Gender Development

We humans share an irresistible urge to organize our worlds into simple categories (Chapter 8). Among the ways we classify people—as tall or short, young or old, smart or dull—one stands out. Before or after your birth, everyone wanted to know, “Boy or girl?” The simple answer described your sex, your biological status, defined by your chromosomes and anatomy. For most people, those biological traits help define their gender, their culture’s expectations about what it means to be male or female. (You may recall from Chapter 1 that culture refers to everything that is shared by a group and transmitted across generations.)

We humans share an irresistible urge to organize our worlds into simple categories (Chapter 8). Among the ways we classify people—as tall or short, young or old, smart or dull—one stands out. Before or after your birth, everyone wanted to know, “Boy or girl?” The simple answer described your sex, your biological status, defined by your chromosomes and anatomy. For most people, those biological traits help define their gender, their culture’s expectations about what it means to be male or female. (You may recall from Chapter 1 that culture refers to everything that is shared by a group and transmitted across generations.)

Consider baby outfits. If you celebrate the birth of a boy with a gift of a pink outfit, his parents may frown at you. But in 1918, you probably would have received a big smile. “The generally accepted rule is pink for the boy and blue for the girl,” declared the publication Earnshaw’s Infants’ Department in June 1918 (Maglaty, 2011). “The reason is that pink being a more decided and stronger color is more suitable for the boy, while blue, which is more delicate and dainty, is prettier for the girls.” The way cultures define male and female varies, and it can change over time.

How Are We Alike? How Do We Differ?

4-1 What are some gender similarities and differences in aggression, social power, and social connectedness?

Whether male or female, each of us receives 23 chromosomes from our mother and 23 from our father. Of those 46 chromosomes, 45 are shared by men and women. Our similar biology helped our evolutionary ancestors face similar adaptive challenges. Both men and women needed to survive, reproduce, and avoid predators, and so today we are in most ways alike. Tell me whether you are male or female and you give me no clues to your vocabulary, happiness, or ability to see, hear, learn, and remember. Women and men, on average, are similarly creative and intelligent and feel the same emotions and longings. Our similarities as male and female cannot be overstressed. Our “opposite” sex is, in reality, our very similar sex.

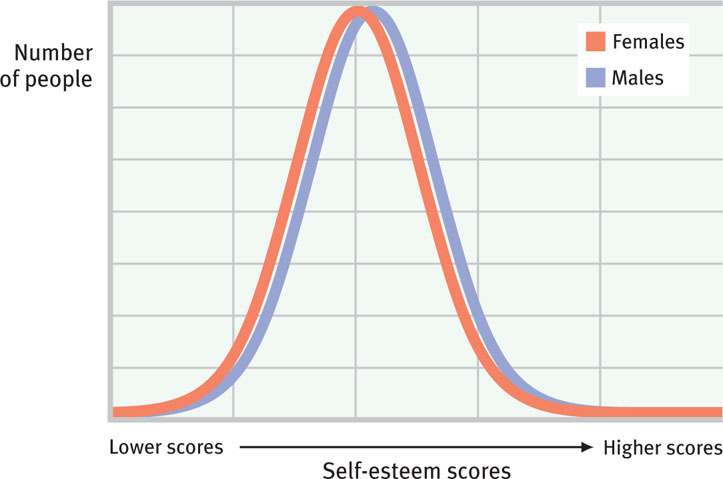

But in some areas, males and females do differ, and differences command attention. Some much talked-about gender differences (like the difference in self-esteem shown in FIGURE 4.1) are actually quite modest (Hyde, 2005). Other differences are more striking. The average woman enters puberty 2 years sooner than the average man, and her life span is 5 years longer. She carries 70 percent more fat, has 40 percent less muscle, and is 5 inches shorter. She expresses emotions more freely, can detect fainter odors, and receives offers of help more often. She also has twice the risk of developing depression and anxiety and 10 times the risk of developing an eating disorder. Yet the average man is 4 times more likely to die by suicide or to develop alcohol use disorder. His “more likely” list includes a childhood diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder, color-blindness, or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. And as an adult, he is more at risk for antisocial personality disorder. Each gender has its share of risks.

