How Do Psychologists Ask and Answer Questions?

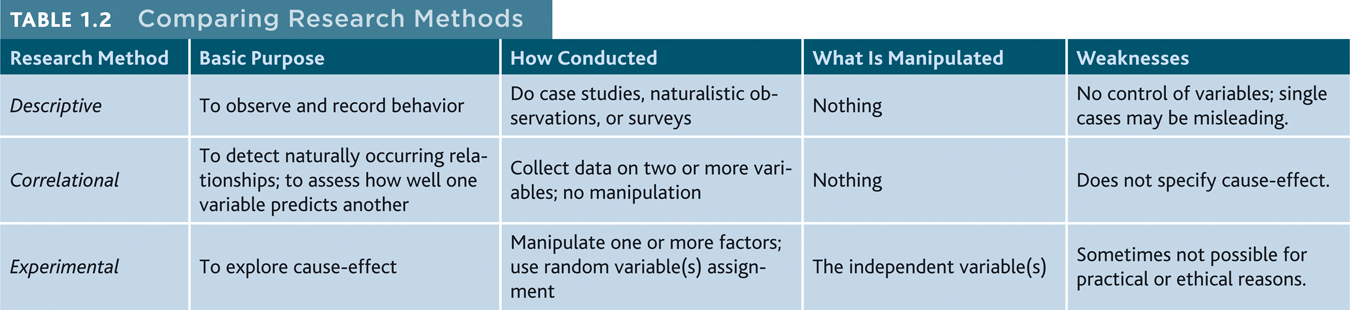

Psychologists transform their scientific attitude into practice by using the scientific method. They observe events, form theories, and then refine their theories in the light of new observations.

Psychologists transform their scientific attitude into practice by using the scientific method. They observe events, form theories, and then refine their theories in the light of new observations.

The Scientific Method

1-6 How do psychological theories guide scientific research?

Chatting with friends and family, we often use theory to mean “mere hunch.” In science, a theory explains behaviors or events by offering ideas that organize what we have observed. By organizing isolated facts, a theory simplifies. There are too many facts about behavior to remember them all. By linking facts to underlying principles, a theory connects many small dots and offers a useful summary so that a clear picture emerges.

A theory about the effects of sleep on memory, for example, helps us organize countless sleep-related observations into a short list of principles. Imagine that we observe over and over that people with good sleep habits tend to answer questions correctly in class, and they do well at test time. We might therefore theorize that sleep improves memory. So far so good: Our principle neatly summarizes a list of facts about the effects of a good night's sleep on memory.

Yet no matter how reasonable a theory may sound—and it does seem reasonable to suggest that sleep could improve memory—we must put it to the test. A good theory produces testable predictions, called hypotheses. Such predictions specify what results (what behaviors or events) would support the theory and what results would cast doubt on the theory. To test our theory about the effects of sleep on memory, our hypothesis might be that when sleep deprived, people will remember less from the day before. To test that hypothesis, we might assess how well people remember course materials they studied before a good night's sleep, or before a shortened night's sleep Figure 1.2. The results will either support our theory or lead us to revise or reject it.

13

Our theories can bias our observations. Having theorized that better memory springs from more sleep, we may see what we expect: We may perceive sleepy people's comments as less insightful.

As a check on their biases, psychologists use operational definitions when they report their studies. “Sleep deprived,” for example, may be defined as “2 or more hours less” than the person's natural sleep. These exact descriptions will allow anyone to replicate (repeat) the research. Other people can then re-create the study with different participants and in different situations. If they get similar results, we can be confident that the findings are reliable.

Let's summarize. A good theory:

- effectively organizes a range of self-reports and observations.

- leads to clear predictions that anyone can use to check the theory.

- often stimulates research that leads to a revised theory which better organizes and predicts what we know. Or, our research may be replicated and supported by similar findings. (This has been the case for sleep and memory studies, as you will see in Chapter 2.)

