Mood Disorders

13-14 What are the main mood disorders?

Many of us have had close encounters with the emotional extremes of mood disorders, which appear in two principal forms:

Many of us have had close encounters with the emotional extremes of mood disorders, which appear in two principal forms:

- Major depressive disorder is a persistent state of hopeless depression.

- Bipolar disorder is an alternation between depression and overexcited hyperactivity.

In the past year, have you at some time “felt so depressed that it was difficult to function”? If so, you were not alone. In one national survey, 31 percent of American collegians answered Yes (ACHA, 2009). The college years are an exciting time, but they can also be stressful. Perhaps you wanted to go to college right out of high school but couldn’t afford it, and now you are struggling to find time for school amid family and work responsibilities. Perhaps social stresses, such as a relationship gone sour or your feeling excluded, have made you feel isolated or plunged you into despair. Dwelling on these thoughts may have you down about your life or your future. You may lack the energy to get things done or even to force yourself out of bed. You may be unable to concentrate, eat, or sleep normally. Occasionally, you may even wonder if you would be better off dead.

To feel bad in reaction to very sad events is to be in touch with reality. In such times, depression is like a car’s oil light—a signal that warns us to stop and take appropriate measures. Depression makes sense from an evolutionary perspective. As one social psychologist warned, “If someone offered you a pill that would make you permanently happy, you would be well advised to run fast and run far. Emotion is a compass that tells us what to do, and a compass that is perpetually stuck on NORTH is worthless” (Gilbert, 2006). Biologically speaking, life’s purpose is survival and reproduction, not happiness. Just as coughing, vomiting, and various forms of pain protect our body from dangerous toxins, so depression protects us from dangerous thoughts and feelings. It slows us down and gives us time to think hard and consider our options (Wrosch & Miller, 2009). It defuses aggression, cuts back on risk taking, and focuses our mind (Allen & Badcock, 2003; Andrews & Thomson, 2009).

After reassessing our life, we may redirect our energy in more promising ways. Even mild sadness can make people more discerning, and help them make complex decisions (Forgas, 2009). It can also help them process and recall faces more accurately (Hills et al., 2011). There is sense to suffering.

Sometimes, however, depression becomes seriously maladaptive. How do we recognize the difference between a normal blue mood and abnormal depression?

