Prenatal Development and the Newborn

Conception

3-2 How does conception occur, and what are chromosomes, DNA, genes, and the genome? How do genes and the environment interact?

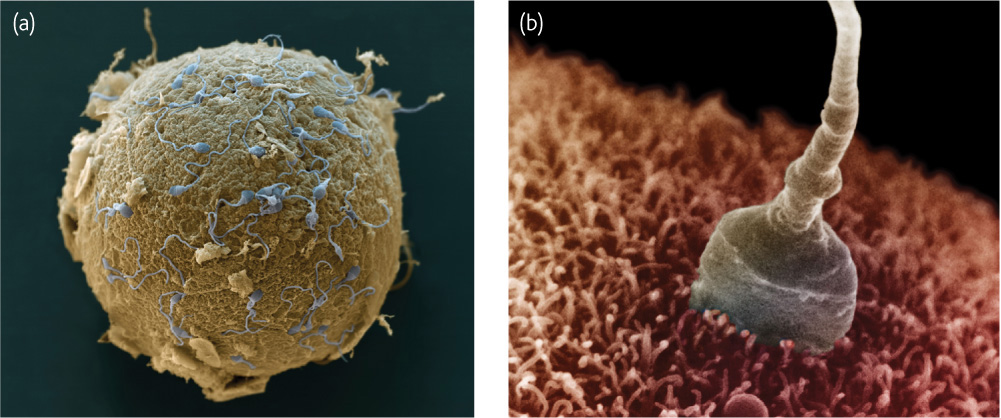

Nothing is more natural than a species reproducing itself, yet nothing is more wondrous. For humans, the process begins when a woman’s ovary releases a mature egg, a cell roughly the size of the period at the end of this sentence. The 200 million or more sperm deposited by the man then begin their race upstream. Like space voyagers approaching a huge planet, the sperm approach a cell 85,000 times their own size. Only a small number will reach the egg. Those that do will release enzymes that eat away the egg’s protective coating (FIGURE 3.1a). As soon as one sperm breaks through that coating (FIGURE 3.1b), the egg’s surface will block out the others. Before half a day passes, the egg nucleus and the sperm nucleus will fuse. The two have become one. Consider it your most fortunate of moments. Among 200 million sperm, the one needed to make you, in combination with that one particular egg, won the race, and so also for each of your ancestors through all human history. Lucky you.

David M. Phillips/Science Source

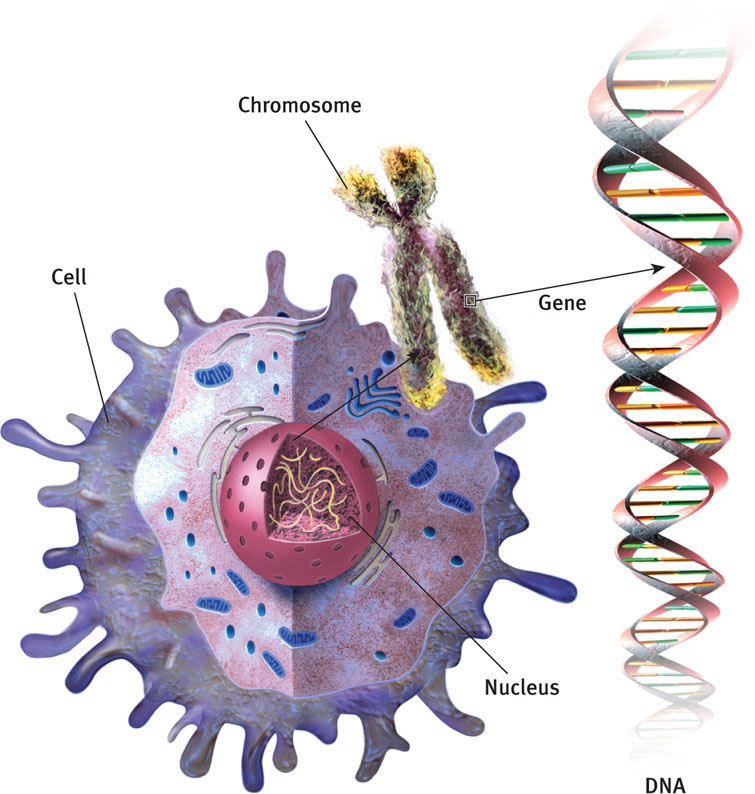

Contained within the new single cell is a master code. This code will interact with your experience, creating you—a being in many ways like all other humans, but in other ways like no other human. Each of your trillions of cells carry this code in its chromosomes. These threadlike structures contain the DNA we hear so much about. Genes are pieces of DNA, and they can be active (expressed) or inactive. External influences can “turn on” genes much as a cup of hot water “turns on” a teabag and lets it “express” its flavor.

