Infancy and Childhood

As a flower develops in accord with its genetic instructions, so do we humans. Maturation—the orderly sequence of biological growth—dictates much of our shared path. We stand before we walk. We use nouns before adjectives. Severe deprivation or abuse can slow our development, but the genetic growth tendencies are inborn. Maturation (nature) sets the basic course of development; experience (nurture) adjusts it. Once again, we see genes and scenes interacting.

Physical Development

3-6 How do the brain and motor skills develop during infancy and childhood?

Brain Development

In your mother’s womb, your developing brain formed nerve cells at the explosive rate of nearly one-quarter million per minute. From infancy on, your brain and your mental abilities developed together. On the day you were born, you had most of the brain cells you would ever have. However, the wiring among these cells—your nervous system—was immature. After birth, these neural networks had a wild growth spurt, branching and linking in patterns that would eventually enable you to walk, talk, and remember.

From ages 3 to 6, the most rapid brain growth was in your frontal lobes, the seat of reasoning and planning. During those years, your ability to control your attention and behavior developed rapidly (Garon et al., 2008; Thompson-Schill et al., 2009). Your frontal lobes continued developing into adolescence and beyond. Last to develop are the association areas—those linked with thinking, memory, and language. As they develop, mental abilities surge (Chugani & Phelps, 1986; Thatcher et al., 1987).

“It is a rare privilege to watch the birth, growth, and first feeble struggles of a living human mind.”

Annie Sullivan, in Helen Keller’s The Story of My Life, 1903

The neural pathways supporting language and agility continue their rapid growth into puberty. Then, a use-it-or-lose-it pruning process shuts down unused links and strengthens others (Paus et al., 1999; Thompson et al., 2000).

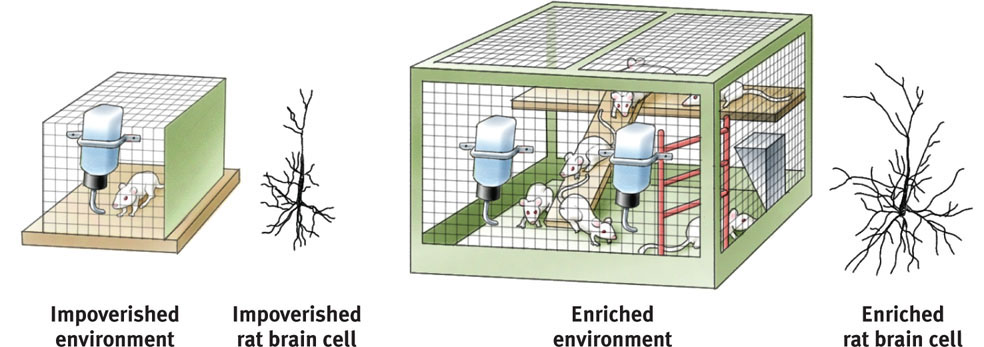

Your genes laid down the basic design of your brain, rather like the lines of a coloring book, but experience fills in the details (Kenrick et al., 2009). So how do early experiences shape the brain? Researchers opened a window on that process in experiments that separated young rats into two groups (Rosenzweig, 1984; Renner & Rosenzweig, 1987). Rats in one group lived alone, with little to interest or distract them. The other rats shared a cage, complete with objects and activities that might exist in a natural “rat world” (FIGURE 3.7). In this enriched environment, rats developed a heavier and thicker brain cortex.

The environment’s effect was so great that if you viewed brief video clips, you could tell from the rats’ activity and curiosity whether they had lived in solitary confinement or in the enriched setting (Renner & Renner, 1993). After 60 days in the enriched environment, some rats’ brain weight increased 7 to 10 percent. The number of synapses, forming the networks between the cells (see FIGURE 3.7), mushroomed by about 20 percent (Kolb & Whishaw, 1998).

Touching or massaging infant rats and premature human babies has similar benefits (Field, 2010). In hospital intensive care units, medical staff now massage premature infants to help them develop faster neurologically, gain weight more rapidly, and go home sooner.

Nature and nurture together sculpt our synapses. Brain maturation provides us with a wealth of neural connections. Experience—sights and smells, touches and tugs—activate and strengthen some neural pathways while others weaken from disuse. Similar to paths through a forest, less-traveled neural pathways gradually disappear and popular ones are broadened.

During early childhood—while excess connections are still available—youngsters can most easily master such skills as the accent and correct order of words of another language. We seem to have a critical period for some skills. Lacking any exposure to spoken, written, or signed language before adolescence, a person will never master any language (see Chapter 8). Likewise, lacking visual experience during the early years, a person whose vision is restored by cataract removal will never achieve normal perceptions (more on this in Chapter 5). Without stimulation, the brain cells normally assigned to vision will die during the pruning process or be used for other purposes. For normal brain development, early stimulation is critical. The maturing brain’s rule: Use it or lose it.

The brain’s development does not, however, end with childhood. Throughout life, whether we are learning to text friends or write textbooks, we perform with increasing skill as our learning changes our brain tissue (Ambrose, 2010).

Motor Development

As their nervous system and muscles mature, babies gain greater control over their movements. Motor skills emerge, and with occasional exceptions, their sequence is universal. Babies roll over before they sit unsupported. They usually crawl on all fours before they walk. The recommended infant back-to-sleep position (putting babies to sleep on their backs to reduce the risk of a smothering crib death) has been associated with somewhat later crawling but not with later walking (Davis et al., 1998; Lipsitt, 2003).

There are, however, individual differences in timing. Consider walking. In the United States, 90 percent of all babies walk by age 15 months. But 25 percent walk by 11 months, and 50 percent within a week after their first birthday (Frankenburg et al., 1992).

