The Psychological Therapies

Among the dozens of psychotherapies, we will focus on the most influential. Each is built on one or more of psychology’s major theories: psychodynamic, humanistic, behavioral, and cognitive. Most of these techniques can be used one-on-one or in groups. Psychotherapists often use multiple methods. Indeed, many psychotherapists describe their approach as eclectic, using a blend of therapies.

Among the dozens of psychotherapies, we will focus on the most influential. Each is built on one or more of psychology’s major theories: psychodynamic, humanistic, behavioral, and cognitive. Most of these techniques can be used one-on-one or in groups. Psychotherapists often use multiple methods. Indeed, many psychotherapists describe their approach as eclectic, using a blend of therapies.

Psychoanalysis and Psychodynamic Therapy

14-2 What are the goals and techniques of psychoanalysis, and how have they been adapted in psychodynamic therapy?

The first major psychological therapy was Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis. Although few clinicians today practice therapy as Freud did, his work deserves discussion. It helped form the foundation for treating psychological disorders, partly by influencing modern therapists working from the psychodynamic perspective.

The Goals of Psychoanalysis

Freud believed that in therapy, people could achieve healthier, less anxious living by releasing the energy they had previously devoted to id-ego-superego conflicts (Chapter 11). Freud assumed that we do not fully know ourselves. There are threatening things that we seem to want not to know—things we refuse to admit.

411

Freud’s therapy aimed to bring patients’ repressed feelings into conscious awareness. By helping them reclaim their unconscious thoughts and feelings, the therapist (“analyst”) would also help them gain insight into the origins of their disorders. This insight could in turn inspire them to take responsibility for their own growth.

The Techniques of Psychoanalysis

Psychoanalytic theory emphasizes the power of childhood experiences to mold us. Thus, its main method is historical reconstruction. It aims to excavate the past in the hope of loosening its bonds on the present. Like many of his generation, Freud began with hypnosis as a method but discarded it as unreliable. He then turned to free association.

Imagine yourself as a patient (or perhaps with a trusted friend) doing free association. First, you relax. You may lie on a couch or sit in a comfy chair. As the psychoanalyst sits out of your line of vision, you say aloud whatever comes to your mind. At one moment, you’re relating a childhood memory. At another, you’re describing a dream or recent experience.

It sounds easy, but soon you notice how often you edit your thoughts as you speak. You pause for a second before describing how embarrassed you felt giving a class presentation. You leave out details that seemed trivial or shameful. Your mind goes blank as you try to remember an important person or place. You may even joke or change the subject to something less threatening.

To an analyst, these mental blips are blocks that indicate resistance. They hint that anxiety lurks and you are defending against sensitive material. The analyst will note your resistance and then provide insight into its meaning. If offered at the right moment, this interpretation —of, say, your not wanting to talk about your mother or call, text, or message her—may reveal underlying wishes, feelings, and conflicts you are avoiding. The analyst may also offer an explanation of how this resistance fits with other pieces of your psychological puzzle, including those based on an analysis of your dreams.

Multiply that one session by dozens and your relationship patterns will surface in your interactions. You may find you have strong positive or negative feelings for your analyst. The analyst may suggest you are transferring feelings, such as dependency or mingled love and anger, that you experienced in earlier relationships with family members or other important people. By exposing such feelings, you may gain insight into your current relationships.

Relatively few U.S. therapists now offer traditional psychoanalysis. Much of its underlying theory is not supported by scientific research (Chapter 11). Analysts’ interpretations cannot be proven or disproven. And psychoanalysis takes considerable time and money, often years of several expensive sessions each week. Some of these problems have been addressed in the modern psychodynamic perspective that has evolved from psychoanalysis.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 14.1

In psychoanalysis, patients may experience strong feelings for their analyst, which is called ____________. Patients are said to demonstrate anxiety when they put up mental blocks around sensitive memories—showing ____________. The analyst will attempt to provide insight into the underlying anxiety by offering a(n) ____________ of the mental blocks.

transference; resistance; interpretation

412

Psychodynamic Therapy

Those using psychodynamic therapy techniques also aim to dig up their clients’ pasts, but they don’t talk much about id, ego, and superego. Instead, by focusing on themes across important relationships (including childhood experiences and the therapist relationship), they try to help people understand their current symptoms. “We can have loving feelings and hateful feelings toward the same person,” and “we can desire something and also fear it,” noted psychodynamic therapist Jonathan Shedler (2009). Client-therapist meetings take place once or twice a week (rather than several times weekly) for only a few weeks or months (rather than several years). Rather than lying on a couch, out of the therapist’s line of vision, clients meet with their therapist face to face.

In these meetings, clients explore and gain perspective on defended-against thoughts and feelings, as one therapist illustrated with the case of a young man (Shapiro, 1999, p. 8). He had told women that he loved them, knowing well that he didn’t. They expected it, so he said it. But later with his wife, who wished he would say that he loved her, he found he could not do that—“I don’t know why, but I can’t.”

- Therapist: Do you mean, then, that if you could, you would like to?

- Patient: Well, I don’t know…. Maybe I can’t say it because I’m not sure it’s true. Maybe I don’t love her.

Further interactions revealed that the client could not express real love because it would feel “mushy” and “soft” and therefore unmanly. He was “in conflict with himself, and…cut off from the nature of that conflict,” the therapist noted. With such patients, who are estranged from themselves, therapists using psychodynamic techniques “are in a position to introduce them to themselves. We can restore their awareness of their own wishes and feelings, and their awareness, as well, of their reactions against those wishes and feelings” (Shapiro, 1999, p. 8).

