An Evolutionary Explanation of Human Sexuality

4-10 How might evolutionary psychologists explain gender differences in sexuality and mating preferences?

Having faced many similar challenges throughout history, men and women have adapted in similar ways. Whether male or female, we eat the same foods, avoid the same predators, and perceive, learn, and remember in much the same way. It is only in areas where we have faced differing adaptive challenges—most obviously in behaviors related to reproduction—that we differ, say evolutionary psychologists.

Having faced many similar challenges throughout history, men and women have adapted in similar ways. Whether male or female, we eat the same foods, avoid the same predators, and perceive, learn, and remember in much the same way. It is only in areas where we have faced differing adaptive challenges—most obviously in behaviors related to reproduction—that we differ, say evolutionary psychologists.

Gender Differences in Sexuality

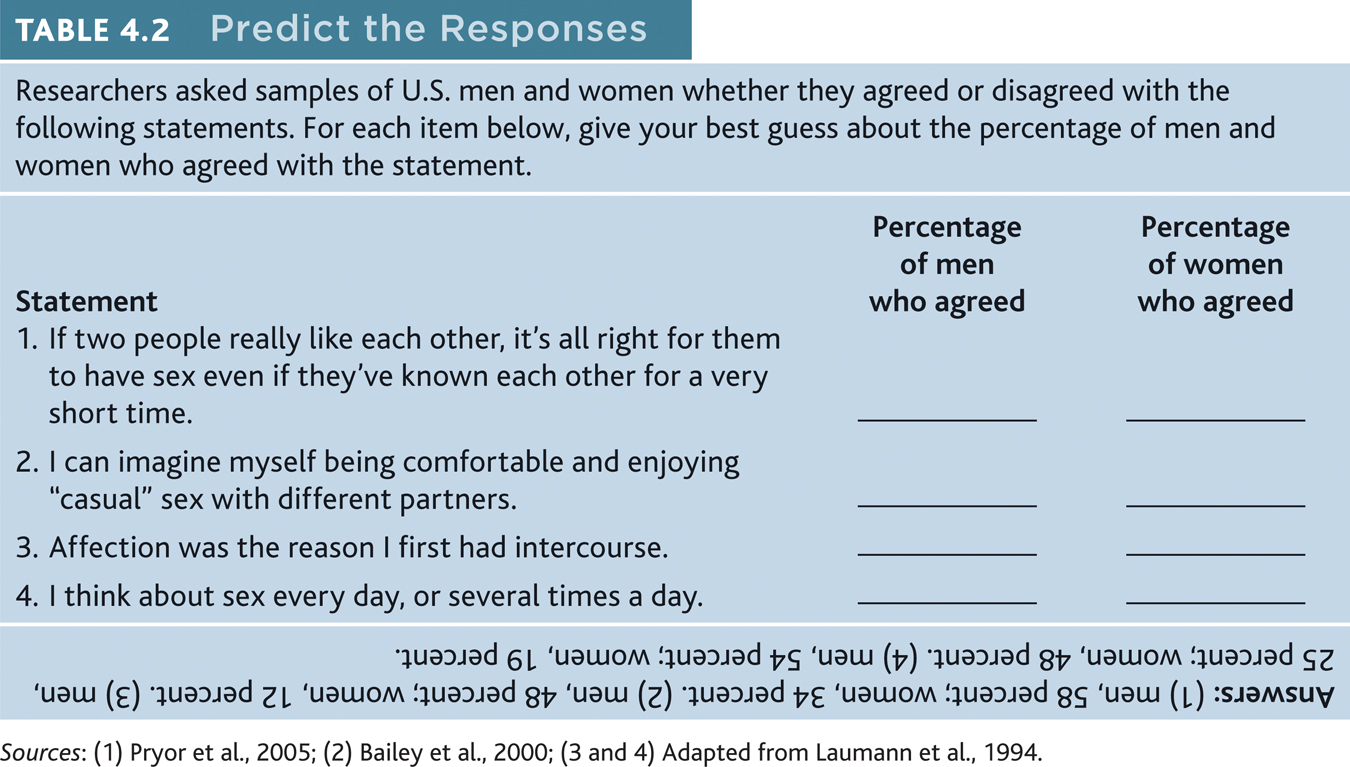

And differ we do. Consider women’s and men’s sex drives. Who desires more frequent sex? Thinks more about sex? Masturbates more often? Sacrifices more to gain sex? Initiates more sex? The answers—men, men, men, men, and men (Baumeister et al., 2001). To see if you can predict such gender differences, take the quiz in TABLE 4.2.