When turned on, your genes will provide the code for creating protein molecules, your body’s building blocks. FIGURE 3.2 summarizes these elements that make up your heredity.

Charles Thatcher/The Image Bank/Getty Images

Genetically speaking, every other human is close to being your identical twin. It is our shared genetic profile—our human genome—that makes us humans, rather than chimpanzees or tulips. “Your DNA and mine are 99.9 percent the same,” noted former Human Genome Project director Francis Collins (2007). “At the DNA level, we are clearly all part of one big worldwide family.”

The slight person-to-person variations found at particular gene sites in the DNA give clues to our uniqueness. They help explain why one person has a disease that another does not, why one person is short and another tall, why one is outgoing and another shy. Most of our traits are influenced by many genes. How tall you are, for example, reflects the height of your face, the length of your leg bones, and so forth. Each of those is influenced by different genes. Complex traits such as intelligence, happiness, and aggressiveness are similarly influenced by a whole orchestra of genes (Holden, 2008).

“We share half our genes with the banana.”

Evolutionary biologist Robert May, president of Britain’s Royal Society, 2001

Our human differences are also shaped by our environment—by every external influence, from maternal nutrition while in the womb, to social support while nearing the tomb. Your height, for example, may be influenced by your diet.

How do heredity and environment interact? Let’s imagine two babies with two different sets of genes. Malia is a beautiful child and is also sociable and easygoing. Kalie is plain, shy, and colicky. Malia’s pretty, smiling face attracts more affectionate and stimulating care. This in turn helps her develop into an even warmer and more outgoing person. Kalie’s fussiness often leaves her caretakers tired and stressed. As the two children grow older, Malia, the more naturally outgoing child, often seeks activities and friends that increase her social confidence. Shy Kalie has few friends and becomes even more withdrawn. Our genetically influenced traits affect how others respond. And vice versa, our environments trigger gene activity.

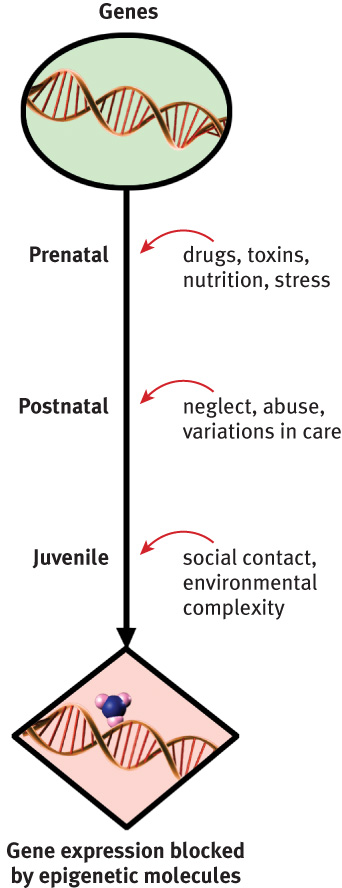

The growing field of epigenetics explores the nature–nurture meeting place. Epigenetics means “in addition to” or “above and beyond” genetics. This field studies how the environment can cause genes to be either active (expressed) or inactive (not expressed). Genes can influence development, but the environment can switch genes on or off.

The molecules that trigger or block genetic expression are called epigenetic marks. When one of these molecules attaches to part of a DNA strand, it instructs the cell to ignore any gene present in that DNA stretch (FIGURE 3.3). Diet, drugs, stress, and other experiences can affect these epigenetic molecules. Thus, from conception onward, heredity and experience dance together.

Prenatal Development

3-3 How does life develop before birth, and how do teratogens put prenatal development at risk?

Fertilized eggs, fewer than half of which survive beyond two weeks, are called zygotes. For the survivors, one cell becomes two, then four—each just like the first—until this cell division has produced some 100 identical cells within the first week. Then the cells begin to specialize. How identical cells do this—as if one decides “I’ll become a brain, you become intestines!”—is a puzzle that scientists are just beginning to solve.

About 10 days after conception, the zygote attaches to the wall of the mother’s uterus. So begins about 37 weeks of the closest human relationship. The tiny clump of cells forms two parts. The inner cells become the embryo (FIGURE 3.4). The outer cells become the placenta, the life-link transferring nutrition and oxygen between embryo and mother. Over the next 6 weeks, the embryo’s organs begin to form and function. The heart begins to beat.

