Sexual Orientation: Why Do We Differ?

4-9 What has research taught us about sexual orientation?

As noted earlier in this chapter, we express the direction of our sexual interest in our sexual orientation—our enduring sexual attraction toward others. Sexual orientation appears to exist along a continuum, ranging from exclusive interest in our own sex to complete interest in the other sex. Those of us attracted to people of

As noted earlier in this chapter, we express the direction of our sexual interest in our sexual orientation—our enduring sexual attraction toward others. Sexual orientation appears to exist along a continuum, ranging from exclusive interest in our own sex to complete interest in the other sex. Those of us attracted to people of

121

- our own sex have a homosexual (gay or lesbian) orientation.

- the other sex have a heterosexual (straight) orientation.

- both sexes have a bisexual orientation.

As far as we know, in all cultures, heterosexuality has prevailed and bisexuality and homosexuality have endured. But as survey results show, cultures vary widely in their social norms for acceptable partners. In Kenya and Nigeria, 98 percent have said that homosexuality is “never justified” (Pew, 2006). In the United States, 60 percent of people say that homosexuality should be accepted, which lags behind countries such as Spain (88 percent), Germany (87 percent), France (77 percent), and Britain (76 percent) (Pew, 2013). In the United States, a smaller but increasing majority (60 percent) have recently supported accepting homosexuality.

A large number of Americans—13 percent of women and 5 percent of men—say they have had some same-sex sexual contact during their lives (Chandra et al., 2011). Still more have had an occasional same-sex fantasy. Far fewer (3.4 percent) identify themselves as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (Gates & Newport, 2012).

How many people in Europe and the United States are exclusively homosexual? About 10 percent, as the popular press has often assumed? Nearly 25 percent, as Americans, on average, estimated in a 2011 Gallup survey (Morales, 2011)? The most accurate figure seems to be about 3 percent of men and 1 or 2 percent of women (Chandra et al., 2011; Herbenick et al., 2010a; Wells et al., 2011). Active bisexuality is rarer (less than 1 percent). In one survey of 7076 Dutch adults, only 12 people said they were actively bisexual (Sandfort et al., 2001).

Heterosexuals may wonder what it feels like to be the “odd man out” in a straight culture. Imagine that you have found “the one”—a perfect partner of the other sex. How would you feel if you weren’t sure who you could trust with knowing you had these feelings? How would you react if most movies, TV shows, and advertisements showed only same-sex relationships? How would you like hearing that many people wouldn’t vote for a political candidate who favors other-sex marriage? And how would you feel if children’s organizations and adoption agencies thought you might not be safe or trustworthy because you’re attracted to people of the other sex?

Facing such reactions, homosexual people may at first try to ignore or deny their desires, hoping they will go away. They may even try to change, through psychotherapy, willpower, or prayer. But the feelings typically persist, as do those of heterosexual people—who are similarly unable to become homosexual on command (Haldeman, 1994, 2002; Myers & Scanzoni, 2005).

Most psychologists view sexual orientation as neither willfully chosen nor willfully changed. “Efforts to change sexual orientation are unlikely to be successful and involve some risk of harm,” declared a 2009 American Psychological Association report. In 1973, the American Psychiatric Association dropped homosexuality from its list of “mental illnesses.” In 1993, The World Health Organization did the same, as did Japan’s and China’s psychiatric associations in 1995 and 2001.

Some have noted that rates of depression and attempted suicide are higher among gays and lesbians. Many psychologists believe, however, that these symptoms may result from experiences with bullying and discrimination (Sandfort et al., 2001; Warner et al., 2004). “Homosexuality, in and of itself, is not associated with mental disorders or emotional or social problems,” declared the American Psychological Association (2007).

Sexual orientation usually endures, especially for men (Chivers, 2005; Diamond, 2008; Peplau & Garnets, 2000). Women’s sexual orientation tends to be less strongly felt and more variable (Baumeister et al., 2000). This may help explain why more women than men report having had at least one same-sex sexual contact, even though the male homosexuality rate exceeds the female rate (Chandra et al., 2011).

122

Environment and Sexual Orientation

So, if we do not choose our sexual orientation and (especially for males) seem unable to change it, where do these preferences come from? See if you can predict the answers (Yes or No) to these questions:

- Is homosexuality linked with problems in a child’s relationships with parents, such as with an overpowering mother and a weak father, or a possessive mother and a hostile father?

- Does homosexuality involve a fear or hatred of people of the other sex, leading individuals to direct their desires toward members of their own sex?

- Is sexual orientation linked with levels of sex hormones currently in the blood?

