How Do We Learn?

6-1 What are some basic forms of learning?

One way we learn is by association. Our minds naturally connect events that occur in sequence. Suppose you see and smell freshly baked bread, eat some, and find it satisfying. The next time you see and smell fresh bread, you will expect that eating it will again be satisfying. So, too, with sounds. If you associate a sound with a frightening consequence, hearing the sound alone may trigger your fear. As one 4-year-old said after watching a TV character get mugged, “If I had heard that music, I wouldn’t have gone around the corner!” (Wells, 1981).

One way we learn is by association. Our minds naturally connect events that occur in sequence. Suppose you see and smell freshly baked bread, eat some, and find it satisfying. The next time you see and smell fresh bread, you will expect that eating it will again be satisfying. So, too, with sounds. If you associate a sound with a frightening consequence, hearing the sound alone may trigger your fear. As one 4-year-old said after watching a TV character get mugged, “If I had heard that music, I wouldn’t have gone around the corner!” (Wells, 1981).

Learned associations also feed our habitual behaviors (Wood & Neal, 2007). Habits can form when we repeat behaviors in a given context—sleeping in the same comfy position in bed, walking the same path to class, eating buttery popcorn in the local theater. As behavior becomes linked with the context, our next experience of that context will evoke our habitual response.

How long does it take to form such habits? To find out, researchers asked 96 university students to choose some healthy behavior, such as running before dinner or eating fruit with lunch, and to perform it daily for 84 days. The students also recorded whether the behavior felt automatic (something they did without thinking and would find it hard not to do). When did the behaviors turn into habits? On average after about 66 days (Lally et al., 2010). (Is there something you’d like to make a routine part of your life? Just do it every day for two months, or a bit longer for exercise, and you likely will find yourself with a new habit.)

Other animals also learn by association. To protect itself, the sea slug Aplysia withdraws its gill when squirted with water. If the squirts continue, as happens naturally in choppy water, the withdrawal response weakens. But if the sea slug repeatedly receives an electric shock just after being squirted, its response to the squirt instead grows stronger. The animal has learned that the squirt signals an upcoming shock.

Complex animals can learn to link outcomes with their own responses. An aquarium seal will repeat behaviors, such as slapping and barking, that prompt people to toss it a herring.

By linking two events that occur close together, the sea slug and the seal are exhibiting associative learning. The sea slug associated the squirt with an upcoming shock. The seal associated its slapping and barking with a herring treat. Each animal has learned something important to its survival: predicting the immediate future.

This process of learning associations is conditioning, and it takes two main forms:

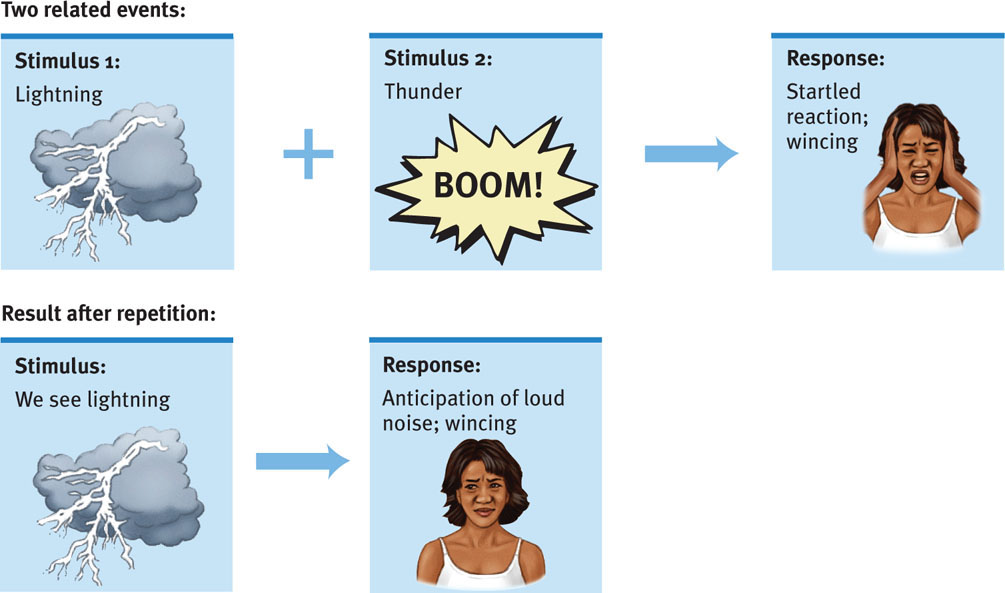

- In classical conditioning, we learn to associate two stimuli and thus to anticipate events. (A stimulus is any event or situation that evokes a response.) We learn that a flash of lightning will be followed by a crack of thunder, so when lightning flashes nearby, we start to brace ourselves (FIGURE 6.1).

FIGURE 6.1 Classical conditioning

FIGURE 6.1 Classical conditioning - In operant conditioning, we learn to associate a response (our behavior) and its consequence. Thus, we (and other animals) learn to repeat acts followed by good results (FIGURE 6.2) and to avoid acts followed by bad results.

FIGURE 6.2 Operant conditioning

FIGURE 6.2 Operant conditioning

Conditioning is not the only form of learning. Through cognitive learning we acquire mental information that guides our behavior. Observational learning, one form of cognitive learning, lets us learn from others’ experiences. Chimpanzees, for example, sometimes learn behaviors merely by watching others. If one animal sees another solve a puzzle and gain a food reward, the observer may perform the trick more quickly. So, too, in humans: We look and we learn.

By learning, we humans are able to adapt to our environments. We learn to expect and prepare for significant events such as food or pain (classical conditioning). We learn to repeat acts that bring good results and to avoid acts that bring bad results (operant conditioning). We learn new behaviors by observing events and by watching others, and through language we learn things we have neither experienced nor observed (cognitive learning).

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 6.1

Why are habits, such as having something sweet with that cup of coffee, so hard to break?

Why are habits, such as having something sweet with that cup of coffee, so hard to break?

Habits form when we repeat behaviors in a given context and, as a result, learn associations—often without our awareness. For example, we may have eaten a sweet pastry with a cup of coffee often enough to associate the flavor of the coffee with the treat, so that the cup of coffee alone just doesn’t seem right anymore!