Preface

PSYCHOLOGY IS FASCINATING, and so relevant to our everyday lives. Psychology’s insights enable us to be better students, more tuned-in friends and partners, more effective co-workers, and wiser parents. With this new edition, we hope to captivate students with what psychologists are learning about our human nature, to help them think more like psychological scientists, and, as the title implies, to help them relate psychology to their own lives—their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

For those of you familiar with other Myers introductory psychology texts, you may be surprised at how very different this text is. We have created this uniquely student-friendly book with the help of input from thousands of instructors and students (by way of surveys, focus groups, content and design reviews, and class testing).

New Co-Author

For this new edition I [DM] welcome my new co-author, University of Kentucky professor Nathan DeWall. (For more information and videos that introduce Nathan DeWall and our collaboration, see www.worthpublishers.com/myersdewall.) Nathan is not only one of psychology’s “rising stars” (as the Association for Psychological Science rightly said in 2011), he also is an award-winning teacher and someone who shares my passion for writing—and for communicating psychological science through writing. Although I continue as lead author, Nathan’s fresh insights and contributions are already enriching this book, especially for this third edition, through his leading the revision of Chapters 4, 10, 11, and 14. But my fingerprints are also on those chapter revisions, even as his are on the other chapters. With support from our wonderful editors, this is a team project. In addition to our work together on the textbook, Nathan and I enjoy co-authoring the Teaching Current Directions in Psychological Science column in the APS Observer.

What Else Is New in the Third Edition?

In addition to the long, chapter-by-chapter list of Content Changes that follows this preface, other significant changes have been made to the overall format and presentation of this new third edition.

New Study System Follows Best Practices From Learning and Memory Research

The new learning system harnesses the testing effect, which documents the benefits of actively retrieving information through self-testing (FIGURE 1). Thus, each chapter now offers 12 to 15 new Retrieve + Remember questions interspersed throughout (FIGURE 2). Creating these desirable difficulties for students along the way optimizes the testing effect, as does immediate feedback (via inverted answers beneath each question).

In addition, each main section of text begins with numbered questions that establish learning objectives and direct student reading. The Chapter Review section repeats these questions as a further self-testing opportunity (with answers in the Complete Chapter Reviews appendix). The Chapter Review section also offers a page-referenced list of Terms and Concepts to Remember, and new Chapter Test questions in multiple formats to promote optimal retention.

Each chapter closes with In Your Everyday Life questions, designed to help students make the concepts more personally meaningful, and therefore more memorable. These questions are also designed to function as excellent group discussion topics. The text offers hundreds of interesting applications to help students see just how applicable psychology’s concepts are to everyday life.

These new features enhance the Survey-Question-Read-Retrieve-Review (SQ3R) format. Chapter outlines allow students to survey what’s to come. Main sections begin with a learning objective question (now more carefully directed and appearing more frequently) that encourages students to read actively. Periodic Retrieve + Remember sections and the Chapter Review (with repeated Learning Objective Questions, Key Terms list, and complete Chapter Test) encourage students to test themselves by retrieving what they know and reviewing what they don’t. (See Figure 2 for a Retrieve + Remember sample.)

Reorganized Chapters and More Than 600 New Research Citations

Scattered throughout this book, students will find interesting and informative review notes and quotes from researchers and others that will encourage them to be active learners and to apply their new knowledge to everyday life.

Thousands of instructors and students have helped guide our creation of Psychology in Everyday Life, as have our reading and correspondence. The result is a unique text, now thoroughly revised in this third edition, which includes more than 600 new citations. Some of the most exciting recent research has happened in the area of biological psychology, including cognitive neuroscience, dual processing, and epigenetics. See p. xxxiii for a chapter-by-chapter list of significant Content Changes. In addition to the new study aids and updated coverage, we’ve introduced the following organizational changes:

- Chapter 1 concludes with a new section, “Improve Your Retention—and Your Grades.” This guide will help students replace ineffective and inefficient old habits with new habits that increase retention and success.

- Chapter 3, Developing Through the Life Span, has been shortened by moving the Aging and Intelligence coverage to Chapter 8, Thinking, Language, and Intelligence.

- Chapter 7, Memory, follows a new format, and more clearly explains how different brain networks process and retain memories. We worked closely with Janie Wilson, Professor of Psychology at Georgia Southern University and Vice President for Programming of the Society for the Teaching of Psychology, on this chapter’s revision.

