Expressed and Experienced Emotion

There is a simple method of detecting people’s emotions: Read their body language, listen to their voice tones, and study their faces. People’s expressive behavior reveals their emotion. Does this nonverbal language vary with culture, or is it the same everywhere? And do our expressions influence what we feel?

There is a simple method of detecting people’s emotions: Read their body language, listen to their voice tones, and study their faces. People’s expressive behavior reveals their emotion. Does this nonverbal language vary with culture, or is it the same everywhere? And do our expressions influence what we feel?

Detecting Emotion in Others

9-11 How do we communicate nonverbally? How do women and men differ in these abilities?

All of us communicate without words. Westerners “read” a firm handshake as evidence of an outgoing, expressive personality (Chaplin et al., 2000). A glance or a stare can communicate intimacy, submission, or dominance (Kleinke, 1986). When two people are passionately in love, they typically spend time—quite a bit of time—gazing into each other’s eyes (Rubin, 1970). Would such gazes stir these feelings between strangers? To find out, researchers asked male-female pairs of strangers to gaze intently for 2 minutes either at each other’s hands or into each other’s eyes. After separating, the eye gazers reported feeling a tingle of attraction and affection (Kellerman et al., 1989).

Most of us read nonverbal cues fairly well. Shown 10 seconds of video from the end of a speed-dating interaction, people can often detect whether one person is attracted to the other (Place et al., 2009). We are especially good at detecting nonverbal threats. A single angry face will “pop out” of a crowd faster than a single happy one (Fox et al., 2000; Hansen & Hansen, 1988; Öhman et al., 2001). Even when hearing another language, most people can easily detect anger (Scherer et al., 2001).

Despite our brain’s emotion-detecting skill, we find it difficult to detect deceiving expressions (Porter & ten Brinke, 2008). When researchers summarized 206 studies of sorting truth from lies, people were just 54 percent accurate—barely better than a coin toss (Bond & DePaulo, 2006). Are experts more skilled at spotting lies? No. With the possible exception of police professionals in high-stakes situations, even they don’t beat chance by much (Bond & DePaulo, 2008; O’Sullivan et al., 2009). The behavioral differences between liars and truth tellers are too slight for most of us to detect (Hartwig & Bond, 2011).

Some of us are, however, more skilled than others at reading emotions. In one study, hundreds of people were asked to name the emotion displayed in brief film clips. The clips showed portions of a person’s emotionally expressive face or body, sometimes accompanied by a garbled voice (Rosenthal et al., 1979). For example, one 2-second scene revealed only the face of an upset woman. After watching the scene, viewers would state whether the woman was criticizing someone for being late or was talking about her divorce. Given such “thin slices,” women have generally been the better emotion detectors (Hall, 1984, 1987). Women have also surpassed men in other assessments of emotional cues, such as deciding whether a male-female couple is a genuine romantic couple or a posed phony couple (Barnes & Sternberg, 1989).

Women’s skill at decoding emotions may help explain why women tend to respond with greater emotion (Vigil, 2009). In studies of 23,000 people from 26 cultures, women more than men have reported themselves open to feelings (Costa et al., 2001). That helps explain the extremely strong perception (nearly all 18- to 29-year-old Americans in one survey) that emotionality is “more true of women” (Newport, 2001).

One exception: Quickly—imagine an angry face. What gender is the person? If you’re like 3 in 4 Arizona State University students in the original study, you imagined a male (Becker et al., 2007). The researchers also found that when a gender-neutral face was made to look angry, most people perceived it as male. If the face was smiling, they were more likely to perceive it as female (FIGURE 9.15). Anger strikes most people as a more masculine emotion.

276

Are there gender differences in empathy? If you have empathy, you identify with others and imagine what it must be like to walk in their shoes. You rejoice with those who rejoice and weep with those who weep. In surveys, women are far more likely than men to describe themselves as empathic. Actually, measures of body responses, such as one’s heart rate while seeing another’s distress, reveal a much smaller gender gap (Eisenberg & Lennon, 1983; Rueckert et al., 2010).

