What Is a Psychological Disorder?

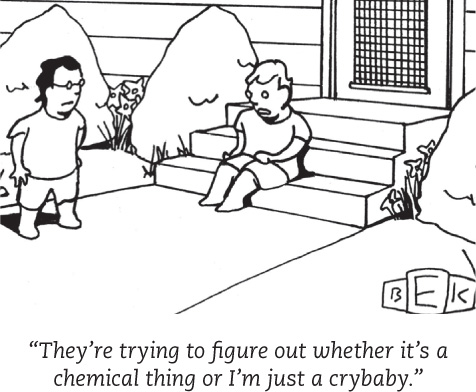

Most of us would agree that a family member who is depressed and refuses to get out of bed for three months has a psychological disorder. But what should we say about a grieving father who can’t resume his usual social activities three months after his child has died? Where do we draw the line between clinical depression and understandable grief? Between bizarre irrationality and zany creativity? Between abnormality and normality?

Most of us would agree that a family member who is depressed and refuses to get out of bed for three months has a psychological disorder. But what should we say about a grieving father who can’t resume his usual social activities three months after his child has died? Where do we draw the line between clinical depression and understandable grief? Between bizarre irrationality and zany creativity? Between abnormality and normality?

In their search for answers, theorists and clinicians consider several perspectives:

- How should we define psychological disorders?

- How should we understand disorders? How do underlying biological factors contribute to disorder? How do troubling environments influence our well-being? And how do these effects of nature and nurture interact?

- How should we classify psychological disorders? How can we use labels to guide treatment without stigmatizing people or excusing their behavior?

Defining Psychological Disorders

13-1 How should we draw the line between normal behavior and psychological disorder?

A psychological disorder is a syndrome marked by a “clinically significant disturbance in an individual’s cognitions, emotion regulation, or behavior” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

A psychological disorder is a syndrome marked by a “clinically significant disturbance in an individual’s cognitions, emotion regulation, or behavior” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Disturbed, or dysfunctional, thoughts, emotions, or behaviors interfere with normal day-to-day life—they are maladaptive. An intense fear of spiders may be abnormal, but if it doesn’t interfere with your life, it is not a disorder. Believing that your home must be thoroughly cleaned every weekend is not a disorder. But when cleaning rituals interfere with work and leisure, as Marc’s did in this chapter’s opening, they may be signs of a disorder. And occasional sad moods that persist and become disabling may likewise signal a psychological disorder.

People are often distressed by their dysfunctional thoughts, emotions, or behaviors. Marc, Greta, and Stuart all experienced distress about their behaviors or emotions.

The diagnosis of specific disorders has varied from culture to culture and even over time in the same culture. By 1973, mental health workers no longer considered same-sex attraction as inherently dysfunctional or distressing. The American Psychiatric Association therefore dropped homosexuality from its list of disorders. On the other hand, high-energy children, who might have been viewed as normal youngsters running a bit wild in the 1970s, may today receive a diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). (See Thinking Critically About: ADHD—Normal High Energy or Disordered Behavior?) Times change, and research and clinical practices change, too.

Understanding Psychological Disorders

13-3 How is our understanding of psychological disorders affected by whether we use a medical model or a biopsychosocial approach?

The way we view a problem influences how we try to solve it. In earlier times, people often thought that strange behaviors were evidence that strange forces were at work. Had you lived during the Middle Ages, you might have said, “The devil made him do it.” To drive out demons, “mad” people were sometimes caged or given “therapies” such as beatings, genital mutilations, removal of teeth or lengths of intestine, or transfusions of animal blood (Farina, 1982).

The way we view a problem influences how we try to solve it. In earlier times, people often thought that strange behaviors were evidence that strange forces were at work. Had you lived during the Middle Ages, you might have said, “The devil made him do it.” To drive out demons, “mad” people were sometimes caged or given “therapies” such as beatings, genital mutilations, removal of teeth or lengths of intestine, or transfusions of animal blood (Farina, 1982).

Reformers such as Philippe Pinel (1745–1826) in France opposed such brutal treatments. Madness is not demon possession, he insisted, but a sickness of the mind caused by severe stress and inhumane conditions. Curing the sickness requires “moral treatment,” including boosting patients’ morale by unchaining them and talking with them. He and others worked to replace brutality with gentleness, isolation with activity, and filth with clean air and sunshine.

373

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT

ADHD—Normal High Energy or Disordered Behavior?

13-2 Why is there controversy over attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder?

Eight-year-old Todd has always been full of energy. At home, he chatters away and darts from one activity to the next. He rarely settles down to read a book or focus on a game. At play, he is reckless. He overreacts when playmates bump into him or take one of his toys. At school, he fidgets, and his teacher complains that he doesn’t listen, follow instructions, or stay in his seat and do his lessons.