- Chapter 10, Stress, Health, and Human Flourishing, now includes a discussion of happiness and subjective well-being, moved here from the Motivation and Emotion chapter.

- Chapter 11, Personality, offers more complete coverage of clinical perspectives, including improved coverage of modern-day psychodynamic approaches, which are now more clearly distinguished from their historical Freudian roots.

- The Social Psychology chapter now follows the Personality chapter.

- Chapter 13, Psychological Disorders, now includes coverage of eating disorders, previously in the Motivation and Emotion chapter. This chapter has also been reorganized to reflect changes to psychiatry’s latest edition of its diagnostic manual—the DSM-5.

- There are two new text appendices: Statistical Reasoning in Everyday Life, and Subfields of Psychology.

More Design Innovations

With help from student and instructor design reviewers, the new third edition retains the best of the easy-to-read three-column design but with a cleaner new look that makes navigation easier thanks to fewer color-distinguished features, a softer color palette, and closer connection between narrative coverage and its associated visuals.

Our three-column format is rich with visual support. It responds to students’ expectations, based on what they have told us about their reading, both online and in print. The narrow column width eliminates the strain of reading across a wide page. Illustrations appear near or within the pertinent text column, which helps students see them in the appropriate context. Key terms are defined near where they are introduced.

key terms Look for complete definitions of each important term in a page corner near the term’s introduction in the narrative.

In written reviews, students compared our three-column design with a traditional one-column design (without knowing which was ours). They unanimously preferred the three-column design. It was, they said, “less intimidating” and “less overwhelming” and it “motivated” them to read on.

In this edition, we’ve also adjusted the font used for research citations. In psychology’s journals and textbooks, parenthetical citations appropriately assign credit and direct readers to sources. But they can also form a visual hurdle. An instructor using the second edition of Psychology in Everyday Life suggested a new, less intrusive style, which has been encouraged by most of our reviewers. We’ve honored APA reference style with parenthetical citations (rather than, say, end notes), yet we’ve eased readability by reducing the strength of the citation font. The first instance of a citation is called out in Chapter 1 and explained to students who may be unfamiliar with the APA style for sourcing.

Dedicated Versions of Next-Generation Media

This third edition is accompanied by the new LaunchPad, with carefully crafted, prebuilt assignments, LearningCurve formative assessment activities, and Assess Your Strengths projects. This system also incorporates the full range of Worth’s psychology media products. (For details, see p. xxiv.)

What Continues in the Third Edition?

Eight Guiding Principles

Despite all the exciting changes, this new edition retains its predecessors’ voice, as well as much of the content and organization. It also retains the goals—the guiding principles—that have animated all of the Myers texts:

Facilitating the Learning Experience

- To teach critical thinking By presenting research as intellectual detective work, we illustrate an inquiring, analytical mind-set. Whether students are studying development, cognition, or social behavior, they will become involved in, and see the rewards of, critical reasoning. Moreover, they will discover how an empirical approach can help them evaluate competing ideas and claims for highly publicized phenomena—ranging from ESP and alternative therapies to hypnosis and repressed and recovered memories.

- To integrate principles and applications Throughout—by means of anecdotes, case histories, and the posing of hypothetical situations—we relate the findings of basic research to their applications and implications. Where psychology can illuminate pressing human issues—be they racism and sexism, health and happiness, or violence and war—we have not hesitated to shine its light.

- To reinforce learning at every step Everyday examples and rhetorical questions encourage students to process the material actively. Concepts presented earlier are frequently applied, and reinforced, in later chapters. For instance, in Chapter 1, students learn that much of our information processing occurs outside of our conscious awareness. Ensuing chapters drive home this concept. Numbered Learning Objective Questions at the beginning of each main section, Retrieve + Remember self-tests throughout each chapter, a marginal glossary, and Chapter Review key terms lists and self-tests help students learn and retain important concepts and terminology.

Demonstrating the Science of Psychology

- To exemplify the process of inquiry We strive to show students not just the outcome of research, but how the research process works. Throughout, the book tries to excite the reader’s curiosity. It invites readers to imagine themselves as participants in classic experiments. Several chapters introduce research stories as mysteries that progressively unravel as one clue after another falls into place.

