Why Do Psychology?

Many people feel guided by their intuition—by what they feel in their gut. “Buried deep within each and every one of us, there is an instinctive, heart-felt awareness that provides—if we allow it to—the most reliable guide,” offered Britain's Prince Charles (2000).

Many people feel guided by their intuition—by what they feel in their gut. “Buried deep within each and every one of us, there is an instinctive, heart-felt awareness that provides—if we allow it to—the most reliable guide,” offered Britain's Prince Charles (2000).

The Limits of Intuition and Common Sense

1-4 How does our everyday thinking sometimes lead us to the wrong conclusion?

Prince Charles has much company, judging from the long list of pop psychology books on “intuitive managing,” “intuitive trading,” and “intuitive healing.” Intuition is indeed important. Research shows that, more than we realize, our thinking, memory, and attitudes operate automatically, off screen. Like jumbo jets, we fly mostly on autopilot.

“The first principle, is that you must not fool yourself—and you are the easiest person to fool.”

Richard Feynman (1997)

But intuition can lead us astray. Our gut feelings may tell us that lie detectors work and that eyewitnesses recall events accurately. But as you will see in chapters to come, hundreds of findings challenge these beliefs.

Hunches are a good starting point, even for smart thinkers. But thinking critically means checking assumptions, weighing evidence, inviting criticism, and testing conclusions. Does the death penalty prevent murders? Whether your gut tells you Yes or No, you need more evidence. You might ask, Do states with a death penalty have lower homicide rates? After states pass death-penalty laws, do their homicide rates drop? Do homicide rates rise in states that abandon the death penalty? If we ignore the answers to such questions (which the evidence suggests are No, No, and No), our intuition may steer us down the wrong path.

With its standards for gathering and sifting evidence, psychological science helps us avoid errors and think smarter. Before moving on to our study of how psychologists use psychology's methods in their research, let's look more closely at three common flaws in intuitive thinking—hindsight bias, overconfidence, and perceiving patterns in random events.

Did We Know It All Along? Hindsight Bias

Some people think psychology merely proves what we already know and then dresses it in jargon: “So what else is new—you get paid for using fancy methods to tell me what my grandmother knew?” But consider how easy it is to draw the bull's eye after the arrow strikes. After the football game, we credit the coach if a “gutsy play” wins the game and fault the coach for the “stupid play” if it doesn't. After a war or an election, its outcome usually seems obvious. Although history may therefore seem like a series of predictable events, the actual future is seldom foreseen. No one's diary recorded, “Today the Hundred Years War began.”

This hindsight bias (also called the I-knew-it-all-along phenomenon) is easy to demonstrate. Give half the members of a group a true psychological finding, and give the other half an opposite result. Tell the first group, “Psychologists have found that separation weakens romantic attraction. As the saying goes, 'Out of sight, out of mind.'” Ask them to imagine why this might be true. Most people can, and nearly all will then view this true finding as unsurprising—just common sense.

Tell the second group the opposite, “Psychologists have found that separation strengthens romantic attraction. As the saying goes, 'Absence makes the heart grow fonder.'” People given this false statement can also easily explain it, and most will also see it as unsurprising. When two opposite findings both seem like common sense, we have a problem!

10

More than 800 scholarly papers have shown hindsight bias in people young and old from across the world (Roese & Vohs, 2012). Hindsight errors in what we recall and how we explain it show why we need psychological research. Just asking people how and why they felt or acted as they did can be misleading. Why? Not because common sense is usually wrong, but because common sense more easily describes what has happened than what will happen.

Nevertheless, Grandma's intuition is often right. As baseball great Yogi Berra once said, “You can observe a lot by watching.” (We have Berra to thank for other gems, such as “Nobody ever comes here—it's too crowded,” and “If the people don't want to come out to the ballpark, nobody's gonna stop 'em.”) We're all behavior watchers, and sometimes we get it right. Many people believe that love breeds happiness, and it does. (We have what Chapter 9 calls a deep “need to belong.”) But sometimes Grandmother's intuition, informed by countless casual observations, gets it wrong. Psychological research has overturned many popular ideas—that familiarity breeds contempt, that dreams predict the future, and that most of us use only 10 percent of our brain. Research has also surprised us with discoveries we had not predicted—that the brain's chemical messengers control our moods and memories, that other species can pass along their learned habits, that stress affects our ability to fight disease.