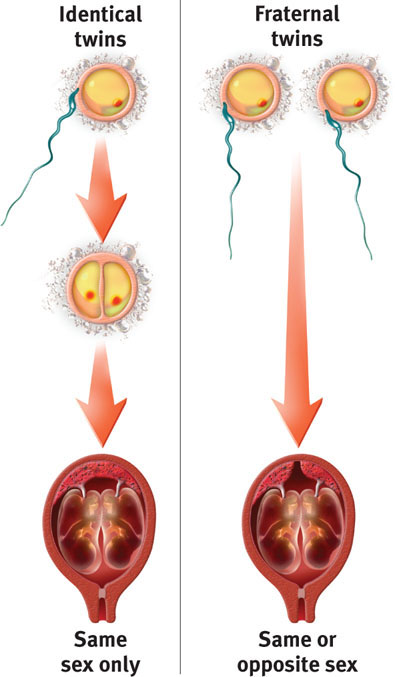

For about 1 in 270 sets of parents there is a bonus. Two heartbeats will reveal that the zygote, during its early days of development, has split into two (FIGURE 3.5). If all goes well, some eight months later two genetically identical babies will emerge from their underwater world.

Identical (monozygotic) twins are nature’s own human clones. They develop from a single fertilized egg, and they share the same genes. They also share the same uterus, and usually the same birth date and cultural history. Fraternal (dizygotic) twins develop from separate fertilized eggs. As wombmates, they share the same prenatal environment but not the same genes. Genetically, they are no more similar than non-twin brothers and sisters. (For more on how psychologists use twin studies to judge the influences of heredity and environment see Close-Up: Twin and Adoption Studies.)

By 9 weeks after conception, an embryo looks unmistakably human. It is now a fetus (Latin for “offspring” or “young one”). During the sixth month, organs will develop enough to give the fetus a good chance of survival if born prematurely.

Remember: Heredity and environment interact. This is true even in the prenatal period. In addition to transferring nutrients and oxygen from mother to fetus, the placenta screens out many harmful substances. But some slip by. Teratogens are agents such as viruses and drugs that can damage an embryo or fetus. This is one reason pregnant women are advised not to drink alcoholic beverages. A pregnant woman never drinks alone. As alcohol enters her bloodstream—and her fetus’—it depresses activity in both their central nervous systems.

Prenatal development

| zygote: | conception to 2 weeks |

| embryo: | 2 weeks through 8 weeks |

| fetus: | 9 weeks to birth |

Even light drinking or occasional binge drinking can affect the fetal brain (Braun, 1996; Ikonomidou et al., 2000; Sayal et al., 2009). Persistent heavy drinking puts the fetus at risk for birth defects and for future behavior and intelligence problems. For 1 in about 800 infants, the effects are visible as fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), marked by lifelong physical and mental abnormalities (May & Gossage, 2001). The fetal damage may occur because alcohol has an epigenetic effect. It leaves chemical marks on DNA that switch genes to abnormal on or off states (Liu et al., 2009).

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 3.1

The first two weeks of prenatal development is the period of the ______. The period of the ______ lasts from 9 weeks after conception until birth. The time between those two prenatal periods is considered the period of the _______.

The first two weeks of prenatal development is the period of the ______. The period of the ______ lasts from 9 weeks after conception until birth. The time between those two prenatal periods is considered the period of the _______.

zygote; fetus; embryo

The Competent Newborn

3-5 What are some of the newborn’s abilities and traits?

Having survived prenatal hazards, we arrive as newborns with automatic reflex responses ideally suited for our survival. (Recall Chapter 2’s discussion of the neural basis of reflexes.) New parents are often in awe of the finely tuned set of reflexes by which their baby gets food. When something touches their cheek, babies turn toward that touch, open their mouth, and actively root for a nipple. Finding one, they quickly close on it and begin sucking. Sucking has its own set of reflexes—tonguing, swallowing, and breathing. Failing to find satisfaction, the hungry baby may cry—a behavior parents find highly unpleasant, and very rewarding to relieve.

Even as newborns, we search out sights and sounds linked with other humans. We turn our heads in the direction of human voices. We prefer to look at objects 8 to 12 inches away. Wonder of wonders, that just happens to be the approximate distance between a nursing infant’s eyes and its mother’s eyes (Maurer & Maurer, 1988). We gaze longer at a drawing of a face-like image (FIGURE 3.6).

We seem especially tuned in to that human who is our mother. Can newborns distinguish their own mother’s smell in a sea of others? Indeed they can. Within days after birth, our brain has picked up and stored the smell of our mother’s body (MacFarlane, 1978). What’s more, that smell preference lasts. One experiment was able to show this, thanks to some French nursing mothers who had used a chamomile-scented balm to prevent nipple soreness (Delaunay-El Allam et al., 2010). Twenty-one months later, their toddlers preferred playing with chamomile-scented toys! Other toddlers who had not sniffed the scent while breast feeding did not show this preference. (This makes me wonder: Will adults, who as babies associated chamomile scent with their mother’s breast, become devoted chamomile tea drinkers?)

Very young infants are competent, indeed. They smell and hear well. They see what they need to see. They are already using their sensory equipment to learn. Guided by biology and experience, those sensory and perceptual abilities will continue to develop steadily over the next months.