- As children, were most homosexuals molested, seduced, or otherwise sexually victimized by an adult homosexual?

Note that the scientific question is not “What causes homosexuality?” (or “What causes heterosexuality?”) but “What causes differing sexual orientations?” In pursuit of answers, psychological science compares the backgrounds and physiology of people whose sexual orientations differ.

Hundreds of studies have indicated that the answers to these questions have been No, No, No, and No (Storms, 1983). In a search for possible environmental influences on sexual orientation, Kinsey Institute investigators interviewed nearly 1000 homosexual and 500 heterosexual people. They assessed almost every imaginable psychological cause of homosexuality—parental relationships, childhood sexual experiences, peer relationships, and dating experiences (Bell et al., 1981; Hammersmith, 1982). Their findings: Homosexual people were no more likely than heterosexual people to have been smothered by maternal love or neglected by their father. And consider this: If “distant fathers” were more likely to produce homosexual sons, then shouldn’t boys growing up in father-absent homes more often be gay? (They are not.) And shouldn’t the rising number of such homes have led to a noticeable increase in the gay population? (It has not.) Most children raised by gay or lesbian parents grow up to be heterosexual and well-adjusted adults (Gartrell & Bos, 2010).

What have we learned from a half-century’s theory and research? If there are environmental factors that influence sexual orientation, we haven’t yet found them.

Biology and Sexual Orientation

The lack of evidence for environmental influences on homosexuality has led researchers to explore several lines of biological evidence:

- Same-sex attraction in other species

- Gay-straight brain differences

- Genetic influences

- Prenatal influences

- Gay-straight trait differences

Same-Sex Attraction in Other Species

In Boston’s Public Gardens, caretakers solved the mystery of why a much-loved swan couple’s eggs never hatched. Both swans were female. In New York City’s Central Park Zoo, penguins Silo and Roy spent several years as devoted same-sex partners. Same-sex sexual behaviors have also been observed in several hundred other species, including grizzlies, gorillas, monkeys, flamingos, and owls (Bagemihl, 1999). Among rams, for example, some 7 to 10 percent (to sheep-breeding ranchers, the “duds”) display same-sex attraction by shunning ewes and seeking to mount other males (Perkins & Fitzgerald, 1997). Homosexual behavior seems a natural part of the animal world.

Gay-Straight Brain Differences

Might the structure and function of heterosexual and homosexual brains differ? With this question in mind, researcher Simon LeVay (1991) studied sections of the hypothalamus taken from deceased heterosexual and homosexual people. (The hypothalamus is a brain structure linked to sexual behavior.) As a homosexual man, LeVay wanted to do “something connected with my gay identity.” To avoid biasing the results, he did a blind study: He didn’t know which donors were gay or straight. After nine months of peering through his microscope at a cell cluster that came in different sizes, he consulted the donor records. The cell cluster was reliably larger in heterosexual men than in women and homosexual men. “I was almost in a state of shock,” LeVay said (1994). “I took a walk by myself on the cliffs over the ocean. I sat for half an hour just thinking what this might mean.”

123

It should not surprise us that brains differ with sexual orientation. Remember, everything psychological is simultaneously biological. But when did the brain difference begin? At conception? During childhood or adolescence? Did experience produce the difference? Or was it genes or prenatal hormones (or genes via prenatal hormones)?

LeVay does not view this cell cluster as an “on-off button” for sexual orientation. Rather, he believes it is part of a brain pathway that is active during sexual behavior. He agrees that sexual behavior patterns could influence the brain’s anatomy. Neural pathways in our brain do grow stronger with use. In fish, birds, rats, and humans, brain structures vary with experience—including sexual experience (Breedlove, 1997). But LeVay believes it more likely that brain anatomy influences sexual orientation. His hunch seems confirmed by the discovery of a similar difference found between the 7 to 10 percent of male sheep that display same-sex attraction and the 90+ percent attracted to females (Larkin et al., 2002; Roselli et al., 2002, 2004). Moreover, such differences seem to develop soon after birth, perhaps even before birth (Rahman & Wilson, 2003).

“Gay men simply don’t have the brain cells to be attracted to women.”

Simon LeVay, The Sexual Brain, 1993

Since LeVay’s brain structure discovery, other researchers have replicated his study with similar results (Byne et al., 2001). Still others have reported additional differences in the way that gay and straight brains function. Gay men show the greatest brain arousal when they view images of other men, straight men when viewing women (Safron et al., 2007). When straight women were given a whiff of a scent derived from men’s sweat (which contains traces of male hormones), an area of their hypothalamus became active (Savic et al., 2005). Gay men’s brains responded similarly to the men’s scent. Straight men’s brains did not. For them, only a female scent triggered the arousal response. In a similar study, lesbians’ responses differed from those of straight women (Kranz & Ishai, 2006; Martins et al., 2005). Clearly, the brain is a sex organ.