Genes guide motor development. Identical twins typically begin walking on nearly the same day (Wilson, 1979). The rapid development of the cerebellum (at the back of the brain; see Chapter 2) helps create our eagerness to walk at about age 1. Maturation is likewise important for mastering other physical skills, including bowel and bladder control. Before a child’s muscles and nerves mature, no amount of pleading or punishment will produce successful toilet training.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 3.2

The biological growth process, called ______, explains why most children begin walking by about 12 to 15 months.

The biological growth process, called ______, explains why most children begin walking by about 12 to 15 months.

maturation

Brain Maturation and Infant Memory

Can you recall your first day of preschool or your third birthday party? Most people cannot. Psychologists call this blank space in our conscious memory infantile amnesia. Although we consciously recall little from before age 4, our brain was processing and storing information during that time. How do we know that? To see how developmental psychologists study thinking and learning in very young children, consider a surprise discovery.

In 1965, Carolyn Rovee-Collier was finishing her doctoral work in psychology. She was a new mom, whose colicky 2-month-old, Benjamin, could be calmed by moving a mobile hung above his crib. Weary of hitting the mobile, she strung a cloth ribbon connecting the mobile to Benjamin’s foot. Soon, he was kicking his foot to move the mobile.

Thinking about her unintended home experiment, Rovee-Collier realized that, contrary to popular opinion in the 1960s, babies are capable of learning. To know for sure that little Benjamin wasn’t just a whiz kid, Rovee-Collier repeated the experiment with other infants (Rovee-Collier, 1989, 1999). Sure enough, they, too, soon kicked more when hitched to a mobile, both on the day of the experiment and the day after. They had learned the link between a moving leg and a moving mobile. If, however, she hitched them to a different mobile the next day, the infants showed no learning. Their actions indicated that they remembered the original mobile and recognized the difference. Moreover, when tethered to the familiar mobile a month later, they remembered the association and again began kicking.

Traces of forgotten childhood languages may also persist. One study tested English-speaking British adults who had spoken Hindi (an Indian language) or Zulu (an African language) in their childhood. Although they had no conscious memory of those languages, they could, up to age 40, relearn subtle Hindi or Zulu sound contrasts that other people could not learn (Bowers et al., 2009). What the conscious mind does not know and cannot express in words, the nervous system and our two-track mind somehow remembers.

Cognitive Development

3-7 How did Piaget view the developmental stages of a child’s mind, and how does current thinking about cognitive development differ?

Cognition refers to all the mental activities associated with thinking, knowing, remembering, and communicating. Somewhere on your journey from egg-hood to childhood you became conscious. When was that, and how did your mind unfold from there? Psychologist Jean Piaget [Pee-ah-ZHAY] spent a half-century searching for answers to such questions. Thanks partly to his pioneering work, we now understand that a child’s mind is not a miniature model of an adult’s. Children reason differently, in “wildly illogical ways about problems whose solutions are self-evident to adults” (Brainerd, 1996).

Piaget’s interest began in 1920, when he was developing questions for children’s intelligence tests in Paris. Looking over the test results, Piaget noticed something interesting. At certain ages, children made strikingly similar mistakes. Where others saw childish mistakes, Piaget saw intelligence at work.

Piaget’s studies led him to believe that a child’s mind develops through a series of stages. This upward march begins with the newborn’s simple reflexes, and it ends with the adult’s abstract reasoning power. Moving through these stages, Piaget believed, is like climbing a ladder. A child can’t easily move to a higher rung without first having a firm footing on the one below.

Tools for thinking and reasoning differ in each stage. Thus, you can tell an 8-year-old that “getting an idea is like having a light turn on in your head,” and the child will understand. A 2-year-old won’t get the analogy. Would a 2-year-old understand that a miniature slide is too small for sliding, or that a miniature car is much too small to get into? (See FIGURE 3.8.) No. But an adult mind likewise can reason in ways that an 8-year-old won’t understand.

Piaget believed that the force driving us up this intellectual ladder is our struggle to make sense of our experiences. His core idea was that “children are active thinkers, constantly trying to construct more advanced understandings of the world” (Siegler & Ellis, 1996). Part of this active thinking is building schemas, which are concepts or mental molds into which we pour our experiences. By adulthood we have built countless schemas, ranging from what a dog is to what love is.

To explain how we use and adjust our schemas, Piaget proposed two more concepts. First, we assimilate new experiences—we interpret them in terms of our current understandings (schemas). Having a simple schema for dog, for example, a toddler may call all four-legged animals dogs. But as we interact with the world, we also adjust, or accommodate, our schemas to incorporate information provided by new experiences. Thus, the child soon learns that the original dog schema is too broad and accommodates by refining the category.

