Embodied Emotion

Whether you are falling in love or grieving a loved one’s death, you need little convincing that emotions involve the body. Feeling without a body is like breathing without lungs. Some physical responses are easy to notice; others happen without your awareness. Indeed, many take place at the level of your brain’s neurons.

Whether you are falling in love or grieving a loved one’s death, you need little convincing that emotions involve the body. Feeling without a body is like breathing without lungs. Some physical responses are easy to notice; others happen without your awareness. Indeed, many take place at the level of your brain’s neurons.

The Basic Emotions

9-8 What are some basic emotions?

Carroll Izard (1977) isolated 10 basic emotions: joy, interest-excitement, surprise, sadness, anger, disgust, contempt, fear, shame, and guilt. Most are present in infancy (FIGURE 9.12). Although others believe that pride and love are basic emotions (Shaver et al., 1996; Tracey & Robins, 2004), Izard has argued that they are combinations of the basic 10. Other researchers have asked a different question: Do our different emotions have distinct arousal footprints? Before answering that question, let’s review what happens in your autonomic nervous system when your body becomes aroused.

Emotions and the Autonomic Nervous System

9-9 What is the link between emotional arousal and the autonomic nervous system?

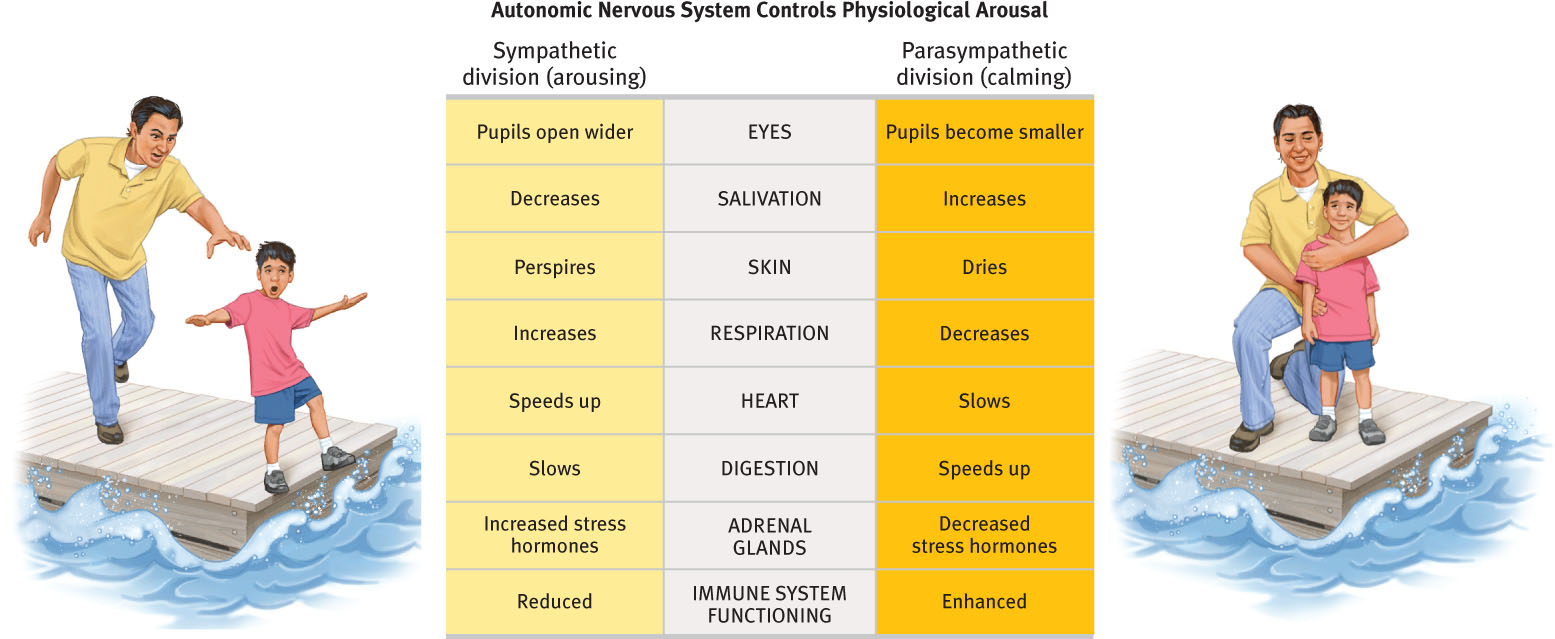

As we saw in Chapter 2, in a crisis, the sympathetic division of your autonomic nervous system (ANS) mobilizes your body for action (FIGURE 9.13). It triggers your adrenal glands to release stress hormones. To provide energy, your liver pours extra sugar into your bloodstream. To help burn the sugar, your breathing rate increases to supply needed oxygen. Your heart rate and blood pressure increase. Your digestion slows, allowing blood to move away from your internal organs and toward your muscles. With blood sugar driven into the large muscles, running becomes easier. Your pupils open wider, letting in more light. To cool your stirred-up body, you perspire. If you were wounded, your blood would clot more quickly.

273

After your next crisis, think of this: Without any conscious effort, your body’s response to danger is wonderfully coordinated and adaptive—preparing you for fight or flight. When the crisis passes, the parasympathetic division of your ANS gradually calms your body, as stress hormones slowly leave your bloodstream.

The Physiology of Emotions

9-10 How do our body states relate to specific emotions? How effective are polygraphs in using body states to detect lies?

“No one ever told me that grief felt so much like fear. I am not afraid, but the sensation is like being afraid. The same fluttering in the stomach, the same restlessness, the yawning. I keep on swallowing.”

