Psychology’s Roots

Once upon a time, on a planet in your neighborhood of the universe, there came to be people. These creatures became intensely interested in themselves and one another. They wondered, “Who are we? Why do we think and feel and act as we do? And how are we to understand—and to manage—those around us?”

Once upon a time, on a planet in your neighborhood of the universe, there came to be people. These creatures became intensely interested in themselves and one another. They wondered, “Who are we? Why do we think and feel and act as we do? And how are we to understand—and to manage—those around us?”

To be human is to be curious about ourselves and the world around us. The ancient Greek naturalist and philosopher Aristotle (384–322 B.C.E.) wondered about learning and memory, motivation and emotion, perception and personality. We may chuckle at some of his guesses, like his suggestion that a meal makes us sleepy by causing gas and heat to collect around the source of our personality, the heart. But credit Aristotle with asking the right questions.

Today, psychology asks similar questions. But with its roots reaching back into philosophy and biology, and its branches spreading out across the world, psychology gathers its answers by scientifically studying how we act, think, and feel.

Psychological Science Is Born

1-1 How has psychology's focus changed over time?1

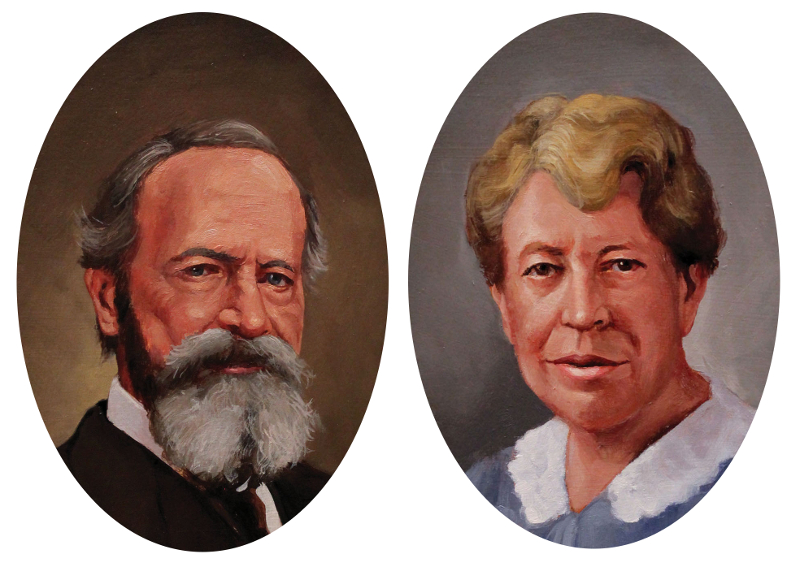

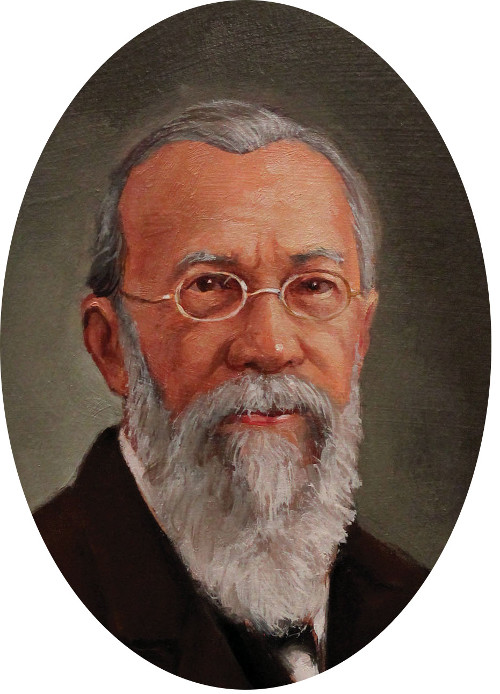

Psychology as we know it was born on a December day in 1879, in a small, third-floor room at a German university. There, Wilhelm Wundt and his assistants created a machine to measure how long it took people to press a telegraph key after hearing a ball hit a platform (Hunt, 1993).2 (Most hit the key in about one-tenth of a second.) Wundt's attempt to measure “atoms of the mind”—the fastest and simplest mental processes—was psychology's first experiment. And that modest third-floor room took its place in history as the first psychological laboratory.