If taken for a psychological evaluation, Todd may be diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Some 11 percent of American 4- to 17-year-olds receive this diagnosis after displaying its key symptoms (extreme inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity) (Schwarz & Cohen, 2013). Studies also find that 2.5 percent of adults—though the number grows smaller with age—have ADHD symptoms (Simon et al., 2009). (Psychiatry’s new diagnostic manual has loosened the criteria for adult ADHD, leading critics to fear increased diagnosis and overuse of prescription drugs [Frances, 2012].)

To skeptics, being distractible, fidgety, and impulsive sounds like a “disorder” caused by a single genetic variation: a Y chromosome (the male sex chromosome). And sure enough, ADHD is diagnosed more than twice as often in boys as in girls. Does energetic child + boring school = ADHD overdiagnosis?

Skeptics think so. Depending on where they live, children who are “a persistent pain in the neck in school” are often diagnosed with ADHD and given powerful prescription drugs (Gray, 2010). But the problem may reside less in the child than in today’s abnormal environment that forces children to do what evolution has not prepared them to do—to sit for long hours in chairs. In more natural outdoor environments, these healthy schoolchildren might seem perfectly normal.

Rates of medication for presumed ADHD vary by age, sex, and location. Prescription drugs are more often given to teens than to younger children. Boys are nearly three times more likely to receive them than are girls. And location matters. Among 4- to 17-year-olds, prescription rates have varied from 1 percent in Nevada to 9 percent in North Carolina (CDC, 2013). Some students seek out the stimulant drugs—calling them the “good-grade pills.” They hope to increase their focus and achievement, but the risk is eventual addiction and mood disorder (Schwarz, 2012).

Not everyone agrees that ADHD is being overdiagnosed. Some argue that today’s more frequent diagnoses reflect increased awareness of the disorder, especially in those areas where rates are highest. They also note that diagnoses can be inconsistent—ADHD is not as clearly defined as, for example, a broken arm is. Nevertheless, declared the World Federation for Mental Health (2005), “there is strong agreement among the international scientific community that ADHD is a real neurobiological disorder whose existence should no longer be debated.” A consensus statement by 75 researchers noted that in neuroimaging studies, ADHD has associations with abnormal brain activity patterns (Barkley et al., 2002).

What, then, is known about ADHD’s causes? It is not caused by too much sugar or poor schools. ADHD often coexists with a learning disorder or with defiant and temper-prone behavior. ADHD is heritable, and research teams are sleuthing the culprit gene variations and abnormal neural pathways (Nikolas & Burt, 2010; Poelmans et al., 2011; Volkow et al., 2009; Williams et al., 2010). It is treatable with medications such as Ritalin and Adderall, which are considered stimulants but help calm hyperactivity and increase one’s ability to sit and focus on a task—and to progress normally in school (Barbaresi et al., 2007). Psychological therapies, such as those focused on shaping behaviors in the classroom and at home, have also helped address the distress of ADHD (Fabiano et al., 2008).

The bottom line: Extreme inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity can derail social, academic, and vocational achievements, and these symptoms can be treated with medication and other therapies. But the debate continues over whether normal high energy is too often diagnosed as a psychiatric disorder, and whether there is a cost to the long-term use of stimulant drugs in treating ADHD.

The Medical Model

By the 1800s, a medical breakthrough prompted further reform. Researchers discovered that syphilis, a sexually transmitted infection, invades the brain and distorts the mind. This discovery triggered an excited search for physical causes of other mental disorders, and for treatments that would cure them. Hospitals replaced madhouses, and the medical model of mental disorders was born. This model is reflected in words we still use today. We speak of the mental health movement. A mental illness needs to be diagnosed on the basis of its symptoms. It needs to be cured through therapy, which may include treatment in a psychiatric hospital. Recent discoveries that abnormal brain structures and biochemistry contribute to some disorders have energized the medical perspective.

374

The Biopsychosocial Approach

To call psychological disorders “sicknesses” tilts research heavily toward the influence of biology and away from the influence of our personal histories and social and cultural surroundings. But as we have seen throughout this text, our behaviors, our thoughts, and our feelings are formed by the interaction of our biology, our psychology, and our social-cultural environment. As individuals, we differ in the amount of stress we experience and in the ways we cope with stress. Cultures also differ in the ways people experience and cope with stress.

The environment’s influence on disorders can be seen in culture-related symptoms (Beardsley, 1994; Castillo, 1997). Anxiety, for example, may be exhibited in different ways in different cultures. In Latin American cultures, people may suffer from susto, a condition marked by severe anxiety, restlessness, and a fear of black magic. In Japanese culture, people may experience taijin-kyofusho—social anxiety about their appearance, combined with a readiness to blush and a fear of eye contact. The eating disorder bulimia nervosa occurs mostly in food-abundant Western cultures. Increasingly, however, North American disorders, along with McDonalds and MTV, have spread the globe (Watters, 2010).