Yet, as most parents will tell you after having their second child, babies differ. One clear difference is in temperament, or emotional excitability—whether intense and fidgety, or easygoing and quiet. From the first weeks of life, some babies are difficult: irritable, intense, and unpredictable. Others are easy: cheerful and relaxed, with predictable feeding and sleeping schedules (Chess & Thomas, 1987). Temperament is genetically influenced, and the effect appears in physical differences. Anxious, inhibited infants have high and variable heart rates. They become very aroused when facing new or strange situations (Kagan & Snidman, 2004).

Our biologically rooted temperament also helps form our enduring personality (McCrae et al., 2000, 2007; Rothbart, 2007). This effect can be seen in identical twins, who have more similar personalities—including temperament—than do fraternal twins.

C L O S E - U P

Twin and Adoption Studies

3-4 How do twin and adoption studies help us understand the effects of nature and nurture?In procreation, a woman and a man shuffle their gene decks and deal a life-forming hand to their child-to-be, who is then subjected to countless influences beyond their control. How might researchers tease apart the influences of nature and nurture? To do so, they would need to

- vary the home environment while controlling heredity.

- vary heredity while controlling the home environment. Happily for our purposes, nature has done this work for us.

Identical Versus Fraternal Twins

Identical twins have identical genes. Do these shared genes mean that identical twins also behave more similarly than fraternal twins (Bouchard, 2004)? Studies of some 800,000 twin pairs worldwide provide a consistent answer. Identical twins are more similar than fraternal twins in their abilities, personal traits, and interests (Johnson et al., 2009; Loehlin & Nichols, 1976).

Next question: Could shared experiences rather than shared genes explain these similarities? Again, studies of twin pairs give some answers.

Separated Twins

On a chilly February morning in 1979, some time after divorcing his first wife, Linda, Jim Lewis awoke next to his second wife, Betty. Determined that this marriage would work, Jim left love notes to Betty around the house. As he lay there he thought about his son, James Alan, and his faithful dog, Toy.

Jim loved his basement woodworking shop where he built furniture, including a white bench circling a tree. Jim also liked to drive his Chevy, watch stock-car racing, and drink Miller Lite beer. Except for an occasional migraine, Jim was healthy. His blood pressure was a little high, perhaps related to his chain-smoking. He had gained weight but had shed some of the extra pounds. After a vasectomy, he was done having children.

What was extraordinary about Jim Lewis, however, was that at that moment (I am not making this up) there was another man named Jim for whom all these things were also true.1 This other Jim—Jim Springer—just happened, 38 years earlier, to have been Jim Lewis’ wombmate. Thirty-seven days after their birth, these genetically identical twins were separated and adopted by two blue-collar families. They grew up with no contact until the day Jim Lewis received a call from his genetic clone (who, having been told he had a twin, set out to find him).

One month later, the brothers became the first of 137 separated twin pairs tested by psychologist Thomas Bouchard and his colleagues (Miller, 2012). Given tests measuring their personality, intelligence, heart rate, and brain waves, the Jim twins were virtually as alike as the same person tested twice. Their voice patterns were so similar that, hearing a playback of an earlier interview, Jim Springer guessed “That’s me.” Wrong—it was his brother.

This and other research on separated identical twins supports the idea that genes matter.

Twin similarities do not impress Bouchard’s critics, however. If any two strangers were to spend hours comparing their behaviors and life histories, wouldn’t they also discover many coincidental similarities? Moreover, critics note, identical twins share an appearance and the responses it evokes, so they have probably had similar experiences. Bouchard replies that the life choices made by separated fraternal twins are not as dramatically similar as those made by separated identical twins.

Biological Versus Adoptive Relatives

The separated-twin studies control heredity while varying environment. Nature’s second type of real-life experiment—adoption—controls environment while varying heredity. Adoption creates two groups: genetic relatives (biological parents and siblings) and environmental relatives (adoptive parents and siblings). For any given trait we study, we can therefore ask three questions:

- How much do adopted children resemble their biological parents, who contributed their genes?

- How much do they resemble their adoptive parents, who contribute a home environment?

- While sharing a home environment, do adopted siblings also come to share traits?

By providing children with loving, nurturing homes, adoption matters. Yet researchers asking these questions about personality agree on one stunning finding, based on studies of hundreds of adoptive families. Non-twin siblings who grow up together, whether biologically related or not, do not much resemble one another in personality (McGue & Bouchard, 1998; Plomin et al., 1998; Rowe, 1990). In traits such as outgoingness and agreeableness, adoptees are more similar to their biological parents than to their caregiving adoptive parents. This heredity effect shows up in macaque monkeys’ personalities as well (Maestripieri, 2003).

In the pages to come, twin and adoption study results will shed light on how nature and nurture interact to influence intelligence, disordered behavior, and many other traits.

1. Actually, this description of the two Jims errs in one respect: Jim Lewis named his son James Alan. Jim Springer named his James Allan.