Classical Conditioning

For many people, the name Ivan Pavlov (1849–1936) rings a bell. His early twentieth-century experiments—now psychology’s most famous research—are classics. The process he explored we justly call classical conditioning.

For many people, the name Ivan Pavlov (1849–1936) rings a bell. His early twentieth-century experiments—now psychology’s most famous research—are classics. The process he explored we justly call classical conditioning.

Pavlov’s Experiments

6-2 What is classical conditioning, and how does it demonstrate associative learning?

For his studies of digestion, Pavlov (who held a medical degree) earned Russia’s first Nobel Prize in 1904. But his novel experiments on learning, which consumed the last three decades of his life, earned Pavlov his place in history.

Pavlov’s new direction came when his creative mind seized on what seemed to others an unimportant detail. Without fail, putting food in a dog’s mouth caused the animal to drool—to salivate. Moreover, the dog began salivating not only to the taste of the food but also to the mere sight of the food or the food dish. The dog even drooled at the sight of the person delivering the food or the sound of that person’s approaching footsteps. At first, Pavlov considered these “psychic secretions” an annoyance. Then he realized they pointed to a simple but important form of learning.

Pavlov and his assistants tried to imagine what the dog was thinking and feeling as it drooled in anticipation of the food. This only led them into useless debates. So, to make their studies more objective, they experimented. To rule out other possible influences, they isolated the dog in a small room, placed it in a harness, and attached a device to measure its saliva. Then, from the next room, they presented food. First, they slid in a food bowl. Later, they blew meat powder into the dog’s mouth at a precise moment. Finally, they paired various neutral stimuli (NS)—events the dog could see or hear but didn’t associate with food—with food in the dog’s mouth. If a sight or sound regularly signaled the arrival of food, would the dog learn the link? If so, would it begin salivating in anticipation of the food?