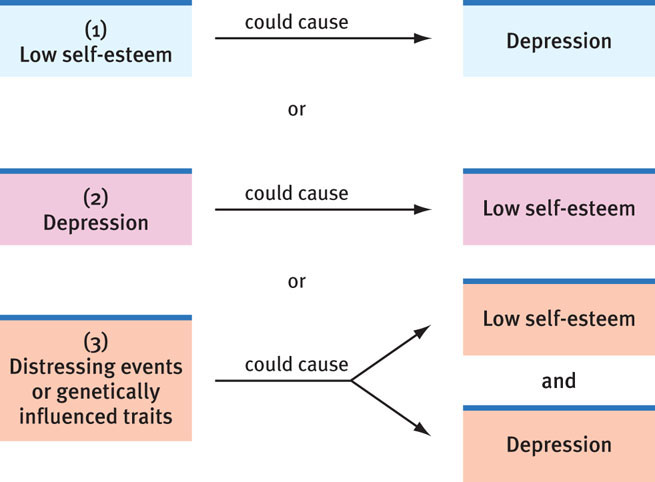

We can test our hypotheses and refine our theories in several ways.

- Descriptive methods describe behaviors, often by using (as we will see) case studies, naturalistic observations, or surveys.

- Correlational methods associate different factors. (You'll see the word factor often in descriptions of research. It refers to anything that contributes to a result.)

- Experimental methods manipulate, or vary, factors to discover their effects.

To think critically about popular psychology claims, we need to understand the strengths and weaknesses of these methods. (For more information about some of the statistical methods that psychological scientists use in their work, see Appendix A, Statistical Reasoning in Everyday Life.)

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 1.9

What does a good theory do?

1. It organizes observed facts. 2. It implies hypotheses that offer testable predictions and, sometimes, practical applications. 3. It often stimulates further research.

Question 1.10

Why is replication important?

Psychologists watch eagerly for new findings, but they also proceed with caution—by awaiting other investigators' repeating the research. Can the finding be confirmed (the result replicated)?

Description

1-7 How do psychologists use case studies, naturalistic observations, and surveys to observe and describe behavior, and why is random sampling important?

In daily life, we all observe and describe other people, trying to understand why they behave as they do. Professional psychologists do much the same, though more objectively and systematically, using

- case studies (in-depth analyses of special individuals).

- naturalistic observations (watching and recording individuals' behavior in a natural setting).

- surveys and interviews (self-reports in which people answer questions about their behavior or attitudes).

The Case Study

A case study examines one individual or group in great depth, in the hope of revealing things true of us all. Some examples: Medical case studies of people who lost specific abilities after damage to certain brain regions gave us much of our early knowledge about the brain. Jean Piaget, the pioneer researcher on children's thinking, carefully watched and questioned just a few children. Studies of only a few chimpanzees jarred our beliefs about what other species can understand and communicate.

Intensive case studies are sometimes very revealing. They often suggest directions for further study, and they show us what can happen. But individual cases may also mislead us. The individual being studied may be atypical (not like those in the larger group). Viewing such cases as general truths can lead to false conclusions. Indeed, anytime a researcher mentions a finding (Smokers die younger: 95 percent of men over 85 are nonsmokers), someone is sure to offer an exception. (Well, I have an uncle who smoked two packs a day and lived to be 89.) These vivid stories, dramatic tales, personal experiences, even psychological case examples—often command attention and are easily remembered. Stories move us, but stories can mislead. As psychologist Gordon Allport (1954, p. 9) said, “Given a thimbleful of [dramatic] facts we rush to make generalizations as large as a tub.”

The point to remember: Individual cases can suggest fruitful ideas. What is true of all of us can be seen in any one of us. But just because something is true of one of us (the atypical uncle), we should not assume it is true of all of us (most long-term smokers suffer ill health and early deaths). We look to methods beyond the case study to uncover general truths.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 1.11

We cannot assume that case studies always reveal general principles that apply to all of us. Why not?

Case studies focus on one individual, so we can't know for sure whether the principles observed would apply to a larger population.

