Evaluating Psychotherapies

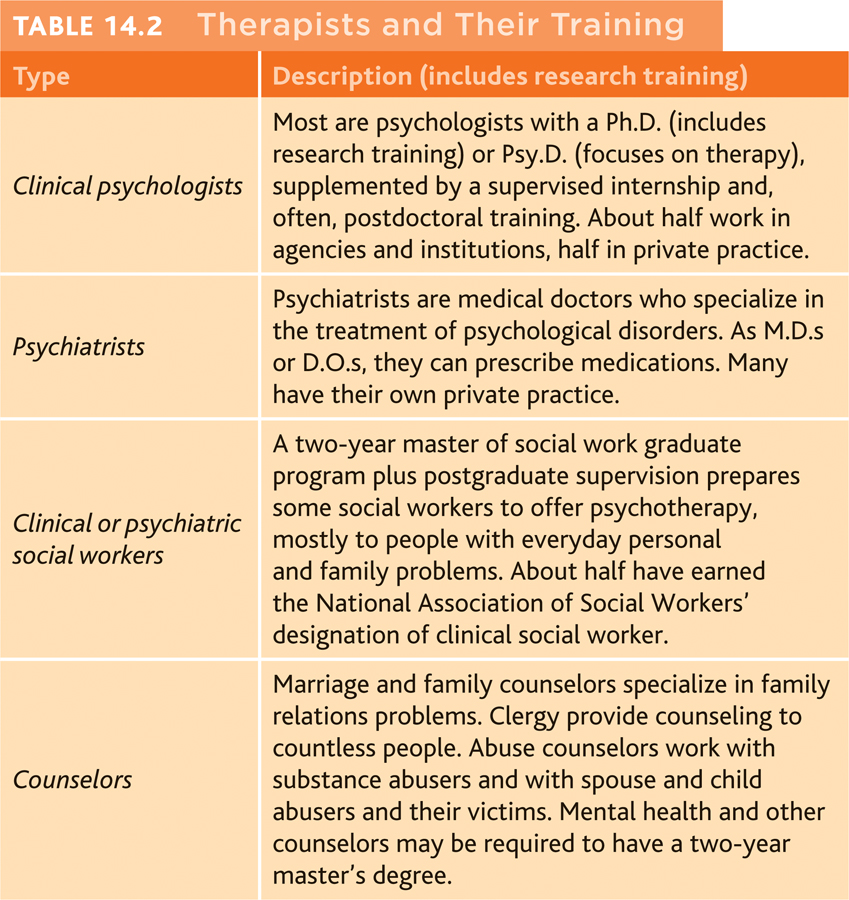

Many Americans have great confidence in psychotherapy’s effectiveness. “Seek counseling” or “Ask your mate to find a therapist,” advice columnists often advise. Before 1950, psychiatrists were the primary providers of mental health care. Today, many others have joined their ranks. Clinical and counseling psychologists offer psychotherapy, and so do clinical social workers; pastoral, marital, abuse, and school counselors; and psychiatric nurses.

Many Americans have great confidence in psychotherapy’s effectiveness. “Seek counseling” or “Ask your mate to find a therapist,” advice columnists often advise. Before 1950, psychiatrists were the primary providers of mental health care. Today, many others have joined their ranks. Clinical and counseling psychologists offer psychotherapy, and so do clinical social workers; pastoral, marital, abuse, and school counselors; and psychiatric nurses.

Is the faith that millions of people place in these therapists justified? As we have seen, history offers examples of ineffective (and occasionally harmful) treatments for psychological disorders. Will psychotherapy join that list? The question, though simply put, is not simply answered.

Is Psychotherapy Effective?

14-8 Does psychotherapy work? Who decides?

Imagine that a loved one, knowing that you’re studying psychology, has asked for your help. She’s been feeling depressed, and she’s thinking about making an appointment with a therapist. She wonders: Does psychotherapy really work? You’ve promised to gather some answers. Where will you start? Who decides whether psychotherapy is effective? Clients? Therapists? Friends and family members?