170

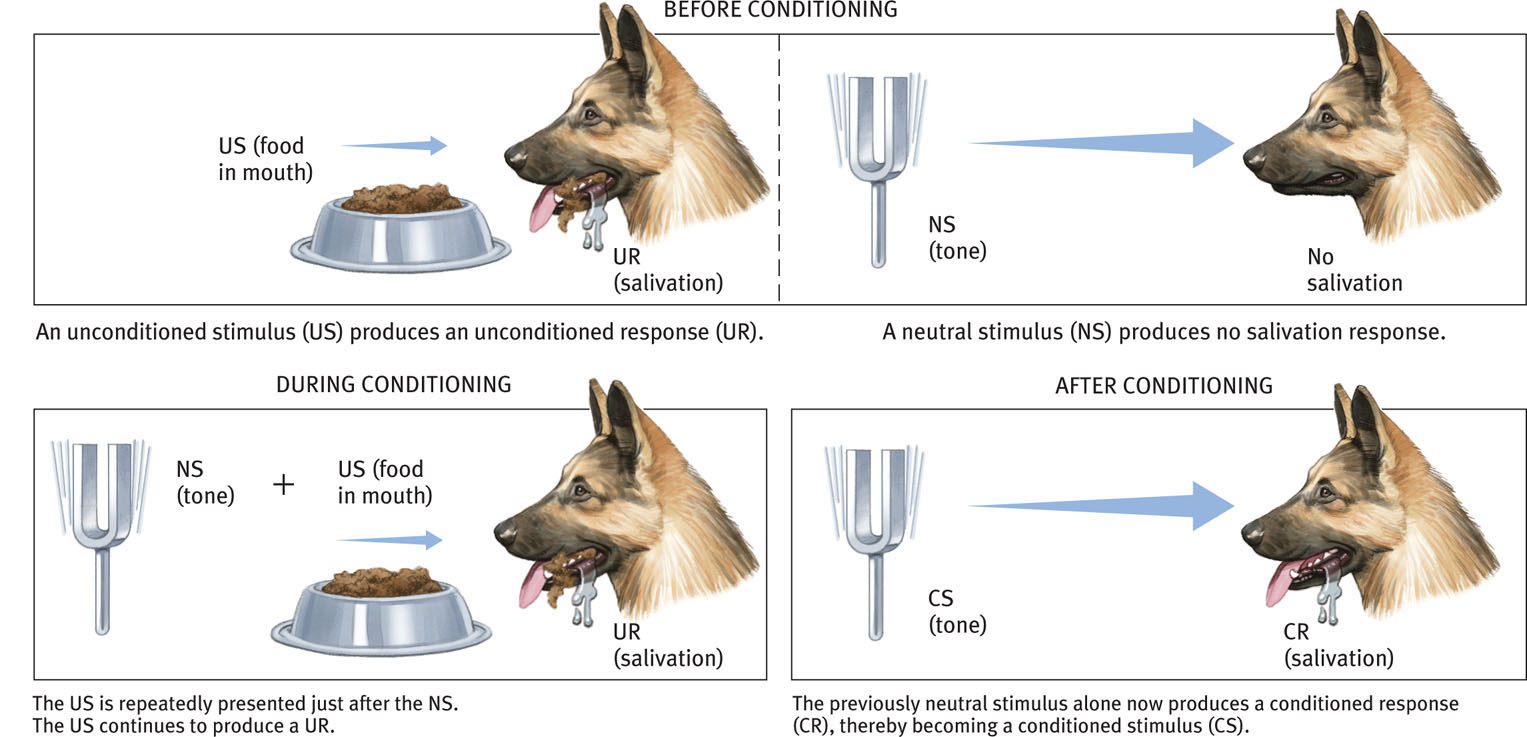

The answers proved to be Yes and Yes. Just before placing food in the dog’s mouth to produce salivation, Pavlov sounded a tone. After several pairings of tone and food, the dog got the message. Anticipating the meat powder, it began salivating to the tone alone. In later experiments, a buzzer, a light, a touch on the leg, even the sight of a circle set off the drooling.

A dog doesn’t learn to salivate in response to food in its mouth. Food in the mouth automatically, unconditionally, triggers this response. Thus, Pavlov called the drooling an unconditioned response (UR). And he called the food an unconditioned stimulus (US).

Salivating in response to a tone, however, is learned. Because it is conditional upon the dog’s linking the tone with the food (FIGURE 6.3), we call this response the conditioned response (CR). The stimulus that used to be neutral (in this case, a previously meaningless tone that now triggers drooling) is the conditioned stimulus (CS). Remembering the difference between these two kinds of stimuli and responses is easy: Conditioned = learned; unconditioned = unlearned.

If Pavlov’s demonstration of associative learning was so simple, what did he do for the next three decades? What discoveries did his research factory publish in his 532 papers on salivary conditioning (Windholz, 1997)? He and his associates explored five major conditioning processes: acquisition, extinction, spontaneous recovery, generalization, and discrimination.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 6.2

An experimenter sounds a tone just before delivering an air puff to your blinking eye. After several repetitions, you blink to the tone alone. What is the NS? The US? The UR? The CS? The CR?

NS = tone before conditioning; US = air puff; UR = blink to air puff; CS = tone after conditioning; CR = blink to tone.

Acquisition

6-3 What parts do acquisition, extinction, spontaneous recovery, generalization, and discrimination play in classical conditioning?

Acquisition is the first stage in classical conditioning. This is the point when Pavlov’s dogs learned the link between the NS (the tone, the light, the touch) and the US (the food). To understand this stage, Pavlov and his associates wondered: How much time should pass between presenting the neutral stimulus and the food? In most cases, not much—half a second usually works well.

171

What do you suppose would happen if the food (US) appeared before the tone (NS) rather than after? Would conditioning occur? Not likely. With only a few exceptions, conditioning doesn’t happen when the NS follows the US. Remember, classical conditioning is biologically adaptive because it helps humans and other animals prepare for good or bad events. To Pavlov’s dogs, the originally neutral tone became a CS after signaling an important biological event—the arrival of food (US). To deer in the forest, the snapping of a twig (CS) may signal a predator’s approach (US). If the good or bad event has already occurred, the tone or the sound won’t help the animal prepare.

