Adulthood

The unfolding of people’s adult lives continues across the life span. Earlier in this chapter, we considered what we all share in life’s early years. Making such statements about the adult years is much more difficult. If we know that James is a 1-year-old and Jamal is a 10-year-old, we can say a great deal about each child. Not so with adults who differ by a decade. A 20-year-old may be a parent who supports a child or a child who gets an allowance. A new mother may be 25 or 45. A boss may be 30 or 60.

Nevertheless, our life courses are in some ways similar. Physically, cognitively, and especially socially, we differ at age 60 from our 25-year-old selves. In the discussion that follows, we recognize these differences and use three terms: early adulthood (roughly twenties and thirties), middle adulthood (to age 65), and late adulthood (the years after 65). Remember, though, that within each of these stages, people vary widely in physical, psychological, and social development.

Physical Development

3-17 How do our bodies and sensory abilities change from early to late adulthood?

Early Adulthood

Our physical abilities—our muscular strength, reaction time, sensory keenness, and cardiac output—all crest by our mid-twenties. Like the declining daylight at the end of summer, the pace of our physical decline is a slow creep. Athletes are often the first to notice. World-class sprinters and swimmers peak by their early twenties. Women, who mature earlier than men, also peak earlier. But few of us notice. Unless our daily lives require us to be in top physical condition, we hardly perceive the early signs of decline.

Middle Adulthood

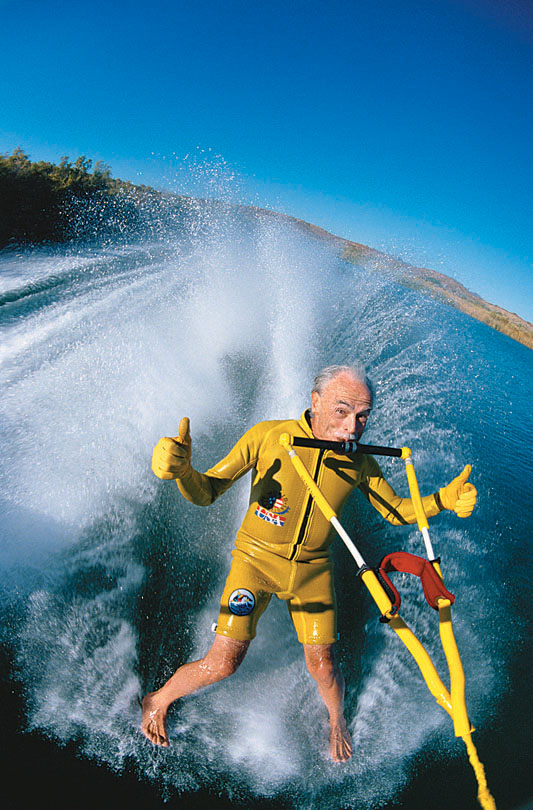

During early and middle adulthood, physical vigor has less to do with age than with a person’s health and exercise habits. Many of today’s sedentary 25-year-olds find themselves huffing and puffing up two flights of stairs. When they make it to the top and glance out the window, they may see their physically fit 50-year-old neighbor jog by on a daily 4-mile run.

Physical decline is gradual, but as most athletes know, the pace of that decline gradually picks up. As a lifelong basketball player, I find myself increasingly not racing for that loose ball. The good news is that even diminished vigor is enough for normal activities.

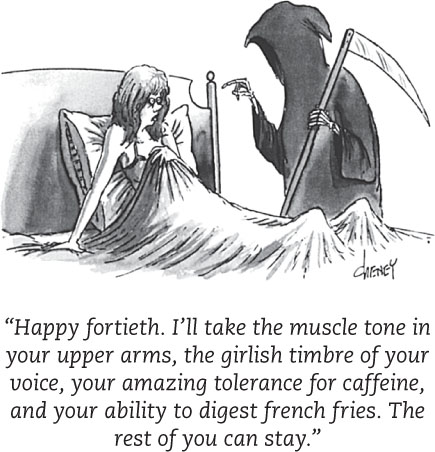

Aging also brings a gradual decline in fertility. For a 35- to 39-year-old woman, the chances of getting pregnant after a single act of intercourse are only half those of a woman 19 to 26 (Dunson et al., 2002). Women experience menopause, the end of the menstrual cycle, usually within a few years of age 50. Does she see this as a sign that she is losing her femininity and growing old? Or does she view it as liberation from menstrual periods and fears of pregnancy? The answer depends on her expectations and attitudes.