Clients’ Perceptions

If clients’ glowing comments were the only measuring stick, your job would be easy. Most clients believe that psychotherapy is effective. Consider 2900 Consumer Reports readers who rated their experiences with mental health professionals (1995; Kotkin et al., 1996; Seligman, 1995). How many were at least “fairly well satisfied”? Almost 90 percent (as was Kay Redfield Jamison, as we saw at this chapter’s beginning). Among those who recalled feeling fair or very poor when beginning therapy, 9 in 10 now were feeling very good, good, or at least so-so. We have their word for it—and who should know better?

But clients’ self-reports don’t persuade everyone. Critics point out some reasons for skepticism.

- Clients may need to justify their investment of effort and money. If you invested dozens of hours and lots of money in something, wouldn’t you be motivated to find something positive about it? Psychologists call this effort justification.

- Clients generally speak kindly of their therapists. Even if their problems remain, clients “work hard to find something positive to say. The therapist had been very understanding, the client had gained a new perspective, he learned to communicate better, his mind was eased, anything at all so as not to have to say treatment was a failure” (Zilbergeld, 1983, p. 117).

- People often enter therapy in crisis. Life ebbs and flows. When the crisis passes, people may assume their improvement was a therapy result.

Clinicians’ Perceptions

If clinicians’ perceptions were proof of therapy’s effectiveness, we would have even more reason to celebrate. Case studies of successful treatment abound. Furthermore, therapists are like the rest of us. They treasure compliments from people they’ve tried to help—in this case, clients saying good-bye or later expressing their gratitude. The problem is that clients justify entering psychotherapy by emphasizing their unhappiness. They justify leaving by emphasizing their well-being. And they stay in touch only if satisfied. This means that therapists are most aware of the failures of other therapists—those whose clients, having experienced only temporary relief, are now seeking a new therapist for their recurring problems. Thus, the same person, suffering from the same old anxiety, depression, or marital difficulty, may be a “success” story in several therapists’ files.

Outcome Research

How, then, can we objectively assess psychotherapy’s effectiveness? How can we predict therapy outcomes? What types of people and problems are best helped, and by what type of psychotherapy?

In search of answers, psychologists have turned to controlled research studies. This is a well-traveled path. In the 1800s, skeptical medical doctors began to realize that many patients got better on their own and that most of the fashionable treatments (bleeding, purging) were doing no good. Sorting fact from superstition required following patients and recording outcomes with and without a particular treatment. Typhoid fever patients, for example, often improved after being bled, convincing most doctors that the treatment worked. Then came the shock. A control group was given mere bed rest, and after five weeks of fever, 70 percent improved. The study showed that bleeding was worthless (Thomas, 1992).

421

In the twentieth century, psychology faced a similar challenge. British psychologist Hans Eysenck (1952) launched a spirited debate when he summarized 24 studies of psychotherapy outcomes. He found that two-thirds of those receiving psychotherapy for disorders not involving hallucinations or delusions improved markedly. To this day, no one disputes that optimistic estimate.

Why, then, are we still debating psychotherapy’s effectiveness? Because—as other researchers would later affirm—Eysenck found that untreated people, such as those on waiting lists for the same treatment, had similar rates of improvement. With or without psychotherapy, roughly two-thirds improved noticeably. Time was a great healer.

An uproar greeted Eysenck’s findings. Some critics pointed out errors in his analyses. Others noted that he based his ideas on only 24 studies. Now, more than a half-century later, there are hundreds of such studies. And they confirm that psychotherapy works (Kopta et al., 1999; Leichsenring & Rabung, 2008; Shadish et al., 2000). The best of these studies are randomized clinical trials, in which people on a waiting list are randomly assigned to therapy or to no therapy. Later, the researchers evaluate everyone and compare the outcomes.

