The Need to Belong

9-5 What evidence points to our human need to belong?

Imagine yourself like the fictional Robinson Crusoe, dropped on an island…alone…for the rest of your life. Food, shelter, and comfort are yours—but there are no fellow humans, no social media, no story but your own. Do you savor the stressless serenity?

Imagine yourself like the fictional Robinson Crusoe, dropped on an island…alone…for the rest of your life. Food, shelter, and comfort are yours—but there are no fellow humans, no social media, no story but your own. Do you savor the stressless serenity?

Surely not. We are what Greek philosopher Aristotle called the social animal. Cut off from friends or family—alone in prison or in a new school or in a foreign land—most people feel keenly their lost connections with important others. This deep need to belong seems a basic human motivation (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Josh Silverman (2008), president of Internet communication company Skype, understood the need to belong: “There’s no question in my mind about what stands at the heart of the communication revolution—the human desire to connect.” And connect we do.

The Benefits of Belonging

Social bonds boosted our ancestors’ chances of survival. These bonds helped keep children close to their caregivers, protecting them from many threats. As adults, those who formed attachments were more likely to reproduce and co-nurture their offspring to maturity. To be “wretched” literally means, in its Middle English origin (wrecche), to be without kin nearby.

Survival also was supported by cooperation. In solo combat, our ancestors were not the toughest predators. But as hunters, they learned that eight hands were better than two. As food gatherers, they gained protection from their enemies by traveling in groups. Those who felt a need to belong survived and reproduced most successfully, and their genes now rule.

264

People in every society on Earth belong to groups (and, as Chapter 12 explains, prefer and favor “us” over “them”). With the need to belong satisfied by close, supportive relationships, we feel included, accepted, and loved, and our self-esteem rides high. Indeed, self-esteem is a measure of how valued and accepted we feel (Leary et al., 1998). When our need for relatedness is satisfied in balance with two other basic psychological needs—autonomy (a sense of personal control) and competence—the result is a deep sense of well-being (Deci & Ryan, 2002; Patrick et al., 2007; Sheldon & Niemiec, 2006). To feel free, capable, and connected is to enjoy a good life.

C L O S E - U P

Waist Management

Perhaps you are shaking your head: “Slim chance I have of becoming and staying thin.” People struggling with obesity should seek medical evaluation and guidance. For others who wish to take off a few pounds, researchers have offered these tips.

Begin only if you feel motivated and self-disciplined. For most people, permanent weight loss means making a career of staying thin. It requires a lifelong change in eating habits, combined with increased exercise.

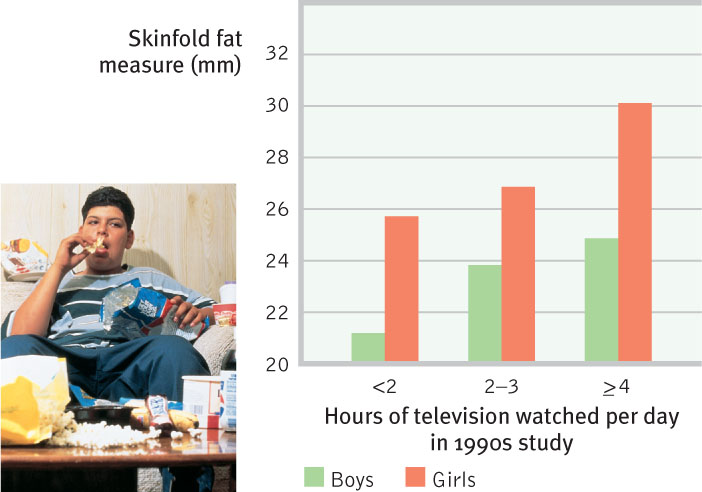

Exercise and get enough sleep. Inactive people are often overweight (FIGURE 9.10). Especially when supported by 7 to 8 nightly hours of sleep, exercise empties fat cells, builds muscle, speeds up metabolism, and helps lower your settling point (Bennett, 1995; Kolata, 1987; Thompson et al., 1982).

Minimize exposure to tempting food cues. Food shop only on a full stomach. Keep tempting foods out of the house or out of sight.

Limit variety and eat healthy foods. Given more variety, people consume more; so, eat simple meals with whole grains, fruits, and vegetables. Healthy fats, such as those found in olive oil and fish, help regulate appetite and artery-clogging cholesterol (Taubes, 2001, 2002). Better crispy greens than Krispy Kremes.

Reduce portion sizes. Serve food with smaller bowls, plates, and utensils.