Overconfidence

We humans also tend to be overconfident—we think we know more than we do. Consider these three word puzzles (called anagrams), which people like you were asked to unscramble in one study (Goranson, 1978).

WREAT ? WATER

ETRYN ? ENTRY

GRABE ? BARGE

About how many seconds do you think it would have taken you to unscramble each anagram? Knowing the answer makes us overconfident. Surely the solution would take only 10 seconds or so? In reality, the average problem solver spends 3 minutes, as you also might, given a similar puzzle without the solution: OCHSA. (When you're ready, check your answer against the footnote below.5)

Fun anagram solutions from Wordsmith (www.wordsmith.org):

Snooze alarms = Alas! No more z’s

Dormitory = dirty room

Slot machines = cash lost in ’em

Are we any better at predicting our social behavior? At the beginning of the school year, one study had students predict their own behavior (Vallone et al., 1990). Would they drop a course, vote in an upcoming election, call their parents regularly (and so forth)? On average, the students felt 84 percent sure of their self-predictions. But later quizzes about their actual behavior showed their predictions were correct only 71 percent of the time. Even when they were 100 percent sure of themselves, their self-predictions were wrong 15 percent of the time.

Perceiving Order in Random Events

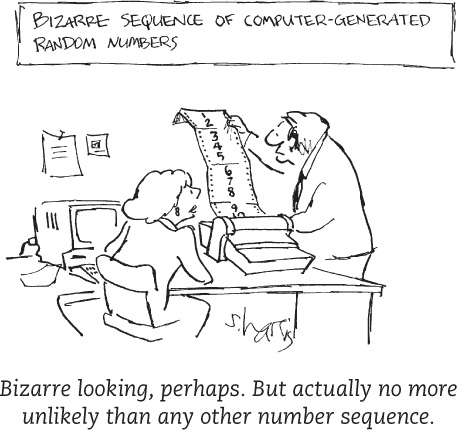

In our natural eagerness to make sense of our world we often perceive patterns. People see a face on the Moon, hear Satanic messages in music, or perceive the Virgin Mary's image on a grilled cheese sandwich. Even in random, unrelated data we often find order, because random sequences often don't look random (Falk et al., 2009; Nickerson, 2002, 2005). In actual random sequences, patterns and streaks (such as repeating numbers) occur more often than people expect (Oskarsson et al., 2009). To demonstrate, I flipped a coin for heads or tails 51 times, with these results:

Looking over the sequence, it's hard not to see what appear to be patterns. Tosses 10 to 22 provided an almost perfect pattern of pairs of tails followed by pairs of heads. On tosses 30 to 38 I had a “cold hand,” with only one head in nine tosses. But my fortunes immediately reversed with a “hot hand”—seven heads out of the next nine tosses. Similar streaks happen—about as often as one would expect in random sequences—in basketball shooting and baseball hitting (Gilovich et al., 1985; Malkiel, 2007; Myers, 2002). These sequences are random but don't look it, so we misread them as being meaningful (“When you're hot, you're hot!”)

11

What explains these streaky patterns? Was I exercising some sort of magical control over my coin? Did I snap out of my tails funk and get in a heads groove? Actually, these are the sort of streaks found in any random data. Comparing each toss to the next, 23 of the 50 comparisons yielded a changed result—just the sort of near 50-50 result we expect from coin tossing. Despite seeming patterns, the outcome of one toss gives no clue to the outcome of the next.

However, some happenings seem so amazing that we struggle to believe they are due to chance. The media often report on unlikely events, and statisticians (who collect and study facts and figures) help to explain them. When Evelyn Marie Adams won the New Jersey lottery twice, newspapers reported the odds of her feat as 1 in 17 trillion. Bizarre? Actually, 1 in 17 trillion are indeed the odds that a given person who buys a single ticket for each of two New Jersey lotteries will win both times. And given the millions of people who buy U.S. State lottery tickets, statisticians reported, it was “practically a sure thing” that someday, someone would hit a state jackpot twice (Samuels & McCabe, 1989). Indeed, offered another statistician team, “with a large enough sample, any outrageous thing is likely to happen” (Diaconis & Mosteller, 1989). An event that happens to but 1 in 1 billion people every day occurs about 7 times a day, over 2500 times a year.