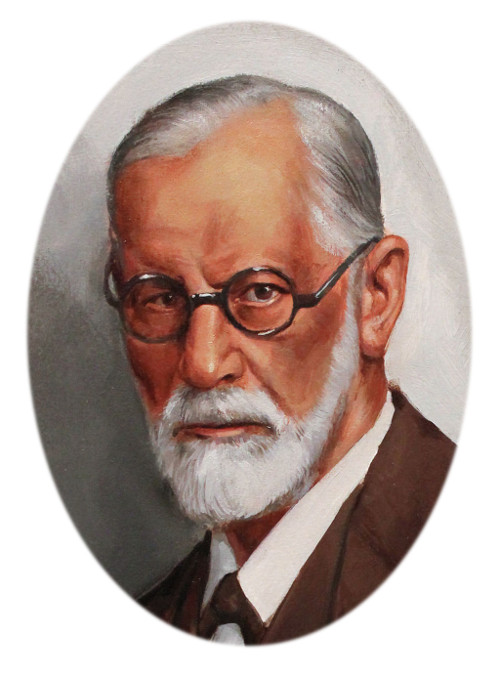

Psychology's earliest pioneers—“Magellans of the mind,” Morton Hunt called them (1993)—came from many disciplines and countries. Wundt was both a philosopher and a physiologist. Charles Darwin, who proposed evolutionary psychology, was an English naturalist. Ivan Pavlov, who taught us much about learning, was a Russian physiologist. Sigmund Freud, a famous personality theorist and therapist, was an Austrian physician. Jean Piaget, who explored children's developing minds, was a Swiss biologist. William James, who shared his love of psychology in his 1890 textbook, was an American philosopher.

Few of psychology's early pioneers were women. In the late 1800s, psychology, like most fields, was a man's world. William James helped break that mold when he accepted Mary Whiton Calkins as his student. Although Calkins went on to outscore all the male students on the Ph.D. exams, Harvard University denied her a degree. In its place, she was told, she could have a degree from Radcliffe College, Harvard's “sister” school for women. Calkins resisted the unequal treatment and turned down the offer. But she continued her research on memory, which her colleagues honored by electing her the first female president of the American Psychological Association (APA). Animal behavior researcher Margaret Floy Washburn became the first woman to receive a psychology Ph.D. and the second, in 1921, to become an APA president.

3

The rest of the story of psychology—the story told by this book—develops at many levels, in the hands of many people, with interests ranging from therapy to the study of nerve cell activity. As you might expect, agreeing on a definition of psychology has not been easy.

For the early pioneers, psychology was defined as “the science of mental life.” And so it continued until the 1920s, when the first of two larger-than-life American psychologists dismissed this idea. John B. Watson, and later B. F. Skinner, insisted that psychology must be “the scientific study of observable behavior.” What you cannot observe and measure, they said, you cannot scientifically study. You cannot observe a sensation, a feeling, or a thought, but you can observe and record people's behavior as they respond to and learn in different situations. Many agreed, and these behaviorists3 and their colleagues were one of psychology's two major forces well into the 1960s.

The other major force was Freudian psychology, which emphasized our unconscious thought processes and our emotional responses to childhood experiences. Some students wonder: Is psychology mainly about Freud's teachings on unconscious sexual conflicts and the mind's defenses against its own wishes and impulses? No. Psychology is much more, though Freudian psychology did have an impact. (In chapters to come, we'll look more closely at Freud and others mentioned here.)

As the behaviorists had rejected the early 1900s definition of psychology, two other groups in the 1960s rejected the behaviorists' definition. The first group, the humanistic psychologists, led by Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow, found both Freudian psychology and behaviorism too limiting. Rather than focusing on childhood memories or learned behaviors, Rogers and Maslow stressed the growth potential of healthy people. They drew attention to ways that an environment can help or hinder our personal growth, and to our needs for love and acceptance.

The second group searching for a new path in psychology pioneered the cognitive revolution, which led the field back to its early interest in mental processes. Cognitive psychology scientifically explores how we perceive, process, and remember information, and even why we can become anxious or depressed. Cognitive neuroscience, with researchers in many disciplines, explores the brain activity underlying mental activity.

To include psychology's concern with observable behavior and with inner thoughts and feelings, today we define psychology as the science of behavior and mental processes.

4

Let's unpack this definition. Behavior is anything a human or nonhuman animal does—any action we can observe and record. Yelling, smiling, blinking, sweating, talking, and questionnaire marking are all observable behaviors. Mental processes are the internal states we infer from behavior—such as thoughts, beliefs, and feelings. For example, I may say that “I feel your pain,” but in fact I infer it from the hints you give me—crying out, clutching your side, and gasping.

The key word in psychology's definition is science. Psychology, as I will stress again and again, is less a set of findings than a way of asking and answering questions. My aim, then, is not merely to report results but also to show you how psychologists play their game, weighing opinions and ideas. I hope you, too, will learn how to play the game—to think smarter when explaining events and making choices in your own life.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

4

Question 1.1

What event defined the start of scientific psychology?

Scientific psychology began in Germany in 1879 when Wilhelm Wundt opened the first psychology laboratory.

Question 1.2

How did the cognitive revolution affect the field of psychology?

It led the field back to its early interest in mental processes and made them acceptable topics for scientific study.

Contemporary Psychology

1-2 What are psychology's current perspectives, and what are some of its subfields?

