Motivational Concepts

9-1 What is motivation, and what are three key perspectives that help us understand motivated behaviors?

Our motivations arise from the interplay between nature (the bodily “push”) and nurture (the “pulls” from our personal experiences, thoughts, and culture). Let’s consider three perspectives that psychologists have used to understand motivated behaviors.

Our motivations arise from the interplay between nature (the bodily “push”) and nurture (the “pulls” from our personal experiences, thoughts, and culture). Let’s consider three perspectives that psychologists have used to understand motivated behaviors.

Drive-Reduction Theory

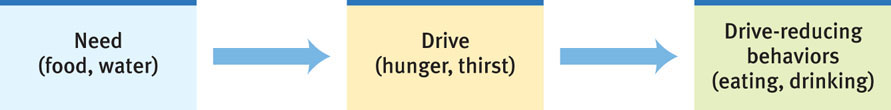

Drive-reduction theory makes three assumptions:

- We have physiological needs, such as the need for food or water.

- If a need is not met, it creates a drive, an aroused, motivated state, such as hunger or thirst.

- That drive pushes us to reduce the need by, say, eating or drinking.

The goal of this three-step process (FIGURE 9.1), from need to drive-reducing behavior, is homeostasis, our body’s natural tendency to maintain a steady internal state. (Homeostasis means “staying the same.”) The body’s heat-regulation system, which works like a room’s thermostat, is an example of homeostasis. Both systems monitor temperature and feed information to a control device. If the room’s temperature cools, the control device switches on the furnace. Likewise, if our body’s temperature cools, our blood vessels narrow to conserve warmth, and we search for warmer clothes or a warmer environment.

We also are pulled by incentives—environmental stimuli that attract or repel us, depending on our individual learning histories. If you are hungry, the aroma of good food will motivate you. Whether that aroma comes from fresh-baked bread or toasted ants will depend on your culture and experience.

When there is both a need and an incentive, we feel strongly driven. Let’s assume you are motivated more by fresh-baked bread than by fresh-toasted ants. You’ve skipped lunch and you can smell bread baking in your friend’s kitchen. You will feel a strong drive to satisfy your hunger, and the baking bread will be a powerful incentive that will motivate your actions.

For each motive, we can therefore ask, “How are we pushed by our inborn bodily needs and pulled by incentives in the environment?”