There is no male menopause—no end of fertility or sharp drop in sex hormones. Men experience a more gradual decline in sperm count, testosterone level, and speed of erection and ejaculation.

Late Adulthood

Is old age “more to be feared than death” (Juvenal, Satires)? Or is life “most delightful when it is on the downward slope” (Seneca, Epistulae ad Lucilium)? What is it like to grow old?

Although physical decline begins in early adulthood, we are not usually acutely aware of it until later life. Vision changes. We have trouble seeing fine details, and our eyes take longer to adapt to changes in light levels. As the eye’s pupil shrinks and its lens grows cloudy, less light reaches the retina—the light-sensitive inner portion of the eye. In fact, a 65-year-old retina receives only about one-third as much light as its 20-year-old counterpart (Kline & Schieber, 1985). Thus, to see as well as a 20-year-old when reading or driving, a 65-year-old needs three times as much light—a reason for buying cars with untinted windshields. This also explains why older people sometimes ask younger people, “Don’t you need better light for reading?”

Aging also levies a tax on the brain. The small, gradual net loss of brain cells begins in early adulthood. By age 80, the brain has lost about 5 percent of its former weight. This loss is a bit slower in women, who worldwide live an average 3.5 years longer than men (Salomon et al., 2012). But in both women and men, some of the brain regions that shrink during aging are the areas important for memory (Schacter, 1996). The frontal lobes, which help restrain impulsivity, also shrink, which helps explain older people’s occasional blunt comments and questions (“Have you put on weight?”) (von Hippel, 2007).

“I am still learning.”

Michelangelo, 1560, at age 85

Up to the teen years, we process information with greater and greater speed (Fry & Hale, 1996; Kail, 1991). But compared with teens and young adults, older people take a bit more time to react, to solve perceptual puzzles, even to remember names (Bashore et al., 1997; Verhaeghen & Salthouse, 1997). This neural processing lag is greatest on complex tasks (Cerella, 1985; Poon, 1987). At video games, most 70-year-olds are no match for a 20-year-old.

Some good news: As noted earlier, exercise slows aging. Fit bodies support fit minds. Physical exercise enhances muscles, bones, and energy and helps to prevent obesity and heart disease. It also stimulates brain cell development and neural connections, thanks perhaps to increased oxygen and nutrient flow (Erickson et al., 2010; Pereira et al., 2007). That may help explain why sedentary older adults randomly assigned to aerobic exercise programs exhibit enhanced memory, sharpened judgment, and reduced risk of neurocognitive disorder (formerly called “dementia”) (Colcombe et al., 2004; Liang et al., 2010; Nazimek, 2009). Exercise promotes neurogenesis (the birth of new nerve cells) in the hippocampus, a brain region important for memory.

File/AP Photo

Exercise also helps maintain the telomeres, which protect the ends of chromosomes (Cherkas et al., 2008; Erickson, 2009; Pereira et al., 2007). With age, telomeres wear down, much as the tip of a shoelace frays. Smoking, obesity, or stress can speed up this wear. As telomeres shorten, aging cells may die without being replaced with perfect genetic copies (Epel, 2009).

The message for seniors is clear: We are more likely to rust from disuse than to wear out from overuse.

Muscle strength, reaction time, and stamina also diminish noticeably in late adulthood. The fine-tuned senses of smell, hearing, and distance perception that we took for granted in our twenties and thirties will become distant memories. In later life, the stairs get steeper, the print gets smaller, and other people seem to mumble more.

Clever manufacturers have found a new market in this age-related difference in hearing. Some stores have reduced teen loitering by installing a device that emits a shrill, high-pitched sound that almost no one over 30 can hear (Barr, 2008; Lyall, 2005). Other teens have learned they can use that pitch to their advantage with cell-phone ringtones their instructors cannot hear (Vitello, 2006).

“For some reason, possibly to save ink, the restaurants had started printing their menus in letters the height of bacteria.”