Don’t starve all day and eat one big meal at night. This pattern, common among overweight people, slows metabolism. By late morning, most of us are more alert and less fatigued if we have eaten a balanced breakfast (Spring et al., 1992).

Beware of the binge. Especially for men, eating slowly can lead to eating less (Martin et al., 2007). Even when people consciously control their eating, drinking alcohol or feeling anxious or depressed can unleash the urge to overeat (Herman & Polivy, 1980).

Before eating with others, decide how much you want to eat. Eating with friends can distract us from monitoring our own eating (Ward & Mann, 2000).

Remember, most people occasionally lapse. A lapse need not become a full collapse.

Connect to a support group. Share your goals and progress by joining others, either face to face or online (Freedman, 2011).

Is it surprising, then, that so much of our social behavior aims to increase our feelings of belonging? To win friendship and avoid rejection, we generally conform to group standards. We monitor our behavior, hoping to make a good impression. We spend billions on clothes, cosmetics, diet, and fitness—all motivated by our search for love and acceptance.

By drawing a sharp circle around “us,” the need to belong feeds both deep attachments and menacing threats. Out of our need to define a “we” come loving families, faithful friendships, and team spirit, but also teen gangs, ethnic rivalries, and fanatic nationalism.

265

For good or for bad, we work hard to form and maintain our relationships. Familiarity breeds liking, not contempt. Thrown together at work, on a hiking trip, in groups at school, we behave like magnets, moving closer, forming bonds. Parting, we feel distress. We promise to call, to write, to come back for reunions.

Even when bad relationships break, people suffer. In one 16-nation survey, and in repeated U.S. surveys, separated and divorced people have been half as likely as married people to say they were “very happy” (Inglehart, 1990; NORC, 2007). Divorce also predicts earlier mortality. In an analysis of 755,000 divorces in 11 different countries, divorce was associated with dying earlier (Sbarra et al., 2011). After such separations, loneliness and anger—and sometimes even a strange desire to be near the former partner—linger. For those in abusive relationships, the fear of being alone sometimes seems worse than the certainty of emotional or physical pain. Children who move through a series of foster homes also know the fear of being alone. After repeated breaks in budding attachments, children may have difficulty forming deep attachments. The evidence is clearest at the extremes—children who grow up in institutions without a sense of belonging to anyone, or who are locked away at home and severely neglected. They become pathetic creatures, withdrawn, frightened, speechless.

No matter how secure our early years were, we all experience anxiety, loneliness, jealousy, or guilt when something threatens or dissolves our social ties. Many of life’s best moments occur when close relationships begin: making a new friend, falling in love, having a baby. And many of life’s worst moments happen when close relationships end (Jaremka et al., 2011). At such times, we may feel life is empty, pointless. For those moving alone to new places, the stress and loneliness can be depressing. After years of placing individual refugee and immigrant families in isolated communities, U.S. agencies today encourage chain migration (Pipher, 2002). The second refugee Sudanese family settling in a town generally has an easier adjustment than the first.

The Pain of Being Shut Out

Sometimes our need to belong is denied. Can you recall a time when you felt excluded or ignored or shunned? Perhaps you were unfriended on a social networking site, ignored in a chat room, or had a text message or e-mail go unanswered. Or perhaps others gave you the silent treatment, avoided you, looked away, mocked you, or shut you out in some other way.

This is ostracism—social exclusion (Williams, 2007, 2009). Worldwide, humans use many forms of ostracism—exile, imprisonment, solitary confinement—to punish, and therefore control, social behavior. For children, even a brief time-out in isolation can be punishing. Among prisoners, half of all suicides occur among those experiencing the extreme exclusion of solitary confinement (Goode, 2012).

Being shunned threatens our need to belong (Williams & Zadro, 2001). Lea, a lifelong victim of the silent treatment by her mother and grandmother, described the effect. “It’s the meanest thing you can do to someone, especially if you know they can’t fight back. I never should have been born.” Like Lea, people often respond to ostracism with depressed moods, efforts to restore their acceptance, and then withdrawal. After two years of silent treatment by his employer, Richard reported, “I came home every night and cried. I lost 25 pounds, had no self-esteem, and felt that I wasn’t worthy.”

