Learning by Observation

6-13 How does observational learning differ from associative learning? How may observational learning be enabled by mirror neurons?

Cognition is certainly a factor in observational learning, in which higher animals learn without direct experience, by watching and imitating others. A child who sees his sister burn her fingers on a hot stove learns, without getting burned himself, that hot stoves can burn us. We learn our native languages and all kinds of other specific behaviors by observing and imitating others, a process called modeling.

Cognition is certainly a factor in observational learning, in which higher animals learn without direct experience, by watching and imitating others. A child who sees his sister burn her fingers on a hot stove learns, without getting burned himself, that hot stoves can burn us. We learn our native languages and all kinds of other specific behaviors by observing and imitating others, a process called modeling.

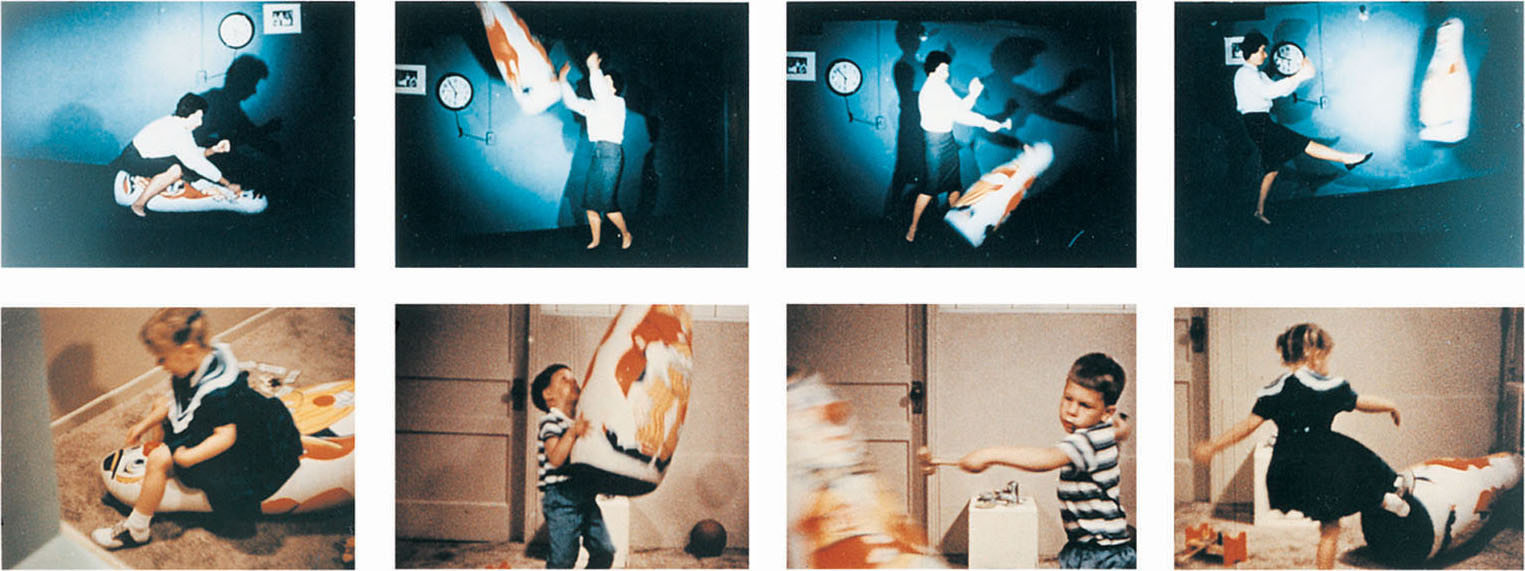

Picture this scene from an experiment by Albert Bandura, the pioneering researcher of observational learning (Bandura et al., 1961). A preschool child works on a drawing. In another part of the room, an adult is building with Tinkertoys. As the child watches, the adult gets up and for nearly 10 minutes pounds, kicks, and throws around the room a large, inflated Bobo doll, yelling, “Sock him in the nose…. Hit him down…. Kick him.”

185

The child is then taken to another room filled with appealing toys. Soon the experimenter returns and tells the child she has decided to save these good toys “for the other children.” She takes the now-frustrated child to a third room containing a few toys, including a Bobo doll. Left alone, what does the child do?

Compared with other children in the study, those who viewed the model’s actions were much more likely to lash out at the doll. Apparently, observing the aggressive outburst lowered their inhibitions. But something more was also at work, for the children often imitated the very acts they had observed and used the very words they had heard (FIGURE 6.9).