Dave Barry, Dave Barry Turns Fifty, 1998

For those growing older, there is both bad and good news about health. The bad news: The body’s disease-fighting immune system weakens, putting older adults at higher risk for life-threatening ailments, such as cancer and pneumonia. The good news: Thanks partly to a lifetime’s collection of antibodies, those over 65 suffer fewer short-term ailments, such as common flu and cold viruses. One study found they were half as likely as 20-year-olds and one-fifth as likely as preschoolers to suffer upper respiratory flu each year (National Center for Health Statistics, 1990). No wonder older workers have lower absenteeism rates (Rhodes, 1983).

“The things that stop you having sex with age are exactly the same as those that stop you riding a bicycle (bad health, thinking it looks silly, no bicycle).”

Alex Comfort, The Joy of Sex, 2002

For both men and women, sexual activity also remains satisfying after middle age. When does sexual desire diminish? In one sexuality survey, age 75 was the point when most women and nearly half the men reported little sexual desire (DeLamater, 2012; DeLamater & Sill, 2005). In another study, 75 percent of those surveyed nevertheless reported being sexually active into their eighties (Schick et al., 2010).

Cognitive Development

Aging and Memory

3-18 How does memory change with age?

As we age, we remember some things well. Looking back in later life, people asked to recall the one or two most important events over the last half--century tend to name events from their teens or twenties (Conway et al., 2005; Rubin et al., 1998). Whatever people experienced around this time of life—World War II, the civil rights movement, the Vietnam war, or the Iraq war—gets remembered (Pillemer, 1998; Schuman & Scott, 1989). Our teens and twenties are also the time when we experience many of our big “firsts”—first date, first job, first day at college, first meeting with parents-in-law.

If you are within five years of 20, what experiences from your last year will you likely never forget? (When you are 70, this is the time of your life you may best remember.)

Early adulthood is indeed a peak time for some types of learning and remembering. Consider one experiment in which 1205 people were invited to learn some names (Crook & West, 1990). They watched video clips in which 14 strangers said their names, using a common format: “Hi, I’m Larry.” Then those strangers reappeared and gave additional details. For example, they said “I’m from Philadelphia,” which gave viewers more visual and voice cues for remembering the person’s name. After a second and third replay of the introductions, everyone remembered more names, but younger adults were consistently better than older adults.