More recent research on male Japanese quail shows how a CS can signal another important biological event (Domjan, 1992, 1994, 2005). Just before presenting a sexually approachable female quail, the researchers turned on a red light. Over time, as the red light continued to announce the female’s arrival, the light caused the male quail to become excited. They developed a preference for their cage’s red-light district. When a female appeared, they mated with her more quickly and released more semen and sperm (Matthews et al., 2007). All in all, the quail’s capacity for classical conditioning gives it a reproductive edge.

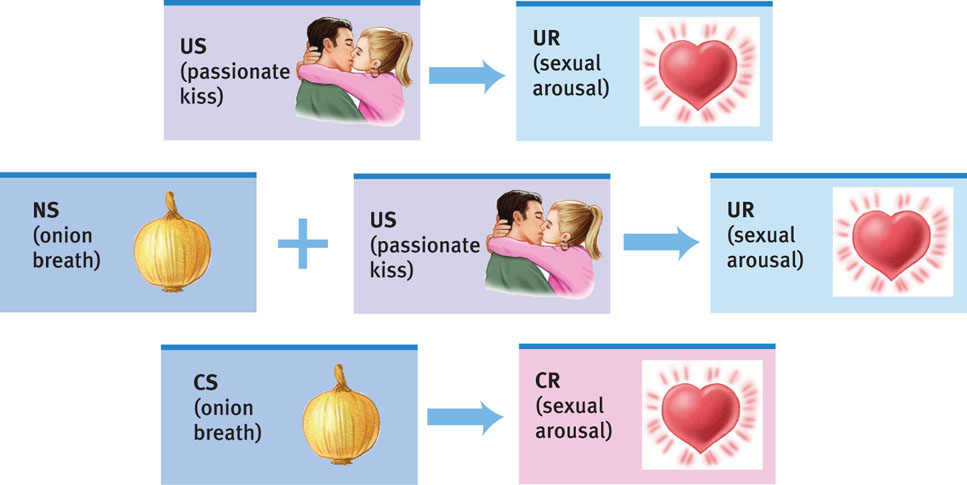

Can objects, sights, and smells associated with sexual pleasure become conditioned stimuli for human sexual arousal, too? Indeed they can (Byrne, 1982). Onion breath does not usually produce sexual arousal (FIGURE 6.4). But when repeatedly paired with a passionate kiss, it can become a CS and do just that. The larger lesson: Conditioning helps an animal survive and reproduce—by responding to cues that help it gain food, avoid dangers, locate mates, and produce offspring (Hollis, 1997).

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 6.3

In horror movies, sexually arousing images of women are sometimes paired with violence against women. Based on classical conditioning principles, what might be an effect of this pairing?

If viewing an attractive nude or seminude woman (a US) elicits sexual arousal (a UR), then pairing the US with a new stimulus (violence) could turn the violence into a conditioned stimulus (CS) that also becomes sexually arousing, a conditioned response (CR).

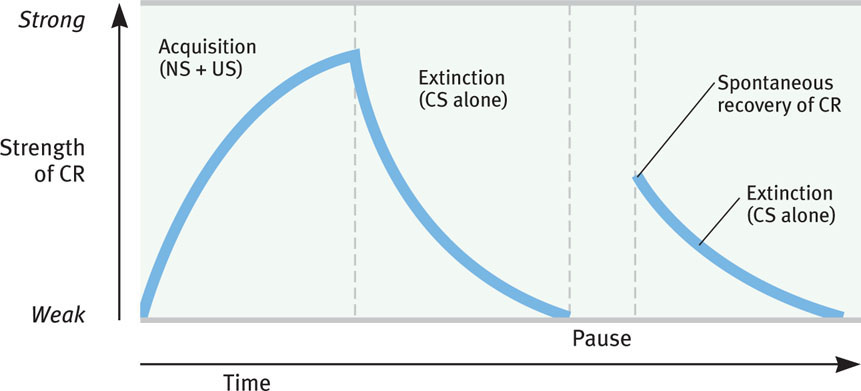

Extinction and Spontaneous Recovery

What would happen, Pavlov wondered, if after conditioning, the CS occurred repeatedly without the US? If the tone sounded again and again, but no food appeared, would the tone still trigger drooling? The answer was mixed. The dogs salivated less and less, a reaction known as extinction—a drop-off in responses when a CS (tone) no longer signals an upcoming US (food). But the dogs began drooling to the tone again if Pavlov scheduled several tone-free hours. This spontaneous recovery—the reappearance of a (weakened) CR after a pause—suggested to Pavlov that extinction was suppressing the CR rather than eliminating it (FIGURE 6.5).