Other disorders, such as depression and schizophrenia, have appeared more consistently worldwide. From Asia to Africa and across the Americas, people with schizophrenia often act irrationally and speak in disorganized ways. Such disorders reflect genes and physiology, as well as psychological dynamics and cultural circumstances. The biopsychosocial approach reminds us that mind and body are inseparable. We are mind embodied.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 13.1

Are psychological disorders culture-specific? Explain with examples.

Some psychological disorders are culture-specific. For example, bulimia nervosa occurs mostly in food-rich Western cultures, and taijin-kyofusho appears largely in Japan. Other disorders, such as schizophrenia, appear across cultures.

Question 13.2

What is the biopsychosocial perspective, and why is it important in our understanding of psychological disorders?

Biological, psychological, and social-cultural influences combine to produce psychological disorders. This broad perspective stresses that our well-being is affected by the interaction of many forces: our genes, brain functioning, inner thoughts and feelings, and the influences of our social and cultural environment.

Classifying Disorders—and Labeling People

13-4 How and why do clinicians classify psychological disorders, and why do some psychologists criticize the use of diagnostic labels?

In biology, classification creates order and helps us communicate. To say that an animal is a “mammal” tells us a great deal—that it is warm-blooded, has hair or fur, and produces milk to feed its young. In psychiatry and psychology, classification also tells us a great deal. To classify a disorder as “schizophrenia” implies that the person speaks in a disorganized way, has bizarre beliefs, shows either little emotion or inappropriate emotion, or is socially withdrawn. “Schizophrenia” is a quick way of describing a complex set of behaviors.

But diagnostic classification does more than give us a thumbnail sketch of a person’s disordered behavior. In psychiatry and psychology, classification also attempts to predict the disorder’s future course and to suggest treatment. And it prompts research into causes. To study a disorder we must first name and describe it.

The most common tool for describing disorders and estimating how often they occur is the American Psychiatric Association’s 2013 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, now in its fifth edition (DSM-5 ). (Many examples in this chapter were drawn from the case studies in a previous DSM edition.) Physicians and mental health workers use the detailed “diagnostic criteria and codes” in the DSM-5 to guide medical diagnoses and define who is eligible for treatments, including medication (and corresponding insurance coverage). For example, a person may be diagnosed with and treated for “insomnia disorder” if he or she meets all of the following criteria:

- Is dissatisfied with sleep quantity or quality (difficulty initiating, maintaining, or returning to sleep)

- Sleep disturbance causes distress or impairment in everyday functioning

- Occurs at least three nights per week

- Present for at least three months

- Occurs despite adequate opportunity for sleep

- Is not explained by another sleep disorder (such as narcolepsy)

- Is not caused by substance use or abuse

- Is not caused by other mental disorders or medical conditions

In this new edition, some diagnostic labels have changed. As noted in Chapter 3, the conditions formerly called “autism” and “Asperger’s syndrome” have now been combined under the label autism spectrum disorder. “Mental retardation” has become intellectual disability. New categories include hoarding disorder, and binge-eating disorder.

Some new or altered diagnoses are controversial. Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder is a new DSM-5 diagnosis for children “who exhibit persistent irritability and frequent episodes of behavior outbursts three or more times a week for more than a year.” Will this diagnosis assist parents who struggle with unstable children, or will it “turn temper tantrums into a mental disorder” and lead to overmedication, as the chair of the previous DSM edition has warned (Frances, 2012)? Another change that has triggered some debate is that prolonged bereavement can now be diagnosed as depression. Patients with this diagnosis are now eligible for insurance coverage for antidepressant drugs. Companies that market those drugs will benefit. Some protest that depression after a loved one’s death should not be considered abnormal; others argue that depression is depression, regardless of its trigger.

375

Real-world tests (field trials) have assessed clinician agreement when using the new DSM-5 categories (Freedman et al., 2013). Some diagnoses, such as adult posttraumatic stress disorder and childhood autism spectrum disorder, fared well—with agreement near 70 percent. (If one psychiatrist or psychologist diagnosed someone with autism spectrum disorder, there was a 70 percent chance that another mental health worker would independently give the same diagnosis.) Others, such as antisocial personality disorder and generalized anxiety disorder, fared poorly.

Critics have long faulted the DSM manual for casting too wide a net and bringing “almost any kind of behavior within the compass of psychiatry” (Eysenck et al., 1983). They worry that the DSM-5 will extend the pathologizing of everyday life—for example, by turning bereavement grief into depression and boyish rambunctiousness into ADHD (Frances, 2013). Others respond that depression and hyperactivity, though needing careful definition, are genuine disorders—even, for example, those triggered by a major life stress such as a death when the grief does not go away (Kendler, 2011; Kupfer, 2012).