Exploring past relationship troubles may help clients understand the origin of their current difficulties. Shedler (2010a) recalled “Jeffrey’s” complaints of difficulty getting along with his colleagues and wife, who saw him as overly critical. When Jeffrey “began responding to me as if I were an unpredictable, angry adversary,” Shedler seized the opportunity to help Jeffrey recognize the relationship pattern. He helped Jeffrey explore the pattern’s roots in the attacks and humiliation he had experienced from his father. Jeffrey was then able to work through and let go of this defensive style of responding to people.

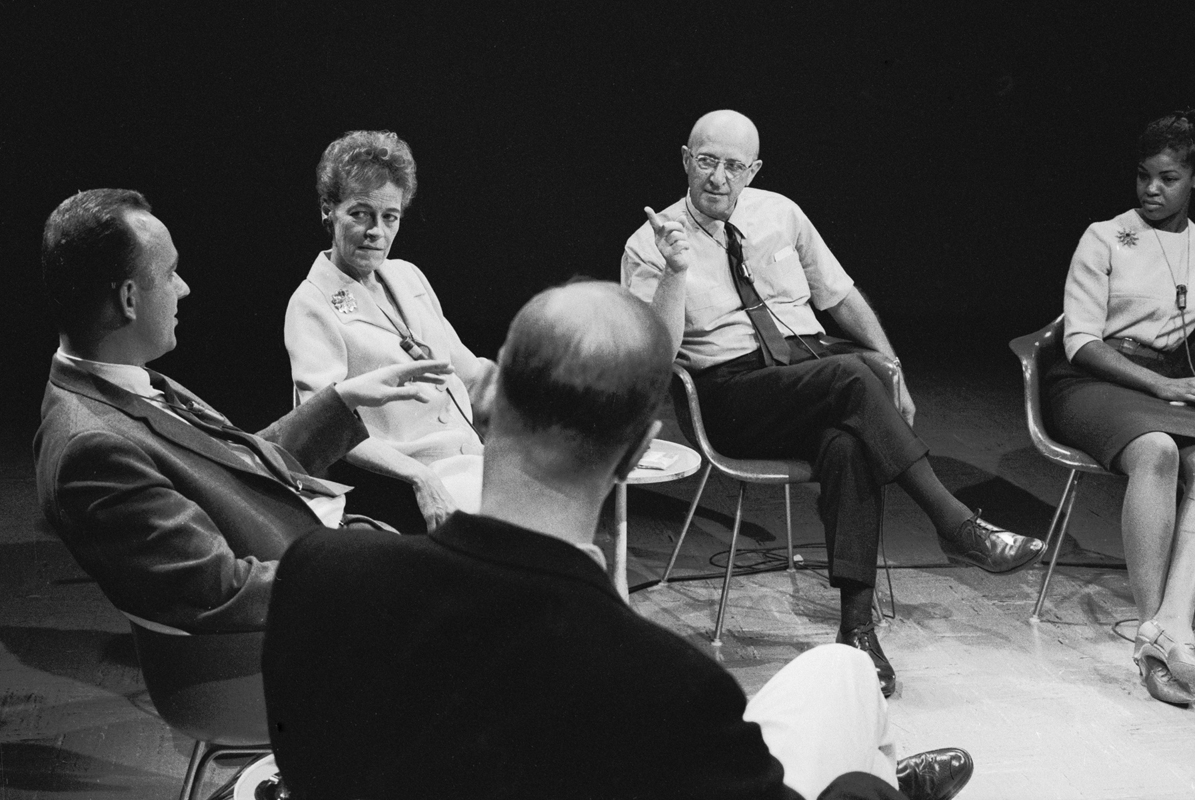

Humanistic Therapies

14-3 What are the basic themes of humanistic therapy, and what are the goals and techniques of Rogers’ client-centered approach?

The humanistic perspective (Chapter 11) has emphasized people’s potential for self-fulfillment. Not surprisingly, humanistic therapies attempt to reduce the inner conflicts that interfere with natural development and growth. To achieve this goal, humanistic therapies try to give people new insights. Indeed, because they share this goal, humanistic and psychodynamic therapies are often referred to as insight therapies. But humanistic therapies differ from psychodynamic therapies in many other ways:

- They aim to boost people’s self-fulfillment by helping them grow in self-awareness and self-acceptance.

- They focus on promoting growth, not curing illness. Thus, those in therapy are called “clients” or just “persons” rather than “patients” (a change many other therapists have adopted).

- The path to growth is taking immediate responsibility for one’s feelings and actions, rather than uncovering hidden causes.

- Conscious thoughts are more important than the unconscious.

- The present and future are more important than the past. Therapy thus focuses on exploring feelings as they occur, rather than gaining insights into the childhood origins of the feelings.

413

All these themes are present in a widely used humanistic technique developed by Carl Rogers (1902–1987). Client-centered therapy, now often called person-centered therapy, focuses on the person’s conscious self-perceptions. It is nondirective—the therapist listens, without judging or interpreting, and refrains from directing the client toward certain insights.