Naturalistic Observation

A second descriptive method records behavior in a natural environment. These naturalistic observations may describe parenting practices in different cultures, students' self-seating patterns in American lunchrooms, or chimpanzee family structures in the wild. New smartphone apps and body-worn sensors hold promise of expanding naturalistic observation. Using such tools, researchers might track willing volunteers—their location, activities, opinions, and even some physical factors—without interfering with the person's activity. One evolutionary psychologist (Miller, 2012) notes, for example, that GPS data “could reveal whether peak-fertility women go out more often to areas with bars and clubs, and Bluetooth scans could reveal whether they go out more often to places with a lot of people.”

In one study, researchers had 52 introductory psychology students don hip-worn tape recorders (Mehl & Pennebaker, 2003). For up to four days, the electronically activated recorders (EARs) captured 30-second snippets of the students' waking hours, turning on every 12.5 minutes. By the end of the study, researchers had eavesdropped on more than 10,000 half-minute life slices. What percentage of the time did these researchers find students talking with someone? What percentage captured students at a computer? The answers: 28 and 9 percent. (What percentage of your waking hours are spent in these activities?)

Like the case study method, naturalistic observation does not explain behavior. It describes it. Nevertheless, descriptions can be revealing.

15

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 1.12

What are the advantages and disadvantages of naturalistic observation, such as the EARs study?

In the EARs study, researchers were able to carefully record and describe naturally occurring behaviors outside the artificial environment of the lab. However, they were not able to explain the behaviors because they could not control all the factors that may have influenced them.

The Survey

A survey looks at many cases in less depth, asking people to report their behavior or opinions. Questions about everything from sexual practices to political opinions are put to the public. In recent surveys,

- half of all Americans reported experiencing more happiness and enjoyment than worry and stress on the previous day (Gallup, 2010).

- 1 in 5 people across 22 countries reported believing that alien beings have come to Earth and now walk among us disguised as humans (Ipsos, 2010b).

- 68 percent of all humans—some 4.6 billion people—say that religion is important in their daily lives (from Gallup World Poll data analyzed by Diener et al., 2011).

But asking questions is tricky, and the answers often depend on the way you word your questions and on who answers them.

WORDING EFFECTS Even subtle changes in the order or wording of questions can have major effects. Should violence be allowed to appear in children's television programs? People are much more likely to approve “not allowing” such things than “forbidding” or “censoring” them. In one national survey, only 27 percent of Americans approved of “government censorship” of media sex and violence, though 66 percent approved of “more restrictions on what is shown on television” (Lacayo, 1995). People are much more approving of “aid to the needy” than of “welfare,” and of “revenue enhancers” than of “taxes.”

Consider two national surveys taken in 2009. In one, 3 in 4 Americans approved of giving people “a choice” of public (government-run) health insurance or private health insurance. Yet in the other survey, most Americans were not in favor of “creating a public health care plan administered by the federal government that would compete directly with private health insurance companies” (Stein, 2009). Wording is a delicate matter. In this case, choice is a word that triggers support. Critical thinkers will reflect on how a question's phrasing might affect the opinions people express.

With very large samples, estimates become quite reliable. E is estimated to represent 12.7 percent of the letters in written English. E, in fact, is 12.3 percent of the 925,141 letters in Melville’s Moby-Dick, 12.4 percent of the 586,747 letters in Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities, and 12.1 percent of the 3,901,021 letters in 12 of Mark Twain’s works (Chance News, 1997).

RANDOM SAMPLING For an accurate picture of a group's experiences and attitudes, there's only one game in town—a representative sample—a smaller group that accurately reflects the larger population you want to study and describe.

So in a survey, how do you obtain a representative sample of, say, the total student population at your school? You would choose a random sample, in which every person in the entire group has an equal chance of being picked. You would not want to ask for volunteers, because those extra-nice students who step forward to help would not necessarily be a random sample of all the students. But you could assign each student a number, and then use a random number generator to select a sample.

Time and money will affect the size of your sample, but you would try to involve as many people as possible. Why? Because large representative samples are better than small ones. (But a small representative sample of 100 is better than an unrepresentative sample of 500.)