- To be as up-to-date as possible Few things dampen students’ interest as quickly as the sense that they are reading stale news. While retaining psychology’s classic studies and concepts, we also present the discipline’s most important recent developments. In this edition, 250 references are dated 2011–2013. Likewise, the new photos and everyday examples are drawn from today’s world.

- To put facts in the service of concepts Our intention is not to fill students’ intellectual file drawers with facts, but to reveal psychology’s major concepts—to teach students how to think, and to offer psychological ideas worth thinking about. In each chapter, we place emphasis on those concepts we hope students will carry with them long after they complete the course. Always, we try to follow Albert Einstein’s purported dictum that “everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.” Learning Objective Questions and Retrieve + Remember questions throughout each chapter help students focus on the most important concepts.

Promoting Big Ideas and Broadened Horizons

- To enhance comprehension by providing continuity Many chapters have a significant issue or theme that links subtopics, forming a thread that ties the chapter together. The Learning chapter conveys the idea that bold thinkers can serve as intellectual pioneers. The Thinking, Language, and Intelligence chapter raises the issue of human rationality and irrationality. The Psychological Disorders chapter conveys empathy for, and understanding of, troubled lives. Other threads, such as cognitive neuroscience, dual processing, and cultural and gender diversity, weave throughout the whole book, and students hear a consistent voice.

- To convey respect for human unity and diversity Throughout the book, readers will see evidence of our human kinship—our shared biological heritage, our common mechanisms of seeing and learning, hungering and feeling, loving and hating. They will also better understand the dimensions of our diversity—our individual diversity in development and aptitudes, temperament and personality, and disorder and health; and our cultural diversity in attitudes and expressive styles, child raising and care for the elderly, and life priorities.

The Writing

As with the second edition, we’ve written this book to be optimally accessible. The vocabulary is sensitive to students’ widely varying reading levels and backgrounds. And this book is briefer than many texts on the market, making it easier to fit into one-term courses. Psychology in Everyday Life offers a complete survey of the field, but it is a more manageable survey. We strove to select the most humanly significant concepts. We continually asked ourselves while working, “Would an educated person need to know this? Would this help students live better lives?”

Culture and Gender—No Assumptions

Even more than in other Myers texts, we have written Psychology in Everyday Life with the diversity of student readers in mind.

- Gender: Extensive coverage of gender roles and gender identity and the increasing diversity of choices men and women can make.

- Culture: No assumptions about readers’ cultural backgrounds or experiences.

- Economics: No references to back yards, summer camp, vacations.

- Education: No assumptions about past or current learning environments; writing is accessible to all.

- Physical Abilities: No assumptions about full vision, hearing, movement.

- Life Experiences: Examples are included from urban, suburban, and rural/outdoor settings.

- Family Status: Examples and ideas are made relevant for all students, whether they have children or are still living at home, are married or cohabiting or single; no assumptions about sexual orientation.

Four Big Ideas

In the general psychology course, it can be a struggle to weave psychology’s disparate parts into a cohesive whole for students, and for students to make sense of all the pieces. In Psychology in Everyday Life, we have introduced four of psychology’s big ideas as one possible way to make connections among all the concepts. These ideas are presented in Chapter 1 and gently integrated throughout the text.

1. Critical Thinking Is Smart Thinking

We love to write in a way that gets students thinking and keeps them active as they read. Students will see how the science of psychology can help them evaluate competing ideas and highly publicized claims—ranging from intuition, subliminal persuasion, and ESP to left-brained/right-brained, alternative therapies, and repressed and recovered memories.

In Psychology in Everyday Life, students have many opportunities to learn or practice their critical thinking skills:

- Chapter 1 takes a unique, critical thinking approach to introducing students to psychology’s research methods. Understanding the weak points of our everyday intuition and common sense helps students see the need for psychological science. Critical thinking is introduced as a key term in this chapter (page 6).

- “Thinking Critically About …” boxes are found throughout the book. This feature models for students a critical approach to some key issues in psychology. For example, see “Thinking Critically About: The Stigma of Introversion” (Chapter 11) or “Thinking Critically About: Do Video Games Teach, or Release, Violence?” (Chapter 12). “Close-Up” boxes encourage application of the new concepts. For example, see “Close-Up: Waist Management” in Chapter 9, or “Close-Up: Pets Are Friends, Too” in Chapter 10.

