Retrieval: Getting Information Out

Remembering an event requires more than getting information into our brain and storing it there. To use that information, we must retrieve it. How do psychologists test whether learning has been retained over time? What triggers retrieval?

Remembering an event requires more than getting information into our brain and storing it there. To use that information, we must retrieve it. How do psychologists test whether learning has been retained over time? What triggers retrieval?

Measuring Retention

7-14 How do psychologists assess memory with recall, recognition, and relearning?

Memory is learning that persists over time. Three types of evidence indicate whether something has been learned and retained:

- Recall—drawing information out of storage and into your conscious awareness. Example: a fill-in-the-blank question.

- Recognition—identifying items you previously learned. Example: a multiple-choice question.

- Relearning—learning something more quickly when you learn it a second or later time. Example: Reviewing the first weeks of coursework to prepare for your final exam, you will relearn the material more easily than you did originally.

Long after you cannot recall most of your high school classmates, you may still be able to recognize their yearbook pictures in a photo lineup and spot their names in a list of names. One research team found that people who had graduated 25 years earlier could not recall many of their old classmates, but they could recognize 90 percent of their pictures and names (Bahrick et al., 1975).

Our recognition memory is quick and vast. “Is your friend wearing a new or old outfit?” Old. “Is this 5-second movie clip from a film you’ve ever seen?” Yes. “Have you ever before seen this person—this minor variation on normal human features?” No. Before our mouth can form an answer to any of millions of such questions, our mind knows, and knows that it knows.

Speed of relearning also reveals memory. Memory explorer Ebbinghaus showed this long ago by studying his own learning and memory.

Put yourself in Ebbinghaus’ shoes. How could you produce new items to learn? Ebbinghaus’ answer was to form a list of all possible nonsense syllables by sandwiching a vowel between two consonants. Then, for a particular experiment, he would randomly select a sample of the syllables, practice them, and test himself. To get a feel for his experiments, rapidly read aloud the following list, repeating it eight times (from Baddeley, 1982). Then, without looking, try to recall the items:

JIH, BAZ, FUB, YOX, SUJ, XIR, DAX, LEQ, VUM, PID, KEL, WAV, TUV, ZOF, GEK, HIW.

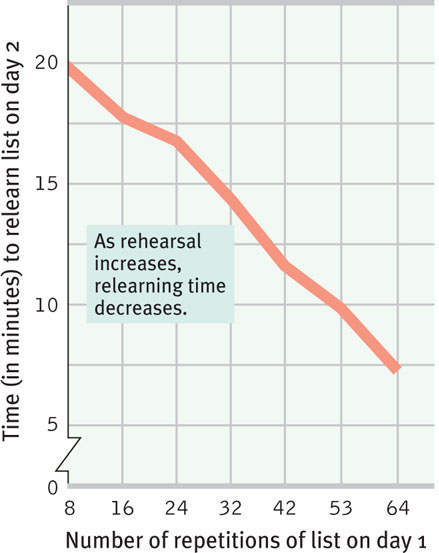

The day after learning such a list, Ebbinghaus recalled only a few of the syllables. But were they entirely forgotten? No. The more often he practiced the list aloud on day 1, the fewer times he would have to practice it to relearn it on day 2 (FIGURE 7.9).

The point to remember: Tests of recognition and of time spent relearning demonstrate that we remember more than we can recall.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 7.10

Multiple-choice questions test our

Multiple-choice questions test our

|

b

Question 7.11

Fill-in-the blank questions test our ______.

Fill-in-the blank questions test our ______.

recall

Question 7.12

If you want to be sure to remember what you’re learning for an upcoming test, would it be better to use recall or recognition to check your memory? Why?

If you want to be sure to remember what you’re learning for an upcoming test, would it be better to use recall or recognition to check your memory? Why?

It would be better to test your memory with recall (such as with short-answer or fill-in-the-blank self-test questions) rather than recognition (such as with multiple-choice questions). Recalling information is harder than recognizing it. So if you can recall it, that means your retention of the material is better than if you could only recognize it. Your chances of test success are therefore greater.

Retrieval Cues

7-15 How do external events, internal moods, and order of appearance affect memory retrieval?

Imagine a spider suspended in the middle of her web, held up by the many strands extending outward from her in all directions to different points. You could begin at any one of these anchor points and follow the attached strand to the spider.

Retrieving a memory is similar. Memories are held in storage by a web of associations, each piece of information connected to many others. Suppose you encode into your memory the name of the person sitting next to you in class. With that name, you will also encode other bits of information, such as your surroundings, mood, seating position, and so on. These bits serve as retrieval cues, anchor points for pathways you can follow to access your classmate’s name when you need to recall it later. The more retrieval cues you’ve encoded, the better your chances of finding a path to the memory suspended in this web of information.