Rogers (1961, 1980) believed that most people already possess the resources for growth. He encouraged therapists to foster growth by exhibiting genuineness, acceptance, and empathy. By being genuine, therapists will express their true feelings. By being accepting, therapists may help clients feel freer and more open to change. By showing empathy, by sensing and reflecting their clients’ feelings, therapists can help clients experience a deeper self-understanding and self-acceptance (Hill & Nakayama, 2000). As Rogers (1980, p. 10) explained,

Hearing has consequences. When I truly hear a person and the meanings that are important to him at that moment, hearing not simply his words, but him, and when I let him know that I have heard his own private personal meanings, many things happen. There is first of all a grateful look. He feels released. He wants to tell me more about his world. He surges forth in a new sense of freedom. He becomes more open to the process of change.

I have often noticed that the more deeply I hear the meanings of the person, the more there is that happens. Almost always, when a person realizes he has been deeply heard, his eyes moisten. I think in some real sense he is weeping for joy. It is as though he were saying, “Thank God, somebody heard me. Someone knows what it’s like to be me.”

To Rogers, “hearing” was active listening. The therapist echoes, restates, and clarifies what the client expresses (verbally or nonverbally). The therapist also acknowledges those expressed feelings. Active listening is now an accepted part of counseling practices in many schools, colleges, and clinics. Counselors listen attentively. They interrupt only to restate and confirm feelings, to accept what was said, or to check their understanding of something. In the following brief excerpt, note how Rogers tried to provide a psychological mirror that would help the client see himself more clearly.

- Rogers: Feeling that now, hm? That you’re just no good to yourself, no good to anybody. Never will be any good to anybody. Just that you’re completely worthless, huh?—Those really are lousy feelings. Just feel that you’re no good at all, hm?

- Client: Yeah. (Muttering in low, discouraged voice) That’s what this guy I went to town with just the other day told me.

- Rogers: This guy that you went to town with really told you that you were no good? Is that what you’re saying? Did I get that right?

- Client: M-hm.

- Rogers: I guess the meaning of that if I get it right is that here’s somebody that meant something to you and what does he think of you? Why, he’s told you that he thinks you’re no good at all. And that just really knocks the props out from under you. (Client weeps quietly.) It just brings the tears. (Silence of 20 seconds)

- Client: (Rather defiantly) I don’t care though.

- Rogers: You tell yourself you don’t care at all, but somehow I guess some part of you cares because some part of you weeps over it. (Meador & Rogers, 1984, p. 167)

Critics ask: Can a therapist be a perfect mirror, without selecting and interpreting what is reflected? Rogers agreed that no one can be totally nondirective. Nevertheless, he said, the therapist’s most important contribution is to accept and understand the client. Given a nonjudgmental, grace-filled environment that provides unconditional positive regard, people may accept even their worst traits and feel valued and whole.

414

How can we develop our own communication strengths by listening more actively in our friendships? Three Rogerian hints may help:

- Summarize. Check your understanding by repeating your friend’s statements in your own words.

- Invite clarification. “What might be an example of that?” may encourage your friend to say more.

- Reflect feelings. “It sounds frustrating” might mirror what you’re sensing from your friend’s body language and emotional intensity.

Behavior Therapies

14-4 How do behavior therapy’s assumptions and techniques differ from those of psychodynamic and humanistic therapies? What techniques are used in exposure therapies and aversive conditioning?

Insight therapies assume that self-awareness and psychological well-being go hand in hand. Psychodynamic therapies expect people’s problems to lessen as they gain insight into their unresolved and unconscious tensions. Humanistic therapies expect people’s problems to lessen as they get in touch with their feelings. Behavior therapies, however, take a different approach. Rather than searching beneath the surface for inner causes, they assume that problem behaviors are the problems. (You can become aware of why you are highly anxious during exams and still be anxious.) By harnessing the power of learning principles, behavior therapies offer clients useful tools for getting rid of unwanted behaviors. They view phobias, for example, as learned behaviors. So why not use conditioning techniques to replace them with new behaviors?

Classical Conditioning Techniques

One cluster of behavior therapies draws on principles developed in Ivan Pavlov’s conditioning experiments (Chapter 6). As Pavlov and others showed, we learn various behaviors and emotions through classical conditioning. If we’re attacked by a dog, we may thereafter have a conditioned fear response when other dogs approach. (Our fear generalizes, and all dogs become conditioned stimuli.)

Could other unwanted responses also be explained by conditioning? If so, might reconditioning be a solution? Learning theorist O. H. Mowrer thought so. He developed a successful conditioning therapy for chronic bedwetters, using a liquid-sensitive pad connected to an alarm. If the sleeping child wets the bed pad, moisture triggers the alarm, waking the child. After a number of trials, the child associates bladder relaxation with waking. In three out of four cases, the treatment has stopped the bed-wetting, and the success has boosted the child’s self-image (Christophersen & Edwards, 1992; Houts et al., 1994).

Let’s broaden the discussion. What triggers your worst fear responses? Public speaking? Flying? Tight spaces? Whatever the trigger, do you think you could unlearn your fear responses? With new conditioning, many people have. An example: The fear of riding in an elevator is often a learned response to the stimulus of being confined in a tight space. Therapists have successfully counterconditioned people with a fear of confined spaces. They pair the trigger stimulus (the enclosed space of the elevator) with a new response (relaxation) that cannot coexist with fear.

To replace unwanted responses with new responses, therapists may use exposure therapies and aversive conditioning.