Piaget’s Theory and Current Thinking

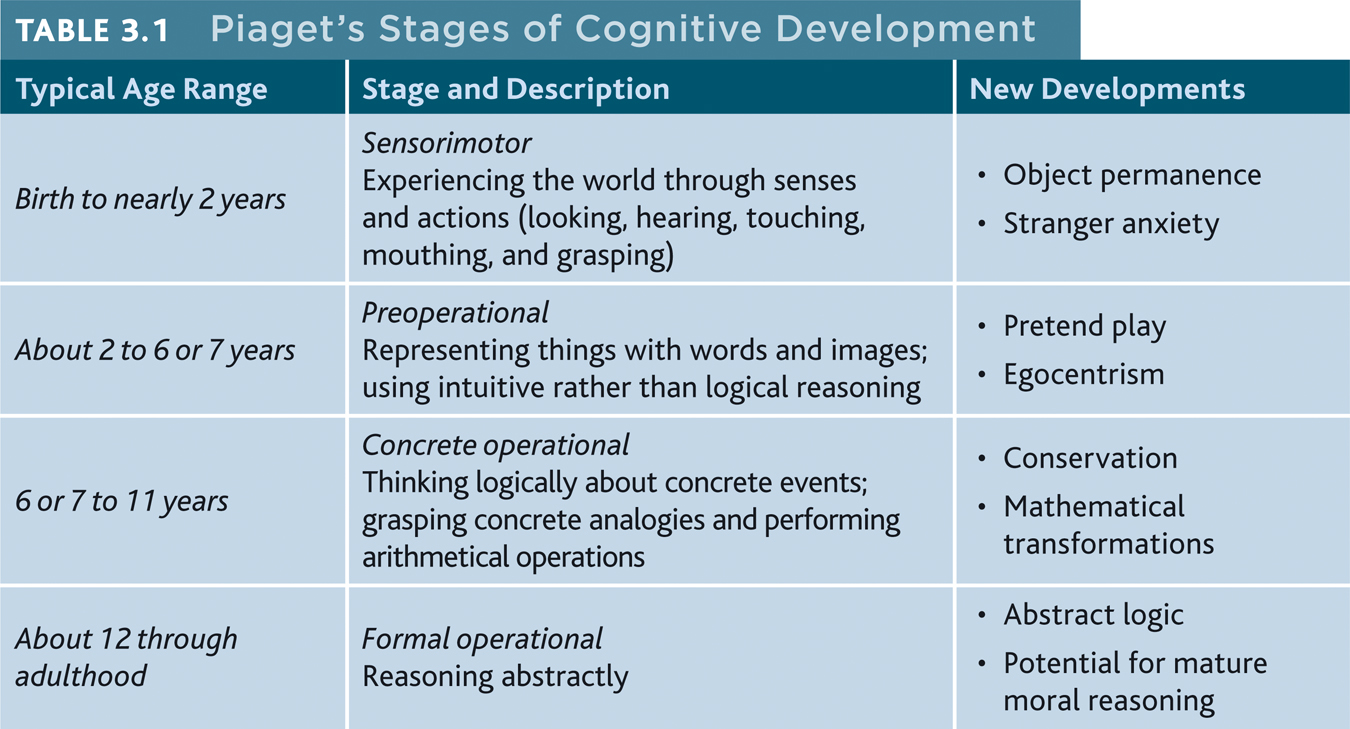

Piaget believed that children construct their understanding of the world as they interact with it. Their minds go through spurts of change, he believed, followed by greater stability as they move from one level to the next. In his view, cognitive development consisted of four major stages—sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operational, and formal operational.

SENSORIMOTOR STAGE The sensorimotor stage begins at birth and lasts to nearly age 2. In this stage, babies take in the world through their senses and actions—through looking, hearing, touching, mouthing, and grasping. As their hands and limbs begin to move, they learn to make things happen.

Very young babies seem to live in the present. Out of sight is out of mind. In one test, Piaget showed an infant an appealing toy and then flopped his hat over it. Before the age of 6 months, the infant acted as if the toy no longer existed. Young infants lack object permanence—the awareness that objects continue to exist when out of sight (FIGURE 3.9). By about 8 months, infants begin to show that they do remember things they can no longer see. If you hide a toy, an 8-month-old will briefly look for it. Within another month or two, the infant will look for it even after several seconds have passed.

So does object permanence in fact blossom at 8 months, much as tulips blossom in spring? Today’s researchers think not. They believe object permanence unfolds gradually, and they view development as more continuous than Piaget did.

They also think that young children are more competent than Piaget and his followers believed. For example, infants seem to have an inborn grasp of simple physical laws—they have “baby physics.” Like adults staring in disbelief at a magic trick (the “Whoa!” look), infants look longer at an unexpected and unfamiliar scene of a car seeming to pass through a solid object. They also stare longer at a ball stopping in midair, or at an object that seems to magically disappear (Baillargeon, 1995, 2008; Wellman & Gelman, 1992). Even as babies, we had a lot on our minds.

PREOPERATIONAL STAGE Piaget believed that until about age 6 or 7, children are in a preoperational stage—too young to perform mental operations (such as imagining an action and mentally reversing it).

Conservation Consider a 5-year-old, who objects that there is too much milk in a tall, narrow glass. “Too much” may become an acceptable amount if you pour that milk into a short, wide glass. Focusing only on the height dimension, the child cannot perform the operation of mentally pouring the milk back into the tall glass. Before about age 6, said Piaget, young children lack the concept of conservation—the idea that the amount remains the same even if it changes shape (FIGURE 3.10).

Pretend Play A child who can perform mental operations can think in symbols and therefore begins to enjoy pretend play. Contemporary researchers have found symbolic thinking at an earlier age than Piaget supposed. One researcher showed children a model of a room and hid a miniature stuffed dog behind its miniature couch (DeLoache & Brown, 1987). The 2½-year-olds easily remembered where to find the miniature toy in the model, but that knowledge didn’t transfer to the real world. They could not use the model to locate an actual stuffed dog behind a couch in a real room. Three-year-olds—only 6 months older—usually went right to the actual stuffed animal in the real room, showing they could think of the model as a symbol for the room. Piaget did not view the change from one stage to another as an abrupt shift. Even so, he probably would have been surprised to see symbolic thinking at such a young age.

Egocentrism Piaget also believed that preschool children are egocentric: They have difficulty imagining things from another’s point of view. Asked to “show Mommy your picture,” 2-year-old Gabriella holds the picture up facing her own eyes. Told to hide, 3-year-old Gray puts his hands over his eyes, assuming that if he can’t see you, you can’t see him.

Contemporary research supports preschoolers’ egocentrism. This is helpful information when a TV-watching preschooler blocks your view of the screen. The child probably assumes that you see what she sees. At this age, children simply are not yet able to take another’s viewpoint. Even we adults may overestimate the extent to which others share our views. Have you ever mistakenly assumed that something would be clear to a friend because it was clear to you? Or sent a text mistakenly thinking that the receiver would “hear” your “just kidding” intent (Epley et al., 2004; Kruger et al., 2005)? As children, we were even more prone to such egocentricism.