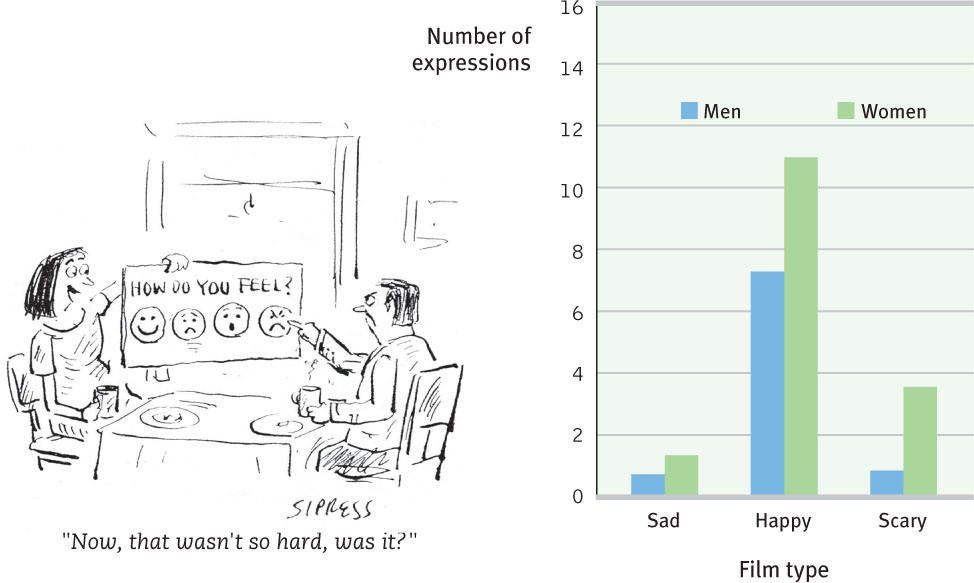

Nevertheless, females are somewhat more likely to express empathy—to cry and to report distress when observing someone in distress. As FIGURE 9.16 shows, this gender difference was clear in videotapes of men and women watching film clips that were sad (children with a dying parent), happy (slapstick comedy), or frightening (a man nearly falling off the ledge of a tall building) (Kring & Gordon, 1998; Vigil, 2009). Women also more deeply experience emotional events, such as viewing mutilation pictures. (Brain scans show more activity in areas sensitive to emotion.) Women also tend to remember the scenes better three weeks later (Canli et al., 2002).

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 9.13

______ (Women/Men) report experiencing emotions more deeply, and they tend to be more adept at reading nonverbal behavior.

Women

Culture and Emotional Expression

9-12 How are nonverbal expressions of emotion understood within and across cultures?

The meaning of gestures varies from culture to culture. U.S. President Richard Nixon learned this while traveling in Brazil. He made the North American “A-OK” sign before a welcoming crowd, not knowing it was a crude insult in that country. In 1968, North Korea publicized photos of supposedly happy officers from a captured U.S. Navy spy ship. In the photo, three men had raised their middle fingers, telling their captors—who didn’t recognize the cultural gesture—it was a “Hawaiian good luck sign” (Fleming & Scott, 1991).