C. S. Lewis, A Grief Observed, 1961

Imagine another scene. You are conducting an experiment, measuring the body’s responses to different emotions. In each of four rooms, you have someone watching a movie. In the first, the person is viewing a horror show. In the second, the viewer watches an anger-provoking film. In the third, someone is watching a sexually arousing film. In the fourth, the person is viewing an utterly boring movie. From the control center, you are tracking each person’s physical responses, measuring perspiration, breathing, and heart rate. Do you think you could tell who is frightened? Who is angry? Who is sexually aroused? Who is bored?

With training, you could probably pick out the bored viewer. But spotting the bodily differences among fear, anger, and sexual arousal would be much more difficult (Barrett, 2006). Different emotions do not have sharply different biological signatures.

Despite similar bodily responses, sexual arousal, fear, and anger feel different to you and me, and they often look different to others. We may appear “paralyzed with fear” or “ready to explode.”

With the help of sophisticated laboratory tools, researchers have pinpointed some subtle indicators of different emotions (Lench et al., 2011). The finger temperatures and hormone secretions that accompany fear and rage do sometimes differ (Ax, 1953; Levenson, 1992). Fear and joy stimulate different facial muscles. During fear, your brow muscles tense. During joy, muscles in your cheeks and under your eyes pull into a smile (Witvliet & Vrana, 1995).

Brain scans and EEGs reveal that some emotions also differ in their brain circuits (Panksepp, 2007). When you experience negative emotions such as disgust, your right frontal cortex is more active than your left frontal cortex. People who are prone to depression, or who have generally negative personalities, also show more activity in their right frontal lobe (Harmon-Jones et al., 2002). One not-unhappy wife reported that her husband, who had lost part of his right frontal lobe in brain surgery, became less irritable and more affectionate (Goleman, 1995). My father, after a right-hemisphere stroke at age 92, lived the last two years of his life with happy gratitude and nary a complaint or negative emotion.

274

When you experience positive moods—when you are enthusiastic, energized, and happy—your left frontal lobe will be more active. Increased left frontal lobe activity is found in people with positive personalities—jolly infants and alert, energetic, and persistently goal-directed adults (Davidson, 2012; Urry et al., 2004). When you’re happy and you know it, your brain will surely show it.

To sum up, we can’t easily see differences in emotions from tracking heart rate, breathing, and perspiration. But facial expressions and brain activity can vary from one emotion to another. So do we, like Pinocchio, give off telltale signs when we lie? For more on that question, see Thinking Critically About: Lie Detection.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 9.12

How do the two divisions of the autonomic nervous system affect our emotional responses?

The sympathetic division of the ANS arouses us for more intense experiences of emotion, pumping out stress hormones to prepare our body for fight or flight. The parasympathetic division of the ANS takes over when a crisis passes, restoring our body to a calm physiological and emotional state.

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT

Lie Detection

Can a lie detector—a polygraph—reveal lies? Polygraphs don’t really detect lies. Instead, they measure emotion-linked changes in breathing, heart rate, and perspiration. Imagine yourself attached to one of these machines, trying to relax. An examiner asks you questions and monitors your responses. She asks, “In the last 20 years, have you ever taken something that didn’t belong to you?” This item is a control question, aimed at making everyone a little nervous. If you lie and say “No!” (as many people do), your nervousness will register as arousal, which the polygraph will detect. This response will give the examiner a baseline, a useful comparison for your responses to critical questions. (“Did you ever steal anything from your previous employer?”) If your responses to critical questions are weaker than to control questions, the examiner will infer you are telling the truth. The idea is that only a thief becomes nervous when denying a theft.

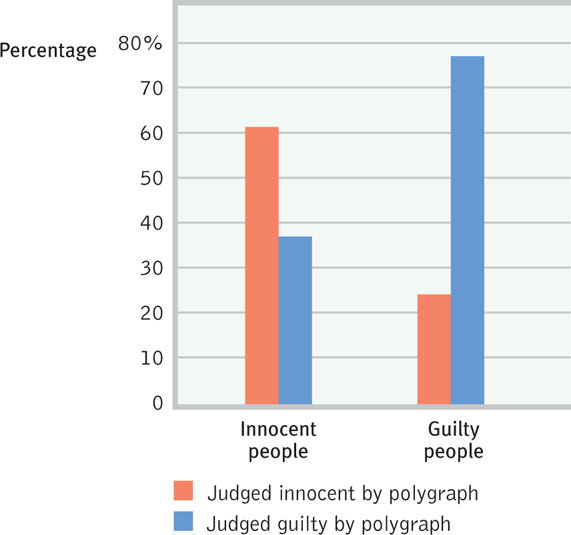

Critics point out two problems. First, our bodily arousal is much the same from one emotion to another. Our bodies react to anxiety, irritation, and guilt in very similar ways. Second, many innocent people do get tense and nervous when accused of a crime or bad act. Many rape victims, for example, have “failed” these tests because they had strong emotional reactions while telling the truth about the rapist (Lykken, 1991). About one-third of the time, polygraph test results are just wrong (FIGURE 9.14).

A 2002 U.S. National Academy of Sciences report noted that “no spy has ever been caught [by] using the polygraph.” It is not for lack of trying. The CIA is one of several U.S. agencies that together have spent millions of dollars testing tens of thousands of employees. Did the test catch Aldrich Ames, a Russian spy within the CIA who enjoyed a very lavish lifestyle? Ames took many “polygraph tests and passed them all,” noted physicist Robert Park (1999). “Nobody thought to investigate the source of his sudden wealth—after all, he was passing the lie detector tests.”

A more effective approach to lie detection uses a guilty knowledge test, with questions focused on specific crime-scene details known only to the police and the guilty person (Ben-Shakhar & Elaad, 2003). If a camera and computer had been stolen, for example, only a guilty person should react strongly to the brand names of the stolen items. Given enough such specific probes, an innocent person will seldom be wrongly accused.

275