- Detective-style stories throughout the text get students thinking critically about psychology’s key research questions. In Chapter 8, for example, we present as a puzzle the history of discoveries about where and how language happens in the brain. We guide students through the puzzle, showing them how researchers put all the pieces together.

- “Try this” and “think about it” style discussions and side notes keep students active in their study of each chapter. We often encourage students to imagine themselves as participants in experiments. In Chapter 12, for example, students take the perspective of participants in a Solomon Asch conformity experiment and, later, in one of Stanley Milgram’s obedience experiments. We’ve also asked students to join the fun by taking part in activities they can try along the way. Here are a few examples: In Chapter 5, they try out a quick sensory adaptation activity. In Chapter 9, they try matching expressions to faces and test the effects of different facial expressions on themselves. Throughout Chapter 11, students are asked to apply what they’re learning to the construction of a questionnaire for an Internet dating service.

- Critical examinations of pop psychology spark interest and provide important lessons in thinking critically about everyday topics. For example, Chapter 5 includes a close examination of ESP, and Chapter 7 addresses the controversial topic of repression of painful memories.

See TABLE 1 for a complete list of this text’s coverage of critical thinking topics.

| Critical thinking coverage may be found on the following pages: |

| A scientific model for studying psychology, p. 172 |

| Are intelligence tests biased?, pp. 249–250 |

| Are personality tests able to predict behavior?, p. 325 |

| Are there parts of the brain we don’t use?, p. 46 |

| Attachment style, development of, pp. 81–84 |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), p. 371 |

| Causation and the violence-viewing effect, p. 188 |

| Classifying psychological disorders, pp. 374–375 |

| Confirmation bias, p. 221 |

| Continuity vs. stage theories of development, pp. 93–94 |

| Correlation and causation, pp. 16–17, 84, 90 |

| Critical thinking defined, p. 7 |

| Critiquing the evolutionary perspective on sexuality, pp. 127–128 |

| Discovery of hypothalamus reward centers, pp. 41–42 |

| Do animals think and have language?, pp. 228–229 |

| Do lie detectors lie?, p. 274 |

| Do other species think and have language?, pp. 234–235 |

| Do video games teach, or release, violence?, pp. 358–359 |

| Does meditation enhance immunity?, pp. 298–299 |

| Effectiveness of “alternative” therapies, p. 422 |

| Emotion and the brain, pp. 40–42 |

| Emotional intelligence, p. 238 |

| Evolutionary science and human origins, p. 129 |

| Extrasensory perception, pp. 161–162 |

| Fear of flying vs. probabilities, pp. 224–225 |

| Freud’s contributions, p. 318 |

| Genetic and environmental influences on schizophrenia, pp. 398–400 |

| Group differences in intelligence, pp. 246–249 |

| Hindsight bias, pp. 9–10 |

| Hindsight explanations, pp. 127–128 |

| How do nature and nurture shape prenatal development?, pp. 69–71 |

| How do twin and adoption studies help us understand the effects of nature and nurture?, p. 72 |

| How does the brain process language?, pp. 232–233 |

| How much is gender socially constructed vs. biologically influenced?, pp. 110–115 |

| How valid is the Rorschach inkblot test?, pp. 316–317 |

| Human curiosity, pp. 1–2 |

| Humanistic perspective, evaluating, p. 321 |

| Hypnosis: dissociation or social influence?, pp. 156–157 |

| Importance of checking fears against facts, pp. 224–225 |

| Interaction of nature and nurture in overall development, pp. 85–86, 91 |

| Is dissociative identity disorder a real disorder?, pp. 402–403 |

| Is psychotherapy effective?, pp. 420–421 |

| Is repression a myth?, p. 318 |

| Limits of case studies, naturalistic observation, and surveys, pp. 14–15 |

| Limits of intuition, p. 9 |

| Nature, nurture, and perceptual ability, p. 150 |

| Overconfidence, pp. 10, 223 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), pp. 378–379 |