Major Depressive Disorder

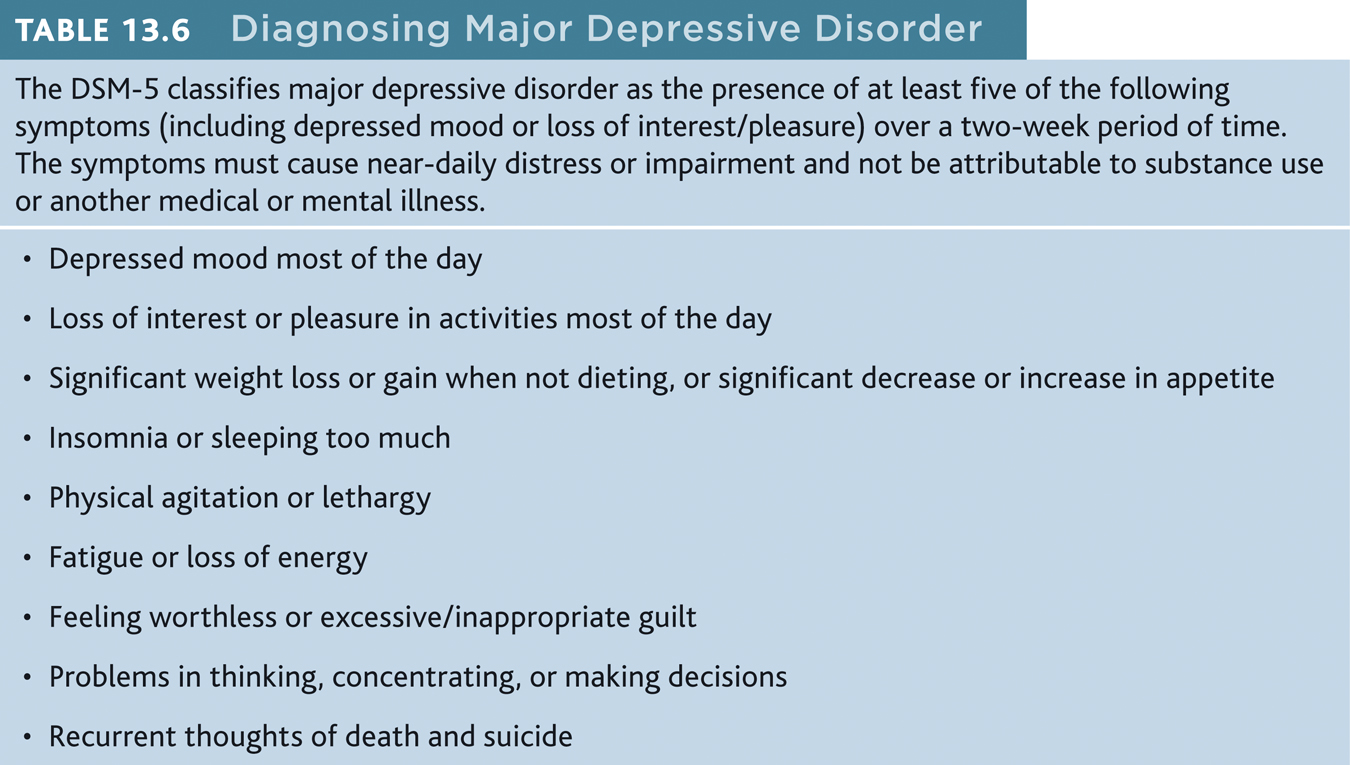

Joy, contentment, sadness, and despair are different points on a continuum, points at which any of us may be found at any given moment. The difference between a blue mood after bad news and major depressive disorder is like the difference between gasping for breath after a hard run and having chronic asthma. Major depressive disorder occurs when signs of depression last two or more weeks and are not caused by drugs or a medical condition. These signs include lethargy (extreme lack of energy), feelings of worthlessness, or loss of interest in family, friends, and activities (TABLE 13.6). To sense what major depression feels like, imagine combining the anguish of grief with the exhaustion you feel after pulling an all-nighter.

Although phobias are more common, depression is the number one reason people seek mental health services. Worldwide, it is the leading cause of disability—afflicting at least 350 million people (WHO, 2012). With or without therapy, most of these people will temporarily or permanently return to their previous nondepressed state.

391

Adults diagnosed with persistent depressive disorder (also called dysthymia) experience a mildly depressed mood more often than not for at least two years (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). They also display at least two of depression’s symptoms.

Bipolar Disorder

In bipolar disorder, people bounce from one emotional extreme to the other (week to week, and not day to day or moment to moment). When a depressive episode ends, an intensely happy, overly talkative, wildly energetic, and extremely optimistic state called mania follows. But before long, the elated mood either returns to normal or plunges again into depression.

The Granger Collection

Jemal Countess/Getty Images

If depression is living in slow motion, mania is fast forward. During mania, people feel little need for sleep, are easily irritated, and show fewer sexual inhibitions. Feeling extreme optimism and self-esteem, they find advice annoying. Yet they need protection from their poor judgment, which may lead to reckless spending or unsafe sex.