Gender differences are well studied, with 6500 related research articles appearing each year (Eagly et al., 2012). Let’s take a closer look at some differences in aggression, social power, and social connectedness.

Gender and Aggression

Are men more aggressive than women? Think of the most aggressive people you heard about last year. Were most of them men? Chances are good that they were. Men generally admit to more aggression. They also commit more extreme physical violence (Bushman & Huesmann, 2010). In romantic relationships between men and women, minor acts of physical aggression, such as slaps, are roughly equal, but extremely violent acts are mostly committed by men (Archer, 2000; Johnson, 2008).

Here’s another question: Think of stories about people harming others by passing along hurtful gossip, or by shutting someone out of a social group or situation. Were most of those people men? Perhaps not. Those behaviors are acts of relational aggression, and women are slightly more likely than men to commit them (Archer, 2004, 2006, 2009).

109

Laboratory experiments have demonstrated a gender gap in aggression. Men have been more willing to blast people with what they believed was intense and prolonged noise (Bushman et al., 2007). They have more readily zapped strangers with what they believed were intense electric shocks (Giancola, 2003). The gender gap also appears in real-life violent crime. Who commits more violent crimes worldwide? Men do (Antonaccio et al., 2011; Caddick & Porter, 2012; Frisell et al., 2012). Men also take the lead in hunting, fighting, warring, and supporting war (Wood & Eagly, 2002, 2007). More American men than American women, for example, consistently supported the Iraq war (Newport et al., 2007).

Gender and Social Power

Imagine walking into a job interview. You sit down and peer across the table at your two interviewers. The unsmiling person on the left oozes self-confidence and independence and maintains steady eye contact with you. The person on the right gives you a warm, welcoming smile but makes less eye contact and seems to expect the other interviewer to take the lead.

Which interviewer is male?

If you said the person on the left, you’re not alone. Around the world, from Nigeria to New Zealand, people have perceived gender differences in power (Williams & Best, 1990). Indeed, in most societies men do place more importance on power and achievement and are socially dominant (Schwartz & Rubel-Lifschitz, 2009).

- When groups form, whether as juries or companies, leadership tends to go to males (Colarelli et al., 2006).

- When salaries are paid, those in traditionally male occupations receive more.

- When people run for election, women who appear hungry for political power experience less success than their power-hungry male counterparts (Okimoto & Brescoll, 2010).

- When political leaders are elected, they usually are men, who held 80 percent of the seats in the world’s governing parliaments in 2011 (IPU, 2011).

Women’s 2011 representation in national parliaments ranged from 11 percent in the Arab States to 42 percent in Scandinavia (IPU, 2011).

Men and women also lead differently. Men tend to be more directive, telling people what they want and how to achieve it. Women tend to be more democratic, more welcoming of others’ input in decision making (Eagly & Carli, 2007; van Engen & Willemsen, 2004). When interacting, men are more likely to offer opinions, women to express support (Aries, 1987; Wood, 1987). In everyday behavior, men tend to act as powerful people often do: talking assertively, interrupting, initiating touches, and staring. And they smile and apologize less (Leaper & Ayres, 2007; Major et al., 1990; Schumann & Ross, 2010). Such behaviors help sustain men’s greater social power.

Gender and Social Connections

Whether male or female, we humans cherish social connections. We all have a need to belong (more on this in Chapter 9). But males and females satisfy this need in different ways (Baumeister, 2010). Males tend to be independent. Females tend to be more interdependent. This difference in social connectedness surfaces in children’s play. Boys typically form large groups. Their games tend to be active and competitive, with little intimate discussion (Rose & Rudolph, 2006). Girls usually play in small groups, often with one friend. They compete less and imitate social relationships more (Maccoby, 1990; Roberts, 1991).