266

Rejected and powerless, people may seek new friends. Or they may turn nasty, as did college students made to feel rejected in one series of experiments (Baumeister et al., 2002; Twenge et al., 2001, 2002, 2007). Some students were told that a personality test they had taken showed that they were “the type likely to end up alone later in life.” Others heard that people they had met didn’t want them in a group that was forming. Still others heard good news. These lucky people would have “rewarding relationships throughout life,” or “everyone chose you as someone they’d like to work with.” How did students react after being told they weren’t wanted or would end up alone? They were much more likely to engage in self-defeating behaviors and to underperform on aptitude tests. When later interacting with those who had excluded them, they also were more likely to act in mean or aggressive ways (blasting people with noise, for example). “If intelligent, well-adjusted, successful…students can turn aggressive in response to a small laboratory experience of social exclusion,” noted the research team, “it is disturbing to imagine the aggressive tendencies that might arise from…chronic exclusion from desired groups in actual social life.” (At the end of the experiments, the study was fully explained and the participants left feeling reassured.)

Ostracism is a real pain. Brain scans show increased activity in areas that also activate in response to physical pain (Kross et al., 2011; Eisenberger, 2012a,b). That helps explain another surprising finding. Acetaminophen, found in such products as Tylenol and Anacin, and taken to relieve physical pain, also lessens social pain (DeWall et al., 2010). Psychologically, we seem to experience social pain with the same emotional unpleasantness that marks physical pain. And across cultures, we use the same words (for example, hurt, crushed) for social pain and physical pain (MacDonald & Leary, 2005).

The opposite of ostracism—feelings of love—activate brain areas associated with rewards and satisfaction. Loved ones activate a brain region that dampens feelings of physical pain (Eisenberger et al., 2011). In one experiment, university students felt markedly less pain when looking at their beloved’s picture, rather than at someone else’s photo (Younger et al., 2010).

The bottom line: Social isolation and rejection foster depressed moods or emotional numbness, and they can trigger aggression (Baumeister et al., 2009; Gerber & Wheeler, 2009). They can put us at risk for mental decline and ill health (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2009). But love is a natural painkiller. When feelings of acceptance and connection build, so do self-esteem, positive feelings, and the desire to help rather than hurt others (Buckley & Leary, 2001).

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 9.7

How have students reacted in studies where they were made to feel rejected and unwanted? What helps explain these results?

These students’ basic need to belong seems to have been disrupted. They engaged in more self-defeating behaviors, underperformed on aptitude tests, and displayed less empathy and more aggression.

Connecting and Social Networking

9-6 How does social networking influence us?

As social creatures, we live for connection. Researcher George Vaillant (2009) was asked what he had learned from studying 238 Harvard University men from the 1930s to the end of their lives. He replied, “The only thing that really matters in life are your relationships to other people.” A South African Zulu saying captures the idea: Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu—“a person is a person through other persons.”

Mobile Networks and Social Media

Look around and see humans connecting: talking, texting, posting, chatting, social gaming, e-mailing. The changes in how we connect have been fast and vast.