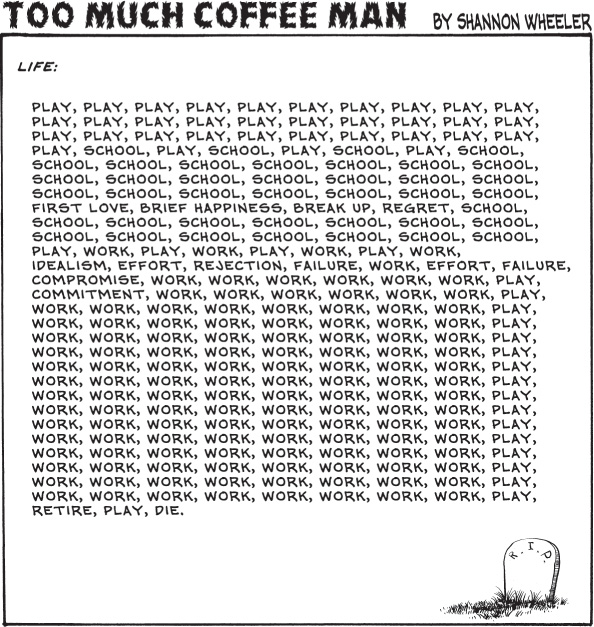

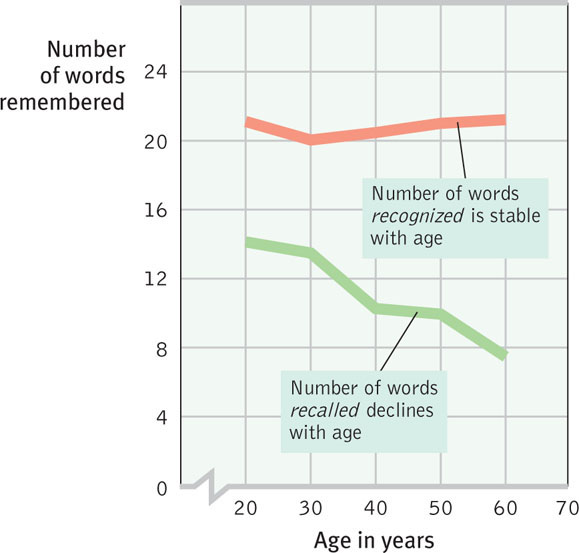

Perhaps it is not surprising, then, that nearly two-thirds of people over age 40 say their memory is worse than it was 10 years ago (KRC, 2001). In fact, how well older people remember depends on the task. When asked to recognize words they had earlier tried to memorize, people showed only a slight decline in memory. When asked to recall that information without clues, the decline was greater (FIGURE 3.16).

No matter how quick or slow we are, remembering seems also to depend on the type of information we are trying to retrieve. If the information is meaningless—nonsense syllables or unimportant events—then the older we are, the more errors we make. If the information is meaningful, older people’s rich web of existing knowledge will help them to hold it. But they may take longer than younger adults to produce the words and things they know: Quick-thinking game show winners are usually young or middle-aged adults (Burke & Shafto, 2004).

Chapter 8 explores another dimension of cognitive development: intelligence. As we will see, cross-sectional studies (comparing people of different ages) and longitudinal studies (restudying the same people over time) have identified mental abilities that do and do not change as people age. Age is less a predictor of memory and intelligence than is the nearness of death. Tell me whether someone is 8 months or 8 years from death and, regardless of age, you’ve given me a clue to that person’s mental ability. Especially in the last three or four years of life, the rate of cognitive decline typically increases (Wilson et al., 2007). Researchers call this near-death drop terminal decline (Backman & MacDonald, 2006).

Sustaining Mental Abilities

Recently, psychologists who study the aging mind have been debating whether “brain-fitness” computer-training programs can build “mental muscles” and hold off cognitive decline. Given what we know about the brain’s plasticity, can exercising our brains—with memory, visual tracking speed, and problem-solving exercises—prevent us from losing our minds? “At every point in life, the brain’s natural plasticity gives us the ability to improve how our brains function,” says one neuroscientist-entrepreneur (Merzenich, 2007). One study of nearly 3000 people found that 10 cognitive training sessions, with follow-up booster sessions, led to improved cognitive scores on tests related to their training (Boron et al., 2007; Willis et al., 2006).

Based on such findings, some computer-game makers are marketing daily brain-exercise programs for older people. But a veteran researcher of cognitive aging advises caution (Salthouse, 2010). The available evidence, he argues, does not indicate that the benefits of brain-mind exercise programs generalize to other tasks. A British study of 11,430 people who either completed one of two sets of brain-training activities over six weeks, or instead completed a control task, confirms the limited benefits. Although the training improved the practiced skills, it did not boost overall cognitive fitness (Owens et al., 2010). More encouraging results come from an impressive body of experiments showing that mental abilities gain a boost from aerobic exercise (Hertzog et al., 2008).

Social Development

3-19 What are adulthood’s two primary commitments, and how do chance events and the social clock influence us?

Adulthood’s Commitments

Two basic aspects of our lives dominate adulthood. Erik Erikson called them intimacy (forming close relationships) and generativity (being productive and supporting future generations). Sigmund Freud (1935) put it most simply: The healthy adult, he said, is one who can love and work.

LOVE We typically flirt, fall in love, and commit—one person at a time. “Pair-bonding is a trademark of the human animal,” observed anthropologist Helen Fisher (1993). From an evolutionary perspective, this pairing makes sense. Parents who cooperated to nurture their children to maturity were more likely to have their gene-carrying children survive and reproduce.

Romantic attraction is often influenced by chance encounters (Bandura, 1982). Psychologist Albert Bandura (2005) recalled the true story of a book editor who came to one of Bandura’s lectures on the “Psychology of Chance Encounters and Life Paths”—and ended up marrying the woman who happened to sit next to him.

Consider one study of identical twins and their spouses. Twins, especially identical twins, make similar choices of friends, clothes, vacations, jobs, and so on. So, if your identical twin became engaged to someone, wouldn’t you (being in so many ways the same as your twin) expect to also feel attracted to this person? Surprisingly, only half the identical twins recalled really liking their co-twin’s selection, and only 5 percent said, “I could have fallen for my twin’s partner.” This finding fits one explanation of romantic love: Given repeated exposure to someone after childhood, you may become attached to almost any available person who has a roughly similar background and level of attractiveness and who returns your affections (Lykken & Tellegen, 1993).