© Ocean/Corbis

Gender differences in the way we interact continue in our adult years. Women’s social networks are larger than men’s (Igarsh et al., 2005). Women take more pleasure in talking face to face, and they more often use conversation to explore relationships. Men enjoy doing activities side by side and tend to use conversation to find solutions to problems (Tannen, 1990; Wright, 1989). Given these differences, perhaps it’s not surprising that the average U.S. teen girl sends and receives twice as many text messages as the average teen boy (Lenhart, 2010).

110

Worldwide, women’s interests and occupations reflect this focus on people rather than things (Eagly, 2009; Lippa, 2005, 2006, 2008). One study analyzed responses from more than half a million people. The results showed that “men prefer working with things and women prefer working with people” (Su et al., 2009). One of the things men seem to prefer working with is computers. American college men are seven times more likely than women to declare an interest in computer science (Pryor et al., 2011).

At home, women have been five times more likely than men to claim primary responsibility for taking care of children (Time, 2009). This may help explain why women in the workplace have been less driven by money and status and more often opted for reduced work hours (Pinker, 2008).

“In the long years liker must they grow; The man be more of woman, she of man.”

Alfred Lord Tennyson, The Princess, 1847

When searching for understanding from someone who will share their worries and hurts, people usually turn to women. Both men and women have reported their friendships with women to be more intimate, enjoyable, and nurturing (Rubin, 1985; Sapadin, 1988). In one study, 69 percent said they had a close relationship with their father, while 90 percent said they felt close to their mother (Hugick, 1989).

But how do they cope with their own stress? Compared with men, women are more likely to turn to others for support. They are said to tend and befriend (Tamres et al., 2002; Taylor, 2002).

Gender differences in both social connectedness and power peak in late adolescence and early adulthood—the prime years for dating and mating. Teenage girls become less assertive and more flirtatious, and boys appear more dominant and less expressive. Gender differences in attitudes and behavior often peak after the birth of a child. Mothers especially may become more traditional (Ferriman et al., 2009; Katz-Wise, 2010). By age 50, most parent-related gender differences subside. Men become less domineering and more empathic, and women—especially those with paid employment—become more assertive and self-confident (Kasen et al., 2006; Maccoby, 1998).

Is gender an either-or characteristic, or do we vary in the extent to which we are male or female? Does biology dictate gender? How much do our cultures and other experiences shape us? Read on.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 4.1

_________ (Men/Women) are more likely to commit relational aggression, and _________ (men/women) are more likely to commit physical aggression.

Women; men

Question 4.2

Worldwide, ________ (men/women) have tended to express more personal and professional interest in people and less interest in things.

women

The Nature of Gender: Our Biological Sex

4-2 How is our biological sex determined, and how do sex hormones influence prenatal and adolescent development?

Men and women use similar solutions when faced with challenges: sweating to cool down, guzzling an energy drink or coffee to get going in the morning, or finding darkness and quiet to sleep. When looking for a mate, men and women also prize many of the same traits. They prefer having a mate who is “kind,” “honest,” and “intelligent.” But according to evolutionary psychologists, in mating-related domains, males differ from females whether they’re chimpanzees or elephants, rural peasants or corporate presidents (Geary, 2010). Our biology may influence our gender differences in two ways: genetically, through our differing sex chromosomes, and physiologically, through our differing concentrations of sex hormones.

Our gender is a product of the interplay among our biological makeup, our developmental experiences, and our current situations (Eagly & Wood, 2013). Biology does not dictate gender, but it can influence it in two ways:

- Genetically—males and females have differing sex chromosomes.

- Physiologically—males and females have differing concentrations of sex hormones.

These two sets of influences began to form you long before you were born, when your tiny body started developing in ways that determined your sex.

Prenatal Sexual Development

Six weeks after you were conceived, you and someone of the other sex looked much the same. Then, as your genes kicked in, your biological sex became more apparent. Whether you are male or female, your mother’s contribution to your twenty‑third chromosome pair—the two sex chromosomes—was an X chromosome. It was your father’s contribution that determined your sex. From him, you received the one chromosome that is not unisex—either another X chromosome, making you a girl, or a Y chromosome, making you a boy.