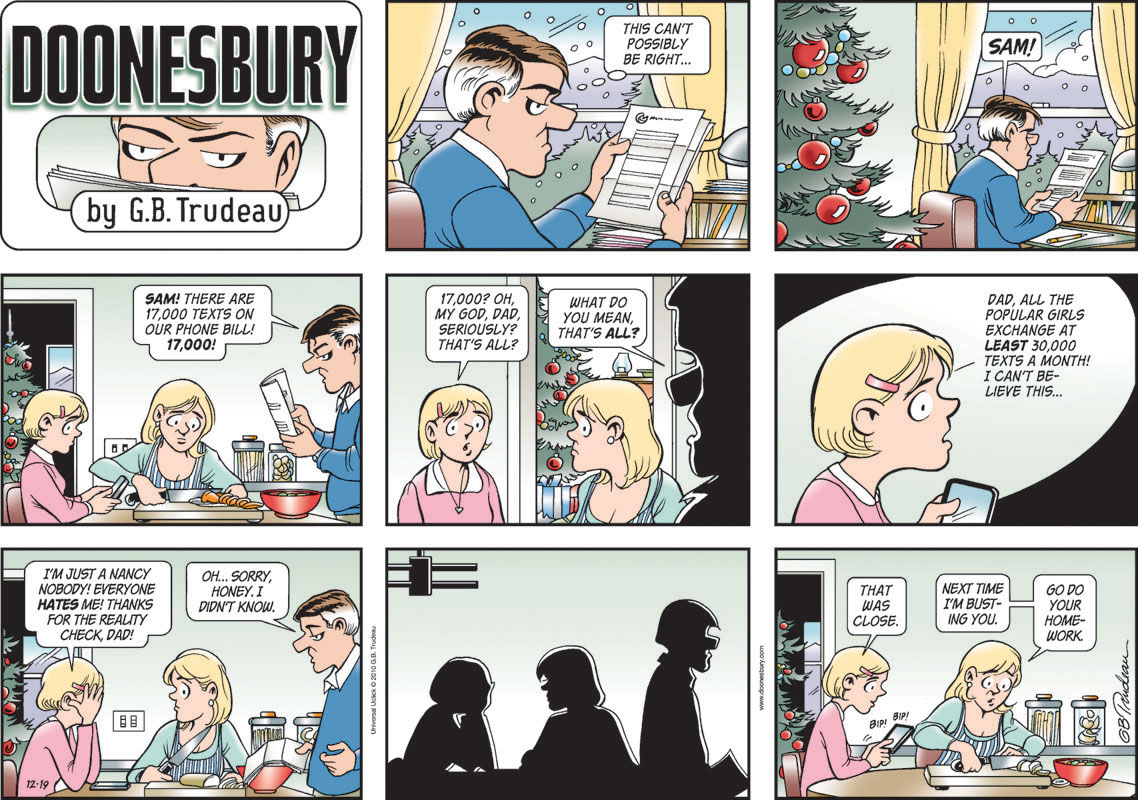

- At the end of 2013, the world had 7.1 billion people and 6.8 billion mobile cell-phone subscriptions (ITU, 2013). But phone talking now accounts for less than half of U.S. mobile network traffic (Wortham, 2010). In Canada and elsewhere, e-mailing is being displaced by texting, Facebook, and other messaging technology (IPSOS, 2010a). Speedy texting is not really writing, said one observer (McWhorter, 2012), but rather a new form of conversation—“fingered speech.”

- Three in four U.S. teens text. Half (mostly females) send 60 or more texts daily (Lenhart, 2012). For many, it’s as though friends, for better or worse, are always present.

- How many of us are using social networking sites, such as Facebook or Twitter? Among 2010’s entering American collegians, 94 percent were (Pryor et al., 2011). With a “critical mass” of your friends on a social network, its lure becomes hard to resist. Such is our need to belong. Check in or miss out.

The Net Result: Social Effects of Social Networking

By connecting like-minded people, the Internet serves as a social amplifier. In times of social crisis or personal stress, it provides information and supportive connections. It also functions as an online dating matchmaker (more on those topics in Chapter 12). As electronic communication has become part of the “new normal,” researchers have explored how these changes have affected our relationships.

267

HAVE SOCIAL NETWORKING SITES MADE US MORE, OR LESS, SOCIALLY ISOLATED? In the Internet’s early years, online communication in chat rooms and during social games was mostly between strangers. In that period, the adolescents and adults who spent more time online spent less time with friends; as a result, their offline relationships suffered (Kraut et al., 1998; Mesch, 2001; Nie, 2001). Even in more recent times, lonely people have tended to spend greater-than-average time online (Bonetti et al., 2010; Stepanikova et al., 2010). Social networkers have been less likely to know their real-world neighbors and “64 percent less likely than non-Internet users to rely on neighbors for help in caring for themselves or a family member” (Pew, 2009).

But the Internet has also diversified our social networks. (I am now connected to other hearing-technology advocates across the world.) And despite the decrease in neighborliness, social networking is mostly strengthening our connections with people we already know (DiSalvo, 2010; Valkenburg & Peter, 2010). If your social networking helps you connect with friends, stay in touch with extended family, or find support when facing challenges, then you are not alone (Rainie et al., 2011). So social networks connect us. But they can also, as you’ve surely noticed, become a gigantic time-and attention-sucking distraction. If you are like most other students, two days without social networking access would be followed by a glut of online time, much as a two-day food fast would be followed by a period of feasting (Sheldon et al., 2011).

DOES ELECTRONIC COMMUNICATION STIMULATE HEALTHY SELF-DISCLOSURE? Self-disclosure is sharing ourselves—our joys, worries, and weaknesses—with others. As we will see in Chapter 10, confiding in others can be a healthy way of coping with day-to-day challenges. When communicating electronically rather than face to face, we often are less focused on others’ reactions. We are less self-conscious and thus less inhibited. Sometimes this is taken to an extreme, as when teens send photos of themselves they later regret, or cyberbullies hound a victim, or hate groups post messages promoting bigotry or crimes. More often, however, the increased self-disclosure serves to deepen friendships (Valkenburg & Peter, 2010).