Bonds of love are most satisfying and enduring when two adults share similar interests and values and offer mutual emotional and material support. One of the ties that binds couples is self-disclosure—revealing intimate aspects of oneself to others (see Chapter 12).

The chances that a marriage will last also increase when couples marry after age 20 and are well educated. Shouldn’t this mean that fewer marriages would end in divorce today? Compared with their counterparts of 60 years ago, people in Western countries are better educated and marrying later. But in fact, they are nearly twice as likely to divorce today. (Both Canada and the United States now have about one divorce for every two marriages. In Europe, divorce is only slightly less common.) The divorce rate partly reflects women’s increased ability to support themselves, but it also reflects other changes. Both men and women now expect more than an enduring bond when they marry. Most hope for a mate who is a wage earner, caregiver, intimate friend, and warm and responsive lover.

Might test-driving life together in a “trial marriage” reduce divorce risk? In one Gallup survey of American twenty-somethings, 62 percent thought it would (Whitehead & Popenoe, 2001). In reality, in Europe, Canada, and the United States, those living together before marriage have had higher rates of divorce and marital troubles than those who have not lived together (Jose et al., 2010). The risk appears greatest for those who live together before becoming engaged (Goodwin et al., 2010; Rhoades et al., 2009). These couples tend to be initially less committed to the ideal of enduring marriage, and they become even less marriage-supporting while living together.

Nonetheless, the institution of marriage endures. Worldwide, reports the United Nations, 9 in 10 heterosexual adults marry. And marriage is a predictor of happiness, sexual satisfaction, income, and mental health (Scott et al., 2010). Neighborhoods with high marriage rates typically have low rates of crime, delinquency, and emotional disorders among children. Since 1972, surveys of nearly 50,000 Americans have revealed that 40 percent of married adults report being “very happy,” compared with 23 percent of unmarried adults. Lesbian couples, too, report greater well-being than those who are alone (Peplau & Fingerhut, 2007; Wayment & Peplau, 1995).

© Jose Luis Pelaez Inc/Blend Images/Corbis

Often, love bears children. For most people, this most enduring of life changes is a happy event. “I feel an overwhelming love for my children unlike anything I feel for anyone else,” said 93 percent of American mothers in a national survey (Erickson & Aird, 2005). Many fathers feel the same. A few weeks after the birth of my first child I was suddenly struck by a realization: “So this is how my parents felt about me!”

Children eventually leave home. This departure is a significant and sometimes difficult event. For most people, however, an empty nest is a happy place (Adelmann et al., 1989; Gorchoff et al., 2008). Many parents experience a “postlaunch honeymoon,” especially if they maintain close relationships with their children (White & Edwards, 1990). As Daniel Gilbert (2006) concluded, “The only known symptom of ‘empty nest syndrome’ is increased smiling.”

WORK Having work that fits your interests provides a sense of competence and accomplishment. For many adults, the answer to “Who are you?” depends a great deal on the answer to “What do you do?” Choosing a career path is difficult, especially during bad economic times. (See Appendix B: Psychology at Work for more on building work satisfaction.)

For both men and women, there exists a social clock—a culture’s definition of “the right time” to leave home, get a job, marry, have children, and retire. It’s the expectation people have in mind when saying “I married early” or “I started college late.” Today the clock still ticks, but people feel freer about keeping their own time.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 3.10

Freud defined the healthy adult as one who is able to ______ and to _____.

Freud defined the healthy adult as one who is able to ______ and to _____.

love; work

Well-Being Across the Life Span

3-20 What factors affect our well-being in later life?

To live is to grow older. This moment marks the oldest you have ever been and the youngest you will henceforth be. That means we all can look back with satisfaction or regret, and forward with hope or dread. When asked what they would have done differently if they could relive their lives, people most often answer, “Taken my education more seriously and worked harder at it” (Kinnier & Metha, 1989; Roese & Summerville, 2005). Other regrets—“I should have told my father I loved him,” “I regret that I never went to Europe”—have also focused less on mistakes made than on the things one failed to do (Gilovich & Medvec, 1995).