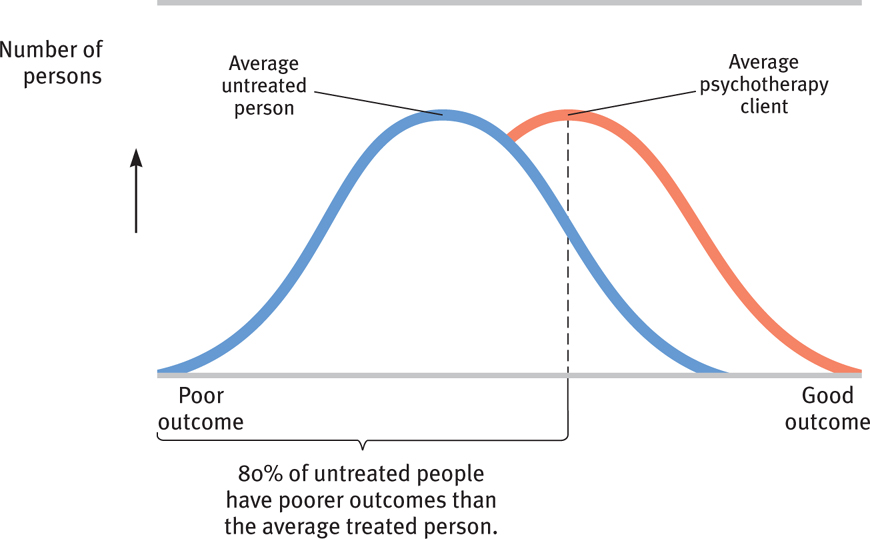

Therapists welcomed the result when the first statistical digest combined the results of 475 of these investigations (Smith et al., 1980). The outcome for the average therapy client was better than that for 80 percent of the untreated people (FIGURE 14.3).

Dozens of such summaries have echoed the results of the earlier outcome studies: Those not undergoing therapy often improve, but those undergoing therapy are more likely to improve.

It’s good to know that psychotherapy, in general at least, is somewhat effective. But distressed people—and those paying for their therapy—really want a different question answered. How effective are particular treatments for specific problems? So what can we tell these people?

Which Psychotherapies Work Best?

14-9 Are some psychotherapies more effective than others for specific disorders?

The early statistical summaries and surveys did not find that any one type of psychotherapy was generally better than others (Smith et al., 1977, 1980). Newer studies have similarly found little connection between clients’ outcomes and their clinicians’ experience, training, supervision, and licensing (Bickman, 1999; Luborsky et al., 2002; Wampold, 2007). A Consumer Reports survey confirmed this result. Were they treated by a psychiatrist, psychologist, or social worker? Were they seen in a group or individual context? Did the therapist have extensive or relatively limited training and experience? It didn’t matter. Clients seemed equally satisfied (Seligman, 1995).

So was the dodo bird in Alice in Wonderland right: “Everyone has won and all must have prizes”? Not quite. Some forms of psychotherapy get prizes for particular problems. Behavior therapies, for example, work well for specific behavior problems, such as bed-wetting, phobias, compulsions, marital problems, and sexual dysfunctions (Bowers & Clum, 1988; Hunsley & Di Giulio, 2002; Shadish & Baldwin, 2005). Psychodynamic therapy has helped treat depression and anxiety (Driessen et al., 2010; Leichsenring & Rabung, 2008; Shedler, 2010b). Cognitive therapies are effective in helping people cope with anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (Aderka et al., 2012; Bisson & Andrew, 2007).

422

But no prizes—and little or no scientific support—would go to certain other psychotherapies (Arkowitz & Lilienfeld, 2006). We would all be wise to avoid the following unsupported approaches:

- Energy therapies, which seek to manipulate people’s invisible energy fields.

- Recovered-memory therapies, which aim to unearth “repressed memories” of early childhood abuse (Chapter 7).

- Rebirthing therapies, which engage people in reenacting their supposed birth trauma.

This list of discredited therapies raises another question. Who should decide which psychotherapies get prizes and which do not? This question lies at the heart of a controversy—some call it psychology’s civil war. What role should science play in clinical practice, and how much should science guide health care providers and insurers in setting payment policies for psychotherapy?

On one side are research psychologists who use scientific methods to extend the list of well-defined therapies with proven results in aiding people with various disorders. They worry that many clinicians “give more weight to their personal experience than to science” (Baker et al., 2008).

On the other side are the nonscientist therapists who view their practices as more art than science. They view psychotherapy as something that cannot be described in a manual or tested in an experiment. People are too complex and psychotherapy is too intuitive for a cookie-cutter approach, many therapists say.