EXPOSURE THERAPIES Picture the animal you fear the most. Maybe it’s a snake, a spider, or even a cat or a dog. For 3-year-old Peter, it was a rabbit. To rid Peter of his fear of rabbits and other furry objects, psychologist Mary Cover Jones had a plan: Associate the fear-evoking rabbit with the pleasurable, relaxed response associated with eating.

As Peter began his midafternoon snack, she introduced a caged rabbit on the other side of the huge room. Peter, eagerly munching on his crackers and slurping his milk, hardly noticed the furry animal. Day by day, Jones moved the rabbit closer and closer. Within two months, Peter was holding the rabbit in his lap, even stroking it while he ate. His fear of rabbits and other furry objects had disappeared. It had been countered, or replaced, by a relaxed state that could not coexist with fear (Fisher, 1984; Jones, 1924).

Unfortunately for many who might have been helped by Jones’ procedures, her story of Peter and the rabbit did not enter psychology’s lore until psychiatrist Joseph Wolpe (1958; Wolpe & Plaud, 1997) refined Jones’ counterconditioning technique into the exposure therapies used today. These therapies, in a variety of ways, try to change people’s reactions by repeatedly exposing them to stimuli that trigger unwanted reactions. We all experience this process in everyday life. Why would someone who has moved to a new apartment be annoyed by loud traffic sounds nearby but only for a while? With repeated exposure, the person adapts. So, too, with people who have fear reactions to specific events. Exposed repeatedly to the situation that once terrified them, they can learn to react less anxiously (Rosa-Alcázar et al., 2008; Wolitzky-Taylor et al., 2008).

415

William Britten/iStock

One form of exposure therapy widely used to treat phobias is systematic desensitization. You cannot be anxious and relaxed at the same time. Therefore, if you can repeatedly relax when facing anxiety-provoking stimuli, you can gradually eliminate your anxiety. The trick is to proceed gradually. Say you fear public speaking. A therapist might first ask you to make a list of situations that trigger your public speaking anxiety. Your list would range from situations that cause you to feel mildly anxious (perhaps speaking up in a small group of friends) to those that provoke feelings of panic (having to address a large audience).

The therapist would then train you in progressive relaxation. You would learn to relax one muscle group after another. When you have achieved a state of comfortable, complete relaxation, the therapist will ask you to imagine, with your eyes closed, a mildly anxiety-arousing situation—perhaps a mental image of having coffee with a group of friends and trying to decide whether to speak up. You are told to signal, by raising your finger, if you feel any anxiety while imagining this scene. Seeing the signal, the therapist will instruct you to switch off the mental image and go back to deep relaxation. This imagined scene is repeatedly paired with relaxation until you feel no trace of anxiety.

The therapist will then move to the next item on your list, again using relaxation techniques to desensitize you to each imagined situation. After several sessions, you will move to actual situations and practice what you had only imagined before. You will begin with relatively easy tasks and gradually move to more anxiety-filled ones. Conquering your anxiety in an actual situation, not just in your imagination, will raise your self-confidence (Foa & Kozak, 1986; Williams, 1987). Eventually, you may even become a confident public speaker.

If an anxiety-arousing situation is too expensive, difficult, or embarrassing to re-create, the therapist may recommend virtual reality exposure therapy. You would don a head-mounted display unit that projects a three-dimensional virtual world in front of your eyes. The lifelike scenes (which shift as your head turns) would be tailored to your particular fear. Experimentally treated fears include flying, public speaking, particular animals, and heights (Parsons & Rizzo, 2008; Westerhoff, 2007). Those who fear flying can peer out a virtual window of a simulated plane. They feel the engine’s vibrations and hear it roar as the plane taxis down the runway and takes off. In controlled studies, people treated with virtual reality exposure therapy have experienced significant relief from real-life fear (Hoffman, 2004; Krijn et al., 2004; Meyerbröker & Emmelkamp, 2010).

AVERSIVE CONDITIONING Exposure therapies help you learn what you should do. They substitute a relaxed, positive response for a negative response to a harmless stimulus.

Aversive conditioning helps you to learn what you should not do. It substitutes a negative (aversive) response for a positive response to a harmful stimulus.

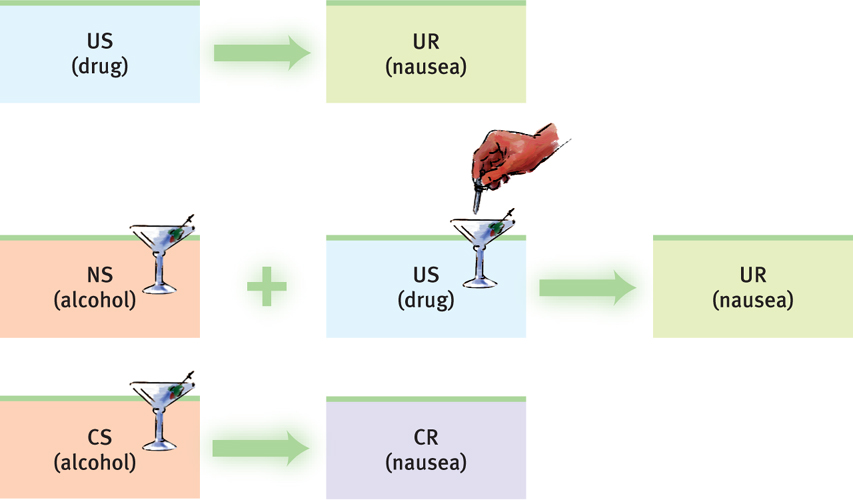

The procedure is simple: Form a new association between the unwanted behavior and unpleasant feelings. Is nail biting the problem? The therapist might suggest painting the fingernails with a yucky-tasting nail polish (Baskind, 1997). Is alcohol abuse the problem? The therapist may offer the client appealing drinks laced with a drug that produces severe nausea. If that therapy links alcohol with violent nausea, the person’s reaction to alcohol may change from positive to negative (FIGURE 14.1).