Genetic Influences

Findings from three sets of studies suggest a genetic influence on sexual orientation.

- Family studies: Human sexuality researchers report that homosexuality appears to run in families (Mustanski & Bailey, 2003) and that male homosexuality is often transmitted through the mother’s side of the family (Plomin et al., 1997).

- Twin studies: Twin studies show that a homosexual orientation is somewhat more likely to be shared by identical twins (who have identical genes) than by fraternal twins (whose genes are not identical) (Alanko et al., 2010; Lángström et al., 2008, 2010). However, sexual orientation differs in many identical twin pairs (especially female twins). This means that other factors besides genes must play a role.

- Fruit fly studies: Laboratory experiments on fruit flies have changed their sexual orientation and behavior by altering a single gene (Dickson, 2005). During courtship, females acted like males (pursuing other females) and males acted like females (Demir & Dickson, 2005).

It’s likely that multiple genes, possibly interacting with other influences, shape human sexual orientation. In search of such genetic markers, one study financed by the U.S. National Institutes of Health is analyzing the genes of more than 1000 gay brothers.

Prenatal Influences

Twins share not only genes, but also a prenatal environment. In explaining sexual orientation, two sets of findings indicate that the prenatal environment matters.

HORMONAL ACTIVITY A critical period for human brain development occurs between the middle of the second and fifth months after conception (Ellis & Ames, 1987; Gladue, 1990; Meyer-Bahlburg, 1995). A fetus (either male or female) exposed to typical female hormone levels during this period may be attracted to males in later life. When pregnant sheep were injected with testosterone during a similar critical period, their female offspring later showed homosexual behavior (Money, 1987).

124

“Modern scientific research indicates that sexual orientation is…partly determined by genetics, but more specifically by hormonal activity in the womb.”

Glenn Wilson and Qazi Rahman, Born Gay: The Psychobiology of Sex Orientation, 2005

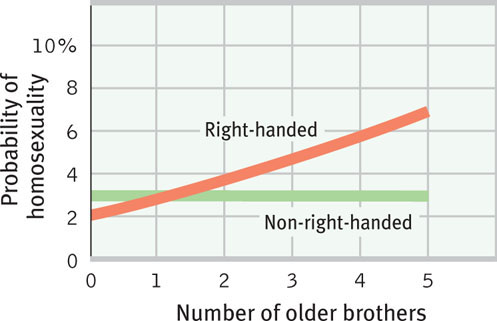

MATERNAL IMMUNE SYSTEM RESPONSES Men who have older brothers are somewhat more likely to be gay—about one-third more likely for each additional older brother (Blanchard, 1997, 2008; Bogaert, 2003) (FIGURE 4.5). If the odds of homosexuality are roughly 2 percent among first sons, they would rise to nearly 3 percent among second sons, 4 percent for third sons, and so on for each additional older brother. This curious effect is called the older-brother or fraternal birth-order effect. Its cause seems biological: The effect does not occur among adopted brothers (Bogaert, 2006). Researchers suspect the mother’s immune system may have a defensive response to substances produced by male fetuses. After each pregnancy with a male fetus, antibodies in her system may grow stronger and may prevent the fetal brain from developing in a typical male pattern. Curiously, the older-brother effect is found only among right-handed men.

Gay-Straight Trait Differences

On several traits, gays and lesbians appear to fall midway between straight females and males (LeVay, 2011; Rahman & Koerting, 2008). Gay men tend to be shorter and lighter than straight men—a difference that appears even at birth. Women in same-sex marriages were mostly heavier than average at birth (Bogaert, 2010; Frisch & Zdravkovic, 2010). Data from 20 studies have also revealed handedness differences: Homosexual participants were 39 percent more likely not to be right-handed (Blanchard, 2008; Lalumière et al., 2000).