Theory of Mind When Little Red Riding Hood realized her “grandmother” was really a wolf, she swiftly revised her ideas about the creature’s intentions and raced away. Preschoolers develop this ability to read others’ mental states when they begin forming a theory of mind.

When children can imagine another person’s viewpoint, all sorts of new skills emerge. They can tease, because they now understand what makes a playmate angry. They may be able to convince a sibling to share. Knowing what might make a parent buy a toy, they may try to persuade.

Between about 3½ and 4½, children worldwide use their new theory-of-mind skills to realize that others may hold false beliefs (Callaghan et al., 2005; Sabbagh et al., 2006). One research team asked preschoolers what was inside a Band-Aids box (Jenkins & Astington, 1996). Expecting Band-Aids, the children were surprised to see that the box contained pencils. Then came the theory-of-mind question. Asked what a child who had never seen the box would think was inside, 3-year-olds typically answered “pencils.” By age 4 to 5, children knew better. They anticipated their friends’ false belief that the box would hold Band-Aids.

Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have an impaired theory of mind (Rajendran & Mitchell, 2007; Senju et al., 2009). They have difficulty reading other people’s thoughts and feelings. Most children learn that another child’s pouting mouth signals sadness, and that twinkling eyes mean happiness or mischief. A child with ASD fails to understand these signals (Frith & Frith, 2001).

ASD has differing levels of severity. “High-functioning” individuals generally have normal intelligence, and they often have an exceptional skill or talent in a specific area. But they lack social and communication skills, and they tend to become distracted by minor and unimportant stimuli (Remington et al., 2009). Those at the spectrum’s lower end are unable to use language at all.

Biological factors, including genetic influences and abnormal brain development, contribute to ASD (State and Sestan, 2012). Childhood measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccinations do not (Demicheli et al., 2012). Based on a fraudulent 1998 study—“the most damaging medical hoax of the last 100 years” (Flaherty, 2011)—some parents were misled into thinking that the childhood MMR vaccine increased risk of ASD. The unfortunate result was a drop in vaccination rates and an increase in cases of measles and mumps. Some unvaccinated children suffered long-term harm or even death.

ASD afflicts four boys for every girl. Psychologist Simon Baron-Cohen believes this hints at another way to understand this disorder. He has argued that ASD represents an “extreme male brain” (2008, 2009). Although there is some overlap between the sexes, he believes that boys are better “systemizers.” They understand things according to rules or laws, for example, as in mathematical and mechanical systems. Children exposed to high levels of the male sex hormone testosterone in the womb may develop more masculine and ASD-related traits (Auyeung et al., 2009).

In contrast, girls are naturally predisposed to be “empathizers,” Baron-Cohen contends. They are better at reading facial expressions and gestures, though less so if given testosterone (van Honk et al., 2011). Why is reading faces such a challenging task for those with ASD? The underlying cause seems to be poor communication among brain regions that normally work together to let us take another’s viewpoint. This effect appears to result from ASD-related genes interacting with the environment (State & Šestan, 2012).

CONCRETE OPERATIONAL STAGE By age 6 or 7, said Piaget, children enter the concrete operational stage. Given concrete (physical) materials, they begin to grasp conservation. Understanding that change in form does not mean change in quantity, they can mentally pour milk back and forth between glasses of different shapes. They also enjoy jokes that allow them to use this new understanding:

Mr. Jones went into a restaurant and ordered a whole pizza for his dinner. When the waiter asked if he wanted it cut into 6 or 8 pieces, Mr. Jones said, “Oh, you’d better make it 6, I could never eat 8 pieces!” (McGhee, 1976)

Piaget believed that during the concrete operational stage, children become able to understand simple math and conservation. When my daughter, Laura, was 6, I was astonished at her inability to reverse simple arithmetic. Asked, “What is 8 plus 4?” she required 5 seconds to compute “12,” and another 5 seconds to then compute 12 minus 4. By age 8, she could answer a reversed question instantly.

FORMAL OPERATIONAL STAGE By age 12, said Piaget, our reasoning expands to include abstract thinking. We are no longer limited to purely concrete reasoning, based on actual experience. As children approach adolescence, many become capable of abstract if…then thinking: If this happens, then that will happen. Piaget called this new systematic reasoning ability formal operational thinking. (Stay tuned for more about adolescents’ thinking abilities later in this chapter.) TABLE 3.1 summarizes the four stages in Piaget’s theory.

An Alternative Viewpoint: Vygotsky and the Social Child

As Piaget was forming his theory of cognitive development, Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky was also studying how children think and learn. He noted that by age 7, children are more able to think and solve problems with words. They do this, he said, by no longer thinking aloud. Instead they internalize their culture’s language and rely on inner speech (Fernyhough, 2008). Parents who say “No, no!” when pulling a child’s hand away from a cake are giving the child a self-control tool. When the child later needs to resist temptation, he may likewise think “No, no!” Talking to themselves, whether out loud or inside their heads, helps children to control their behavior and emotions and to master new skills.

Piaget emphasized how the child’s mind grows through interaction with the physical environment. Vygotsky emphasized how the child’s mind grows through interaction with the social environment. If Piaget’s child was a young scientist, Vygotsky’s was a young apprentice. By guiding children and giving them new words, parents and others provide a temporary scaffold from which children can step to higher levels of thinking (Renninger & Granott, 2005). Language is an important ingredient of social guidance, and it provides the building blocks for thinking, noted Vygotsky. (For more on children’s development of language, see Chapter 8.)

