Studying Memory

7-1 What is memory, and how do information-processing models help us study memory?

Be thankful for memory—your storehouse of accumulated learning. Your memory enables you to recognize family, speak your language, find your way home, and locate food and water. Your memory enables you to enjoy an experience and then mentally replay it and enjoy it again. Without memory there would be no savoring of past achievements, no guilt or anger over painful past events. You would instead live in an endless present, each moment fresh. Each person would be a stranger, every language foreign, every task—dressing, cooking, biking—a new challenge. You would even be a stranger to yourself, lacking that ongoing sense of self that extends from your distant past to your momentary present.

Be thankful for memory—your storehouse of accumulated learning. Your memory enables you to recognize family, speak your language, find your way home, and locate food and water. Your memory enables you to enjoy an experience and then mentally replay it and enjoy it again. Without memory there would be no savoring of past achievements, no guilt or anger over painful past events. You would instead live in an endless present, each moment fresh. Each person would be a stranger, every language foreign, every task—dressing, cooking, biking—a new challenge. You would even be a stranger to yourself, lacking that ongoing sense of self that extends from your distant past to your momentary present.

Earlier, in the Sensation and Perception chapter, we considered one of psychology’s big questions: How does the world out there enter your brain? In this chapter we consider a related question: How does your brain pluck information out of the world around you and store it for a lifetime of use? Said simply, how does your brain construct your memories?

To help clients imagine future buildings, architects create miniature models. Similarly, psychologists create models of memory to help us think about how our brain forms and retrieves memories. One such model, known as the information-processing model, compares human memory to a computer’s operation. It assumes that, to remember something, we must

- get information into our brain, a process called encoding.

- retain that information, a process called storage.

- later get the information back out, a process called retrieval.

Let’s take a closer look.

An Information-Processing Model

7-2 What is the three-stage information-processing model, and how has later research updated this model?

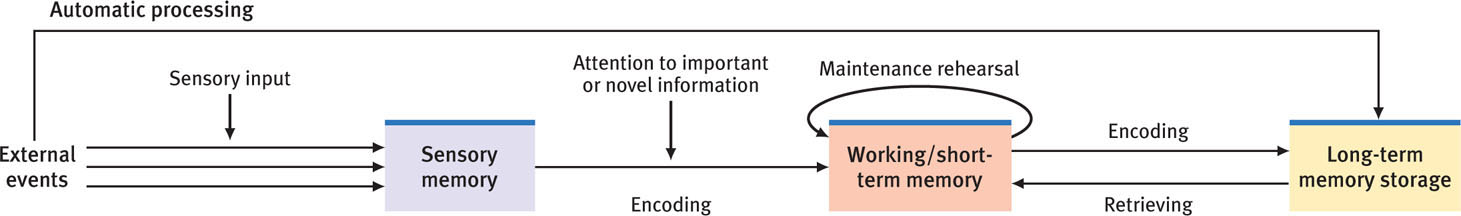

Richard Atkinson and Richard Shiffrin (1968) proposed that we form memories in three stages.

- We first record to-be-remembered information as a fleeting sensory memory.

- From there, we process information into short-term memory, where we encode it through rehearsal.

- Finally, information moves into long-term memory for later retrieval.

Other psychologists later updated this model to include important newer concepts, including working memory and automatic processing (FIGURE 7.1).

Working Memory

So much active processing takes place in the middle stage that psychologists now prefer the term working memory. In Atkinson and Shiffrin’s original model, the second stage appeared to be a temporary shelf for holding recent thoughts and experiences. We now know that this working-memory stage is more like an active desktop—where your brain processes important information, making sense of new input and linking it with long-term memories. When you process verbal information, your active working memory connects new information to what you already know or imagine (Cowan, 2010; Kail & Hall, 2001). If you hear someone say eye-screem, you may encode it as “ice cream” or “I scream,” depending on both the context (snack shop or horror film) and your experience.

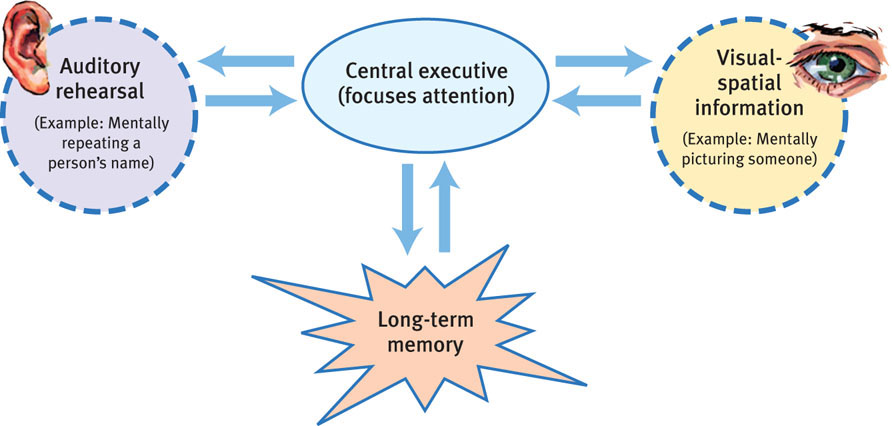

The information you are now reading may enter your working memory through vision. You may also silently repeat the information using auditory rehearsal. Integrating these memory inputs with your existing long-term memory requires focused attention. Alan Baddeley (2002) suggested a central executive handles this focused processing (FIGURE 7.2).

Without focused attention, information often fades. In one experiment, people read and typed new information they would later need, such as “An ostrich’s eye is bigger than its brain.” If they knew the information would be available online, they invested less energy in remembering it, and they remembered it less well (Sparrow et al., 2011).

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 7.1

What two new concepts update the classic Atkinson-Shiffrin three-stage information-processing model?

What two new concepts update the classic Atkinson-Shiffrin three-stage information-processing model?

(1) We form some memories through automatic processing, without our awareness. The Atkinson-Shiffrin model focused only on conscious memories. (2) The newer concept of a working memory emphasizes the active processing that we now know takes place in Atkinson-Shiffrin’s short-term memory stage.

Question 7.2

What are two basic functions of working memory?

What are two basic functions of working memory?

(1) Active processing of incoming visual and auditory information, and (2) focusing our spotlight of attention.