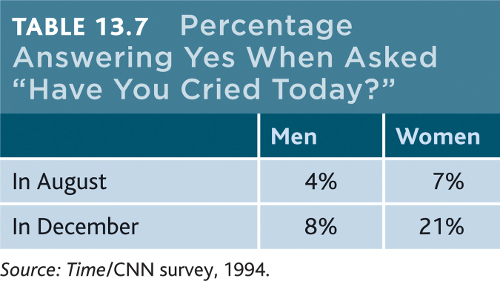

For some people suffering depressive disorders or bipolar disorder, symptoms may have a seasonal pattern. Depression may regularly return each fall or winter, and mania (or a reprieve from depression) may dependably arrive with spring. For many others, winter darkness simply means more blue moods. When asked “Have you cried today?” Americans have agreed more often in the winter (TABLE 13.7).

In milder forms, mania’s energy and flood of ideas can fuel creativity. Classical composer George Frideric Handel (1685–1759), who many believe suffered a mild form of bipolar disorder, composed his nearly four-hour-long Messiah during three weeks of intense, creative energy (Keynes, 1980). Bipolar disorder strikes more often among people who rely on emotional expression and vivid imagery, such as poets and artists, and less often among those who rely on precision and logic, such as architects, designers, and journalists (Jamison, 1993, 1995; Kaufman & Baer, 2002; Ludwig, 1995).

392

Bipolar disorder is as maladaptive as major depressive disorder, but it is much less common. It afflicts as many men as women. The diagnosis has risen among adolescents, whose mood swings, sometimes prolonged, range from rage to giddiness. The trend was clear in U.S. National Center for Health Statistics annual physician surveys. Between 1994 and 2003, bipolar diagnoses in under-20 people showed an astonishing 40-fold increase—from an estimated 20,000 to 800,000 (Carey, 2007; Flora & Bobby, 2008; Moreno et al., 2007). The new popularity of the diagnosis has been a boon to companies whose drugs are prescribed to lessen the mood swings. The DSM-5 will likely reduce the number of child and adolescent bipolar diagnoses, by classifying as disruptive mood dysregulation disorder some of those with emotional volatility (Miller, 2010).

This surge in diagnoses has prompted debate over whether normal mood swings are sometimes being labeled abnormal and then medicated.

Suicide and Self-Injury

13-15 Why do people attempt suicide, and why do some people injure themselves?

Each year nearly 1 million despairing people worldwide will elect a permanent solution to what might have been a temporary problem (WHO, 2012). The risk of suicide is at least five times greater for those who have been depressed than for the general population (Bostwick & Pankratz, 2000). People seldom, however, elect suicide while in the depths of depression, when energy and initiative are lacking. The risk increases when they begin to rebound and become capable of following through.

Suicide is not necessarily an act of hostility or revenge. Elderly people sometimes choose death as an alternative to current or future suffering. People of all ages may view suicide as a way of switching off unendurable pain and relieving a perceived burden on family members. “People desire death when two fundamental needs are frustrated to the point of extinction,” noted one psychologist: “The need to belong with or connect to others, and the need to feel effective with or to influence others” (Joiner, 2006, p. 47). Suicidal urges typically increase when people feel disconnected from others and a burden to them (Joiner, 2010), or when they feel defeated and trapped by a situation they feel they cannot escape (Taylor et al., 2011). Thus, suicide rates increase a bit during economic recessions (Luo et al., 2011).

Looking back, families and friends may recall signs that they believe should have forewarned them—verbal hints, giving possessions away, self-inflicted injuries, or withdrawal and preoccupation with death. But few who talk or think of suicide (a number that includes one-third of all adolescents and college students) actually attempt it. Only about 1 in 25 Americans who make the attempt will complete the act (AAS, 2009). Nevertheless, about 30,000 will kill themselves—about two-thirds using guns. (Drug overdoses account for about 80 percent of suicide attempts, but only 14 percent of suicide fatalities.) States with high gun ownership are states with high suicide rates, even after controlling for poverty and urbanization (Miller et al., 2002; Tavernise, 2013).

Suicide is not the only way to send a message or deal with distress. Some people, especially some adolescents and young adults, may engage in nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI). Such behavior includes cutting or burning the skin, hitting oneself, pulling out hair, inserting objects under the nails or skin, and self-administered tattooing (Fikke et al., 2011).

