Emotion: Arousal, Behavior, and Cognition

9-7 What are the three parts of an emotion, and what theories help us to understand our emotions?

Motivated behavior is often connected to powerful emotions. My own need to belong was unforgettably challenged one day when I went to a huge store to drop off film and brought along Peter, my toddler first-born child. As I set Peter down on his feet and prepared to complete the paperwork, a passerby warned, “You’d better be careful or you’ll lose that boy!” Not more than a few breaths later, after dropping the film in the slot, I turned and found no Peter beside me.

Motivated behavior is often connected to powerful emotions. My own need to belong was unforgettably challenged one day when I went to a huge store to drop off film and brought along Peter, my toddler first-born child. As I set Peter down on his feet and prepared to complete the paperwork, a passerby warned, “You’d better be careful or you’ll lose that boy!” Not more than a few breaths later, after dropping the film in the slot, I turned and found no Peter beside me.

With mild anxiety, I peered around one end of the counter. No Peter in sight. With slightly more anxiety, I peered around the other end. No Peter there, either. Now, with my heart pounding, I circled the neighboring counters. Still no Peter anywhere. As anxiety turned to panic, I began racing up and down the store aisles. He was nowhere to be found. Seeing my alarm, the store manager used the public-address system to ask customers to assist in looking for a missing child. Soon after, I passed the customer who had warned me. “I told you that you were going to lose him!” he now scorned. With visions of kidnapping (strangers routinely admired that beautiful child), I braced for the possibility that my neglect had caused me to lose what I loved above all else, and—dread of all dreads—that I might have to return home and face my wife without our only child. Never before or since have I felt such panic.

269

But then, as I passed the customer service counter yet again, there he was, having been found and returned by some obliging customer! In an instant, the arousal of terror spilled into ecstasy. Clutching my son, with tears suddenly flowing, I found myself unable to speak my thanks and stumbled out of the store awash in grateful joy.

Where do such emotions come from? Why do we have them? What are they made of? Emotions don’t exist just to give us interesting experiences. They are our body’s adaptive response, supporting our survival. When we face challenges, emotions focus our attention and energize our action (Cyders & Smith, 2008). Our heart races. Our pace quickens. All our senses go on high alert. Receiving unexpected good news, we may find our eyes tearing up. We raise our hands in triumph. We feel joy and a newfound confidence.

As my panicked search for Peter illustrates, emotions are a mix of

- bodily arousal (heart pounding).

- expressive behaviors (quickened pace).

- conscious experience including thoughts (“Is this a kidnapping?”) and feelings (fear, panic, joy).

Psychologists’ task is fitting these three pieces together. To do that, we need answers to two big questions:

- A chicken-and-egg debate: Does your bodily arousal come before or after your emotional feelings? (Did I first notice my racing heart and faster step, and then feel terror about losing Peter? Or did my sense of fear come first, stirring my heart and legs to respond?)

- How do thinking (cognition) and feeling interact? Does cognition always come before emotion? (Did I think about a kidnapping threat before I reacted emotionally?)