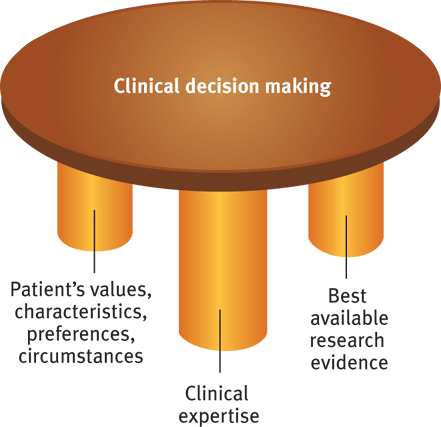

Between these two camps stand the science-oriented clinicians calling for evidence-based practice (FIGURE 14.4). Evidence-based therapists make informed decisions based on research evidence, clinical expertise, and their knowledge of the patient. If we make mental health professionals accountable for effectiveness, everyone gains, say these clinicians. The public will be protected from false therapies. And therapists will be protected from accusations of sounding like snake-oil vendors—“Trust me, I know it works, I’ve seen it work. It will work for you, too.”

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 14.9

Behavior therapy is more likely to be helpful in those with the ________ (most/least) clearly defined problems.

most

Question 14.10

What is evidence-based practice?

Using this approach, therapists make decisions about treatment based on research evidence, clinical expertise, and knowledge of the patient.

How Do Psychotherapies Help People?

14-10 What three elements are shared by all forms of psychotherapy?

Why do therapists’ training and experience appear not to influence clients’ outcomes? The answer seems to be that all psychotherapies offer three basic benefits: hope for demoralized people; a new perspective on oneself and the world; and an empathic, trusting, caring relationship.

Hope for Demoralized People

Many people seek therapy because they feel anxious, depressed, and self-disapproving. They’ve lost their way, and they don’t feel able to turn things around. What any psychotherapy offers is the expectation that things can and will get better. This belief, regardless of therapy technique, can improve morale, create feelings of inner strength, and reduce symptoms (Prioleau et al., 1983). By harnessing the person’s own healing powers, all sorts of treatments—including some folk-healing rites with no scientific support for their effectiveness—may produce cures (Frank, 1982).

A New Perspective

Every psychotherapy also offers people an explanation of their symptoms. Therapy is a new experience that can help people change their behavior and their view of themselves. Psychodynamic therapy, for example, may free people from false beliefs that are rooted in early relationships. Armed with a believable fresh perspective, people may approach life with new energy to make needed changes.

An Empathic, Trusting, Caring Relationship

No matter what technique they use, effective therapists are empathic. They seek to understand people’s experiences. They communicate care and concern. And they earn trust through respectful listening, reassurance, and advice. These qualities were clear in taped therapy sessions from 36 recognized master therapists (Goldfried et al., 1998). Some took a cognitive-behavioral approach. Others emphasized psychodynamic teachings. Regardless, at key moments during the most significant parts of their sessions, they were strikingly similar. They helped clients evaluate themselves, link one aspect of their life with another, and gain insight into their interactions with others. During such interactions, an emotional bond—called the therapeutic alliance—forms between therapist and client. This bond is a key aspect of effective psychotherapy (Klein et al., 2003; Wampold, 2001). In one U.S. National Institute of Mental Health depression-treatment study, the most effective therapists were those who formed the closest therapeutic bonds with their clients by showing empathy and care (Blatt et al., 1996).

423

These three basic benefits—hope, a fresh perspective, and an empathic, caring relationship—help us understand why paraprofessionals (briefly trained caregivers) can assist so many troubled people so effectively (Christensen & Jacobson, 1994). They are an important part of what self-help and support groups offer their members. And they also are part of what traditional healers have offered (Jackson, 1992). Healers everywhere—special people to whom others disclose their suffering, whether psychiatrists, witch doctors, or shamans—have listened in order to understand. And they have empathized, reassured, advised, consoled, interpreted, and explained (Torrey, 1986). These three elements of effective psychotherapy may also explain another finding. People who feel supported by close relationships—who enjoy the fellowship and friendship of caring people—are less likely to need or seek therapy (Frank, 1982; O’Connor & Brown, 1984).