Compared with lesbians, gay men (like straight men) report more interest in uncommitted sex, more responsiveness to visual sexual stimuli, and more concern with their partner’s physical attractiveness (Bailey et al., 1994; Doyle, 2005; Schmitt, 2007). Gay male couples report having sex more often than do lesbian couples (Peplau & Fingerhut, 2007). And in the first year of Vermont’s same-sex civil unions, and among the first 12,000 Massachusetts same-sex marriages, a striking fact emerged. Although men are roughly two-thirds of the gay population, they were only about one-third of those electing legal partnership (Crary, 2009; Rothblum, 2007).

126

Natural Selection and Mating Preferences

The principle of natural selection proposes that nature selects traits and appetites that contribute to survival and reproduction. Evolutionary psychologists use this principle to explain how men and women differ more in the bedroom than in the boardroom. Our natural yearnings, they say, are our genes’ way of reproducing themselves. “Humans are living fossils—collections of mechanisms produced by prior selection pressures” (Buss, 1995).

“It’s not that gay men are oversexed; they are simply men whose male desires bounce off other male desires rather than off female desires.”

Steven Pinker, How the Mind Works, 1997

Why do women tend to be choosier than men when selecting sexual partners? Women have more at stake. To send their genes into the future, a woman must—at a minimum—nurture and protect the fetus growing inside her body for up to nine (often uncomfortable) months. And unlike men, women are limited in how many children they can have between puberty and menopause. No surprise, then, that women prefer partners who will stick around and offer their joint offspring support and protection. Heterosexual women also prefer men who appear mature, dominant, bold, and wealthy (Asendorpf et al., 2011; Gangestad & Simpson, 2000; Singh, 1995). One study of hundreds of Welsh pedestrians asked people to rate a driver pictured at the wheel of a humble Ford Fiesta or a swanky Bentley. Men said a female driver was equally attractive in both cars. Women, however, found a male driver more attractive if he was in the luxury car (Dunn & Searle, 2010). If you put a man in a mating mind-set, how will he try to show he is a “catch”? He’ll buy showy items, express aggressive intentions, and take risks (Baker & Maner, 2009; Griskevicius et al., 2009; Shan et al., 2012; Sundie et al., 2011). Thus, argue evolutionary psychologists, men pair widely; women pair wisely.

For heterosexual men, some desired traits, such as a woman’s smooth skin and youthful shape, cross place and time (Buss, 1994). To evolutionary psychologists, these traits convey health and fertility. A man who mates with such women thus stands a better chance of sending his genes into the future. And sure enough, men feel most attracted to women whose waists (thanks to their genes or their surgeons) are roughly a third narrower than their hips—a sign of future fertility (Perilloux et al., 2010). Even blind men show this preference for women with a low waist-to-hip ratio (Karremans et al., 2010).

127

There is a principle at work here, say evolutionary psychologists: Nature selects behaviors that increase the likelihood of sending one’s genes into the future. As mobile gene machines, we are designed to prefer whatever worked for our ancestors in their environments. They were predisposed to act in ways that would produce grandchildren. Had they not been, we wouldn’t be here. And as carriers of their genetic legacy, we are similarly predisposed.