Political pollsters sample voters in national election surveys just this way. Using only 1500 randomly sampled people, drawn from all areas of a country, they can provide a remarkably accurate snapshot of the nation's opinions. Without random sampling, large samples—including call-in phone samples and TV or website polls—often merely give misleading results.

The point to remember: Before accepting survey findings, think critically. Consider the question's wording and the sample. The best basis for generalizing is from a random sample of a population.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 1.13

What is an unrepresentative sample, and how do researchers avoid it?

An unrepresentative sample is a survey group that does not represent the population being studied. Random sampling helps researchers form a representative sample because each member of the population has an equal chance of being included.

16

Correlation

1-8 What are positive and negative correlations, and how can they lead to prediction but not cause-effect explanation?

Describing behavior is a first step toward predicting it. Naturalistic observations and surveys often show us that one trait or behavior is related to another. In such cases, we say the two correlate. A statistical measure (the correlation coefficient) helps us figure how closely two things vary together, and thus how well either one predicts the other. Displaying data in a scatterplot (Figure 1.3) can help us see correlations.

- A positive correlation (between 0 and +1.00) indicates a direct relationship, meaning that two things increase together or decrease together. Across people, height correlates positively with weight. The data in Figure 1.3 are positively correlated, because they are generally both rising (moving up and right) together.

- A negative correlation (between 0 and –1.00) indicates an inverse relationship: As one thing increases, the other decreases. The number of hours spent watching TV and playing video games each week correlates negatively with grades. Negative correlations can go as low as –1.00. This means that, like children on opposite ends of a teeter-totter, one set of scores goes down precisely as the other goes up.

- A coefficient near zero is a weak correlation, indicating little or no relationship.

The point to remember: A correlation coefficient helps us see the world more clearly by revealing the extent to which two things relate.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 1.14

Indicate whether each of the following statements describes a positive correlation or a negative correlation.

- The more children and youth used various media, the less happy they were with their lives (Kaiser, 2010). _________

- The more sexual content teens saw on TV, the more likely they were to have sex (Collins et al., 2004). _________

- The longer children were breast-fed, the greater their later academic achievement (Horwood & Ferguson, 1998). _________

- The more income rose among a sample of poor families, the fewer symptoms of mental illness their children experienced (Costello et al., 2003).