| Powers and perils of intuition, pp. 225–226 |

| Problem-solving strategies, pp. 220–221 |

| Psychic phenomena, p. 12 |

| Psychology: a discipline for critical thought, pp. 3–4, 9–12 |

| Religious involvement and longevity, pp. 299–301 |

| Scientific method, pp. 12–13 |

| Sexual desire and ovulation, p. 115 |

| Similarities and differences in social power between men and women, p. 109 |

| Stress and cancer, pp. 288–289 |

| Suggestive powers of subliminal messages, p. 136 |

| The divided brain, pp. 47–49 |

| The powers and limits of parental involvement on development, p. 91 |

| Using psychology to debunk popular beliefs, p. 6 |

| Values and psychology, pp. 22–23 |

| What does selective attention teach us about consciousness?, pp. 51–52 |

| What factors influence sexual orientation?, pp. 121–125 |

| What is the connection between the brain and the mind?, p. 37 |

| Wording effects, pp. 15 |

2. Behavior Is a Biopsychosocial Event

Students will learn that we can best understand human behavior if we view it from three levels—the biological, psychological, and social-cultural. This concept is introduced in Chapter 1 and revisited throughout the text. Readers will see evidence of our human kinship. Yet they will also better understand the dimensions of our diversity—our individual diversity, our gender diversity, and our cultural diversity. TABLE 2 provides a list of integrated coverage of the cross-cultural perspective on psychology. TABLE 3 (turn the page) lists the coverage of the psychology of women and men. Significant gender and cross-cultural examples and research are presented within the narrative. In addition, an abundance of photos showcases the diversity of cultures within North America and across the globe. These photos and their informative captions bring the pages to life, broadening students’ perspectives in applying psychological science to their own world and to the worlds across the globe.

| Coverage of culture and multicultural experience may be found on the following pages: |