Priming

The best retrieval cues come from associations you form at the time you encode a memory—smells, tastes, and sights that can call up your memory of the associated person or event. When trying to recall something, you may mentally place yourself in the original context. For most of us, that includes visual information. After losing his sight, British scholar John Hull (1990, p. 174) described his difficulty recalling such details:

I knew I had been somewhere, and had done particular things with certain people, but where? I could not put the conversations…into a context. There was no background, no features against which to identify the place. Normally, the memories of people you have spoken to during the day are stored in frames which include the background.

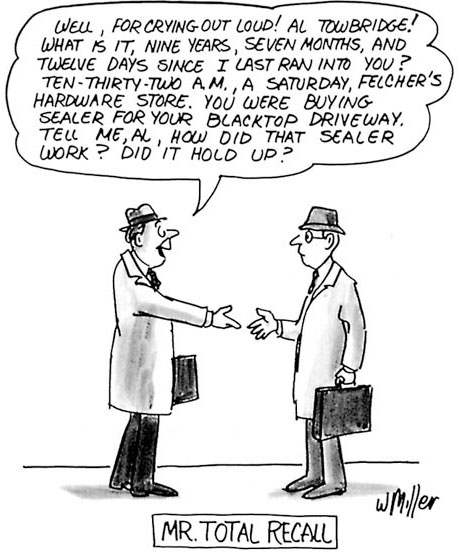

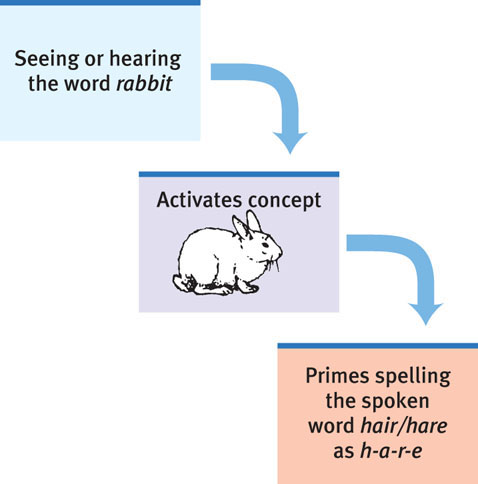

Often associations are activated without your awareness. Seeing or hearing the word rabbit can activate associations with hare, even though you may not recall having seen or heard rabbit (FIGURE 7.10). Although this process, called priming, happens without your conscious awareness, it can influence your attitudes and your behavior.

Want to impress your friends with your new knowledge? Ask them two rapid-fire questions:

- How do you pronounce the word spelled by the letters s-h-o-p?

- What do you do when you come to a green light?

If they answer stop to the second question, you have demonstrated priming.

Context Effects

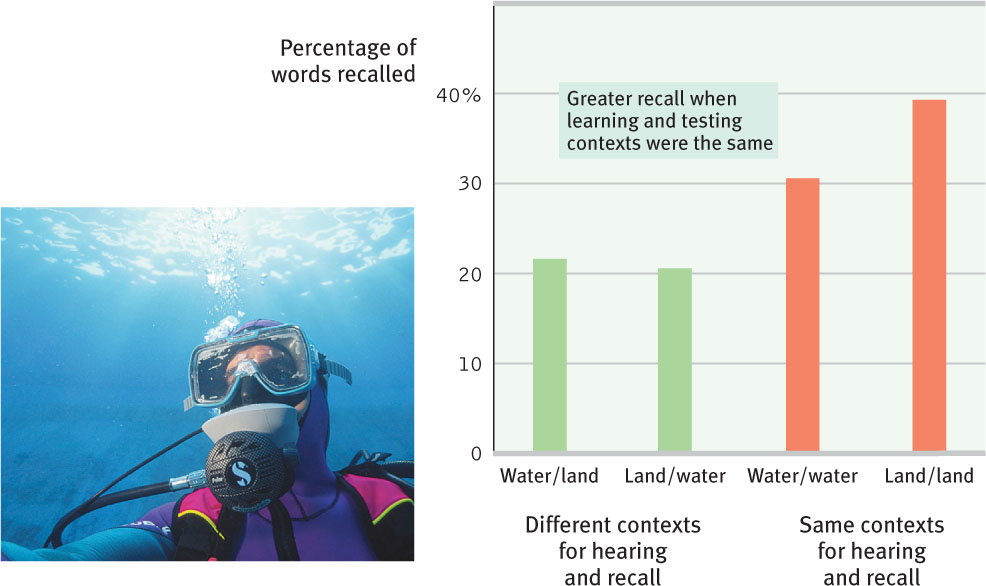

To prime your memory of something, it may help to return to the context where you experienced it. In one study, scuba divers listened to a list of words in two different settings, either 10 feet underwater or sitting on the beach (Godden & Baddeley, 1975). Later, the divers recalled more words when they were retested in the same place (FIGURE 7.11).