1. negative, 2. positive, 3. positive, 4. negative

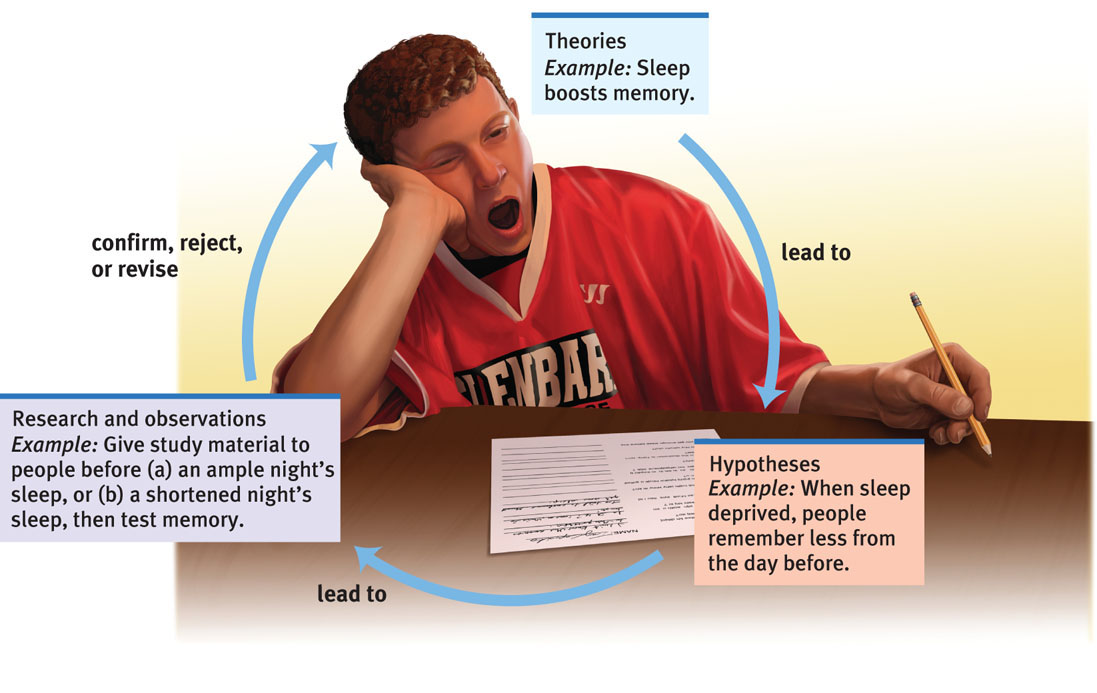

Correlation and Causation

Correlations help us predict. Here's an example: Self-esteem correlates negatively with (and therefore predicts) depression. (The lower people's self-esteem, the more they are at risk for depression.) But does that mean low self-esteem causes depression? If you think the answer is Yes, you are not alone. We all find it hard to resist thinking that associations prove causation. But no matter how strong the relationship, they do not!

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 1.15

Length of marriage correlates with hair loss in men. Does this mean that marriage causes men to lose their hair (or that balding men make better husbands)?

In this case, as in many others, a third factor can explain the correlation: Golden anniversaries and baldness both accompany aging.

17

How else might we explain the negative correlation between self-esteem and depression? As Figure 1.4 suggests, we'd get the same correlation between low self-esteem and depression if depression caused people to be down on themselves. And we'd also get that correlation if something else—a third factor such as heredity or some awful event—caused both low self-esteem and depression.

This point is so important—so basic to thinking smarter with psychology—that it merits one more example, this one from a survey of over 12,000 adolescents. The more those teens felt loved by their parents, the less likely they were to behave in unhealthy ways—having early sex, smoking, abusing alcohol and drugs, behaving violently (Resnick et al., 1997). “Adults have a powerful effect on their children's behavior right through the high school years,” gushed an Associated Press (AP) news report on the study. But no correlation has a built-in cause-effect arrow. Thus, the AP could as well have said, “Well-behaved teens feel their parents' love and approval; out-of-bounds teens more often describe their parents as disapproving.”

The point to remember (turn up the volume here): Correlation indicates the possibility of a cause-effect relationship, but it does not prove causation. Knowing that two events are associated does not tell us anything about which causes the other. Remember this principle and you will be wiser as you read and hear news of scientific studies.

Experimentation

1-9 How do experiments clarify or reveal cause-effect relationships?

Descriptions don't prove causation. Correlations don't prove causation. To isolate cause and effect, psychologists have to simplify the world. In our everyday lives, many things affect our actions and influence our thoughts. Psychologists sort out this complexity by using experiments. With experiments, researchers can focus on the possible effects of one or more factors by

- manipulating the factors of interest.

- holding constant (“controlling”) other factors.

Let's consider a few experiments to see how this works.

Random Assignment: Minimizing Differences

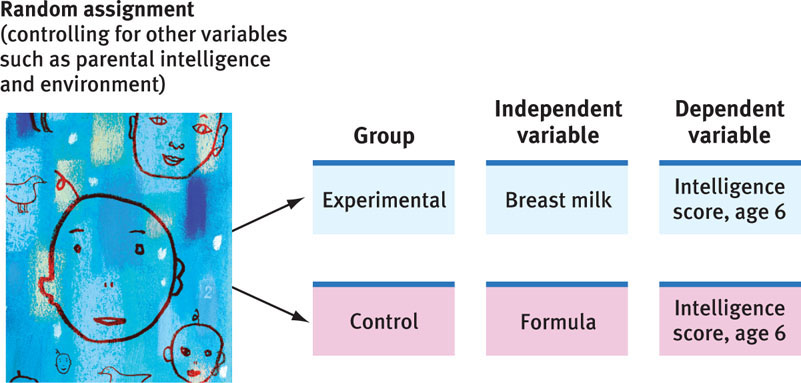

Researchers have compared infants who are breast-fed with those who are bottlefed with formula. Several studies show that children's intelligence test scores are somewhat higher if they were breast-fed (Kramer et al., 2008). Moreover, the longer they were breast-fed, the higher their later scores (Jedrychowski et al., 2012). So we can say that mother's milk correlates modestly but positively with later intelligence. But what does this mean? Do smarter mothers (who in modern countries more often breast-feed) have smarter children? Or do the nutrients in mother's milk contribute to brain development?