Why might “gay genes” persist? Same-sex couples cannot naturally reproduce. Evolutionary psychologists suggest a possible answer: the fertile female theory. The theory goes like this. In generations before the birth of a homosexual man, women in that family have tended to have larger-than-normal families (Camperio-Caini et al., 2004; Iemmola & Camperio-Caini, 2009). Might the genes that dispose women to be strongly attracted to men, and therefore to have more children, also dispose some men to be attracted to men (LeVay, 2011)? If so, this could help explain why “gay genes” exist.

Critiquing the Evolutionary Perspective

4-11 What are the key criticisms of evolutionary explanations of human sexuality, and how do evolutionary psychologists respond?

Most psychologists agree that natural selection prepares us for survival and reproduction. But critics say there is a weakness in the reasoning evolutionary psychologists use to explain our mating preferences. Let’s consider how an evolutionary psychologist might explain the findings in a startling study (Clark & Hatfield, 1989), and how a critic might object.

Participants were approached by a “stranger” of the other sex (someone working for the experimenter). The stranger remarked, “I have been noticing you around campus. I find you to be very attractive,” and then asked one of three questions:

- Would you go out with me tonight?

- Would you come over to my apartment tonight?

- Would you go to bed with me tonight?

What percentage of men and women do you think agreed to each offer? According to the evolutionary explanation of genetic differences in sexuality, women will be choosier than men in selecting their sexual partners and will be less willing to hop in bed with a complete stranger. In fact, not a single woman—and 70 percent of men—agreed to question 3. A recent repeat of this study produced a similar result in France (Guéguen, 2011). The research seemed to support an evolutionary explanation.

Or did it? Critics note that evolutionary psychologists start with an effect—in this case, that men are more likely to accept casual sex offers—and work backward to explain what happened. What if research showed the opposite effect? If men refused an offer for casual sex, might we not reason that men who partner with one woman for life make better fathers, whose children more often survive?

Other critics ask why we should try to explain today’s behavior based on decisions our ancestors made thousands of years ago. They believe social learning theory offers a better, more immediate explanation for these results. Perhaps women learn scripts by watching and imitating others in their cultures. Those scripts may teach them that sexual encounters with strangers are dangerous, and that men who ask for casual sex will not offer women much sexual pleasure (Conley, 2011). This explanation of the study’s effects proposes that women react to sexual encounters in ways that their modern culture teaches them.

A third criticism focuses on the social consequences of accepting an evolutionary explanation. Are heterosexual men truly hard-wired to have sex with any woman who approaches them? If so, does this mean that men have no moral responsibility to remain faithful to their partners? Does this explanation excuse men’s sexual aggression—“boys will be boys”—because of our evolutionary history?

128

Evolutionary psychologists agree that much of who we are is not hard-wired. “Evolution forcefully rejects a genetic determinism,” insisted one research team (Confer et al., 2010). Evolutionary psychologists also remind us that men and women, having faced similar adaptive problems, are far more alike than different. Natural selection has prepared us to be flexible. We humans have a great capacity for learning and social progress. We adjust and respond to varied environments. We adapt and survive, whether we live in the Arctic or the desert.

Evolutionary psychologists also agree with their critics that some traits and behaviors, such as suicide, are hard to explain in terms of natural selection (Barash, 2012; Confer et al., 2010). But they ask us to remember evolutionary psychology’s testable predictions. We can, for example, scientifically test hypotheses such as: Do we tend to favor others to the extent that they share our genes or can later return our favors? (The answer is Yes.) And they remind us that the study of how we came to be need not dictate how we ought to be. Understanding our tendencies sometimes helps us overcome them.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 4.11

How do evolutionary psychologists explain gender differences in sexuality?

Evolutionary psychologists theorize that women have inherited their ancestors’ tendencies to be more cautious sexually, because of the challenges associated with incubating and nurturing offspring. Men have inherited an inclination to be more casual about sex, because their act of fathering requires a smaller investment.

Question 4.12

What are the three main criticisms of the evolutionary explanation of human sexuality?

(1) It starts with an effect and works backward to propose an explanation. (2) Unethical and immoral men could use such explanations to rationalize their behavior toward women. (3) This explanation may overlook the effects of cultural expectations and socialization.