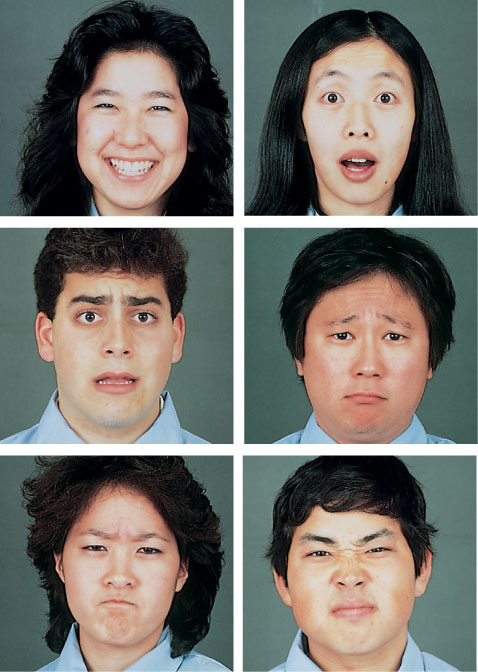

Do facial expressions also have different meanings in different cultures? To find out, researchers showed photographs of some facial expressions to people in different parts of the world and asked them to guess the emotion (Ekman et al., 1975, 1987, 1994; Izard, 1977, 1994). You can try this matching task yourself by pairing the six emotions with the six faces of FIGURE 9.17.

Answers, from left to right, top to bottom: happiness, surprise, fear, sadness, anger, disgust.

Regardless of your cultural background, you probably did pretty well. A smile’s a smile the world around. Ditto for anger, and to a lesser extent the other basic expressions (Elfenbein & Ambady, 1999). (There is no culture where people frown when they are happy.) We do slightly better when judging emotional displays from our own culture (Elfenbein & Ambady, 2002, 2003a,b). Nevertheless, the outward signs of emotion are generally the same across cultures.

277

Tom Purslow/Manchester United via Getty Images

Musical expressions of emotions also cross cultures. Happy and sad music feels happy and sad around the world. Whether you live in an African village or a European city, fast-paced music seems happy, and slow-paced music seems sadder (Fritz et al., 2009).

Do these shared emotional categories reflect shared cultural experiences, such as movies and TV programs that are seen around the world? Apparently not. Paul Ekman and his team asked isolated people in New Guinea to respond to such statements as, “Pretend your child has died.” When North American collegians viewed the taped responses, they easily read the New Guineans’ facial reactions.

So we can say that facial muscles speak a fairly universal language. This discovery would not have surprised Charles Darwin (1809–1882). In The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), Darwin argued that in prehistoric times, before our ancestors communicated in words, they communicated threats, greetings, and submission with facial expressions. Such expressions helped them survive and became part of our shared heritage (Hess & Thibault, 2009). A sneer, for example, retains elements of an animal’s baring its teeth in a snarl. Emotional expressions may enhance our survival in other ways, too. Surprise raises our eyebrows and widens our eyes, helping us take in more information. Disgust wrinkles our nose, closing out foul odors.

“For news of the heart, ask the face.”