Reflecting on Piaget’s Theory

What remains of Piaget’s ideas about the child’s mind? Plenty. Time magazine singled him out as one of the twentieth century’s 20 most influential scientists and thinkers. And a survey of British psychologists rated him as the greatest twentieth-century psychologist (Psychologist, 2003). Piaget identified significant cognitive milestones and stimulated worldwide interest in how the mind develops. His emphasis was less on the ages at which children typically reach specific milestones than on their sequence. Studies around the globe, from Algeria to North America, have confirmed that human cognition unfolds basically in the sequence Piaget described (Lourenco & Machado, 1996; Segall et al., 1990).

However, today’s researchers see development as more continuous than did Piaget. By detecting the beginnings of each type of thinking at earlier ages, they have revealed conceptual abilities Piaget missed. Moreover, they view formal logic as a smaller part of cognition than he did. Piaget would not be surprised that today, as part of our own cognitive development, we are adapting his ideas to accommodate new findings.

Piaget’s insights can nevertheless help teachers and parents understand young children. Remember this: Young children cannot think with adult logic and cannot take another’s viewpoint. What seems simple and obvious to us—getting off a teeter-totter will cause a friend on the other end to crash—may never occur to a 3-year-old. Also remember that children are not empty containers waiting to be filled with knowledge. By building on what children already know, we can engage them in concrete demonstrations and stimulate them to think for themselves. Finally, accept children’s cognitive immaturity as adaptive. It is nature’s strategy for keeping children close to protective adults and providing time for learning and socialization (Bjorklund & Green, 1992).

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 3.3

Object permanence, pretend play, conservation, and abstract logic are developmental milestones for which of Piaget’s stages, respectively?

Object permanence, pretend play, conservation, and abstract logic are developmental milestones for which of Piaget’s stages, respectively?

Object permanence for the sensorimotor stage, pretend play for the preoperational stage, conservation for the concrete operational stage, and abstract logic for the formal operational stage.

Question 3.4

Match each developmental ability (1–6) to the correct cognitive developmental stage (a–d).

Match each developmental ability (1–6) to the correct cognitive developmental stage (a–d).

|

|

1. d, 2. b, 3. c, 4. c, 5. a, 6. b

Social Development

From birth, babies all over the world are social creatures, developing an intense bond with their caregivers. Infants come to prefer familiar faces and voices, then to coo and gurgle when given their mother’s or father’s attention. Have you ever wondered why tiny infants can happily be handed off to admiring visitors, but after a certain age pull back? By about 8 months, soon after object permanence emerges and children become mobile, a curious thing happens: They develop stranger anxiety. When handed to a stranger they may cry and reach for a parent. “No! Don’t leave me!” their distress seems to say. At about this age, children have schemas for familiar faces—mental images of how caretakers should look. When the new face does not fit one of these remembered images, they become distressed (Kagan, 1984). Once again, we see an important principle: The brain, mind, and social-emotional behavior develop together.

Origins of Attachment

3-8 How do the bonds of attachment form between caregivers and infants?

One-year-olds typically cling tightly to a parent when they are frightened or expect separation. Reunited after being apart, they shower the parent with smiles and hugs. No social behavior is more striking than this intense and mutual infant-parent bond. This attachment bond is a powerful survival impulse that keeps infants close to their caregivers.

DigitalVues/Alamy

Infants become attached to people—typically their parents—who are comfortable and familiar. For many years, psychologists reasoned that infants grew attached to those who satisfied their need for nourishment. It made sense. But an accidental finding overturned this idea.

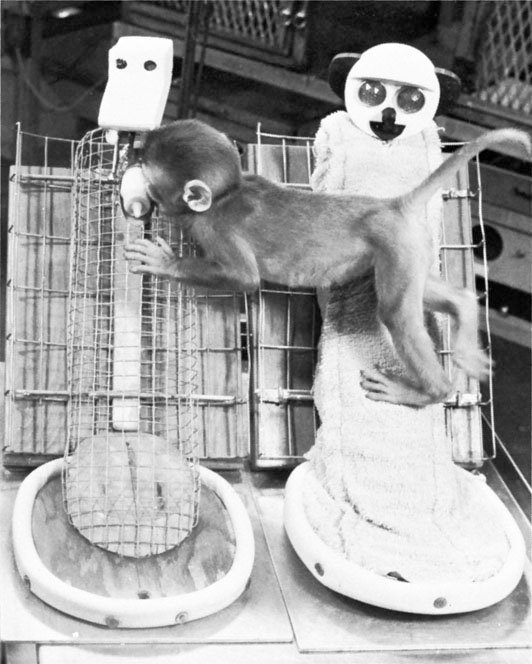

During the 1950s, University of Wisconsin psychologists Harry Harlow and Margaret Harlow bred monkeys for their learning studies. Shortly after birth, they separated the infants from their mothers and placed each infant in a sanitary individual cage with a cheesecloth baby blanket (Harlow et al., 1971). Then came a surprise: When their soft blankets were taken to be laundered, the infant monkeys became distressed.

Imagine yourself as one of the Harlows, trying to figure out why the monkey infants were so intensely attached to their blankets. Psychologists believed that infants became attached to those who nourish them. Might comfort instead be the key? How could you test that idea? The Harlows decided to pit the drawing power of a food source against the contact comfort of the blanket by creating two artificial mothers. One was a bare wire cylinder with a wooden head and an attached feeding bottle. The other was a cylinder wrapped with terry cloth.

For the monkeys, it was no contest. They overwhelmingly preferred the comfy cloth mother (FIGURE 3.11). Like anxious infants clinging to their live mothers, the monkey babies would cling to their cloth mothers when anxious. When exploring their environment, they used her as a secure base. They acted as though they were attached to her by an invisible elastic band that stretched only so far before pulling them back. Researchers soon learned that other qualities—rocking, warmth, and feeding—made the cloth mother even more appealing.