Why do people hurt themselves? Those who do so tend to be less able to tolerate emotional distress. They are often extremely self-critical, with poor communication and problem-solving skills (Nock, 2010). They may engage in NSSI to

- gain relief from intense negative thoughts through the distraction of pain.

- ask for help and gain attention.

- relieve guilt by self-punishment.

- get others to change their negative behavior (bullying, criticism).

- fit in with a peer group.

Does NSSI lead to suicide? Usually not. Those who engage in NSSI are typically “suicide gesturers,” not suicide attempters (Nock & Kessler, 2006). Suicide gesturers engage in NSSI as a desperate but non-life-threatening form of communication or when they are feeling overwhelmed. But NSSI is a risk factor for future suicide attempts (Wilkinson & Goodyer, 2011). If people do not find help, their nonsuicidal behavior may escalate to suicidal thoughts and, finally, to suicide attempts.

393

The point to remember: If a friend talks suicide to you or engages in NSSI, it’s important to listen and to direct the person to professional help. Your friend may at least be sending a signal of feeling desperate or beyond hope.

Understanding Mood Disorders

13-16 How do mood disorders develop? What roles do biology, thinking, and social behavior play?

From thousands of studies of the causes, treatment, and prevention of mood disorders, researchers have pulled out some common threads. Here are some findings that any theory of depression must explain (Lewinsohn et al., 1985, 1998, 2003).

BEHAVIORS AND THOUGHTS CHANGE WITH DEPRESSION. People trapped in a depressed mood are inactive and feel unmotivated. They are sensitive to negative happenings (Peckham et al., 2010). They recall negative information. And they expect negative outcomes (my team will lose, my grades will fall, my love will fail). When the mood lifts, these behaviors and thoughts disappear. Nearly half the time, people with depression also have symptoms of another disorder, such as anxiety or substance use disorder.

DEPRESSION IS WIDESPREAD. Depression is found worldwide. (So, also, is schizophrenia.) This suggests that depression’s causes, too, must be common.

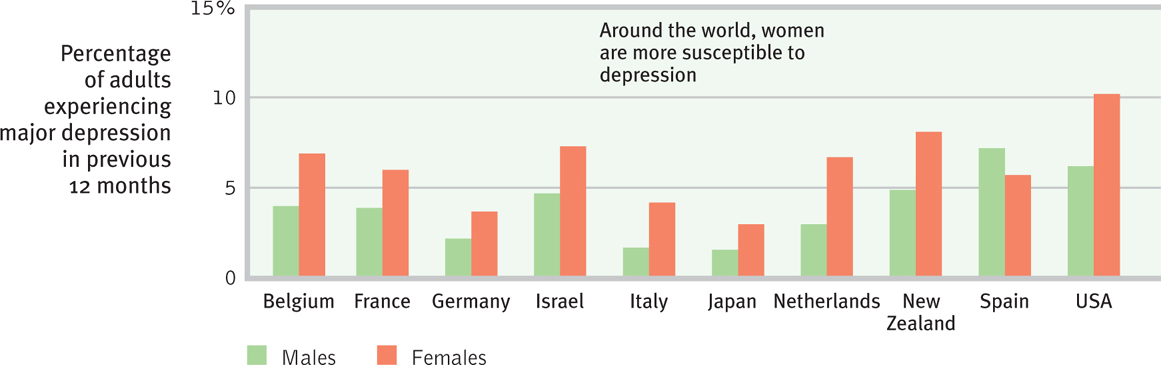

WOMEN’S RISK OF MAJOR DEPRESSION IS NEARLY DOUBLE MEN’S. In 2009, when Gallup pollsters asked more than a quarter-million Americans if they had ever been diagnosed with depression, 13 percent of men and 22 percent of women said Yes (Pelham, 2009). When Gallup asked Americans if they experienced sadness “during a lot of the day yesterday,” 17 percent of men and 28 percent of women answered Yes (Mendes & McGeeney, 2012). This gender gap has been found worldwide (FIGURE 13.8). The trend begins in adolescence; preadolescent girls are not more depression-prone than boys are (Hyde et al., 2008).