| Academic achievement, pp. 247–249, 294 |

| Achievement motivation, p. B-4 |

| Adolescence, onset and end of, p. 92 |

| Aggression, p. 356 |

| Animal learning, p. 229 |

| Animal research, views on, pp. 21–22 |

| Beauty ideals, pp. 360–361 |

| Biopsychosocial approach, pp. 6–7, 85–86, 110–115, 374, 389 |

| Body image, p. 401 |

| Cluster migration, p. 265 |

| Cognitive development of children, p. 80 |

| Collectivism, pp. 331–333, 338, 342, 343 |

| Contraceptive use among teens, p. 118 |

| Crime and stress hormone levels, p. 404 |

| Cultural values |

| child-raising and, p. 85 |

| morality and, p. 88 |

| psychotherapy and, p. 423 |

| Culture |

| defined, p. 7 |

| emotional expression and, pp. 276–277 |

| intelligence test bias and, pp. 249–250 |

| the self and, pp. 331–333 |

| Deindividuation, p. 348 |

| Depression |

| and heart disease, p. 290 |

| and suicide, p. 392 |

| risk of, p. 393 |

| Developmental similarities across cultures, pp. 85–86 |

| Discrimination, pp. 350–351 |

| Dissociative identity disorder, p. 402 |

| Division of labor, p. 113 |

| Divorce rate, p. 98 |

| Dysfunctional behavior diagnoses, p. 372 |

| Eating disorders, p. 374 |

| Enemy perceptions, p. 365 |

| Exercise, p. 262 |

| Expressions of grief, p. 101 |

| Family environment, p. 90 |

| Family self, sense of, p. 85 |

| Father’s presence |

| pregnancy and, p. 119 |

| violence and, p. 356 |

| Flow, p. B-2 |

| Foot-in-the-door phenomenon, p. 340 |

| Framing, and organ donation, p. 224 |

| Fundamental attribution error, p. 338 |

| Gender roles, pp. 113, 128 |

| Gender |

| aggression and, p. 109 |

| communication and, pp. 109–110 |

| sex drive and, pp. 125–126 |

| General adaptation syndrome, p. 285 |

| Happiness, pp. 303–304, 305 |

| HIV/AIDS, pp. 117, 288 |

| Homosexuality, attitudes toward, p. 121 |

| Identity formation, pp. 89–90 |

| Individualism, pp. 331–333, 338, 343 |

| ingroup bias, p. 352 |

| moral development and, p. 88 |

| Intelligence, pp. 235–236 |

| group differences in, pp. 246–250 |

| Intelligence testing, p. 239 |

| Interracial dating, p. 350 |

| Job satisfaction, p. B-4 |

| Just-world phenomenon, p. 352 |

| Language development, pp. 231–232 |

| Leadership, pp. B-6–B-7 |

| Life satisfaction, p. 99 |

| Male-to-female violence, p. 356 |

| Mating preferences, pp. 126–127 |

| Mental disorders and stress, p. 374 |

| Mere exposure effect, p. 359 |

| Motivation, pp. 256–258 |

| Naturalistic observation, p. 14 |

| Need to belong, pp. 264–265 |

| Obedience, p. 345 |

| Obesity and sleep loss, p. 262 |

| Optimism, p. 294 |

| Ostracism, p. 265 |

| Parent-teen relations, p. 90 |

| Partner selection, p. 360 |

| Peer influence, p. 86 |

| on language development, p. 90 |

| Personal control, p. 292 |

| Personality traits, pp. 322–323 |

| Phobias, p. 381 |

| Physical attractiveness, pp. 360–361 |

| Poverty, explanations of, p. 339 |

| Power differences between men and women, p. 109 |

| Prejudice, pp. 352–353 |

| automatic, pp. 351–352 |

| contact, cooperation, and, p. 366 |

| forming categories, p. 353 |

| group polarization and, p. 348 |

| racial, p. 340 |

| subtle versus overt, pp. 350–351 |

| Prosocial behavior, p. 186 |

| Psychoactive drugs, pp. 381–382 |

| Psychological disorders, pp. 371, 374 |

| Racial similarities, pp. 248–249 |

| Religious involvement and longevity, p. 299 |

| Resilience, p. 432 |

| Risk assessment, p. 225 |

| Scapegoat theory, p. 352 |

| Schizophrenia, p. 398 |

| Self-esteem, p. 305 |

| Self-serving bias, p. 330 |

| Separation anxiety, p. 83 |

| Serial position effect, p. 205 |

| Social clock variation, p. 99 |

| Social influence, pp. 343, 345–346 |

| Social loafing, p. 347 |

| Social networking, p. 266 |

| Social trust, p. 84 |

| Social-cultural psychology, pp. 4, 6 |

| Stereotype threat, pp. 249–250 |

| Stereotypes, pp. 350, 352 |

| Stranger anxiety, p. 81 |

| Substance abuse, p. 389 |

| Substance abuse/addiction rates, p. 389 |

| Susto, p. 374 |

| Taijin-kyofusho, p. 374 |

| Taste preference, pp. 260–261 |

| Terrorism, pp. 224–225, 393, 339, 352, 354, 393 |

| Trauma, pp. 31 8, 421 |

| Universal expressions, p. 7 |

| Weight, p. 262 |

| Coverage of the psychology of women and men may be found on the following pages: |

| Age and decreased fertility, pp. 94–95 |

| Aggression, pp. 108–109, 354 |

| testosterone and, p. 354 |

| Alcohol use and sexual assault, p. 382 |

| Alcohol use disorder, p. 383 |

| Alcohol, women’s greater physical vulnerability, p. 383 |

| Attraction, pp. 358–363 |

| Beauty ideals, pp. 360–361 |

| Bipolar disorder, p. 392 |

| Body image, p. 401 |

| Depression, p. 393 |

| among girls, pp. 89–90 |

| higher vulnerability of women, p. 395 |

| seasonal patterns, p. 391 |

| Eating disorders, p. 401 |

| sexualization of girls and, p. 120 |

| Emotional expressiveness, pp. 275–276 |

| Emotion-detecting ability, p. 275 |

| Empathy, p. 276 |

| Father’s presence |

| pregnancy rates and, p. 119 |

| lower sexual activity and, p. 119 |

| Freud’s views on gender identity development, p. 314 |

| Gender, pp. 6–7 |

| anxiety and, p. 377 |

| biological influences on, pp. 110–112 |

| changes in society’s thinking about, pp. 107, 113, 128, 350 |

| social-cultural influences on, pp. 6–7, 113–115 |

| widowhood and, p. 100 |

| Gender differences, pp. 6–7, 108–110 |

| rumination and, p. 395 |

| evolutionary perspectives on, pp. 125–128 |

| intelligence and, pp. 246–247 |

| sexuality and, pp. 125–126 |

| Gender discrimination, pp. 350–351 |

| Gender identity, development of, pp. 113–115 |

| mismatch in transgendered individuals, p. 114 |

| Gender roles, p. 113 |

| Gender schema theory, p. 114 |

| Gender similarities, pp. 108–110 |

| Gender typing, p. 114 |

| HIV/AIDS, women’s vulnerability to, p. 117 |

| Hormones and sexual behavior, pp. 115–116 |

| Human sexuality, pp. 115–121 |

| Leadership styles, p. 109 |

| Learned helplessness, p. 395 |

| Life expectancy, p. 108 |

| Love |

| companionate, pp. 362–363 |

| passionate, pp. 361–362 |

| Marriage, pp. 97–98 |

| Mating preferences, pp. 126–127 |

| Maturation, pp. 86–87, 94 |

| Menarche, pp. 86, 92 |

| Menopause, p. 95 |

| Obedience, p. 344 |

| Physical attractiveness, pp. 359–360 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder, p. 379 |