172

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 6.4

The first step of classical conditioning, when an NS becomes a CS, is called ________. When a US no longer follows the CS, and the CR becomes weakened, this is called _______.

acquisition; extinction

Generalization

Pavlov and his students noticed that a dog conditioned to the sound of one tone also responded somewhat to the sound of a new and different tone. Likewise, a dog conditioned to salivate when rubbed would also drool a bit when scratched or when touched on a different body part (Windholz, 1989). This tendency to respond similarly to stimuli that resemble the CS is called generalization.

Generalization can be adaptive, as when toddlers taught to fear moving cars also become afraid of moving trucks and motorcycles. And generalized fears can linger. One Argentine writer who had been tortured still flinches when he sees black shoes—his first glimpse of his torturers as they approached his cell. This generalized fear response was found in laboratory studies comparing abused and non-abused children (Pollak et al., 1998). When an angry face appeared on a computer screen, abused children’s brain-wave responses were dramatically stronger and longer lasting.

Generalization helps to explain why we like unfamiliar people more if they look like someone we’ve learned to like rather than dislike. (Researchers demonstrated this by subtly morphing the facial features of someone people had learned to like or dislike onto a novel face [Verosky & Todorov, 2010].)

In all these human examples, people’s emotional reactions to one stimulus have generalized to similar stimuli.

Discrimination

Pavlov’s dogs also learned to respond to the sound of a particular tone and not to other tones. This learned ability to distinguish between a conditioned stimulus (which predicts the US) and other irrelevant stimuli is called discrimination. Being able to recognize differences is adaptive. Slightly different stimuli can be followed by vastly different results. Confronted by a guard dog, your heart may race; confronted by a guide dog, it probably will not.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 6.5

What conditioning principle is affecting the snail’s affections?

generalization

Pavlov’s Legacy

6-4 Why is Pavlov’s work important, and how is it being applied?

What remains today of Pavlov’s ideas? A great deal. Most psychologists now agree that classical conditioning is a basic form of learning. Judged by today’s knowledge, including our understanding of the biological and cognitive influences on conditioning, Pavlov’s ideas were incomplete. But if we see further than Pavlov did, it is because we stand on his shoulders.

Why does Pavlov’s work remain so important? If he had merely taught us that old dogs can learn new tricks, his experiments would long ago have been forgotten. Why should we care that dogs can be conditioned to drool at the sound of a tone? The importance lies first in this finding: Many other responses to many other stimuli can be classically conditioned in many other creatures—in fact, in every species tested, from earthworms to fish to dogs to monkeys to people (Schwartz, 1984). Thus, classical conditioning is one way that virtually all animals learn to adapt to their environment.

Second, Pavlov showed us how a process such as learning can be studied objectively. He was proud that his methods were not based on guesswork about a dog’s mind. The salivary response is a behavior we can measure in cubic centimeters of saliva. Pavlov’s success therefore suggested a scientific model for how the young field of psychology might proceed. That model was to isolate the basic building blocks of complex behaviors and study them with objective laboratory procedures.

173

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 6.6

If the aroma of cake baking makes your mouth water, what is the US? The CS? The CR?

The cake (and its taste) are the US. The associated aroma is the CS. Salivation to the aroma is the CR.