111

Pubertal boys may not at first like their sparse beard. (But then it grows on them.)

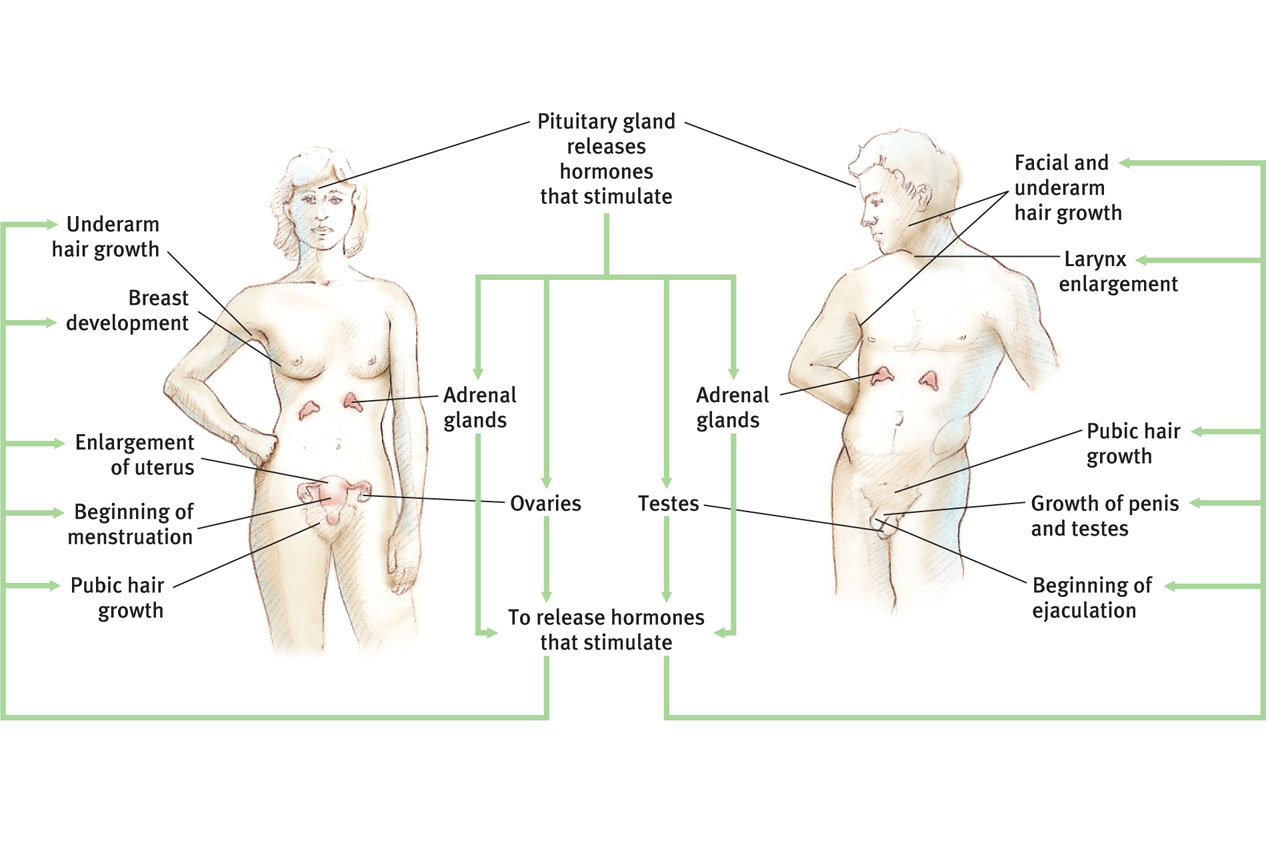

About seven weeks after conception, a single gene on the Y chromosome throws a master switch. “Turned on,” this switch triggers the testes to develop and to produce testosterone, the principal male hormone that promotes development of male sex organs. Females also have testosterone, but less of it. Later, during the fourth and fifth prenatal months, sex hormones will bathe the fetal brain and tilt its wiring toward female or male patterns (Hines, 2004; Udry, 2000).