Human infants, too, become attached to parents who are soft and warm and who rock, pat, and feed. Much parent-infant emotional communication occurs via touch (Hertenstein et al., 2006), which can be either soothing (snuggles) or arousing (tickles). The human parent also provides a safe haven for a distressed child and a secure base from which to explore.

Attachment Differences

3-9 Why do secure and insecure attachments matter, and how does an infant develop basic trust?

Children’s attachments differ. To study these differences, Mary Ainsworth (1979) designed the strange situation experiment. She observed mother-infant pairs at home during their first six months. Later she observed the 1-year-old infants in a strange situation (usually a laboratory playroom) without their mothers. Such research shows that about 60 percent of infants display secure attachment. In their mother’s presence, they play comfortably, happily exploring their new environment. When she leaves, they become upset. When she returns, they seek contact with her.

Other infants avoid attachment or show insecure attachment, marked by either anxiety or avoidance of trusting relationships. They are less likely to explore their surroundings. Anxiously attached infants may cling to their mother. When she leaves, they might cry loudly and remain upset. Avoidantly attached infants seem not to notice or care about her departure and return (Ainsworth, 1973, 1989; Kagan, 1995; van IJzendoorn & Kroonenberg, 1988).

Ainsworth and others found that sensitive, responsive mothers—those who noticed what their babies were doing and responded appropriately—had infants who were securely attached (De Wolff & van IJzendoorn, 1997). Insensitive, unresponsive mothers—mothers who attended to their babies when they felt like doing so but ignored them at other times—often had infants who were insecurely attached. The Harlows’ monkey studies, with unresponsive artificial mothers, produced even more striking effects. When put in strange situations without their artificial mothers, the deprived infants were terrified (FIGURE 3.12).

Today’s climate of greater respect for animal welfare would prevent primate studies like the Harlows’. Many now remember Harry Harlow especially as the researcher who tortured helpless monkeys. But others support the Harlows’ work. “Harry Harlow, whose name has [come to mean] cruel monkey experiments, actually helped put an end to cruel child-rearing practices,” said primatologist Frans de Waal (2011). Harry Harlow defended their methods: “Remember, for every mistreated monkey there exist a million untreated children.” He expressed the hope that this research would sensitize people to child abuse and neglect. His biographer agreed. “No one who knows [the Harlows’] work could ever argue that babies do fine without companionship, that a caring mother doesn’t matter. And since we…didn’t fully believe that before…, then perhaps we needed—just once—to be smacked really hard with that truth so that we could never again doubt” (Blum, 2010, pp. 292, 307).

So caring parents matter. But is attachment style the result of parenting? Or are other factors also at work?

TEMPERAMENT AND ATTACHMENT How does temperament—a person’s characteristic emotional reactivity and intensity—affect attachment style? As we saw earlier in this chapter, temperament is genetically influenced. Some babies tend to be difficult—irritable, intense, and unpredictable. Others are easy—cheerful, relaxed, and feeding and sleeping on predictable schedules (Chess & Thomas, 1987). Parenting studies that neglect such inborn differences, critics say, might as well be “comparing foxhounds reared in kennels with poodles reared in apartments” (Harris, 1998). To separate the effects of nature and nurture on attachment, we would need to vary parenting while controlling temperament. (Pause and think: If you were the researcher, how might you do this?)

One researcher’s solution was to randomly assign 100 temperamentally difficult infants to two groups. Half of the 6- to 9-month-olds were in the experimental group, in which mothers received personal training in sensitive responding. The other half were in a control group, in which mothers did not receive this training (van den Boom, 1990, 1995). At 12 months of age, 68 percent of the infants in the first group were rated securely attached, as were only 28 percent of the control group infants. Other studies support the idea that such programs can increase parental sensitivity and, to some extent, infant attachment security (Bakermans-Kranenburg et al., 2003; Van Zeijl et al., 2006).

Children’s anxiety over separation from parents peaks at around 13 months, then gradually declines (Kagan, 1976). This happens whether they live with one parent or two, are cared for at home or in a day-care center, live in North America, Guatamala, or the Kalahari Desert. As the power of early attachment relaxes, we humans begin to move out into a wider range of situations. We communicate with strangers more freely. And we stay attached emotionally to loved ones despite distance.

At all ages, we are social creatures. But as we mature, our secure base and safe haven shift—from parents to peers and partners (Cassidy & Shaver, 1999). We gain strength when someone offers, by words and actions, a safe haven: “I will be here. I am interested in you. Come what may, I will actively support you” (Crowell & Waters, 1994).

ATTACHMENT STYLES AND LATER RELATIONSHIPS Developmental theorist Erik Erikson (1902–1994), working with his wife, Joan Erikson, believed that securely attached children approach life with a sense of basic trust—a sense that the world is predictable and reliable. This lifelong attitude of trust rather than fear, they said, flows from children’s interactions with sensitive, loving caregivers.

Do our early attachments form the foundation for adult relationships, including our comfort with intimacy? Many researchers now believe they do (Birnbaum et al., 2006; Fraley et al., 2013). People who report that they had secure relationships with their parents tend to enjoy secure friendships (Gorrese & Ruggieri, 2012). Our adult styles of romantic love likewise exhibit either secure, trusting attachment; insecure, anxious attachment; or the avoidance of attachment (Feeney, 2008; Shaver & Mikulincer, 2007). Feeling insecurely attached to others during childhood, for example, may take two main forms in adulthood (Fraley et al., 2011). One is anxiety, in which people constantly crave acceptance but are overly alert to signs of possible rejection. The other is avoidance, in which people experience discomfort getting close to others and use avoidant strategies to maintain distance from others.