416

Does aversive conditioning work? In the short run it may. In one classic study, 685 patients with alcohol use disorder completed an aversion therapy program at a hospital (Wiens & Menustik, 1983). Over the next year, they returned for several booster treatments that paired alcohol with sickness. At the end of that year, 63 percent were not drinking alcohol. But after three years, only 33 percent were alcohol free.

Aversive conditioning has a built-in problem: Our thoughts can override conditioning processes (Chapter 6). People know that the alcohol-nausea link exists only in certain situations. This knowledge limits the treatment’s effectiveness. Thus, therapists often combine aversive conditioning with other treatments.

Operant Conditioning

14-5 What is the basic idea of operant conditioning therapies?

If you swim, you know fear. Through trial, error, and instruction, you learned how to put your head underwater without suffocating, how to pull your body through the water, and how to dive safely. Operant conditioning shaped your swimming. You were reinforced for safe, effective behaviors. And you were naturally punished, as when you swallowed water, for improper swimming behaviors.

Remember a basic operant conditioning concept: Consequences drive our behaviors (Chapter 6). Knowing this, therapists can practice behavior modification. They reinforce behaviors they consider desirable. And they do not reinforce, or they sometimes punish, undesirable behavior. Using operant conditioning to solve specific behavior problems has raised hopes for some seemingly hopeless cases. Children with an intellectual disability have been taught to care for themselves. Socially withdrawn children with autism spectrum disorder have learned to interact. People with schizophrenia have learned how to behave more rationally. In each case, therapists used positive reinforcers to shape behavior. In a step-by-step manner, they rewarded behaviors that came closer and closer to the desired behaviors.

In extreme cases, treatment can be intensive. One study worked with 19 withdrawn, uncommunicative 3-year-olds with autism spectrum disorder. For two years, 40 hours each week, the children’s parents attempted to shape their behavior (Lovaas, 1987). They positively reinforced desired behaviors and ignored or punished aggressive and self-abusive behaviors. The combination worked wonders for some children. By first grade, 9 of the 19 were functioning successfully in school and exhibiting normal intelligence. In a control group (not receiving this treatment), only one child showed similar improvement. (Later studies suggested that positive reinforcement without punishment was most effective.)

Not everyone finds the same things rewarding. Hence, the rewards used to modify behavior vary. Some people may respond well to attention or praise. Others require concrete rewards, such as food. Even then, certain foods won’t work as reinforcements for everyone. One of us [ND] finds chocolate neither rewarding nor tasty. Pizza is both, so a nice slice would better shape his behaviors.

To modify behavior, therapists sometimes create a token economy. When people display appropriate behavior, such as getting out of bed, washing, dressing, eating, talking meaningfully, cleaning their rooms, or playing cooperatively, they receive a token or plastic coin. Later, they can exchange a number of these tokens for rewards, such as candy, TV time, day trips, or other privileges. Token economies have worked well in various settings (homes, classrooms, hospitals, institutions for delinquent youth), and among people with various disabilities (Matson & Boisjoli, 2009).

417

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 14.2

How do the insight therapies differ from behavior therapies?

The insight therapies—psychodynamic and humanistic therapies—seek to relieve problems by providing an understanding of their origins. Behavior therapies assume the problem behavior is the problem and treat it directly.

Question 14.3

Some unwanted behaviors are learned. What hope does this fact provide?

If a behavior can be learned, it can be unlearned, and replaced by other more adaptive responses.

Question 14.4

Exposure therapies and aversive conditioning are applications of ____________ conditioning. Token economies are an application of ____________ conditioning.