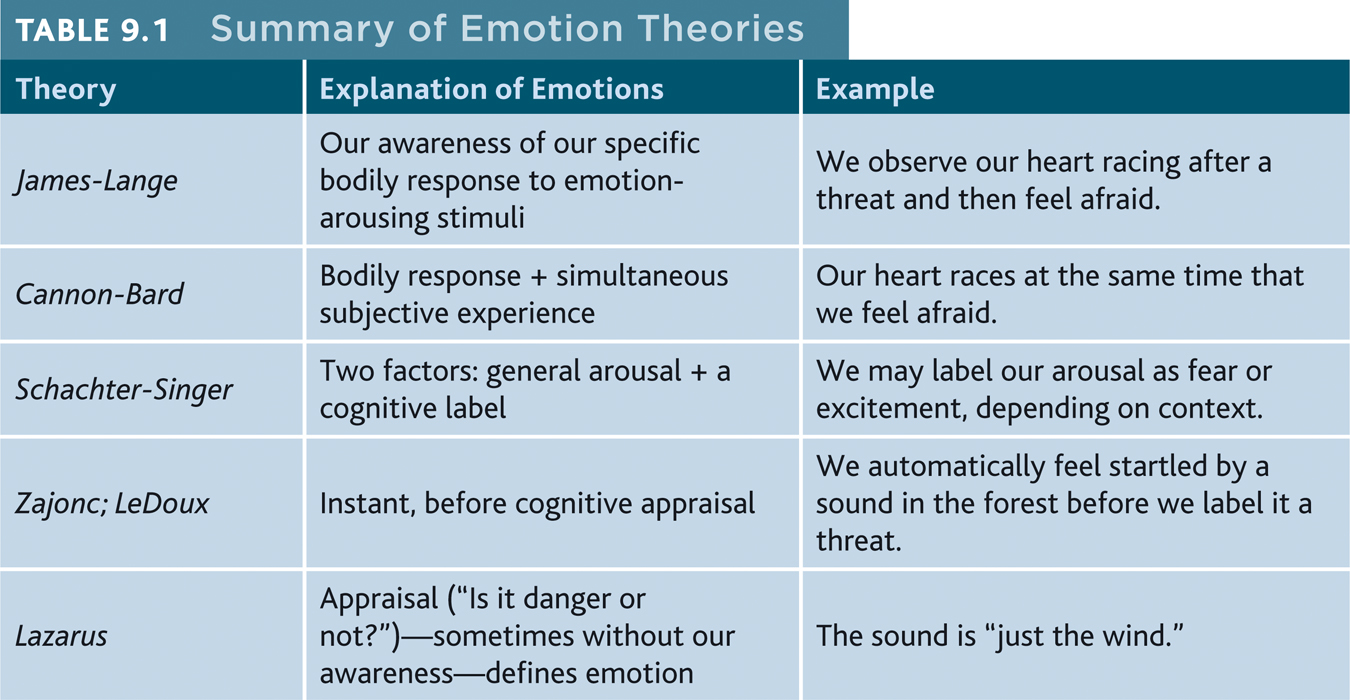

Historic theories of emotion, as well as current research, have tried to answer these questions.

Historic Emotion Theories

James-Lange Theory: Arousal Comes Before Emotion

Common sense tells most of us that we cry because we are sad, lash out because we are angry, tremble because we are afraid. First comes conscious awareness, then the feeling. But to pioneering psychologist William James, this commonsense view of emotion had things backward. Rather, “We feel sorry because we cry, angry because we strike, afraid because we tremble” (1890, p. 1066). James’ idea was also proposed by Danish physiologist Carl Lange, and so is called the James-Lange theory. James and Lange might have guessed that I noticed my racing heart and then, shaking with fright, felt the whoosh of emotion—that my feeling of fear followed my body’s response.

Cannon-Bard Theory: Arousal and Emotion Happen at the Same Time

Physiologist Walter Cannon (1871–1945) disagreed with James and Lange. Does a racing heart signal fear, anger, or love? The body’s responses—heart rate, perspiration, and body temperature—are too similar to cause the different emotions, said Cannon. He and another physiologist, Philip Bard, concluded that our bodily arousal and emotional experience occur together. So, according to the Cannon-Bard theory, my heart began pounding as I experienced fear. The emotion-triggering stimulus traveled to my sympathetic nervous system, causing my body’s arousal. At the same time, it traveled to my brain’s cortex, causing my awareness of my emotion. My pounding heart did not cause my feeling of fear, nor did my feeling of fear cause my pounding heart. Bodily responses and experienced emotions are separate.

270

The Cannon-Bard theory has been challenged by studies of people with severed spinal cords, including a survey of 25 injured World War II soldiers (Hohmann, 1966). Those with lower-spine injuries, who had lost sensation only in their legs, reported little change in their emotions’ intensity. Those with high spinal cord injuries, who could feel nothing below the neck, did report changes. Some reactions were much less intense than before the injuries. Anger, one man confessed, “just doesn’t have the heat to it that it used to. It’s a mental kind of anger.” Other emotions, those expressed mostly in body areas above the neck, were felt more intensely. These men reported increases in weeping, lumps in the throat, and getting choked up when saying good-bye, worshipping, or watching a touching movie. Such evidence has led some researchers to view feelings as “mostly shadows” of our bodily responses and behaviors (Damasio, 2003).