Deprivation of Attachment

If secure attachment fosters social trust, what happens when circumstances prevent a child from forming attachments? In all of psychology, there is no sadder research literature. Some of these babies were raised in institutions without a regular caregiver’s stimulation and attention. Others were locked away at home under conditions of abuse or extreme neglect. Most were withdrawn, frightened, even speechless. Those abandoned in Romanian orphanages during the 1980s looked “frighteningly like Harlow’s monkeys” (Carlson, 1995). The longer they were institutionalized, the more they bore lasting emotional scars (Chisholm, 1998; Nelson et al., 2009).

The Harlows’ monkeys bore similar scars if raised in total isolation, without even an artificial mother. As adults, when placed with other monkeys their age, they either cowered in fright or lashed out in aggression. When they reached sexual maturity, most were incapable of mating. Females who did have babies were often neglectful, abusive, even murderous toward them.

In humans, too, the unloved sometimes become the unloving. Some 30 percent of those who have been abused do later abuse their own children. This is four times the U.S. national rate of child abuse (Dumont et al., 2007; Widom, 1989a,b). Abuse victims have a doubled risk of later depression (Nanni et al., 2012). They are especially at risk for depression if they carry a gene variation that spurs stress-hormone production (Bradley et al., 2008). As we will see again and again, behavior and emotion arise from a particular environment interacting with particular genes.

Recall that, depending on our experience, genes may or may not be “expressed” (active), and that epigenetics studies how experience puts molecular marks on genes that influence their expression. Severe child abuse, for example, can affect the expression of genes (Labonté et al., 2012). Extreme childhood trauma can also leave footprints on the brain. Normally placid golden hamsters that are repeatedly threatened and attacked while young grow up to be cowards when caged with same-sized hamsters, or bullies when caged with weaker ones (Ferris, 1996). Young children who are terrorized through physical abuse or wartime atrocities (being beaten, witnessing torture, and living in constant fear) often suffer other lasting wounds. Many have reported nightmares, depression, and an adolescence troubled by substance abuse, binge eating, or aggression (Kendall-Tackett et al., 1993, 2004; Polusny & Follette, 1995; Trickett & McBride-Chang, 1995). So too with childhood sexual abuse. Especially if severe and prolonged, it places children at increased risk for health problems, psychological disorders, substance abuse, and criminality (Freyd et al., 2005; Tyler, 2002).

Still, many children successfully survive abuse. It’s true that most abusive parents—and many condemned murderers—were indeed abused. It’s also true that most children growing up in harsh conditions don’t become violent criminals or abusive parents. Indeed, hardship short of trauma often boosts mental toughness (Seery, 2011). When you face adversity, consider the silver lining. Your coping may strengthen your resilience—your ability to bounce back and go on to lead a better life.

Parenting Styles

3-10 What are three primary parenting styles, and what outcomes are associated with each?

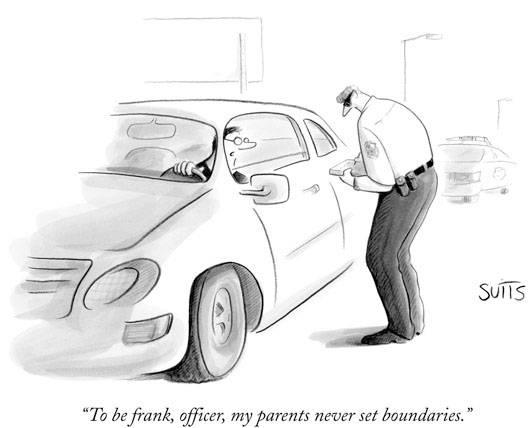

Child-raising practices vary. Some parents are strict, some are lax. Some show little affection, some liberally hug and kiss. Do parenting-style differences affect children?

The most heavily researched aspect of parenting has been how, and to what extent, parents seek to control their children. Investigators have identified three parenting styles:

- Authoritarian parents set the rules and expect obedience: “Don’t interrupt.” “Keep your room clean.” “Don’t stay out late or you’ll be grounded.” “Why? Because I said so.”

- Permissive parents give in to their children’s desires. They make few demands and use little punishment.

- Authoritative parents are both demanding and responsive. They exert control by setting rules, but especially with older children, they encourage open discussion and allow exceptions.

Too hard, too soft, and just right, these styles have been called. Studies reveal that children with authoritarian parents tend to have less social skill and self-esteem, and those with permissive parents tend to be more aggressive and immature. The children with the highest self-esteem, self-reliance, and social competence usually have warm, concerned, authoritative parents (Baumrind, 1996; Buri et al., 1988; Coopersmith, 1967). Two studies of thousands of Germans found that the parenting-competence link extended far into the future. Young adults whose parents had imposed a childhood curfew were better adjusted and had achieved more, compared with those who had permissive parents (Haase et al., 2008).

A word of caution: The association between certain parenting styles (being firm but open) and certain childhood outcomes (social competence) is correlational. Correlation is not causation. Perhaps you can imagine other possible explanations for this parenting-competence link.

Remember, too, that parenting doesn’t happen in a vacuum. One of the forces that influences parenting styles is culture.

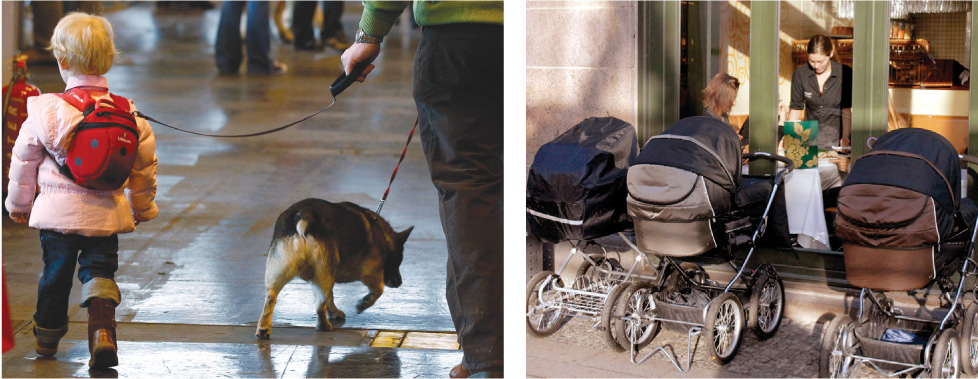

CULTURE AND CHILD RAISING Culture, as we noted in Chapter 1, is the set of enduring behaviors, ideas, attitudes, values, and traditions shared by a group of people and handed down from one generation to the next (Brislin, 1988). In Chapter 4, we’ll explore the effects of culture on gender. In later chapters we’ll consider the influence of culture on psychological disorders and social interactions. For now, let’s look at the way that child-raising practices reflect cultural values.