That “something more,” Bandura suggested, was this: By watching models, we vicariously (in our imagination) experience what they are experiencing. Through vicarious reinforcement or vicarious punishment, we learn to anticipate a behavior’s consequences in situations like those we are observing. We are especially likely to experience their outcomes vicariously if we identify with them—if we perceive them as

- similar to ourselves.

- successful.

- admirable.

Functional MRI (fMRI) scans show that when people observe someone winning a reward, their own brain reward systems become active, much as if they themselves had won the reward (Mobbs et al., 2009).

Mirrors and Imitation in the Brain

In one of those quirky events that appear in the growth of science, researchers made an amazing discovery.

On a 1991 hot summer day in Parma, Italy, a lab monkey awaited its researchers’ return from lunch. The researchers had implanted a monitoring device in the monkey’s brain, in a frontal lobe region important for planning and acting out movements. The device would alert the researchers to activity in that region. When the monkey moved a peanut into its mouth, for example, the device would buzz. That day, the monkey stared as one of the researchers entered the lab carrying an ice cream cone in his hand. As the researcher raised the cone to lick it, the monkey’s monitor buzzed—as if the motionless monkey had itself made some movement (Blakeslee, 2006; Iacoboni, 2009). The same buzzing had been heard earlier, when the monkey watched humans or other monkeys move peanuts to their mouths.

186

This quirky event, the researchers believed, marked an amazing discovery: a previously unknown type of neuron (Rizzolatti, 2002, 2006). In their view, these mirror neurons provided a neural basis for everyday imitation and observational learning. When a monkey grasps, holds, or tears something, these neurons fire. They likewise fire when the monkey observes another doing so. When one monkey sees, these neurons mirror what another monkey does. (Other researchers continue to debate the existence and importance of mirror neurons and related brain networks [Gallese et al., 2011].)

It’s not just monkey business. Imitation occurs in various animal species, but it is most striking in humans. Our catchphrases, fashions, ceremonies, foods, traditions, morals, and fads all spread by one person copying another. Imitation shapes even very young humans’ behavior (Bates & Byrne, 2010). Shortly after birth, a baby may imitate an adult who sticks out his tongue. By 8 to 16 months, infants imitate various novel gestures (Jones, 2007). By age 12 months, they begin looking where an adult is looking (Meltzoff et al., 2009). And by 14 months, children imitate acts modeled on TV (Meltzoff & Moore, 1997). Even as 2½-year-olds, when many of their mental abilities are near those of adult chimpanzees, young humans surpass chimps at social tasks such as imitating another’s solution to a problem (Herrmann et al., 2007). Children see, children do.

Because of the brain’s responses, emotions are contagious. As we observe others’ postures, faces, voices, and writing styles, we unconsciously mimic them. And by doing that, we grasp others’ states of mind. We mentally imagine their experience and we feel what they are feeling (Bernieri et al., 1994; Ireland & Pennebaker, 2010).

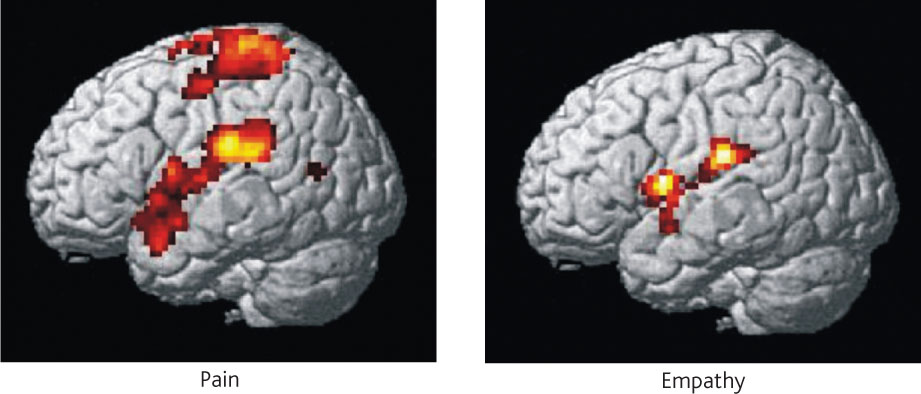

Seeing a loved one’s pain, our faces mirror the loved one’s emotion. And so do our brains. In the fMRI scan in FIGURE 6.10, the pain imagined by an empathic romantic partner triggered some of the same brain activity experienced by the loved one in actual pain (Singer et al., 2004). Even fiction reading may trigger such activity, as we vicariously experience the feelings and actions described (Mar & Oatley, 2008; Speer et al., 2009).