But most researchers now agree that our emotions also involve cognition (Averill, 1993; Barrett, 2006). Whether we fear the man behind us on the dark street depends entirely on whether we interpret his actions as threatening or friendly.

Schachter-Singer Two-Factor Theory: Arousal + Label = Emotion

Stanley Schachter and Jerome Singer (1962) proposed a third theory: Our physical reactions and our thoughts (perceptions, memories, and interpretations) together create emotion. In their two-factor theory, emotions therefore have two ingredients: physical arousal and cognitive appraisal. In their view, an emotional experience requires a conscious interpretation of arousal.

Sometimes our arousal spills over from one event to the next, influencing our response. Imagine arriving home after a fast run and finding a message that you got a longed-for job. With arousal lingering from the run, will you feel more excited than you would be if you hear this news after awakening from a nap?

To explore this spillover effect, Schachter and Singer injected college men with epinephrine, a hormone that triggers feelings of arousal. Picture yourself as a participant. After receiving the injection, you go to a waiting room. You find yourself with another person (actually an accomplice of the experimenters) who is acting either joyful or irritated. As you observe this person, you begin to feel your heart race, your body flush, and your breathing become more rapid. If you had been told to expect these effects from the injection, what would you feel? The actual volunteers felt little emotion—because they assumed their arousal was caused by the drug. But if you had been told the injection would produce no effects, what would you feel? Perhaps you would react as another group of participants did. They “caught” the apparent emotion of the other person in the waiting room. They became happy if the accomplice was acting joyful, and testy if the accomplice was acting irritated.

We can experience a stirred-up state as one emotion or another, depending on how we interpret and label it. Dozens of experiments have demonstrated this effect (Reisenzein, 1983; Sinclair et al., 1994; Zillmann, 1986). As one happiness researcher noted, “Feelings that one interprets as fear in the presence of a sheer drop may be interpreted as lust in the presence of a sheer blouse” (Gilbert, 2006).

The point to remember: Arousal fuels emotion; cognition channels it.

Zajonc, LeDoux, and Lazarus: Emotion and the Two-Track Brain

Is the heart always subject to the mind? Must we always interpret our arousal before we can experience an emotion? No, said Robert Zajonc [ZI-yence] (1980, 1984a). He argued that we actually have many emotional reactions apart from, or even before, our interpretation of a situation. Can you recall liking something or someone immediately, without knowing why? These reactions often reflect the automatic processing that takes place in our two-track mind.