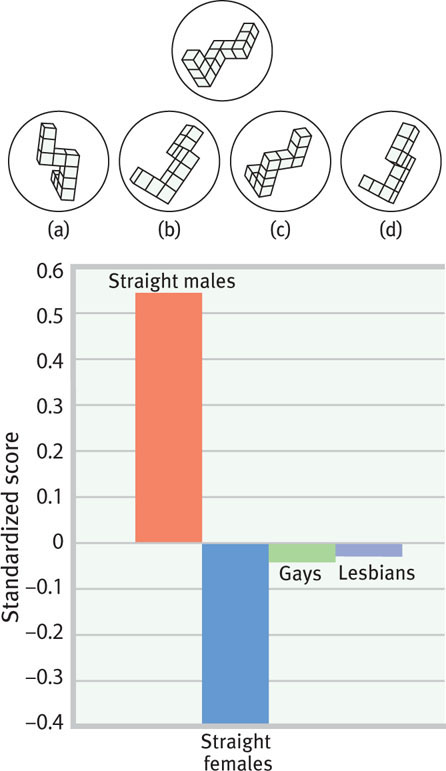

Beyond physical differences, gay-straight spatial abilities also differ. On mental rotation tasks such as the one illustrated in FIGURE 4.6, straight men tend to outscore straight women. The scores of gay men and lesbians fall in between (Rahman et al., 2003, 2008). But both straight women and gay men outperform straight men at remembering objects’ spatial locations in tasks like those found in memory games (Hassan & Rahman, 2007).

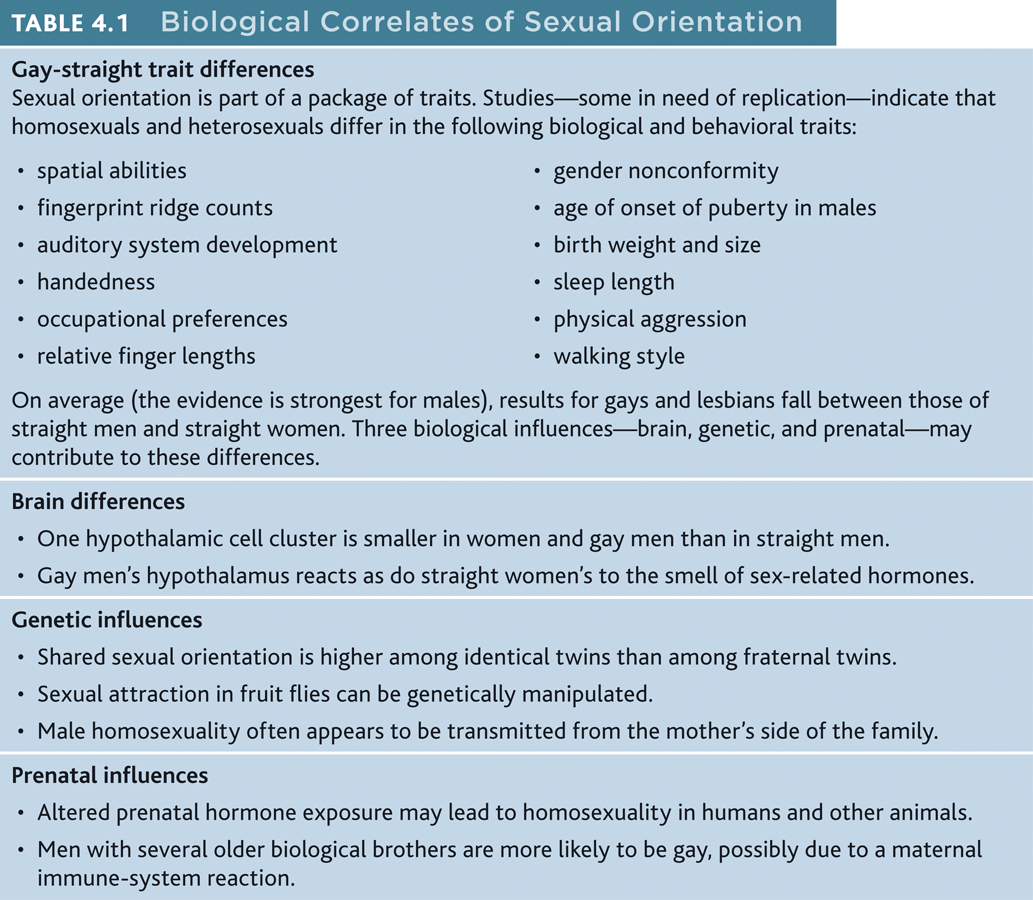

TABLE 4.1 summarizes these and other gay-straight differences.

“There is no sound scientific evidence that sexual orientation can be changed.”

UK Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2009

Taken together, the brain, genetic, and prenatal findings offer strong support for a biological explanation of sexual orientation (LeVay, 2011; Rahman & Koerting, 2008). Although “much remains to be discovered,” concludes Simon LeVay (2011, p. xvii), “the same processes that are involved in the biological development of our bodies and brains as male or female are also involved in the development of sexual orientation.

125

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 4.10

Which THREE of the following five factors have researchers found to have an effect on sexual orientation?

|

b, c, e