classical; operant

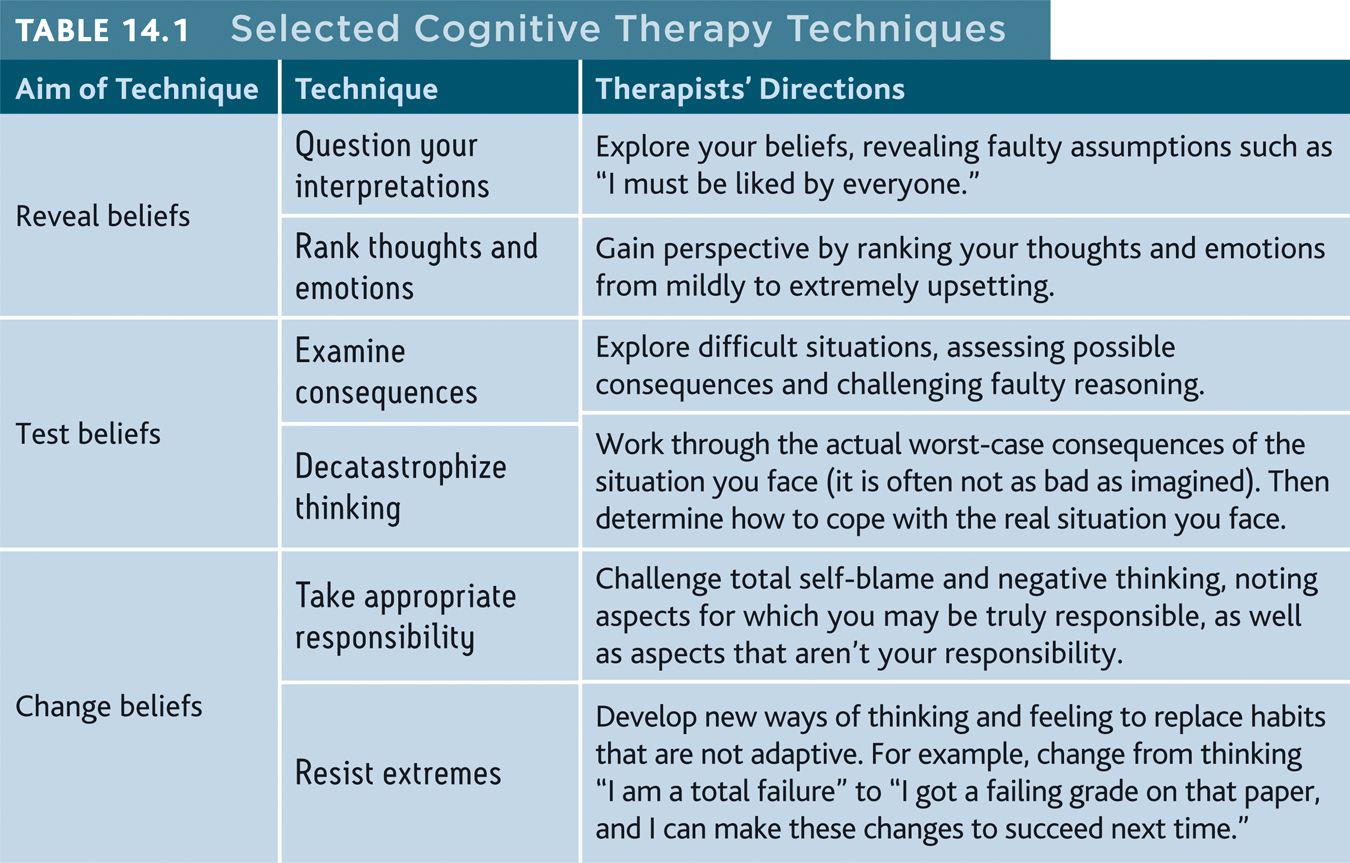

Cognitive Therapies

14-6 What are the goals and techniques of the cognitive therapies and of cognitive-behavioral therapy?

People with specific fears and problem behaviors may respond to behavior therapy. But how would you modify the wide assortment of behaviors that accompany major depression? Or those associated with unfocused anxiety, which doesn’t lend itself to a neat list of anxiety-triggering situations? The same cognitive revolution that influenced other areas of psychology during the last half-century influenced therapy as well.

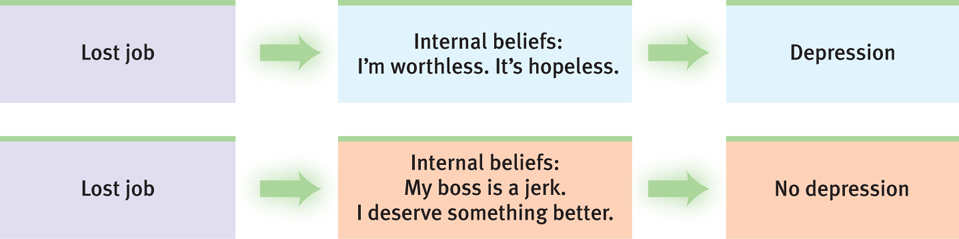

Like psychodynamic approaches, the cognitive therapies assume that our thinking colors our feelings (FIGURE 14.2). Between the event and our response lies the mind. Self-blaming and overgeneralized explanations of bad events are often an important part of the vicious cycle of depression (Chapter 13). If depressed, we may interpret a suggestion as criticism, disagreement as dislike, praise as flattery, friendliness as pity. Dwelling on such thoughts sustains our bad mood and may alienate others. In one classic study, depressed and nondepressed people had a phone conversation with a stranger. Later, that stranger was given the choice of accepting or rejecting them. Depressed people were more often rejected (Coyne, 1976).

Cognitive therapies aim to help people break out of depression’s vicious cycle by adopting new ways of thinking.

Beck’s Therapy for Depression

Many people see the world through rose-colored glasses. They accept more responsibility for their successes than failures. They perceive themselves as above average on most desirable behaviors. And they show unrealistic optimism about their future (recall self-serving bias from Chapter 11). Depressed people occupy a different world, one in which they perceive their own and others’ actions as dark, negative, and pessimistic. Aaron Beck developed cognitive therapy to show depressed clients the irrational nature of their thinking, and to reverse their negative views of themselves, their situations, and their futures.

In Beck’s approach, gentle questioning seeks to reveal irrational thinking and then to persuade people to remove the dark glasses through which they view life (Beck et al., 1979, pp. 145–146):

- Client: I agree with the descriptions of me but I guess I don’t agree that the way I think makes me depressed.

- Beck: How do you understand it?

- Client: I get depressed when things go wrong. Like when I fail a test.