The depression gender gap fits a bigger pattern. Women are generally more vulnerable to disorders involving internal states, such as depression, anxiety, and inhibited sexual desire. Men’s disorders tend to be more external—alcohol use disorder, antisocial conduct, lack of impulse control. When women get sad, they often get sadder than men do. When men get mad, they often get madder than women do.

MOST MAJOR DEPRESSIVE EPISODES END ON THEIR OWN. Although therapy often speeds recovery, most people suffering major depression eventually return to normal even without professional help. The black cloud of depression comes and, a few weeks or months later, it often goes. About half the time, it recurs within two years (Burcusa & Iacono, 2007). Recovery is more likely to endure (Fergusson & Woodward, 2002; Kendler et al., 2001; Richards, 2011) when

- the first episode strikes later in life.

- there were few previous episodes.

- the person experiences minimal stress.

- there is ample social support.

STRESSFUL EVENTS SOMETIMES PRECEDE DEPRESSION. A family member’s death, a job loss, a marital crisis, or a physical assault increase one’s risk of depression. One long-term study tracked rates of depression in 2000 people (Kendler, 1998). Among those who had experienced no stressful life event in the preceding month, the risk of depression was less than 1 percent. Among those who had experienced three such events in that month, the risk was 24 percent. Surveys before and after Hurricane Sandy in 2012 revealed a 25 percent increase in clinical depression rates in the most affected areas (Witters & Ander, 2013).

WITH EACH NEW GENERATION, DEPRESSION IS STRIKING EARLIER IN LIFE (NOW OFTEN IN THE LATE TEENS) AND AFFECTING MORE PEOPLE. This has been true in Canada, England, France, Germany, Italy, Lebanon, New Zealand, Puerto Rico, Taiwan, and the United States (Collishaw et al., 2007; Cross-National Collaborative Group, 1992; Kessler et al., 2010; Twenge et al., 2008). In North America, today’s young adults are three times more likely than their grandparents to report having recently—or ever—suffered depression. This is true even though their grandparents have been at risk for many more years.

The increased risk among young adults appears partly real, but it may also reflect increased reporting due to cultural differences. Today’s young people are more willing to talk openly about their depression. Psychological processes may help explain the generational differences in reporting of depression. We tend to forget many negative experiences over time, so older generations may overlook depressed feelings they had in earlier years.

Biological Influences

Depression is a whole-body disorder that may disrupt sleep, appetite, energy, and concentration. It involves genetic predispositions and biochemical imbalances as well as negative thoughts and a gloomy mood.