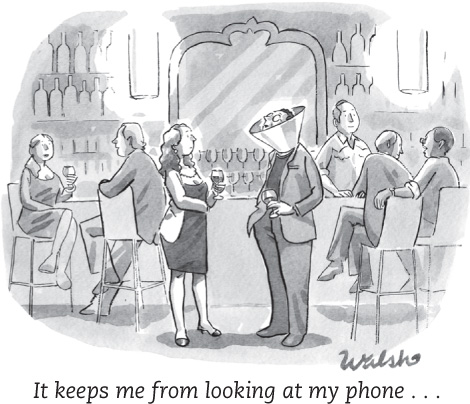

Although electronic networking pays dividends, nature has designed us for face-to-face communication, which appears to be a better predictor of life satisfaction (Killingsworth & Gilbert, 2010; Lee et al., 2011). Texting and e-mailing are rewarding, but eye-to-eye conversation with family and friends is even more so.

DO SOCIAL NETWORKING PROFILES AND POSTS REFLECT PEOPLE’S ACTUAL PERSONALITIES? We’ve all heard stories of Internet predators hiding behind false personalities, values, and motives. Generally, however, social networks reveal a person’s real personality. In one study, participants completed a personality test twice. In one test, they described their “actual personality”; in the other, they described their “ideal self.” Other volunteers then used the participants’ Facebook profiles to create an independent set of personality ratings. The Facebook-profile ratings were much closer to the participants’ actual personalities than to their ideal personalities (Back et al., 2010). In another study, people who seemed most likable on their Facebook page also seemed most likable in face-to-face meetings (Weisbuch et al., 2009). Your online profiles may indeed reflect the real you!

268

DOES SOCIAL NETWORKING PROMOTE NARCISSISM? Narcissism is self-esteem gone wild. Narcissistic people are self-important, self-focused, and self-promoting. Some personality tests assess narcissism with items such as “I like to be the center of attention.” People with high narcissism test scores are especially active on social networking sites. They collect more superficial “friends.” They offer more staged, glamorous photos. And, not surprisingly, they seem more narcissistic to strangers viewing their pages (Buffardi & Campbell, 2008).

For narcissists, social networking sites are more than a gathering place; they are a feeding trough. In one study, college students were randomly assigned either to edit and explain their online profiles for 15 minutes, or to use that time to study and explain a Google Maps routing (Freeman & Twenge, 2010). After completing their tasks, all were tested. Who then scored higher on a narcissism measure? Those who had spent the time focused on themselves.

Maintaining Balance and Focus

In both Taiwan and the United States, excessive online socializing and gaming have been associated with lower grades (Chen & Fu, 2008; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2010). In one U.S. survey, 47 percent of the heaviest users of the Internet and other media were receiving mostly C grades or lower, as were 23 percent of the lightest users (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2010). Except when sleeping, the heaviest users may be almost constantly connected.

In today’s world, each of us is challenged to maintain a healthy balance between our real-world time with family and friends and our online sharing. Experts offer some practical suggestions for balancing online connecting and real-world responsibilities.

- Monitor your time. Keep a log of how you use your time. Then ask yourself, “Does my time use reflect my priorities? Am I spending more or less time online than I intended? Is my time online interfering with school or work performance? Have family or friends commented on this?”

- Monitor your feelings. Ask yourself, “Am I emotionally distracted by my online interests? When I disconnect and move to another activity, how do I feel?”

- “Hide” your more distracting online friends. And in your own postings, practice the golden rule. Before you post, ask yourself, “Is this something I’d care about reading if someone else posted it?”

- Try turning off your mobile devices or leaving them elsewhere. Selective attention—the flashlight of your mind—can be in only one place at a time. When we try to do two things at once, we don’t do either one of them very well (Willingham, 2010). If you want to study or work productively, resist the temptation to check for messages, posts, or e-mails. Disable sound alerts and pop-ups, which can hijack your attention just when you’ve managed to get focused. (I am proofing and editing this chapter in a coffee shop, where I escape the distractions of my computer and office phone.)

- Try a social networking fast (give it up for an hour, a day, or a week) or a time-controlled social media diet (check in only after homework is done, or only during a lunch break). Take notes on what you’re losing and gaining on your new “diet.”

- Refocus by taking a nature walk. People learn better after a peaceful walk in the woods, which—unlike a walk on a busy street—refreshes our capacity for focused attention (Berman et al., 2008).

As psychologist Steven Pinker (2010) said, “The solution is not to bemoan technology but to develop strategies of self-control, as we do with every other temptation in life.”

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 9.8

Social networking tends to ____________ (strengthen/weaken) your relationships with people you already know, ____________ (increase/decrease) your self-disclosure, and ____________ (reveal/hide) your true personality.

strengthen; increase; reveal