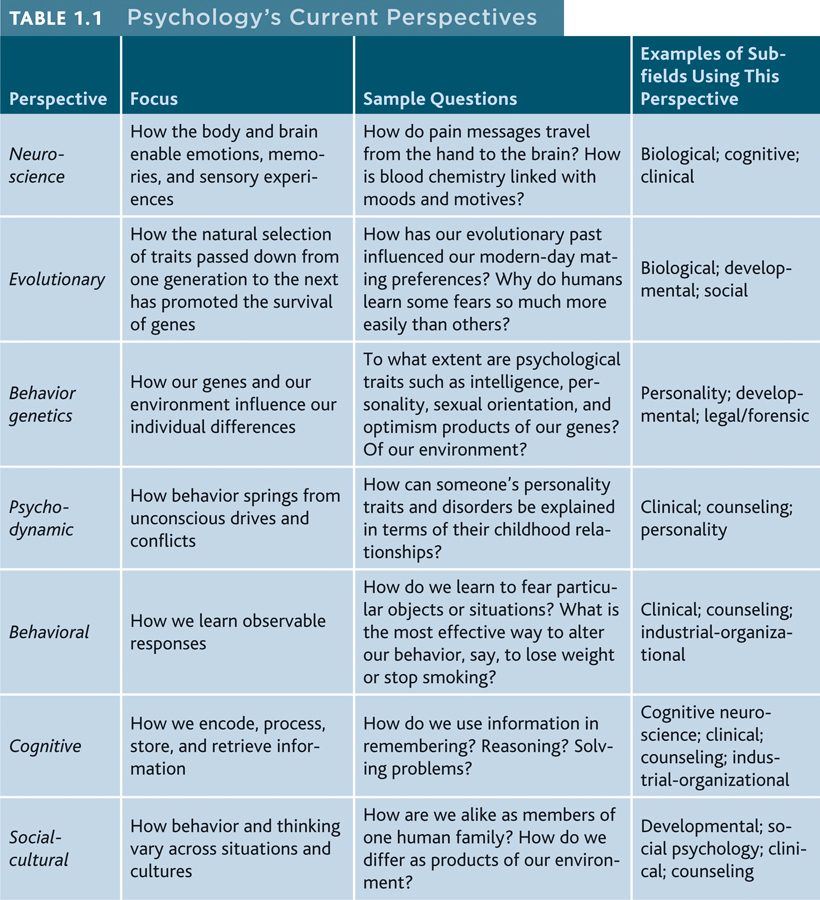

Psychologists' widely ranging interests make it hard to picture a psychologist at work. You might start by imagining a neuroscientist probing an animal's brain, an intelligence researcher studying how quickly infants become bored with a familiar scene, or a therapist listening closely to a client's depressed thoughts. Psychologists examine behavior and mental processes from many viewpoints, which are described in TABLE 1.1. These perspectives range from the biological to the social-cultural, and their settings range from the laboratory to the clinic. But all share a common goal: describing and explaining behavior and the mind underlying it.

5

Psychology also relates to many other fields. You'll find psychologists teaching not only in psychology departments but also in medical schools, law schools, business schools, and theological seminaries. You'll see them working in hospitals, factories, and corporate offices. In this course, you will hear about

- biological psychologists exploring the links between brain and mind.

- developmental psychologists studying our changing abilities from womb to tomb.

- cognitive psychologists experimenting with how we perceive, think, and solve problems.

- personality psychologists investigating our persistent traits.

- social psychologists exploring how we view and affect one another.

- counseling psychologists helping people cope with personal and career challenges by recognizing their strengths and resources.

- health psychologists investigating the psychological, biological, and behavioral factors that promote or impair our health.

- clinical psychologists assessing and treating mental, emotional, and behavior disorders. (By contrast, psychiatrists are medical doctors who also prescribe drugs when treating psychological disorders.)

- industrial-organizational psychologists studying and advising on behavior in the workplace.

Psychology is both a science and a profession. Some of its members conduct basic research, to build the field's knowledge base. Others conduct applied research, tackling practical problems. Many do both. (Want to learn more? See Appendix C, Subfields of Psychology, at the end of this book, and go to the regularly updated Careers in Psychology at www.yourpsychportal.com/myers for more on the many interesting psychology careers available.)

Psychology also influences modern culture. Knowledge transforms us. After learning about psychology's findings, people less often judge psychological disorders as moral failures. They less often regard women as men's inferiors. They less often view children as ignorant, willful beasts in need of taming. And as thinking changes, so do actions. “In each case,” noted Hunt (1990, p. 206), “knowledge has modified attitudes, and, through them, behavior.” Once aware of psychology's well-researched ideas—about how body and mind connect, how we construct our perceptions, how a child's mind grows, how people across the world differ (and are alike)—your own mind may never again be quite the same.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 1.3

The __________ perspective in psychology focuses on how behavior and thought differ from situation to situation and from culture to culture.

social-cultural

Question 1.4

The __________ perspective emphasizes how we learn observable responses.

behavioral