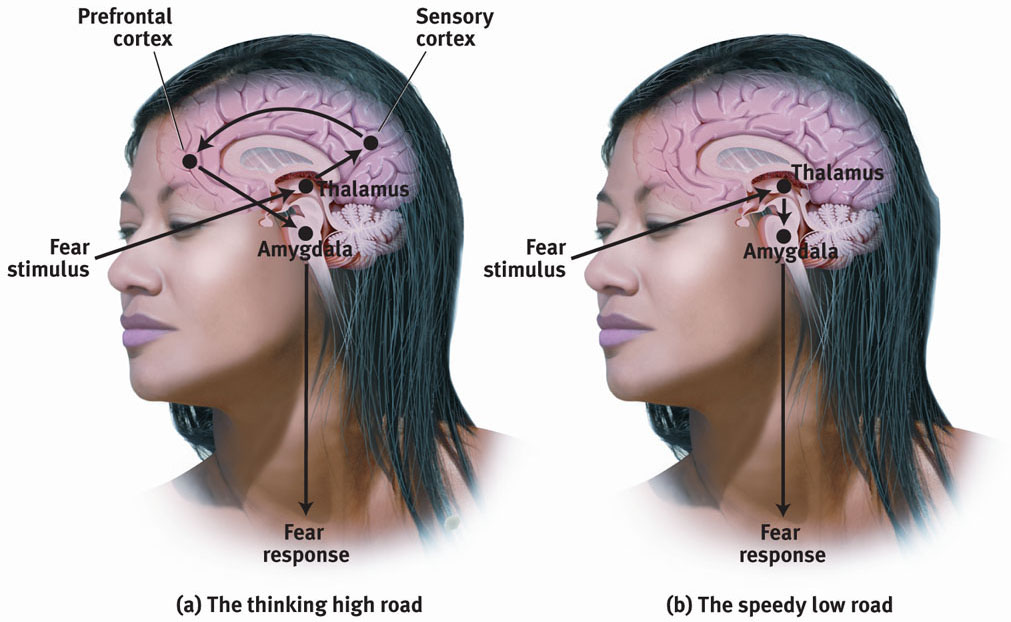

Our emotional responses are the final step in a process that can follow two different pathways in our brain, both via the thalamus. Some emotions, especially our more complex feelings, like hatred and love, travel a “high road” to the brain’s cortex (FIGURE 9.11a). There, we analyze and label information before we order a response via the amygdala (an emotion-control center).

271

But sometimes our emotions (especially simple likes, dislikes, and fears) take what Joseph LeDoux (2002) has called the “low road.” This neural shortcut bypasses the cortex (Figure 9.11b). Following the low road, a fear-provoking stimulus travels from the eye or the ear directly to the amygdala. This shortcut enables our greased-lightning emotional response (“Life in danger!”) before our brain interprets the exact source of danger. Like speedy reflexes that also operate apart from the brain’s thinking cortex, the amygdala’s reactions are so fast that we may not be aware of what’s happened (Dimberg et al., 2000).

The amygdala’s structure makes it easier for our feelings to hijack our thinking than for our thinking to rule our feelings (LeDoux & Armony, 1999). It sends more neural projections up to the cortex than it receives back. In the forest, we can jump when we hear rustling in nearby bushes and leave it to our cortex (via the high road) to decide later whether the sound was made by a snake or by the wind. Such experiences support Zajonc’s belief that some of our emotional reactions involve no deliberate thinking.

Emotion researcher Richard Lazarus (1991, 1998) agreed that our brain processes vast amounts of information without our conscious awareness, and that some emotional responses do not require conscious thinking. Much of our emotional life operates via the automatic, speedy low road. But, he asked, how would we know what we are reacting to if we did not in some way appraise the situation? The appraisal may be effortless and we may not be conscious of it, but it is still a mental function. To know whether a stimulus is good or bad, the brain must have some idea of what it is (Storbeck et al., 2006). Thus, said Lazarus, emotions arise when we appraise an event as harmless or dangerous, whether we truly know it is or not. We appraise the sound of the rustling bushes as the presence of a threat. Later, we learn that it was “just the wind.”

Let’s sum up (see also TABLE 9.1). As Zajonc and LeDoux have demonstrated, some emotional responses—especially simple likes, dislikes, and fears—involve no conscious thinking. We may fear a big spider, even if we “know” it is harmless. Such responses are difficult to alter by changing our thinking. We may automatically like one person more than another. This instant appeal can even influence our political decisions if we vote (as many people do) for the candidate we like over the candidate expressing positions closer to our own (Westen, 2007).

272

But other emotions—including moods such as depression, and complex feelings such as hatred and love—are, as Lazarus, Schachter, and Singer predicted, greatly affected by our interpretations, memories, and expectations. For these emotions, we have more conscious control. As you will see in Chapter 12, learning to think more positively about ourselves and the world around us can help us feel better.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 9.9

According to the Cannon-Bard theory, (a) our physiological response to a stimulus (for example, a pounding heart), and (b) the emotion we experience (for example, fear) occur _________ (simultaneously/sequentially). According to the James-Lange theory, (a) and (b) occur _________ (simultaneously/sequentially).

simultaneously; sequentially (first the physiological response, and then the experienced emotion)

Question 9.10

According to Schachter and Singer, two factors lead to our experience of an emotion: (1) physiological arousal and (2) _________ appraisal.

cognitive

Question 9.11

Emotion researchers have disagreed about whether emotional responses occur in the absence of cognitive processing. How would you characterize the approach of each of the following researchers: Zajonc, LeDoux, Lazarus, Schachter, and Singer?

Zajonc and LeDoux suggested that we experience some emotions without any conscious, cognitive appraisal. Lazarus, Schachter, and Singer emphasized the importance of appraisal and cognitive labeling in our experience of emotion.