Other critics have registered a more basic complaint—that these labels are just society’s value judgments (Farina, 1982). Labels can change reality by putting us on the alert for evidence that confirms our view. When teachers are told certain students are “gifted,” they may act in ways that bring out the creative behavior they expect (Snyder, 1984). If we hear that a new co-worker is a difficult person, we may treat the person suspiciously. He or she may in turn respond to us as a difficult person would. Labels can be self-fulfilling.

The biasing power of labels was clear in a now-classic study. David Rosenhan (1973) and seven others went to hospital admissions offices, complaining (falsely) of “hearing voices” saying empty, hollow, and thud. Apart from this complaint and giving false names and occupations, they answered questions truthfully. All eight of these normal people were misdiagnosed with disorders.

Should we be surprised? As one psychiatrist noted, if someone swallows blood, goes to an emergency room, and spits it up, should we blame the doctor for diagnosing a bleeding ulcer? Surely not. But what followed the diagnosis in the Rosenhan study was startling. Until being released an average of 19 days later, these eight “patients” showed no other symptoms. Yet after analyzing their (quite normal) life histories, clinicians were able to “discover” the causes of their disorders, such as having mixed emotions about a parent. Even routine note-taking behavior was misinterpreted as a symptom.

The power of labels is just as real outside the laboratory. Getting a job or finding a place to rent can be a challenge for people recently released from a mental hospital. Label someone as “mentally ill” and people may fear them as potentially violent (see Close-Up: Are People With Psychological Disorders Dangerous?). That reaction seems to be fading as people better understand that many psychological disorders are diseases of the brain, not failures of character (Solomon, 1996). Public figures have helped foster this new understanding by speaking openly about their own struggles with disorders such as depression.

When people in another experiment watched videotaped interviews, those told that they were watching job applicants perceived the people as normal (Langer et al., 1974, 1980). Others, who were told they were watching psychiatric or cancer patients, perceived them as “different from most people.” Labels matter. One therapist who thought he was watching an interview of a psychiatric patient described the person as “frightened of his own aggressive impulses,” a “passive, dependent type,” and so forth. As Rosenhan discovered, a label can have “a life and an influence of its own.”

Despite their risks, diagnostic labels have benefits. They help mental health professionals communicate about their cases, pinpoint underlying causes, and share information about effective treatments. They are useful in research that explores the causes and treatments of disorders. And clients are often glad that the nature of their suffering has a name, and that they are not alone in experiencing this collection of symptoms.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 13.3

What is the value, and what are the dangers, of labeling individuals with disorders?

Therapists and others use disorder labels to communicate with one another in a common language. Clients may benefit from knowing they are not the only ones with these symptoms. Insurance companies require a diagnosis (a label) before they will pay for therapy. The danger of labeling people is that they will begin to act as they have been labeled, and also that labels can trigger assumptions that will change our behavior toward the people we label.

376

C L O S E - U P

Are People With Psychological Disorders Dangerous?

Movies and television sometimes portray people with psychological disorders as homicidal. Mass killings in 2012 by apparently disturbed people in a Colorado theater and a Connecticut elementary school reinforced public perceptions that people with psychological disorders are dangerous (Jorm et al., 2012). Thus, “People who have mental issues should not have guns,” said New York’s governor (Kaplan & Hakim, 2013).

Do disorders actually increase risk of violence, and can clinicians predict who is likely to do harm? In real life, the vast majority of violent crimes are committed by those with no diagnosed disorder (Fazel & Grann, 2006). Moreover, mental disorders seldom lead to violence, and clinical prediction of violence is unreliable.

The few people with disorders who do commit violent acts tend to be either those who experience threatening delusions and hallucinated voices that command them to act, or those who abuse substances (Douglas et al., 2009; Elbogen & Johnson, 2009; Fazel et al., 2009, 2010). People with disorders also are more likely to be victims than perpetrators of violence (Marley & Bulia, 2001). Indeed, reported the U.S. Surgeon General’s Office (1999, p. 7), “There is very little risk of violence or harm to a stranger from casual contact with an individual who has a mental disorder.” People with mental illness commit proportionately little gun violence. Thus, focusing gun restrictions only on mentally ill people is unlikely to significantly reduce gun violence (Friedman, 2012).

Better predictors of violence are use of alcohol or drugs, previous violence, and gun availability. The mass-killing shooters had one more thing in common: They were young males. “We could avoid two-thirds of all crime simply by putting all able-bodied young men in a cryogenic sleep from the age of 12 through 28,” said one psychologist (Lykken, 1995).