- Beck: How can failing a test make you depressed?

- Client: Well, if I fail I’ll never get into law school.

- Beck: So failing the test means a lot to you. But if failing a test could drive people into clinical depression, wouldn’t you expect everyone who failed the test to have a depression?…Did everyone who failed get depressed enough to require treatment?

- Client: No, but it depends on how important the test was to the person.

- Beck: Right, and who decides the importance?

- Client: I do.

- Beck: And so, what we have to examine is your way of viewing the test (or the way that you think about the test) and how it affects your chances of getting into law school. Do you agree?

- Client: Right.

- Beck: Do you agree that the way you interpret the results of the test will affect you? You might feel depressed, you might have trouble sleeping, not feel like eating, and you might even wonder if you should drop out of the course.

- Client: I have been thinking that I wasn’t going to make it. Yes, I agree.

- Beck: Now what did failing mean?

- Client: (tearful) That I couldn’t get into law school.

- Beck: And what does that mean to you?

- Client: That I’m just not smart enough.

- Beck: Anything else?

- Client: That I can never be happy.

- Beck: And how do these thoughts make you feel?

- Client: Very unhappy.

- Beck: So it is the meaning of failing a test that makes you very unhappy. In fact, believing that you can never be happy is a powerful factor in producing unhappiness. So, you get yourself into a trap—by definition, failure to get into law school equals “I can never be happy.”

“Life does not consist mainly, or even largely, of facts and happenings; it consists mainly of the storm of thoughts that are forever blowing through one’s mind.”

Mark Twain (1835–1910)

We often think in words. Therefore, getting people to change what they say to themselves is an effective way to change their thinking. Have you ever studied hard for an exam but felt extremely anxious before taking it? Many well-prepared students make matters worse with self-defeating thoughts: “This exam is going to be impossible. Everyone else seems so relaxed and confident. I wish I were better prepared. I’m so nervous I’ll forget everything.” Psychologists call this overgeneralized, self-blaming thinking catastrophizing.

To change such negative self-talk, therapists teach people to alter their thinking in stressful situations (Meichenbaum, 1977, 1985). Sometimes it may be enough simply to say more positive things to yourself. “Relax. The exam may be hard, but it will be hard for everyone else, too. I studied harder than most people. Besides, I don’t need a perfect score to get a good grade in this class.” Training people to “talk back” to negative thoughts can be effective. With such training, depression-prone children and adolescents have shown a modestly reduced rate of future depression (Brunwasser et al., 2009; Stice et al., 2009). To a great extent, it is the thought that counts. (For a sampling of commonly used cognitive therapy techniques, see TABLE 14.1.)

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

“The trouble with most therapy,” said therapist Albert Ellis (1913–2007), “is that it helps you to feel better. But you don’t get better. You have to back it up with action, action, action.” Cognitive-behavioral therapy takes a double-barreled approach to depression and other disorders. This widely practiced integrated approach aims not only to alter the way people think but also to alter the way they act. Like other cognitive therapies, it seeks to make people aware of their irrational negative thinking and to replace it with new ways of thinking. Like other behavior therapies, it trains people to practice a more positive approach in everyday settings.