Cultural values vary from place to place and, even in the same place, from one time to another. Do you prefer children who are independent, or children who comply with what others think? The Westernized culture of the United States today favors independence. “You are responsible for yourself,” Western families and schools tell their children. “Follow your conscience. Be true to yourself. Discover your gifts. Think through your personal needs.” A half-century ago and more, however, Western cultural values placed greater priority on obedience, respect, and sensitivity to others (Alwin, 1990; Remley, 1988). “Be true to your traditions,” parents then taught their children. “Be loyal to your heritage and country. Show respect toward your parents and other superiors.” Cultures can change.

Francis Dean/Dean Pictures/The Image Works

Children across place and time have thrived under various child-raising systems. Upper-class British parents traditionally handed off routine caregiving to nannies, then sent their 10-year-olds away to boarding school. Many Americans now give children their own bedrooms and entrust them to day care.

Many Asian and African cultures place less value on independence and more on a strong sense of family self. They feel that what shames the child shames the family, and what brings honor to the family brings honor to the self. These cultures also value emotional closeness, and infants and toddlers may sleep with their mothers and spend their days close to a family member (Morelli et al., 1992; Whiting & Edwards, 1988). Sending children away would be shocking to an African Gusii family. Their babies nurse freely but spend most of the day on their mother’s back, with lots of body contact but little face-to-face and language interaction. If the mother becomes pregnant again, the toddler is weaned and handed over to another family member. Westerners may wonder about the negative effects of the lack of verbal interaction, but then the African Gusii may in turn wonder about Western mothers pushing their babies around in strollers and leaving them in playpens and car seats (Small, 1997). Such diversity in child raising cautions us against presuming that our culture’s way is the only way to raise children successfully.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 3.5

The three parenting styles have been called “too hard, too soft, and just right.” Which one is “too hard,” which one “too soft,” and which one “just right,” and why?

The three parenting styles have been called “too hard, too soft, and just right.” Which one is “too hard,” which one “too soft,” and which one “just right,” and why?

The authoritarian style would be too hard, the permissive style too soft, and the authoritative style just right. Parents using the authoritative style tend to have children with high self-esteem, self-reliance, and social competence.

Thinking About Nature and Nurture

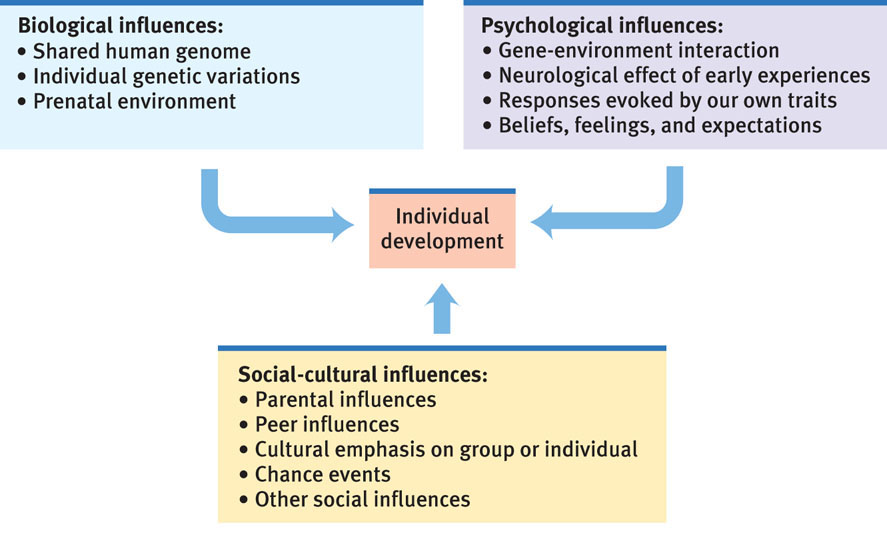

The unique gene combination created when our mother’s egg engulfed our father’s sperm helped form us as individuals. Genes predispose both our shared humanity and our individual differences.

But it also is true that our experiences form us. In the womb, in our families, and in our peer relationships, we learn ways of thinking and acting. Even differences initiated by our nature may be amplified by our nurture. We are not formed by either nature or nurture, but by the interaction between them. Biological, psychological, and social-cultural forces interact (FIGURE 3.13).

Mindful of how others differ from us, however, we often fail to notice the similarities stemming from our shared biology. Regardless of our culture, we humans share the same life cycle. We speak to our infants in similar ways and respond similarly to their coos and cries (Bornstein et al., 1992a,b). All over the world, the children of warm and supportive parents feel better about themselves and are less hostile than are the children of punishing and rejecting parents (Rohner, 1986; Scott et al., 1991). Although Hispanic, Asian, Black, and White Americans differ in school achievement and delinquency, the differences are “no more than skin deep” (Rowe et al., 1994). To the extent that family structure, peer influences, and parental education predict behavior in one of these ethnic groups, they do so for the others as well. Compared with the person‑to‑person differences within groups, the differences between groups are small. We share a human nature.