* * *

To recap, people who seek psychotherapy usually improve. So do many of those who do not undergo psychotherapy, and that is a tribute to our human resourcefulness and our capacity to care for one another. Nevertheless, though the therapist’s orientation and experience appear not to matter much, people who receive some psychotherapy usually improve more than those who do not. People with clear-cut, specific problems tend to improve the most.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 14.11

Those who undergo psychotherapy are __________ (more/less) likely to show improvement than those who do not undergo psychotherapy.

more

How Do Culture and Values Influence Psychotherapy?

14-11 How do culture and values influence the client-therapist relationship?

All psychotherapies offer hope. Nearly all therapists try to enhance their clients’ sensitivity, openness, personal responsibility, and sense of purpose (Jensen & Bergin, 1988). But in matters of cultural and moral diversity, therapists differ from one another and may differ from their clients (Delaney et al., 2007; Kelly, 1990).

These differences can create a mismatch when a therapist from one culture interacts with a client from another. In North America, Europe, and Australia, for example, many therapists reflect the majority culture’s individualism, which often gives priority to personal desires and identity. Clients with a collectivist perspective, as with many from Asian cultures, may assume people will be more mindful of others’ expectations. Such clients may have trouble relating to therapies that require them to think only of their individual well-being (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Cultural differences help explain the reluctance of some minority populations to use mental health services and their tendency to leave therapy prematurely (Chen et al., 2009; Sue, 2006). In one experiment, Asian-American clients matched with counselors who shared their cultural values (rather than mismatched with those who did not) perceived more counselor empathy and felt more alliance with the counselor (Kim et al., 2005).

Another area of potential conflict related to values is religion. Highly religious people may prefer and benefit from therapists who share their values and beliefs (Masters, 2010; Smith et al., 2007; Wade et al., 2006). They may have trouble establishing an emotional bond with a therapist who views the world differently.

Albert Ellis, who advocated an aggressive “rational-emotive” therapy, and Allen Bergin, co-editor of the Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, illustrated how sharply psychotherapists can differ. They also show how such differences can affect a therapist’s view of a healthy person.

Ellis (1980) assumed that “no one and nothing is supreme.” “Self-gratification” should be encouraged. “Unequivocal love, commitment, service, and…fidelity to any interpersonal commitment, especially marriage, leads to harmful consequences.”

424

Bergin (1980) viewed things differently: “Because God is supreme, humility and the acceptance of divine authority are virtues.” “Self-control and committed love and self-sacrifice are to be encouraged.” “Infidelity to any interpersonal commitment, especially marriage, leads to harmful consequences.”

Bergin’s and Ellis’ values differed radically. But they agreed on at least one point: Psychotherapists’ personal beliefs and values influence their practice. Clients tend to adopt their therapists’ values (Worthington et al., 1996). For that reason, some psychologists believe therapists should express those values more openly. (For therapy options see Close-Up: A Consumer’s Guide to Psychotherapists.)

CLOSE-UP

A Consumer’s Guide to Psychotherapists

14-12 What should a person look for when selecting a therapist?

Life for everyone is marked by a mix of calm and stress, blessings and losses, good moods and bad. So when should we seek a mental health professional’s help? The American Psychological Association offers these common trouble signals:

- Feelings of hopelessness

- Deep and lasting depression

- Self-destructive behavior, such as alcohol and drug abuse

- Disruptive fears

- Sudden mood shifts

- Thoughts of suicide

- Compulsive rituals, such as hand washing

- Sexual difficulties

- Hearing voices or seeing things that others don’t experience

In looking for a psychotherapist, you may want to have a preliminary meeting with two or three. College health centers are generally good starting points, and they offer some free services. In your meetings, you can describe your problem and learn each therapist’s treatment approach. You can ask questions about the therapist’s values, credentials (TABLE 14.2), state license, and fees. And you can assess your own feelings about each of them. The emotional bond between therapist and client is perhaps the most important factor in effective therapy.

The American Psychological Association recognizes the importance of a strong therapeutic alliance and it welcomes diverse therapists who can relate well to diverse clients. It accredits programs that provide training in cultural sensitivity (for example, to differing values, communication styles, and language) and that recruit underrepresented cultural groups.