Adolescent Sexual Development

During adolescence, boys and girls enter puberty and mature sexually. Pronounced physical differences emerge as a surge of hormones triggers a two-year period of rapid physical development. A variety of changes begin at about age 11 in girls and at about age 13 in boys. A year or two before that, boys and girls often feel the first stirrings of sexual attraction (McClintock & Herdt, 1996).

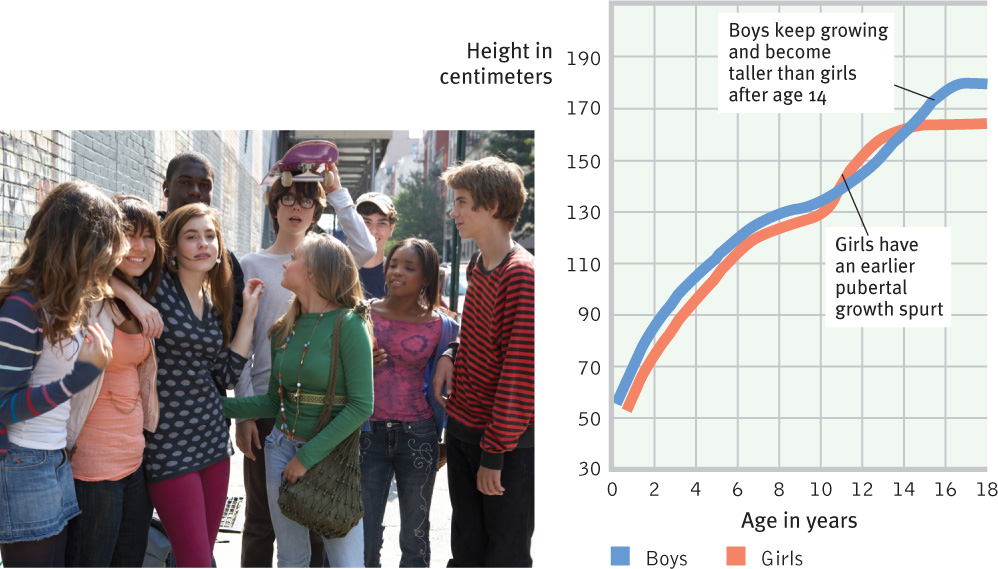

Girls’ slightly earlier entry into puberty can at first propel them to greater height than boys of the same age (FIGURE 4.2). But boys catch up when they begin puberty and by age 14 are usually taller than girls. During these growth spurts, the primary sex characteristics—the reproductive organs and external genitalia—develop dramatically. So do the secondary sex characteristics. Girls develop breasts and larger hips. Boys’ facial hair begins growing and their voices deepen. Pubic and underarm hair emerges in both girls and boys (FIGURE 4.3).

For boys, puberty’s landmark is the first ejaculation, which often occurs first during sleep (as a “wet dream”). This event, called spermarche (sper-MAR-key), usually happens by about age 14.

In girls, the landmark is the first menstrual period (menarche—meh-NAR-key), usually within a year of age 12½ (Anderson et al., 2003). Early menarche is more likely following stresses related to father absence, sexual abuse, insecure attachments, or a history of a mother’s smoking during pregnancy (Belsky et al., 2010; Shrestha et al., 2011; Vigil et al., 2005; Zabin et al., 2005). In various countries, girls are developing breasts earlier (sometimes before age 10) and reaching puberty earlier than in the past. Suspected triggers include increased body fat, more hormone-mimicking chemicals in their diet, and greater stress due to family disruption (Biro et al., 2010).