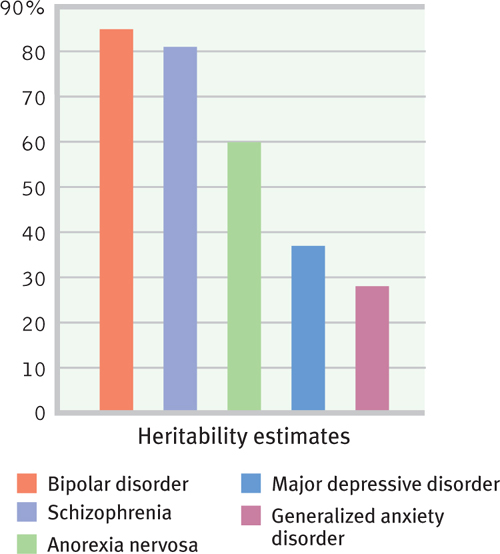

GENES AND DEPRESSION We have long known that mood disorders run in families. The risk of major depression and bipolar disorder increases if you have a parent or sibling with the disorder (Sullivan et al., 2000). If one identical twin is diagnosed with major depressive disorder, the chances are about 1 in 2 that at some time the other twin will be, too. If one identical twin has bipolar disorder, the chances are 7 in 10 that the other twin will at some point be diagnosed similarly. Among fraternal twins, the corresponding odds are just under 2 in 10 (Tsuang & Faraone, 1990). The greater similarity among identical twins holds even among twins raised apart (DiLalla et al., 1996). Summarizing the major twin studies (see FIGURE 13.9 ), one research team estimated the heritability of major depression (the extent to which individual differences are attributable to genes) at 37 percent (Bienvenu et al., 2011).

To tease out the genes that put people at risk for depression, some researchers have turned to linkage analysis. After finding families in which the disorder appears across several generations, geneticists examine DNA from affected and unaffected family members, looking for differences. Linkage analysis points us to a chromosome neighborhood, note behavior genetics researchers; “a house-to-house search is then needed to find the culprit gene” (Plomin & McGuffin, 2003). Such studies are reinforcing the view that depression is a complex condition. Many genes work together, producing a mosaic of small effects that interact with other factors to put some people at greater risk. If the culprit gene variations can be identified—with chromosome 3 genes implicated in separate British and American studies (Breen et al., 2011; Pergadia et al., 2011)—they may open the door to more effective drug therapy.

395

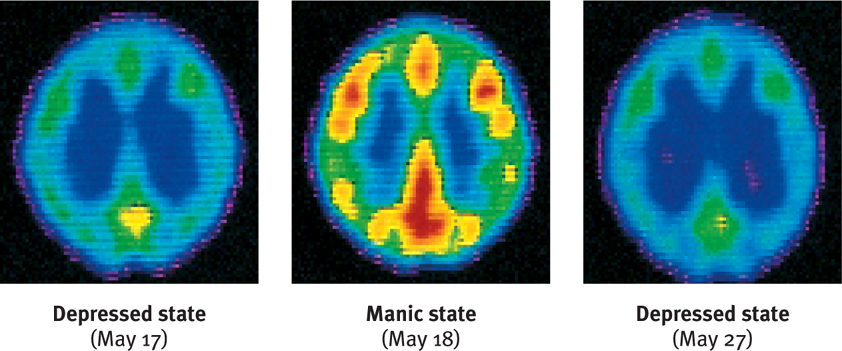

THE DEPRESSED BRAIN Scanning devices open a window on the brain’s activity during depressed and manic states. During depression, brain activity slows. During mania, it increases (FIGURE 13.10). The left frontal lobe, which is active during positive emotions, is less active during depressed times (Davidson et al., 2002).

At least two neurotransmitter systems are at work during these periods of activity and inactivity. Norepinephrine increases arousal and boosts mood. It is scarce during depression and overabundant during mania. Serotonin is also scarce or inactive during depression (Carver et al., 2008; Plomin & McGuffin, 2003).

In Chapter 14, we will see how drugs that relieve depression tend to make more norepinephrine or serotonin available to the depressed brain. Repetitive physical exercise, such as jogging, which increases serotonin, can have a similar effect (Ilardi, 2009; Jacobs, 1994).

Psychological and Social Influences

Biological influences contribute to depression, but in the nature–nurture dance, thinking and acting also play a part. Recall that life’s experiences may cause epigenetic changes. Our experiences can place molecular tags on our chromosomes, thereby turning genes on or off. Animal studies suggest a role for longlasting epigenetic influences on depression (Nestler, 2011).

Thinking certainly matters, too. The social-cognitive perspective explores how people’s assumptions and expectations influence what they perceive. Depressed people see life through dark glasses. They have intensely negative views of themselves, their situation, and their future. Listen to Norman, a college professor, recalling his depression (Endler, 1982, pp. 45–49).