18

To find the answer, we would have to isolate the effects of mother's milk from the effects of other factors, such as mother's age, education, and intelligence. How might we do that? By experimenting. With parental permission, one British research team randomly assigned 424 hospital premature infants either to formula feedings or to breast-milk feedings (Lucas et al., 1992). By doing this, they created two otherwise similar groups:

- an experimental group, in which babies received the treatment (breast milk).

- a control group without the treatment.

Random assignment (by flipping a coin, for example) minimizes any preexisting differences between the experimental group and the control group. If one-third of the volunteers for an experiment can wiggle their ears, then about one-third of the people in each group will be ear wigglers. So, too, with mother's age, intelligence, and other characteristics, which will be similar in the experimental and control groups. Thus, if the groups differ at the experiment's end, we can assume that the treatment had an effect.

The British experiment found that breast milk is indeed best for developing intelligence (at least for premature infants). On intelligence tests taken at age 8, those nourished with breast milk scored significantly higher than those formula-fed.

The point to remember: Unlike correlational studies, which uncover naturally occurring relationships, an experiment manipulates (varies) a factor to determine its effect.

Sometimes correlational and experimental studies are used in combination. In one such case, a research team explored the association between pornography use and romantic commitment (Lambert et al., 2012). In one set of studies, the researchers found three correlations. Higher rates of pornography use were associated with (and predicted):

- lower commitment to a partner.

- greater online flirting with others.

- greater infidelity.

A follow-up experiment studied men and women who were in a relationship and reported more than monthly pornography use. Half were randomly assigned to a control group, and they were instructed to “abstain from eating your favorite food or treat for the next three weeks.” The other half (the experimental group) were instructed to abstain from “sexually explicit materials of any kind for the next three weeks.” At the experiment's end, 30 percent of those in the control group predicted they would still be with their romantic partner a year or more into the future, as did 63 percent in the experimental group. “Our research suggests that there is a relationship cost associated with pornography [use],” the researchers concluded.

The Double-Blind Procedure: Eliminating Bias

Thinking back to the breast-milk experiment, we can see how the researchers were lucky—babies don't have expectations that can affect the experiment's outcome. Adults do.

Consider: Three days into a cold, many of us start taking vitamin C tablets. If we find our cold symptoms lessening, we may credit the pills. But after a few days, most colds are naturally on their way out. Was the vitamin C cure truly effective? To find out, we could experiment.

And that is precisely what investigators do to judge whether new drug treatments and new methods of psychotherapy are effective (Chapter 14). Often, the people who take part in these studies are blind (uninformed) about which treatment, if any, they are receiving. The experimental group receives the treatment. The control group receives a placebo (an inactive substance—perhaps a look-alike pill with no drug in it).

Many studies use a double-blind procedure—neither those in the study nor those collecting the data know which group is receiving the treatment. In such studies, researchers can check a treatment's actual effects apart from the participants' belief in its healing powers and the staff's enthusiasm for its potential. Just thinking you are getting a treatment can boost your spirits, relax your body, and relieve your symptoms. This placebo effect is well documented in reducing pain, depression, and anxiety (Kirsch, 2010). Athletes have run faster when given a fake performance-enhancing drug (McClung & Collins, 2007). Drinking decaf coffee has boosted vigor and alertness—for those who thought it had caffeine in it (Dawkins et al., 2011). People have felt better after receiving a phony mood-enhancing drug (Michael et al., 2012). And the more expensive the placebo, the more “real” it seems—a fake pill that costs $2.50 works better than one costing 10 cents (Waber et al., 2008). To know how effective a therapy really is, researchers must control for a possible placebo effect.