The point to remember: We trust our intuition more than we should. Our intuitive thinking is flawed by three powerful tendencies—hindsight bias, overconfidence, and perceiving patterns in random events. But scientific thinking can help us sift reality from illusion.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 1.7

Why, after friends start dating, do we often feel that we knew they were meant to be together?

We often suffer from hindsight bias—after we've learned a situation's outcome, that outcome seems familiar and therefore obvious.

The Scientific Attitude: Curious, Skeptical, and Humble

1-5 What are the three key elements of the scientific attitude, and how do they support scientific inquiry?

What makes scientific inquiry so useful for detecting truth? The answer lies in three basic attitudes: curiosity, skepticism, and humility.

Underlying all science is, first, a hard-headed curiosity, a passion to explore and understand without misleading or being misled. Some questions (Is there life after death?) are beyond science. Answering them in any way requires a leap of faith. With many other questions (Can some people read minds?), the proof is in the pudding. No matter how crazy an idea sounds, the scientist asks, Does it work? When put to the test, can its predictions be confirmed?

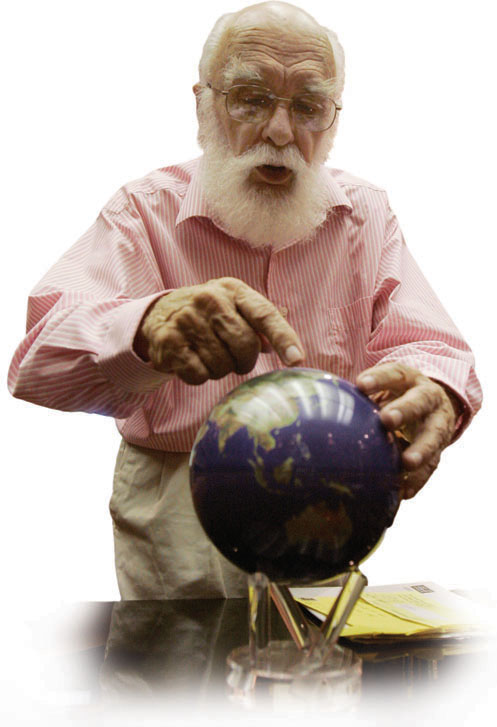

Magician James Randi has used the scientific approach when testing those claiming to see glowing auras around people's bodies:

12

Randi: Do you see an aura around my head?

Aura seer: Yes, indeed.

Randi: Can you still see the aura if I put this magazine in front of my face?

Aura seer: Of course.

Randi: Then if I were to step behind a wall barely taller than I am, you could determine my location from the aura visible above my head, right?

Randi told me that no aura seer has agreed to take this simple test.

When subjected to scientific tests, crazy-sounding ideas sometimes find support. More often, they become part of the mountain of forgotten claims of palm reading, miracle cancer cures, and out-of-body travels. For a lot of bad ideas, science serves as society's garbage disposal.

Sifting reality from fantasy, sense from nonsense, also requires us to be skeptical—not cynical, but also not gullible. “To believe with certainty,” says a Polish proverb, “we must begin by doubting.” As scientists, psychologists greet statements about behavior and mental processes by asking two questions: What do you mean? and How do you know?

When ideas compete, skeptical testing can reveal which ones best match the facts. Do parental behaviors determine children's sexual orientation? Can astrologers predict your future based on the position of the planets at your birth? As you will see in later chapters, putting these two claims to the test has led most psychologists to doubt them.

A scientific attitude is more than curiosity and skepticism, however. It also requires humility—an awareness that we can make mistakes, and a willingness to be surprised and follow new roads. In the end, what matters is not my opinion or yours, but the truths nature reveals in response to our questioning. If people or other animals don't behave as our ideas predict, then so much the worse for our ideas. This humble attitude was expressed in one of psychology's early mottos: “The rat is always right.”

Historians of science tell us that these attitudes—curiosity, skepticism, and humility—helped make modern science possible.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 1.8

“For a lot of bad ideas, science serves as society's garbage disposal.” Describe what this tells us about the scientific attitude.

The scientific attitude combines (1) curiosity about the world around us, (2) skepticism about unproven claims and ideas, and (3) humility about our own understanding. To find out whether an idea matches the facts, psychologists use scientific tests. Ideas that don't hold up will then be discarded.