You may have experienced similar context effects. Imagine this: While taking notes from this book, you realize you need to sharpen your pencil. You get up and walk to another room, but then you cannot remember why. After you return to your desk, it hits you: “I wanted to sharpen this pencil!” What happens to create this frustrating experience? In one context (desk, reading psychology), you realize your pencil needs sharpening. When you go to the other room and are in a different context, you have few cues to lead you back to that thought. But back at your desk, you are once again in the context in which you encoded the thought (“This pencil is dull.”).

State-Dependent Memory

State-dependent memory is closely related to context-dependent memory. What we learn in one state—be it drunk or sober—may be more easily recalled when we are again in that state. What people learn when drunk they don’t recall well in any state (alcohol disrupts storage). But they recall it slightly better when again drunk. Someone who hides money when drunk may forget the location until drunk again.

Moods are also states that influence what we remember. Being happy primes sweet memories. Being angry or depressed primes sour ones. Say you have a terrible evening. Your date canceled, you lost your phone, and now a new red sweatshirt somehow made its way into your white laundry batch. Your bad mood may trigger other unhappy memories. If a friend or family member walks in at this point, your mind may fill with bad memories of that person.

This tendency to recall events that fit our mood is called mood-congruent memory. If put in a great mood—whether under hypnosis or just by the day’s events (a World Cup soccer victory for German participants in one study)—people recall the world through rose-colored glasses (DeSteno et al., 2000; Forgas et al., 1984; Schwarz et al., 1987). They judge themselves competent and effective. They view other people as kind and giving. And they’re sure happy events happen more often than unhappy ones.

Knowing this mood-memory connection, we should not be surprised that in some studies currently depressed people have recalled their parents as rejecting and punishing. Formerly depressed people have described their parents in more positive ways—much as do those who have never been depressed (Lewinsohn & Rosenbaum, 1987; Lewis, 1992). Similarly, adolescents’ ratings of parental warmth in one week have offered few clues to how they would rate their parents six weeks later (Bornstein et al., 1991). When teens were down, their parents seemed inhuman. As moods brightened, those devil parents became angels.

Mood effects on retrieval help explain why our moods persist. When happy, we recall happy events and see the world as a happy place, which prolongs our good mood. When depressed, we recall sad events, which darkens our view of current events. For those predisposed to depression, this process can help maintain a vicious, dark cycle.

Serial Position Effect

Another memory-retrieval quirk, the serial position effect, can leave you wondering why you have large holes in your memory of a list of recent events. Imagine it’s your first day in a new job, and your manager is introducing co-workers. As you meet each person, you silently repeat everyone’s name, starting from the beginning. As the last person smiles and turns away, you hope you’ll be able to greet your new co-workers by name the next day.

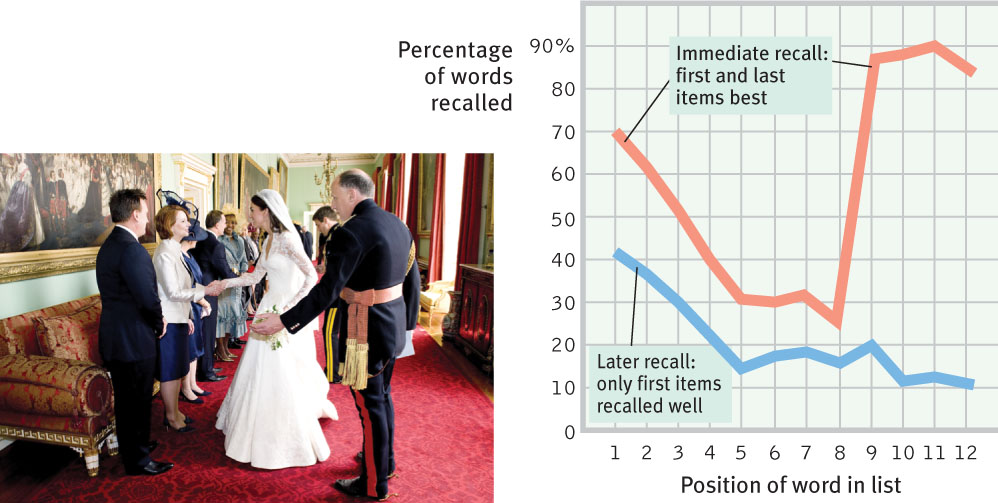

Don’t count on it. Because you have spent more time rehearsing the earlier names than the later ones, those are the names you’ll probably recall more easily the next day. In experiments, when people viewed a list of items (words, names, dates, even odors) and immediately tried to recall them in any order, they fell prey to the serial position effect (Reed, 2000). They briefly recalled the last items especially quickly and well, perhaps because those last items were still in working memory. But after a delay, when they shifted their attention away from the last items, their recall was best for the first items (FIGURE 7.12).

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 7.13

What is priming?

What is priming?

Priming is the activation (often without our awareness) of associations.

Question 7.14

When we are tested immediately after viewing a list of words, we tend to recall the first and last items best, which is known as the ______ _______ effect.

When we are tested immediately after viewing a list of words, we tend to recall the first and last items best, which is known as the ______ _______ effect.

serial position