How will you look back on your life 10 years from now? Are you making choices that someday you will recollect with satisfaction?

From the teens to midlife, people’s sense of identity, confidence, and self-esteem typically grows stronger (Huang, 2010; Robins & Trzesniewski, 2005). In later life, challenges arise. Income often shrinks. Work is often taken away. The body declines. Recall fades. Energy wanes. Family members and friends die or move away. The great enemy, death, looms ever closer.

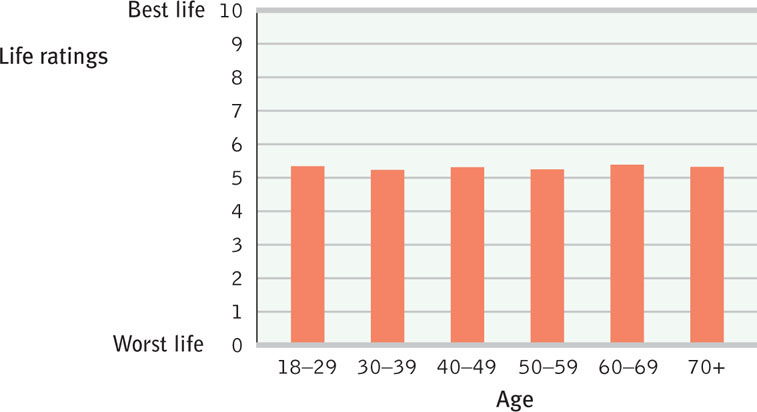

Small wonder that most believe that happiness declines in later life (Lacey et al., 2006; Lachman et al., 2008). Data collected from nearly 170,000 people in 16 nations show otherwise (Inglehart, 1990). People over 65 report as much happiness and satisfaction with life as younger people do (FIGURE 3.17).

“At 20 we worry about what others think of us. At 40 we don’t care what others think of us. At 60 we discover they haven’t been thinking about us at all.”

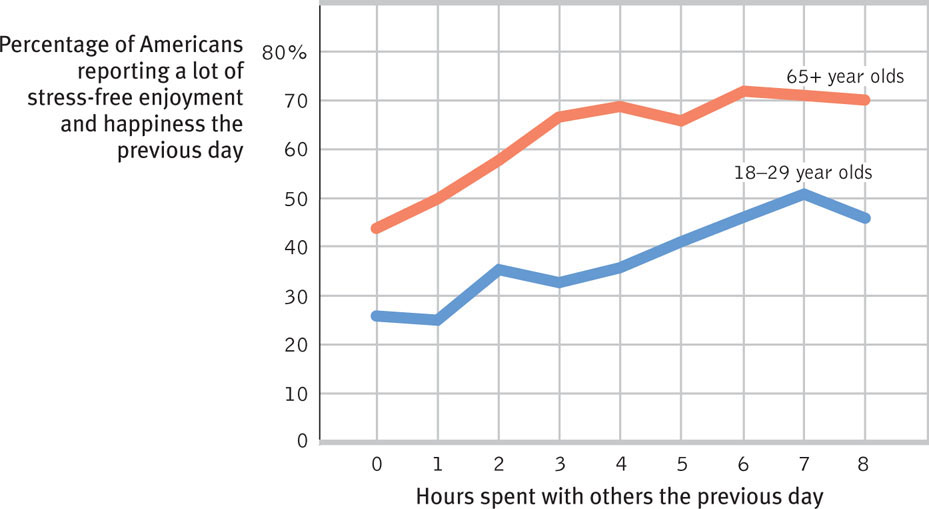

If anything, positive feelings, supported by better emotional control, grow after midlife, and negative feelings decline (Stone et al., 2010; Urry & Gross, 2010). Older adults increasingly express positive emotions (Pennebaker & Stone, 2003). Compared with younger adults, they pay more attention to positive news and are slower to perceive negative faces (Carstensen & Mikels, 2005; Scheibe & Carstensen, 2010). Older adults report less anger, stress, and worry, and have fewer problems in their social relationships (Fingerman & Charles, 2010). Like people of all ages, they are happiest when not alone (FIGURE 3.18).