Guinean proverb

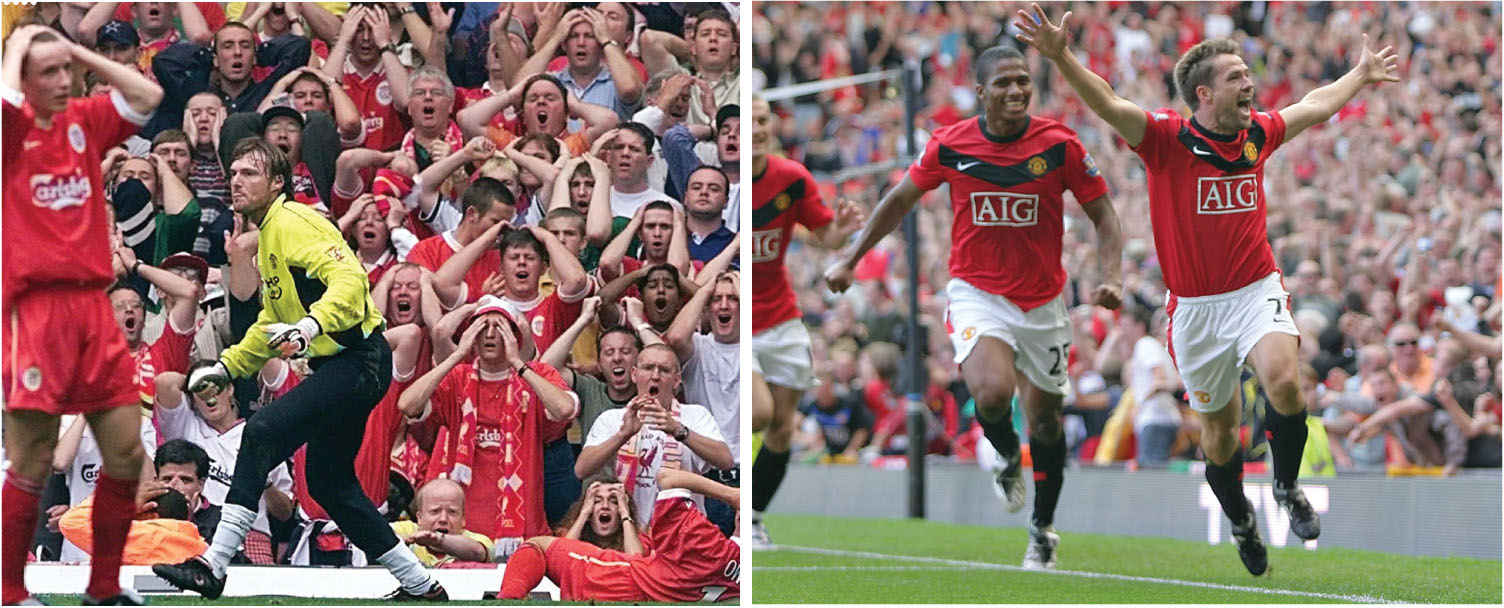

Smiles are social as well as emotional events. Bowlers seldom smile when they score a strike. They smile when they turn to face their companions (Jones et al., 1991; Kraut & Johnston, 1979). Olympic gold medalists typically don’t smile when they are awaiting their ceremony. But they wear broad grins when interacting with officials and facing the crowd and cameras (Fernández-Dols & Ruiz-Belda, 1995). Even natively blind athletes, who have never observed smiles, display the same social smiles in such situations (Matsumoto & Willingham, 2006, 2009).

Although we humans share a universal facial language, it has been adaptive for us to interpret faces in particular contexts (FIGURE 9.18). People judge an angry face set in a frightening situation as afraid, and a fearful face set in a painful situation as pained (Carroll & Russell, 1996). Movie directors harness this tendency by creating contexts and soundtracks that amplify our perceptions of particular emotions.

Whether we perceive the man’s face on the far right as disgusted or angry depends on which body his face appears on (Aviezer et al., 2008).

“Angry, Disgusted, or Afraid? Studies on the Malleability of Emotion Perception,” Hillel Aviezer, Ran R. Hassin, Jennifer Ryan, Cheryl Grady, Josh Susskind, Adam Anderson, Morris Moscovitch, Shlomo Bentin

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 9.14

Are people in different cultures more likely to differ in their interpretations of facial expressions, or of gestures?

gestures

The Effects of Facial Expressions

9-13 How do facial expressions influence our feelings?

As famed psychologist William James (1890) struggled with feelings of depression and grief, he came to believe that we can control our emotions by going “through the outward movements” of any emotion we want to experience. “To feel cheerful,” he advised, “sit up cheerfully, look around cheerfully, and act as if cheerfulness were already there.”