Arousal Theory

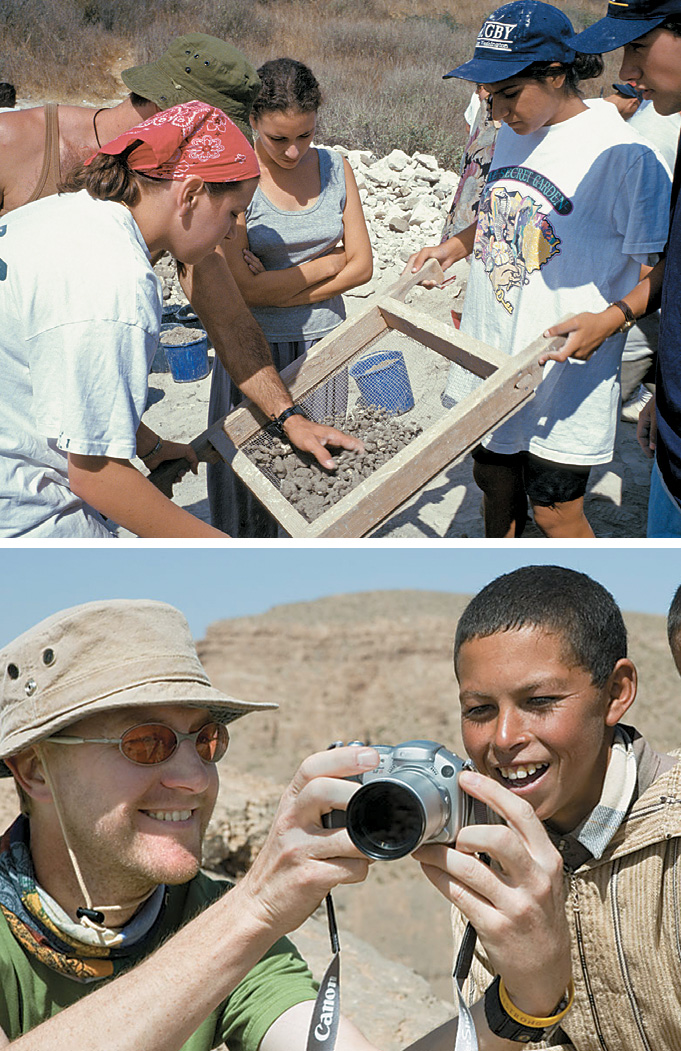

We are much more than homeostatic systems, however. When we are aroused, we are physically energized, or tense. Some motivated behaviors actually increase arousal (FIGURE 9.2). Well-fed animals with no clear, need-based drive will leave a safe shelter to explore and gain information. Curiosity drives monkeys to monkey around trying to figure out how to unlock a latch that opens nothing, or how to open a window that allows them to see outside their room (Butler, 1954). Curiosity drives 9-month-old infants who check out every corner of the house. It drives the scientists whose work this text discusses. And it drives adventurers such as Aron Ralston and George Mallory. Asked why he wanted to climb Mount Everest, the New York Times reported that Mallory answered, “Because it is there.” Those who, like Mallory and Ralston, enjoy high arousal are most likely to enjoy intense music, novel foods, and risky behaviors (Zuckerman, 1979). They are “sensation seekers.”

© David Samuel Robbins/Corbis

We humans hunger for information (Biederman & Vessel, 2006). When we find that all our biological needs have been met, we feel bored and seek stimulation to increase our arousal. But not too much stimulation, for that brings stress and sends us looking for ways to decrease arousal. Arousal theory describes this search for the right arousal level, a search that energizes and directs our behavior.

257

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 9.1

Performance peaks at lower levels of arousal for difficult tasks, and at higher levels for easy or well-learned tasks. (1) How might this phenomenon affect runners? (2) How might this phenomenon affect anxious test-takers facing a difficult exam? (3) How might the performance of anxious students be affected by relaxation training?

(1) Runners tend to excel when aroused by competition. (2) High anxiety in test-takers may disrupt their performance. (3) Teaching anxious students how to relax before an exam can enable them to perform better (Hembree, 1988).