Classical Conditioning in Everyday Life

Other chapters in this text—on motivation and emotion, stress and health, psychological disorders, and therapy—show how Pavlov’s principles can influence human health and well-being. Two examples:

- Drugs given as cancer treatments can trigger nausea and vomiting. Patients may then develop classically conditioned nausea (and sometimes anxiety) to the sights, sounds, and smells associated with the clinic (Hall, 1997). Merely entering the clinic’s waiting room or seeing the nurses can provoke these feelings (Burish & Carey, 1986).

- Former drug users often feel a craving when they are again in the drug-using context. They associate particular people or places with previous highs. Thus, drug counselors advise addicts to steer clear of people and settings that may trigger these cravings (Siegel, 2005).

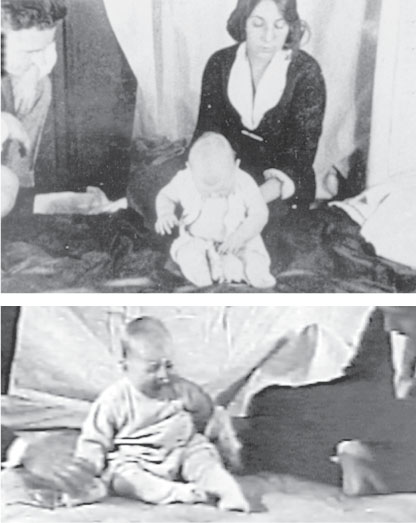

Does Pavlov’s work help us understand our own emotions? John B. Watson thought so. He believed that human emotions and behaviors, though biologically influenced, are mainly a bundle of conditioned responses (1913). Working with an 11-month-old, Watson and Rosalie Rayner (1920; Harris, 1979) showed how specific fears might be conditioned. Like most infants, “Little Albert” feared loud noises but not white rats. Watson and Rayner presented a white rat and, as Little Albert reached to touch it, struck a hammer against a steel bar just behind the infant’s head. After seven repeats of seeing the rat and hearing the frightening noise, Albert burst into tears at the mere sight of the rat. Five days later, he had generalized this startled fear reaction to the sight of a rabbit, a dog, and a sealskin coat, but not to dissimilar objects, such as toys.

For years, people wondered what became of Little Albert. Not until 2009 did some psychologist-sleuths identify him. It seems he was Douglas Merritte, the son of a campus hospital wet nurse who received $1 for her tot’s participation. Sadly, this famous child died at age 6 from complications related to a disease he had suffered since birth (Beck et al., 2009, 2010; Fridlund et al., 2012a, b).

People also wondered what became of Watson. After losing his Johns Hopkins professorship over an affair with Rayner (whom he later married), he joined an advertising agency as the company’s resident psychologist. There he used his knowledge of associative learning in many successful advertising campaigns. One of them, for Maxwell House, helped make the “coffee break” an American custom (Hunt, 1993).

The treatment of Little Albert would be unacceptable by today’s ethical standards. Also, some psychologists, noting that the infant’s fear wasn’t learned quickly, had difficulty repeating Watson and Rayner’s findings with other children. Nevertheless, Little Albert’s learned fears led many psychologists to wonder whether each of us might be a walking storehouse of conditioned emotions. If so, might extinction procedures or even new conditioning help us change our unwanted responses to emotion-arousing stimuli?

Comedian-writer Mark Malkoff extinguished his fear of flying by doing just that. With support from an airline, he faced his fear. Living on an airplane for 30 days and taking 135 flights, he spent 14 hours a day in the air. After a week and a half, Malkoff’s fear had faded, and he began playing games with fellow passengers (NPR, 2009). (His favorite: He’d put one end of a toilet paper roll in the toilet, unroll the rest down the aisle, and flush—sucking down the whole roll in 3 seconds.) In Chapters 13 and 14, we will see more examples of how psychologists use behavioral techniques to treat emotional disorders and promote personal growth.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 6.7

In Watson and Rayner’s experiments, “Little Albert” learned to fear a white rat after repeatedly experiencing a loud noise as the rat was presented. In this experiment, what was the US? The UR? The NS? The CS? The CR?

The US was the loud noise; the UR was the fear response; the NS was the rat before it was paired with the noise; the CS was the rat after pairing; the CR was fear of the rat.

174