278

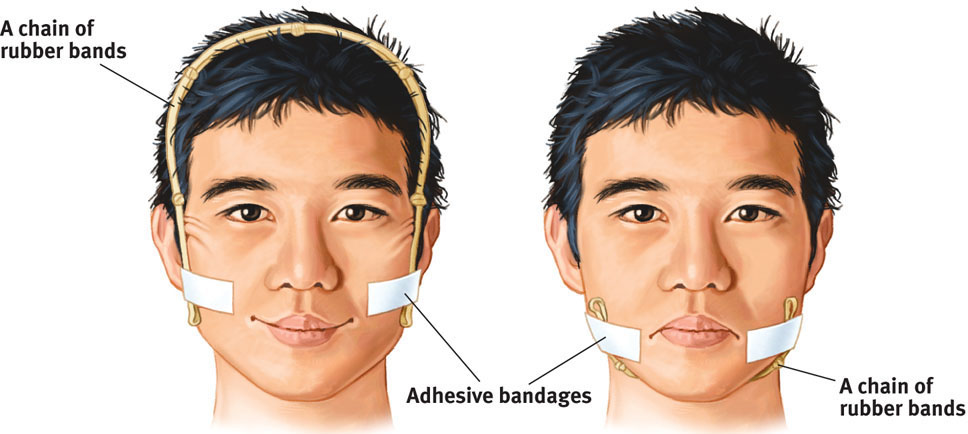

Was James right? Can our outward expressions and movements trigger our inner feelings and emotions? You can test his idea: Fake a big grin. Now scowl. Can you feel the “smile therapy” difference? Participants in dozens of experiments have felt a difference. For example, researchers tricked students into making a frowning expression by asking them to “contract these muscles” and “pull your brows together” (Laird et al., 1974, 1984, 1989). (The students thought they were helping the researchers attach facial electrodes.) The result? The students reported feeling a little angry. So, too, for other basic emotions. For example, people reported feeling more fear than anger, disgust, or sadness when made to construct a fearful expression (Duclos et al., 1989). (They were told, “Raise your eyebrows. And open your eyes wide. Move your whole head back, so that your chin is tucked in a little bit, and let your mouth relax and hang open a little.”) This facial feedback effect has been repeated many times, in many places, for many basic emotions (FIGURE 9.19). Just activating one of the smiling muscles by holding a pen in the teeth (rather than with the lips, which activates a frowning muscle) is enough to make cartoons seem more amusing (Strack et al., 1988).

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 9.15

(1) Based on the facial feedback effect, how might students in this experiment report feeling when the rubber bands raise their cheeks as though in a smile? (2) How might they report feeling when the rubber bands pull their cheeks downward?

(1) Most report feeling more happy than sad when their cheeks are raised upward. (2) Most report feeling more sad than happy when their cheeks are pulled downward.

So, your face is more than a billboard that displays your feelings; it also feeds your feelings. No wonder depressed patients reportedly feel better after between-the-eyebrows Botox injections that freeze their frown muscles (Wollmer et al., 2012). Botox paralysis of the frowning muscles also slows people’s reading of sadness- or anger-related sentences, and it slows activity in emotion-related brain circuits (Havas et al., 2010; Hennenlotter et al., 2008). In such ways, Botox smooths life’s emotional wrinkles.

Other studies have noted a similar behavior feedback effect (Flack, 2006; Snodgrass et al., 1986). Try it. Walk for a few minutes with short, shuffling steps, keeping your eyes downcast. Now walk around taking long strides, with your arms swinging and your eyes looking straight ahead. Can you feel your mood shift? Going through the motions awakens the emotions.

You can use your understanding of feedback effects to become more empathic—to feel what others feel. See what happens if you let your own face mimic another person’s expression. Acting as another acts helps us feel what another feels (Vaughn & Lanzetta, 1981). Indeed, natural mimicry of others’ emotions helps explain why emotions are contagious (Dimberg et al., 2000; Neumann & Strack, 2000).

279

We have seen how our motivated behaviors, triggered by the forces of nature and nurture, often go hand in hand with emotional responses. Our psychological emotions likewise come equipped with physical reactions. Nervous about an upcoming date, we feel stomach butterflies. Anxious over public speaking, we head for the bathroom. Smoldering over a family conflict, we get a splitting headache. Negative emotions and the prolonged high arousal that may accompany them can tax the body and harm our health. You’ll hear more about this in Chapter 10. In that chapter, we’ll also take a closer look at the emotion of happiness.