Girls who are prepared for menarche usually experience it positively (Chang et al., 2009). Most women recall their first menstrual period with mixed emotions—pride, excitement, embarrassment, and apprehension (Greif & Ulman, 1982; Woods et al., 1983). Men report mostly positive emotional reactions to spermarche (Fuller & Downs, 1990).

112

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 4.3

Adolescence is marked by the onset of ___________.

puberty

Variations on Sexual Development

Sometimes nature blurs the biological line between males and females. When a fetus is exposed to unusual levels of sex hormones or is especially sensitive to those hormones, the individual may develop characteristics of both sexes. These intersex individuals may be born with combinations of male and female physical features. A genetic male, for example, may have normal male hormones and testes but no penis or a very small one.

In the past, medical professionals often recommended surgery to create a female identity for these children. One study reviewed 14 cases of boys who had undergone early sex-reassignment surgery and had been raised as girls. Of those cases, 6 had later declared themselves male, 5 were living as females, and 3 reported an unclear gender identity (Reiner & Gearhart, 2004).

Sex-reassignment surgery can create confusion and distress among those not born with an intersex condition. In one famous case, a little boy lost his penis during a botched circumcision. His parents followed a psychiatrist’s advice to raise him as a girl rather than as a damaged boy. Alas, “Brenda” Reimer was not like most other girls. “She” didn’t like dolls. She tore her dresses with rough-and-tumble play. At puberty she wanted no part of kissing boys. Finally, Brenda’s parents explained what had happened, whereupon “Brenda” immediately rejected the assigned female identity. He cut his hair and chose a male name, David. He eventually married a woman and became a stepfather. And, sadly, he later committed suicide (Colapinto, 2000).

The bottom line: “Sex matters,” concluded the National Academy of Sciences (2001), insofar as sex-related genes and physiology “result in behavioral and cognitive differences between males and females.” Yet environmental factors matter too, as we will see next. Nature and nurture work together.

113

The Nurture of Gender: Our Culture and Experiences

4-3 How do gender roles and gender typing influence gender development?

In many cases, biological sex and gender exist together in harmony. Biology draws the outline, and culture provides the details.

Gender Roles

Cultures shape our behaviors by defining how we ought to behave in a particular social position, or role. We can see this shaping power in gender roles—the social expectations that guide our behavior as men or as women.

Gender roles shift over time and place. A century ago, North American women could not vote in national elections, serve in the military, or divorce a husband without cause. And if a woman worked for pay outside the home, she might have been a servant or a seamstress.

Gender roles can change dramatically in a thin slice of history. At the beginning of the twentieth century, only one country in the world—New Zealand—granted women the right to vote (Briscoe, 1997). Today, worldwide, only Saudi Arabia denies women the right to vote. Even there, the culture shows signs of shifting toward women’s voting rights (Alsharif, 2011). More U.S. women than men now graduate from college, and nearly half the U.S. workforce is female (Fry & Cohn, 2010). The modern economy has produced jobs that rely not on brute strength but on social intelligence, open communication, and the ability to sit still and focus (Rosin, 2010). What changes might the next hundred years bring?

Our gender roles are not everyone’s gender roles. In nomadic societies of food-gathering people, there is little division of labor by sex. Boys and girls receive much the same upbringing. In agricultural societies, where women work in the nearby fields and men roam while herding livestock, the culture has shaped children to assume more distinct gender roles (Segall et al., 1990; Van Leeuwen, 1978).

Take a minute to check your own gender expectations. Would you agree that “When jobs are scarce, men should have more rights to a job”? In the United States, Britain, and Spain, a little over 12 percent of adults agree. In Nigeria, Pakistan, and India, about 80 percent of adults agree (Pew, 2010). This question taps people’s views on the idea that men and women should be treated equally. We’re all human, but my, how our views differ. Australia and the Scandinavian countries offer the greatest gender equity, Middle Eastern and North African countries the least (Social Watch, 2006).

How Do We Learn to Be Male or Female?

A gender role describes how others expect us to act. Our gender identity is our personal sense of being male or female. How do we develop that personal viewpoint?