A Hierarchy of Needs

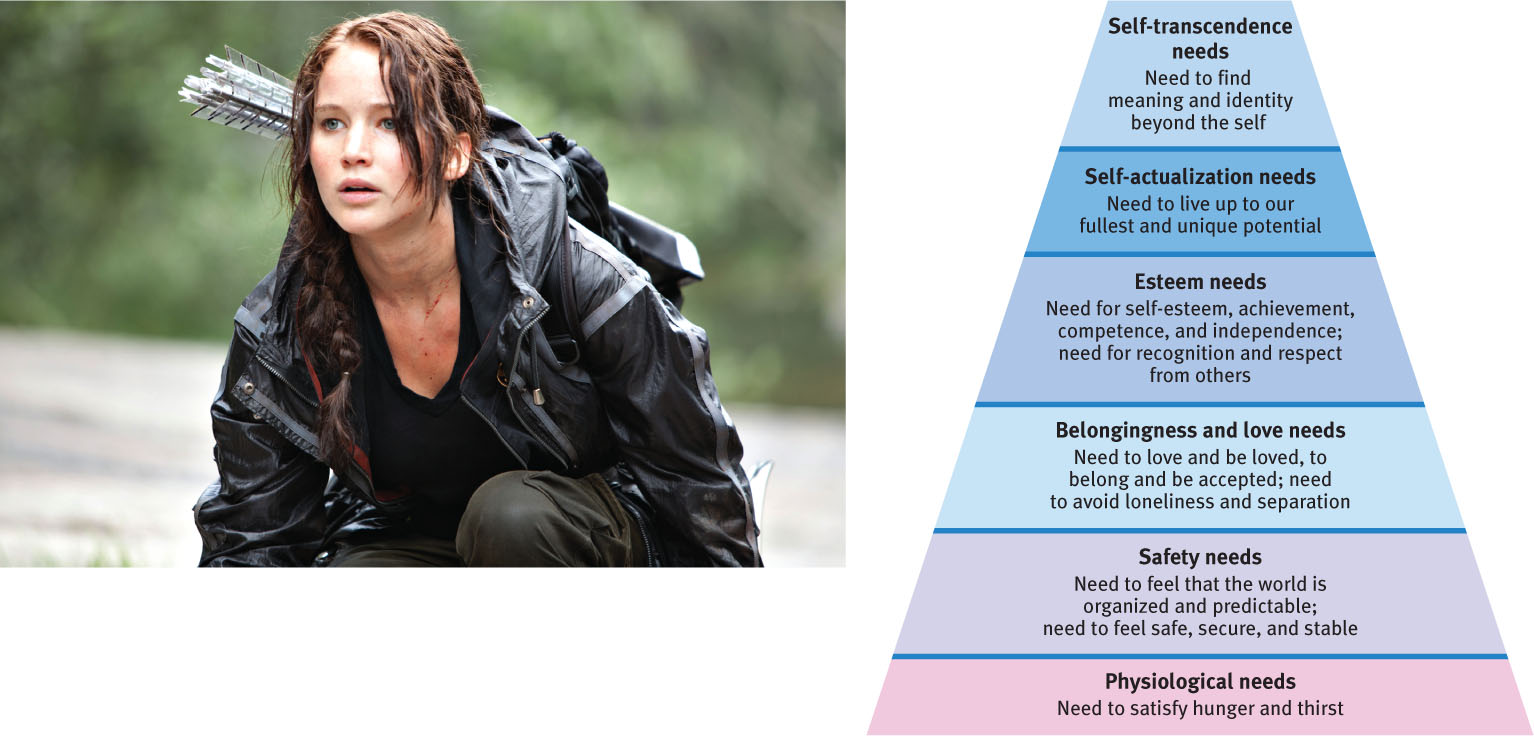

Some needs are more important than others. At this moment, with your needs for air and water satisfied, other motives are directing your behavior. But if you were deprived of water, your thirst would take over your thoughts. Just ask Aron Ralston. Or ask the semistarved people of the fictional Panem, whose districts, represented by a boy and girl selected by lottery, must compete in mortal Hunger Games. Food matters. Yet in Panem, as in our world, we do not live by bread alone. People also have needs for safety, connection, and self-worth.

Abraham Maslow (1970) viewed human motives as a pyramid—a hierarchy of needs (FIGURE 9.3). At the pyramid’s base are physiological needs, such as those for food. If those are unmet, life is a hunger game. Only after these needs are met, said Maslow (1971), do we try to meet our need for safety, and then to satisfy our needs to give and receive love and to enjoy self-esteem. At the peak of the pyramid are the highest human needs. At the self-actualization level, people seek to realize their own potential. At the very top is self-transcendence, which Maslow proposed near the end of his life. At this level, some people strive for meaning, purpose, and identity that is transpersonal—beyond (trans) the self (Koltko-Rivera, 2006).

There are exceptions to Maslow’s hierarchy. For example, people have starved themselves to make a political statement. Nevertheless, some needs are indeed more basic than others. In poorer nations, money—and the food and shelter it buys—more strongly commands attention and predicts feelings of well-being. In wealthy nations, where most are able to meet their basic needs, home-life satisfaction is a better predictor of well-being (Oishi et al., 1999).

258

Let’s take a closer look now at two specific motives: the basic-level motive, hunger, and the higher-level need to belong. As you read about these motives, watch for ways that incentives (the psychological “pull”) interact with bodily needs (the biological “push”).

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 9.2

How do drive-reduction theory and arousal theory contribute to our understanding of motivated behavior?

From drive-reduction theory, we know that our physiological needs (such as hunger) create an aroused state that drives us to reduce the need (for example, by eating). Arousal theory suggests we need to maintain an optimal level of arousal, which helps explain our motivation toward behaviors that meet no physiological need.

Question 9.3

After hours of driving alone in an unfamiliar city, you finally see a diner. Although it looks deserted and a little creepy, you stop because you are really hungry. How would Maslow’s hierarchy of needs explain your behavior?

According to Maslow, our drives to meet the physiological needs of hunger and thirst take priority over safety needs, prompting us to take risks at times in order to eat.