So real are these mental instant replays that we may remember an action we have observed as an action we have actually performed (Lindner et al., 2010). The bottom line: Brain activity underlies our intensely social nature.

Applications of Observational Learning

6-14 What is the impact of prosocial modeling and of antisocial modeling?

So the big news from Bandura’s studies and the mirror-neuron research is that we look, we mentally imitate, and we learn. Models—in our family or neighborhood, or on TV—may have effects, good and bad.

PROSOCIAL EFFECTS The good news is that prosocial (positive, helpful) behavior models can have prosocial effects. People who model nonviolent, helpful behavior can prompt similar behavior in others. India’s Mahatma Gandhi and America’s Martin Luther King, Jr., both drew on the power of modeling, making nonviolent action a powerful force for social change in both countries. Parents are also powerful models. European Christians who risked their lives to rescue Jews from the Nazis usually had a close relationship with at least one parent who modeled a strong moral or humanitarian concern. This was also true for U.S. civil rights activists in the 1960s (London, 1970; Oliner & Oliner, 1988).

Models are most effective when their actions and words are consistent. Sometimes, however, models say one thing and do another. To encourage children to read, read to them and surround them with books and people who read. To increase the odds that your children will practice your religion, worship and attend religious activities with them. Many parents seem to operate according to the principle “Do as I say, not as I do.” Experiments suggest that children learn to do both (Rice & Grusec, 1975; Rushton, 1975). Exposed to a hypocrite, they tend to imitate the hypocrisy—by doing what the model did and saying what the model said.

187

ANTISOCIAL EFFECTS The bad news is that observational learning may have antisocial effects. This helps us understand why abusive parents might have aggressive children, and why many men who beat their wives had wife-battering fathers (Stith et al., 2000). Critics note that being aggressive could be passed along by parents’ genes. But with monkeys, we know it can be environmental. In study after study, young monkeys separated from their mothers and subjected to high levels of aggression grew up to be aggressive themselves (Chamove, 1980). The lessons we learn as children are not easily unlearned as adults, and they are sometimes visited on future generations.

TV shows and Internet videos are a powerful source of observational learning. While watching TV and videos, children may “learn” that bullying is an effective way to control others, that free and easy sex brings pleasure without later misery or disease, or that men should be tough and women gentle. And they have ample time to learn such lessons. During their first 18 years, most children in developed countries spend more time watching TV shows than they spend in school. In the United States, the average teen watches TV shows more than 4 hours a day, the average adult 3 hours (Robinson & Martin, 2009; Strasburger et al., 2010).

TV-show viewers are learning about life from a rather peculiar storyteller, one with a taste for violence. During one closely studied year, nearly 6 in 10 U.S. network and cable programs featured violence. Of those acts, 74 percent went unpunished, and the victims usually showed no pain. Nearly half the events were portrayed as “justified,” and nearly half the attackers were attractive (Donnerstein, 1998). These conditions define the recipe for the violence-viewing effect, described in many studies (Donnerstein, 1998, 2011). To read more about this effect, see Thinking Critically About: Does Viewing Media Violence Trigger Violent Behavior? on the next page.

Screen time’s greatest effect may stem from what it displaces. Children and adults who spend several hours a day in front of a screen spend that many fewer hours in other pursuits—talking, studying, playing, reading, or socializing in real time with friends. What would you have done with your extra time if you had spent even half as many hours in front of a screen, and how might you therefore be different?

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 6.15

Jason’s parents and older friends all smoke, but they advise him not to. Juan’s parents and friends don’t smoke, but they say nothing to deter him from doing so. Will Jason or Juan be more likely to start smoking?

Jason may be more likely to smoke, because observational learning studies suggest that children tend to do as others do and say what they say.

Question 6.16

Match the learning examples (items 1–5) to the following concepts (a–e):

|

|

1. c (You’ve probably learned your way by latent learning.) 2. d (Observational learning may have contributed to your imitating the language modeled by your parents.) 3. a (Through classical conditioning you have associated the smell with the anticipated tasty result.) 4. e (You are biologically predisposed to develop a conditioned taste aversion to foods associated with illness.) 5. b (Through operant conditioning your dog may have come to associate your arrival with attention, petting, and a treat.)

188

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT

Does Viewing Media Violence Trigger Violent Behavior?