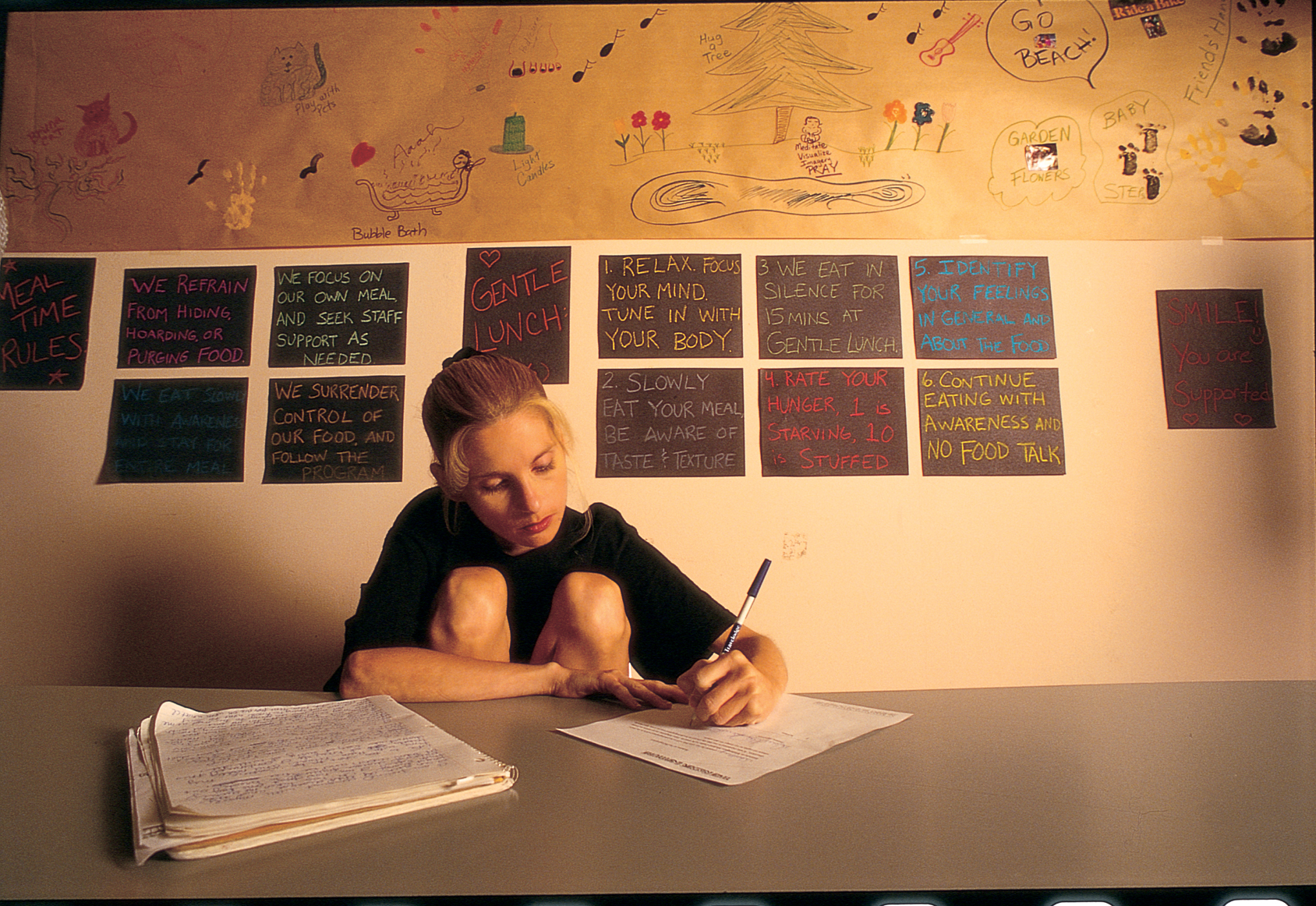

In therapy, people learn to make more realistic appraisals and, as homework, to practice behaviors that counter their problem (Kazantzis et al., 2010a,b; Moses & Barlow, 2006). A person with depression might keep a log of daily situations associated with negative and positive emotions and attempt to engage more in activities that lead to feeling good. Those who fear social situations might practice approaching people.

In one study, people learned to prevent their compulsive behaviors by relabeling their intrusive thoughts (Schwartz et al., 1996). Feeling the urge to wash their hands again, they would tell themselves, “I’m having a compulsive urge.” They would explain to themselves that the hand-washing urge was a result of their brain’s abnormal activity, which they had previously viewed in PET scans. Then, instead of giving in, they would spend 15 minutes in an enjoyable alternative behavior, such as practicing an instrument, taking a walk, or gardening. This helped “unstick” the brain by shifting attention and engaging other brain areas. For two or three months, the weekly therapy sessions continued, with relabeling and refocusing practice at home. By the study’s end, most participants’ symptoms had diminished, and their PET scans revealed normalized brain activity. Other studies confirm cognitive-behavioral therapy’s effectiveness for those with anxiety or depression (Covin et al., 2008).

419

Might clients benefit from participating in cognitive-behavioral therapy over the Internet? Yes, clients can learn cognitive-behavioral skills and can benefit from the therapy over the Internet (Andersson et al., 2012; Kessler et al., 2009; Marks & Cavanaugh, 2009; Stross, 2011). But does therapy over the Internet produce the same benefits as in-person therapy? It’s too early to know. One thing is clear: From Freud’s couch to today’s Internet, the landscape of therapy is changing.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 14.5

How do the humanistic and cognitive therapies differ?

By reflecting clients’ feelings in a nondirective setting, the humanistic therapies attempt to foster personal growth by helping clients become more self-aware and self-accepting. By making clients aware of self-defeating patterns of thinking, cognitive therapies guide people toward more adaptive ways of thinking about themselves and their world.

Question 14.6

What is cognitive-behavioral therapy, and what sorts of problems does this therapy address?

This popular integrative therapy helps people change self-defeating thinking and behavior. It has been shown to be effective for those with obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety disorders, and mood disorders.

Group and Family Therapies

14-7 What are the aims and benefits of group and family therapy?

So far, we have focused on therapies in which one therapist treats one client. Most therapies (though not traditional psychoanalysis) can also occur in small groups. Group therapy does not provide the same degree of therapist involvement with each client. However, it saves therapists’ time and clients’ money, and often is no less effective (Fuhriman & Burlingame, 1994; Jónsson et al., 2011). Therapists frequently suggest group therapy when clients’ problems stem from their interactions with others, as when families have conflicts or an individual’s behavior distresses others. Up to 90 minutes a week, the therapist guides the interactions of 6 to 10 people as they confront issues and react to one another.

The social context of group sessions offers some unique benefits. It can be a relief to find that others, despite their calm appearance, share your problems and your troubling feelings. It can also be helpful to receive feedback as you try out new ways of behaving. Hearing that you look confident, even though you feel anxious and self-conscious, can be very reassuring.

One special type of group interaction, family therapy, assumes that no person is an island. We live and grow in relation to others, especially our family, yet we also work to find an identity outside of our family. These two opposing tendencies can create stress for the individual and the family. This helps explain why therapists tend to view families as systems, in which each person’s actions trigger reactions from others. To change these negative interactions, the therapist often attempts to guide family members toward positive relationships and improved communication.

420

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 14.7

Which therapeutic technique has focused more on the present and future than the past, and has promoted unconditional positive regard and active listening?

humanistic therapy—specifically Carl Rogers’ client-centered (or person-centered) therapy

Question 14.8

Which of the following is NOT a benefit of group therapy?

|

a