19

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 1.16

What measures do researchers use to prevent the placebo effect from confusing their results?

Research designed to prevent the placebo effect randomly assigns participants to an experimental group (which receives the real treatment) or to a control group (which receives a placebo). A comparison of the results will demonstrate whether the real treatment produces better results than belief in that treatment.

Independent and Dependent Variables

Here is an even more potent drug-study example: The drug Viagra was approved for use after 21 clinical trials. One trial was an experiment in which researchers randomly assigned 329 men with erectile disorder to either an experimental group (Viagra takers) or a control group (placebo takers). It was a double-blind procedure—neither the men nor the person who gave them the pills knew which drug they received. The result: Viagra worked. At peak doses, 69 percent of Viagra-assisted attempts at intercourse were successful, compared with 22 percent for men receiving the placebo (Goldstein et al., 1998).

This simple experiment manipulated just one factor—the drug Viagra. We call the manipulated factor an independent variable: We can vary it independently of other factors, such as the men's age, weight, and personality. These other factors, which could influence the experiment's results, are called confounding variables. Thanks to random assignment, those factors should be roughly equal in both groups.

Note the distinction between random sampling (discussed earlier in relation to surveys) and random assignment (depicted in Figure 1.5). Through random sampling, we may represent a population effectively, because each member of that population has an equal chance of being selected (sampled) for participation in our research. Random assignment ensures accurate representation among the research groups, because each participant has an equal chance of being placed in (assigned to) any of the groups. This helps control outside influences so that we can determine cause and effect.

Experiments examine the effect of one or more independent variables on some behavior or mental process that can be measured. We call this kind of affected behavior the dependent variable because it can vary depending on what takes place during the experiment. Experimenters give both variables precise operational definitions. They specify exactly how they are manipulating the independent variable (in this study, the precise drug dosage and timing) and how they are measuring the dependent variable (the questions that assessed the men's responses). These definitions answer the “What do you mean?” question with a level of precision that enables others to repeat the study.

Let's see how this works with the breast-milk experiment Figure 1.5. A variable is anything that can vary (infant nutrition, intelligence). Experiments aim to manipulate an independent variable (infant nutrition), measure the dependent variable (intelligence), and control confounding variables. An experiment has at least two different groups: an experimental group (infants who received breast milk) and a comparison or control group (infants who did not receive breast milk). Random assignment works to control all other (confounding) variables by equating the groups before any manipulation begins. In this way, an experiment tests the effect of at least one independent variable (what we manipulate) on at least one dependent variable (the outcome we measure).

20

Let's pause to check your understanding using another experiment. Psychologists tested whether landlords' perceptions of an applicant's ethnicity would influence the availability of rental housing. The researchers sent identically worded e-mails to 1115 Los Angeles–area landlords (Carpusor & Loges, 2006). They varied the sender's name to imply different ethnic groups: “Patrick McDougall,” “Said Al-Rahman,” and “Tyrell Jackson.” Then they tracked the percentage of positive replies. How many e-mails triggered invitations to view the apartment? For McDougall, 89 percent; for Al-Rahman, 66 percent; and for Jackson, 56 percent.

. . .

Each of psychology's research methods has strengths and weaknesses (TABLE 1.2). Experiments show cause-effect relationships, but some experiments would not be ethical or practical. (To test the effects of parenting, we're just not going to take newborns and randomly assign them either to their biological parents or to orphanages.)

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 1.17

In the rental housing experiment, what was the independent variable? The dependent variable?

The independent variable, which the researchers manipulated, was the set of ethnically distinct names. The dependent variable, which they measured, was the positive response rate.

Question 1.18

Match the term on the left with the description on the right.

|

|

1. c, 2. a, 3. b

Question 1.19

Why, when testing a new drug to control blood pressure, would we learn more about its effectiveness from giving it to half the participants in a group of 1000 than to all 1000 participants?

We learn more about the drug's effectiveness when we can compare the results of those who took the drug (the experimental group) with the results of those who did not (the control group). If we gave the drug to all 1000 participants, we would have no way of knowing whether the drug is serving as a placebo or is actually medically effective.