Social learning theory assumes that we acquire our gender identity in childhood, by observing and imitating others’ gender-linked behaviors and by being rewarded or punished for acting in certain ways. (“Tatiana, you’re such a good mommy to your dolls”; “Big boys don’t cry, Armand.”) Some critics think there’s more to gender identity than imitating parents and being repeatedly rewarded for certain behaviors. They ask us to consider how much gender typing—taking on the traditional male or female role—varies from child to child (Tobin et al., 2010). No matter how much parents encourage or discourage traditional gender behavior, children may drift toward what feels right to them. Some organize themselves into “boy worlds” and “girl worlds,” each guided by rules. Others seem to prefer androgyny: A blend of male and female roles feels right to them. Androgyny has benefits. Androgynous people are more adaptable. They show greater flexibility in behavior and career choices (Bem, 1993). They tend to be more resilient and self-accepting and experience less depression (Lam & McBride-Chang, 2007; Mosher & Danoff-Burg, 2008; Ward, 2000).

114

How you feel matters, but so does how you think. As you grew up, you formed schemas, or concepts that helped you make sense of your world. You use many of these schemas to think about your identity, about who you are. Your gender schema organizes your experiences of male-female characteristics (Bem, 1987, 1993; Martin et al., 2002).

Gender schemas form early in life. As a young child, you (like other children) were a “gender detective” (Martin & Ruble, 2004). Before your first birthday, you knew the difference between a male and female voice or face (Martin et al., 2002). After you turned 2, language forced you to label the world in terms of gender. English classifies people as he and she. Other languages classify objects as masculine (“le train”) or feminine (“la table”).

“The more I was treated as a woman, the more woman I became.”

Writer Jan Morris, male-to-female transsexual

Once children grasp that two sorts of people exist—and that they are of one sort—they search for clues about gender. Hints arise not only from language, but also from clothes, toys, books, shows, and games. Having divided the human world in half, 3-year-olds will then like their own kind better and seek them out for play. “Girls,” they may decide, are the ones who watch Dora the Explorer and have long hair. “Boys” watch battles from Kung Fu Panda and don’t wear dresses. Armed with their newly collected “proof,” they then adjust their behaviors to fit their concept of gender. These rigid stereotypes peak at about age 5 or 6. If the new neighbor is a boy, a 6-year-old girl may assume that she cannot share his interests. For young children, gender looms large.

Parents help to transmit their culture’s views on gender. In one analysis of 43 studies, parents with traditional gender schemas were more likely to have gender-typed children who shared their culture’s expectations about how males and females should act (Tenenbaum & Leaper, 2002). For transgender people, however, comparisons with their culture’s concept of gender produces feelings of confusion and discord. For transgender persons, gender identity (one’s sense of being male or female) or gender expression (behavior or appearance) differs from what’s typical for one’s birth sex (APA, 2010). A transgender person may feel like a man in a woman’s body, or a woman in a man’s body. Some transgender people are also transsexual: They prefer to live as members of the other sex. Some transsexual people (about three times as many men as women) may seek medical treatment (including sex-reassignment surgery) to achieve their preferred gender identity (Van Kesteren et al., 1997).

115

Note that gender identity is distinct from sexual orientation (the direction of one’s sexual attraction). Transgender people may be sexually attracted to people of the opposite birth sex (heterosexual), the same birth sex (homosexual), both sexes (bisexual), or to no one at all (asexual).

Transgender people may express their gender identity by dressing as a person of the other biological sex typically would. Most who dress this way are biological males who are attracted to women (APA, 2010). The British comedian Eddie Izzard, who regularly dresses in women’s clothes during his performances, explains: “Most transvestites fancy girls.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 4.4

What are gender roles, and what do their variations tell us about our human capacity for learning and adaptation?

Gender roles are sets of expected behaviors for females or for males. Gender roles vary widely in different cultures, which is proof that we are very capable of learning and adapting to the social demands of different environments.