Was the judge who in 1993 tried two British 10-year-olds for their murder of a 2-year-old right to suspect that the pair had been influenced by “violent video films”? Were the American media right to wonder if Adam Lanza, the 2012 mass killer of young children and their teachers at Connecticut’s Sandy Hook Elementary School, was influenced by his playing of the violent video games found stockpiled in his home? To understand whether violence viewing leads to violent behavior, researchers have done both correlational and experimental studies (Anderson & Gentile, 2008).

Correlational studies do support this link:

- In the United States and Canada, homicide rates doubled between 1957 and 1974, just when TV was introduced and spreading. Moreover, census regions with later dates for TV service also had homicide rates that jumped later.

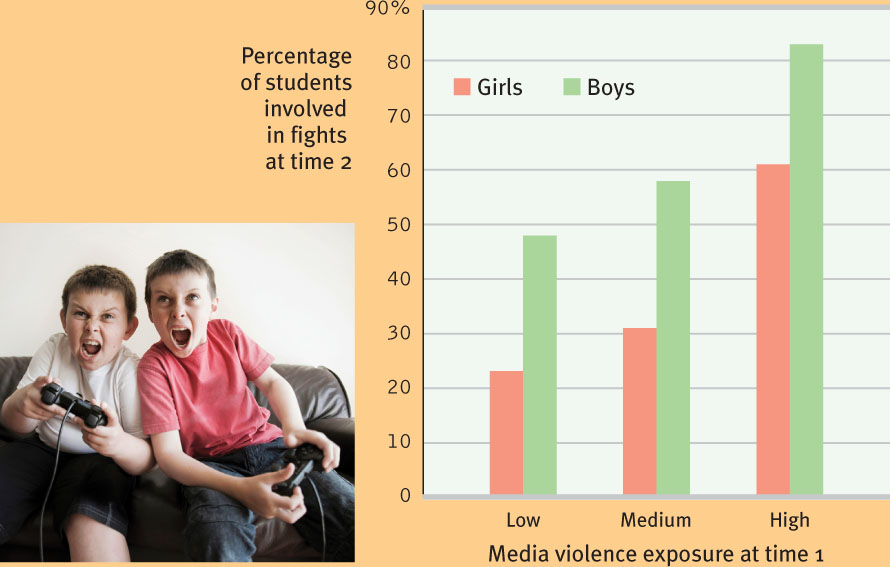

- Elementary schoolchildren with heavy exposure to media violence (via TV, videos, and video games) tend to get into more fights (FIGURE 6.11). As teens, they also are at greater risk for violent behavior (Boxer et al., 2009).

But as we know from Chapter 1, correlation does not prove causation. So these studies do not prove that viewing violence causes aggression (Ferguson, 2009; Freedman, 1988; McGuire, 1986). Maybe aggressive children prefer violent programs. Maybe abused or neglected children are both more aggressive and more often left in front of the TV or computer. Maybe violent programs reflect, rather than affect, violent trends.

To pin down cause and effect, psychologists use experiments. In this case, researchers randomly assigned some viewers to observe violence and others to watch entertaining nonviolence. Does viewing cruelty prepare people, when irritated, to react more cruelly? To some extent, it does. This is especially so when an attractive person commits seemingly justified, realistic violence that goes unpunished and causes no visible pain or harm (Donnerstein, 1998).

This violence-viewing effect seems to stem from at least two factors.

- More than 100 studies confirm that media models glorifying risk-taking behaviors (dangerous driving, extreme sports, unprotected sex) prompt imitation (Fischer et al., 2011; Geen & Thomas, 1986). As children watch violent models, their brains mimic the behavior. After this rehearsal, they become more likely to act out what they’ve observed. In one experiment, violent play increased sevenfold immediately after children viewed Power Rangers episodes (Boyatzis et al., 1995). As happened in the Bobo doll experiment, children often precisely imitated the model’s violent acts—in this case, flying karate kicks.

- Prolonged exposure to violence desensitizes viewers. It fosters indifference. After spending three evenings watching sexually violent movies, men became less and less bothered by the rapes and slashings shown. Compared with others in a control group, the film watchers later expressed less sympathy for domestic violence victims. And they rated the victims’ injuries as less severe (Mullin & Linz, 1995).

Drawing on such findings, the American Academy of Pediatrics (2009) has advised pediatricians that “media violence can contribute to aggressive behavior, desensitization to violence, nightmares, and fear of being harmed.”

189