Throughout the life span, the bad feelings tied to negative events fade faster than the good feelings linked with positive events (Walker et al., 2003). This contributes to most older people’s comforting sense that life, on balance, has been mostly good. As the years go by, feelings mellow (Costa et al., 1987; Diener et al., 1986). Highs become less high, lows less low.

Death and Dying

3-21 How do people vary in their responses to a loved one’s death?

Warning: If you begin reading the next paragraph, you will die.

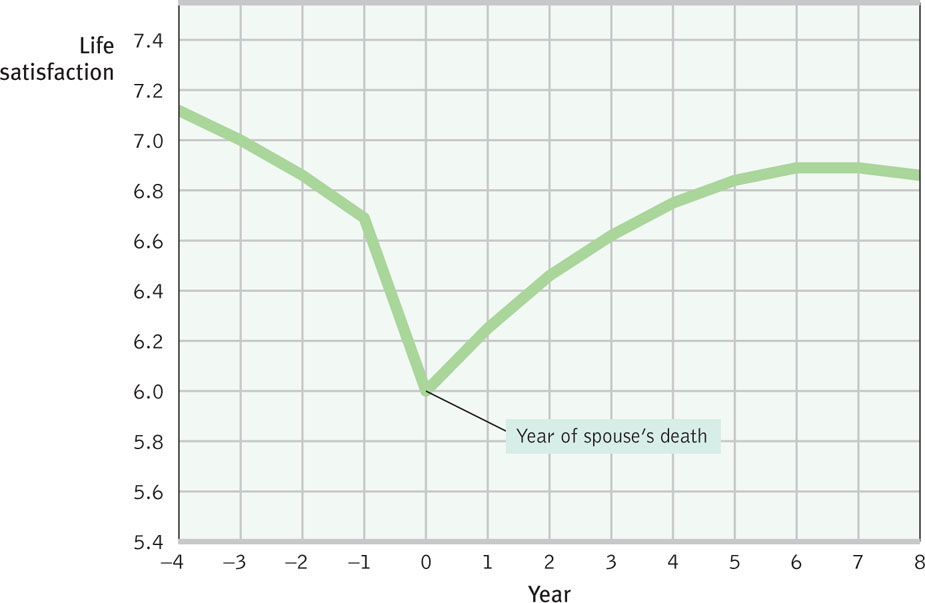

But of course, if you hadn’t read this, you would still die in due time. Death is our unavoidable end. Most of us will also have to suffer and cope with the death of a close relative or friend. Usually, the most difficult separation is from one’s spouse or partner—a loss suffered by five times more women than men. When, as usually happens, death comes at an expected late-life time—the “right time” on the social clock—the grieving usually passes. (FIGURE 3.19 shows the typical emotional path before and after a spouse’s death.)

Grief is especially severe when a loved one’s death comes suddenly and before its expected time. The sudden illness or accident that claims a 45-year-old life partner or a child may trigger a year or more of memory-filled mourning. Eventually, this may give way to a mild depression (Lehman et al., 1987).

For some, however, the loss is unbearable. One study tracked more than 17,000 people who had suffered the death of a child under 18. In the five years following that death, 3 percent of them were hospitalized for the first time in a psychiatric unit. This rate is 67 percent higher than the rate recorded for parents who had not lost a child (Li et al., 2005).

“Love—why, I’ll tell you what love is: It’s you at 75 and her at 71, each of you listening for the other’s step in the next room, each afraid that a sudden silence, a sudden cry, could mean a lifetime’s talk is over.”

Brian Moore, The Luck of Ginger Coffey, 1960

Why do grief reactions vary so widely? Some cultures encourage public weeping and wailing. Others expect mourners to hide their emotions. In all cultures, some individuals grieve more intensely and openly. Some popular beliefs, however, are not confirmed by scientific studies.

- Those who immediately express the strongest grief do not purge their grief faster (Bonanno & Kaltman, 1999; Wortman & Silver, 1989).

- Grief therapy and self-help groups offer support, but there is similar healing power in the passing of time, the support of friends, and the act of giving support and help to others (Baddeley & Singer, 2009; Brown et al., 2008; Neimeyer & Carrier, 2009). After a spouse’s death, those who talk often with others or who receive grief counseling adjust about as well as those who grieve more privately (Bonanno, 2009; Stroebe et al., 2005).