I [despaired] of ever being human again. I honestly felt subhuman, lower than the lowest vermin. Furthermore, I…could not understand why anyone would want to associate with me, let alone love me…. I was positive that I was a fraud and a phony and that I didn’t deserve my Ph.D…. I didn’t deserve the research grants I had been awarded; I couldn’t understand how I had written books and journal articles…. I must have conned a lot of people.

Expecting the worst, depressed people magnify bad experiences and minimize good ones.

NEGATIVE THOUGHTS AND NEGATIVE MOODS INTERACT Self-defeating beliefs may arise from learned helplessness. As we saw in Chapter 10, both dogs and humans act depressed, passive, and withdrawn after experiencing uncontrollable painful events. Learned helplessness is more common in women, who may respond more strongly to stress (Hankin & Abramson, 2001; Mazure et al., 2002; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2001, 2003). Do you agree or disagree with the statement, “I feel frequently overwhelmed by all I have to do”? In a survey of women and men entering American colleges, 38 percent of the women agreed. Only 17 percent of the men agreed (Pryor et al., 2006). (Did your answer fit that pattern?)

Why are women nearly twice as vulnerable to depression (Kessler, 2001)? This higher risk may relate to women’s tendency to overthink, to brood or ruminate (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2003). Rumination can be adaptive when it helps us focus intently on a problem (Altamirano et al., 2010; Andrews & Thomson, 2009a,b). But when it becomes relentless, self-focused rumination is not adaptive. It diverts us from thinking about other life tasks and leaves us mired in negative emotions (Kuppens et al., 2010).

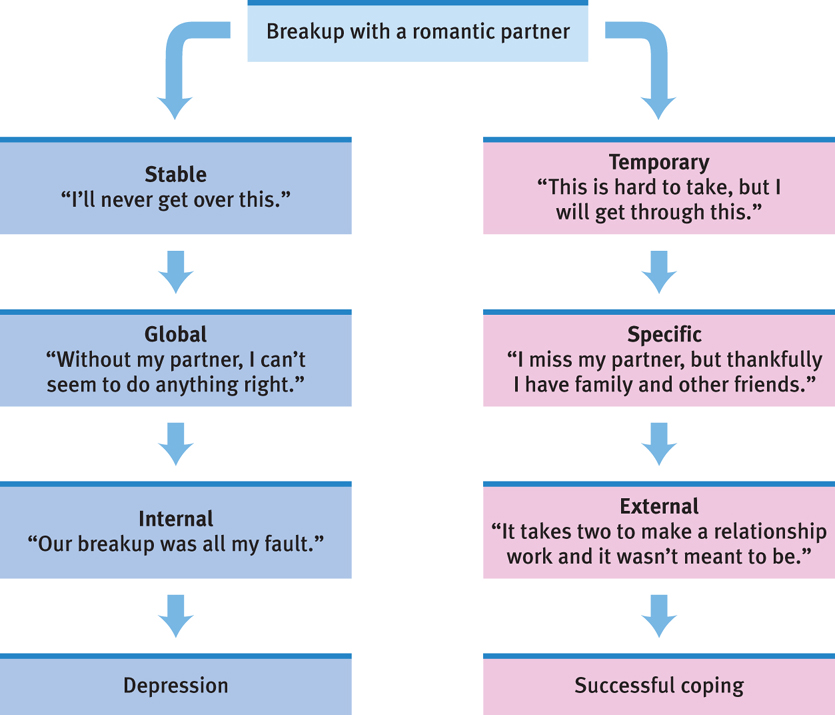

Even so, why do life’s unavoidable failures lead only some people—women and men—and not others to become depressed? The answer lies partly in their explanatory style—who or what they blame for their failures (or credit for their successes). Think how you might feel if you failed a test. If you can blame someone else (“What an unfair test!”), you are more likely to feel angry. If you blame yourself, you probably will feel stupid and depressed.