- Terminally ill and grief-stricken people do not go through identical stages, such as denial before anger (Friedman & James, 2008; Nolen-Hoeksema & Larson, 1999). Given similar losses, some people grieve hard and long, others grieve less (Ott et al., 2007).

We can be grateful for the waning of death-denying attitudes. Facing death with dignity and openness helps people complete the life cycle with a sense of life’s meaningfulness and unity—the sense that their existence has been good and that life and death are parts of an ongoing cycle. Although death may be unwelcome, life itself can be affirmed even at death. This is especially so for people who review their lives not with despair but with what Erik Erikson called a sense of integrity—a feeling that one’s life has been meaningful and worthwhile.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 3.11

What are some of the most significant challenges and rewards of growing old?

What are some of the most significant challenges and rewards of growing old?

Challenges: decline of muscular strength, reaction times, stamina, sensory keenness, cardiac output, and immune system functioning. Rewards: positive feelings tend to grow, negative emotions are less intense, and anger, stress, worry, and social-relationship problems decrease.

Thinking About Stability and Change

Photodisc/Getty Images

It’s time to address our third developmental issue. As we follow lives through time (in longitudinal studies), do we find more evidence for stability or change? If reunited with a long-lost grade-school friend, do we instantly realize that “it’s the same old Andy”? Or do people we befriend during one period of life seem like total strangers at a later period? (At least one man I know would choose the second option. He failed to recognize a former classmate at his 40-year college reunion. That upset classmate eventually pointed out that she was his long-ago first wife!)

Developmental psychologists’ research reveals that we experience both stability and change. Some of our characteristics, such as temperament, are very stable. As we noted earlier in this chapter, temperament seems to be something we’re born with. When a research team studied 1000 people from age 3 to 32, they were struck by the consistency of temperament and emotionality across time (Slutske et al., 2012). Out-of-control 3-year-olds were the most likely, at age 32, to be out-of-control gamblers. In other studies, 5-year-olds who demanded a lot of teacher attention tended to become 12-year-olds who still demanded a lot of teacher attention (Houts et al., 2010). And the widest smilers in childhood and college photos were, years later, the adults most likely to enjoy enduring marriages (Hertenstein et al., 2009).

We cannot, however, predict all of our eventual traits based on our early years (Kagan et al., 1978, 1998). Some traits, such as social attitudes, are much less stable than temperament, especially during the impressionable late adolescent years (Krosnick & Alwin, 1989; Moss & Susman, 1980). And older children and adolescents can learn new ways of coping. It is true that delinquent children later have high rates of work problems, substance abuse, and crime, but many confused and troubled children have blossomed into mature, successful adults (Moffitt et al., 2002; Roberts et al., 2001; Thomas & Chess, 1986). Happily for them, life is a process of becoming.

In some ways, we all change with age. Most shy, fearful toddlers begin opening up by age 4. In the years after adolescence, most people become more conscientious, self-disciplined, agreeable, and self-confident (Lucas & Donnellan, 2011; Roberts et al., 2003, 2006; Shaw et al., 2010). Conscientiousness increases especially during the twenties, and agreeableness during the thirties (Srivastava et al., 2003). Many a 20-year-old goof-off has matured into a 40-year-old business or cultural leader. (If you are the former, you aren’t done yet.) Such changes can occur without changing a person’s position relative to others of the same age. The hard-driving young adult may mellow by later life, yet still be a relatively hard-driving senior citizen.

Life requires both stability and change. Stability increasingly marks our personality as we age (Ferguson, 2010; Hopwood et al., 2011; Kandler et al., 2010). (“As at 7, so at 70,” says a Jewish proverb.) And stability gives us our identity. It lets us depend on others and be concerned about the healthy development of the children in our lives. Our trust in our ability to change gives us hope for a brighter future and lets us adapt and grow with experience.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 3.12

What findings in psychology support the idea of stability in personality across the life span? What findings challenge these ideas?

What findings in psychology support the idea of stability in personality across the life span? What findings challenge these ideas?

Some traits, such as temperament, do exhibit remarkable stability across many years. But we do change in other ways, such as in our social attitudes, especially during life’s early years.