Depressed people tend to blame themselves. As FIGURE 13.11 illustrates, they explain bad events in terms that are stable (“I’ll never get over this”), global (“I can’t do anything right”), and internal (“It’s all my fault”). Their explanations are pessimistic, overgeneralized, self-focused, and self-blaming. The result may be a depressing sense of hopelessness (Abramson et al., 1989; Panzarella et al., 2006). As Martin Seligman has noted, “A recipe for severe depression is pre existing pessimism encountering failure” (1991, p. 78).

Critics point out a chicken-and-egg problem nesting in the social-cognitive explanation of depression. Which comes first? The pessimistic explanatory style, or the depressed mood? Certainly, the negative explanations coincide with a depressed mood, and they are indicators of depression (Barnett & Gotlib, 1988). But do they cause depression, any more than a speedometer’s reading 70 mph causes a car’s speed? Before or after being depressed, people’s thoughts are less negative. Perhaps a depressed mood triggers negative thoughts. If you temporarily put people in a bad or sad mood, their memories, judgments, and expectations do become more pessimistic.

396

DEPRESSION’S VICIOUS CYCLE Depression, social withdrawal, and rejection feed one another. Depression, as we have seen, is often brought on by events that disrupt our sense of who we are and why we are worthy. The stressful experience may be losing a job, getting divorced or rejected, and suffering physical trauma. Such disruptions in turn lead to brooding, which is rich soil for growing negative feelings. And that negativity—being withdrawn, self-focused, and complaining—can cause others to reject us (Furr & Funder, 1998; Gotlib & Hammen, 1992). Indeed, people with depression are at high risk for divorce, job loss, and other stressful life events. Weary of the person’s fatigue, hopeless attitude, and lethargy, a spouse may threaten to leave, or a boss may begin to question the person’s competence. New losses and stress then plunge the already depressed person into even deeper misery. Misery may love another’s company, but company does not love another’s misery.

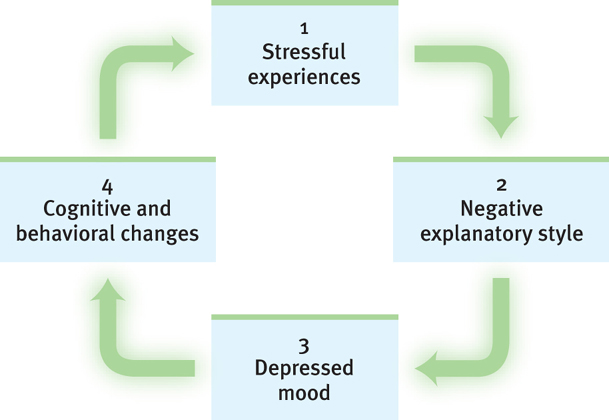

We can now assemble pieces of the depression puzzle (FIGURE 13.12) : (1) Stressful events interpreted through (2) a brooding, negative explanatory style create (3) a hopeless, depressed state that (4) hampers the way the person thinks and acts. These thoughts and actions in turn fuel (1) negative experiences such as rejection. Depression is a snake that bites its own tail.

It is a cycle we can all recognize. When we feel down, we think negatively and remember bad experiences. On the brighter side, each of the four points offers an exit. We could reverse our self-blame and negative outlook. We could turn our attention outward. We could engage in more pleasant activities and more competent behavior.

Britain’s Prime Minister Winston Churchill called depression a “black dog” that periodically hounded him. President Abraham Lincoln was so withdrawn and brooding as a young man that his friends feared he might take his own life (Kline, 1974). As their lives remind us, people can and do struggle through depression. Most regain their capacity to love, to work, to hope, and even to succeed at the highest levels.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 13.12

What does it mean to say that “depression is a whole-body disorder”?

Many factors contribute to depression, including the biological influences of genetics and brain function. Social-cognitive factors also matter, including the interaction of explanatory style, mood, our responses to stressful experiences, and changes in our patterns of thinking and behaving. Depression involves the whole body and may disrupt sleep, energy, and concentration.

397