| Puberty, p. 86 |

| early onset of, p. 92 |

| Relationship equity, p. 362 |

| Responses to stress, p. 286 |

| Schizophrenia, p. 398 |

| Sex, pp. 6, 115–117 |

| Sex and gender, p. 110 |

| Sex chromosomes, p. 111 |

| Sex drive, gender differences, pp. 118, 125 |

| Sex hormones, p. 110 |

| Sex-reassignment, p. 112 |

| Sexual activity and aging, p. 96 |

| Sexual activity, teen girls’ regret, p. 119 |

| Sexual arousal, gender and gay-straight differences, p. 123 |

| Sexual intercourse among teens, p. 117 |

| Sexual orientation, pp. 121–125 |

| Sexual response cycle, pp. 116–117 |

| Sexual response, alcohol-related expectation and, p. 384 |

| Sexual scripts, p. 357 |

| Sexuality, natural selection and, pp. 125–127 |

| Sexualization of girls, p. 120 |

| Sexually explicit media, pp. 119, 357 |

| Sexually transmitted infections, pp. 117–118 |

| Similarities and differences between men and women, pp. 108–110 |

| Social clock, p. 99 |

| Social connectedness, pp. 109–110 |

| Social power, p. 109 |

| Spirituality and longevity, p. 299 |

| Substance use disorder and the brain, p. 383 |

| Teen pregnancy, pp. 118–119 |

| Violent crime, pp. 108–109 |

| Vulnerability to psychological disorders, p. 108 |

| Weight loss, p. 263 |

| Women in psychology, pp. 2–3 |

3. We Operate With a Two-Track Mind (Dual Processing)

Today’s psychological science explores our dual-processing capacity. Our perception, thinking, memory, and attitudes all operate on two levels: the level of fully aware, conscious processing, and the behind-the-scenes level of unconscious processing. Students may be surprised to learn how much information we process outside of our awareness. Discussions of sleep (Chapter 2), perception (Chapter 5), cognition and emotion (Chapter 9), and attitudes and prejudice (Chapter 12) provide some particularly compelling examples of what goes on in our mind’s downstairs.

4. Psychology Explores Human Strengths as Well as Challenges

Students will learn about the many troublesome behaviors and emotions psychologists study, as well as the ways in which psychologists work with those who need help. Yet students will also learn about the beneficial emotions and traits that psychologists study, and the ways psychologists (some as part of the new positive psychology movement—turn the page to see TABLE 4) attempt to nurture those traits in others. After studying with this text, students may find themselves living improved day-to-day lives. See, for example, tips for better sleep in Chapter 2, parenting suggestions throughout Chapter 3, information to help with romantic relationships in Chapters 3, 4, 12, and elsewhere, and “Close-Up: Want to Be Happier?” in Chapter 10. Students may also find themselves doing better in their courses. See, for example, following this preface, “Time Management: Or, How to Be a Great Student and Still Have a Life”; “Improve Your Retention—and Your Grades” at the end of Chapter 1; “Improving Memory” in Chapter 7; and the helpful new study tools throughout the text based on the documented testing effect.

| Coverage of positive psychology topics can be found in the following chapters: | |

| Topic | Chapter |

|---|---|

| Altruism/compassion | 3, 8, 11, 12, 14 |

| Coping | 10 |

| Courage | 12 |

| Creativity | 7, 11, 12 |

| Emotional intelligence | 8, 12 |

| Empathy | 3, 6, 10, 12, 14 |

| Flow | App B |

| Gratitude | 9, 10, 12 |

| Happiness/life satisfaction | 3, 9, 10 |

| Humility | 12 |

| Humor | 10, 12 |

| Justice | 12 |

| Leadership | 9, 11, 12, App B |

| Love | 3, 4, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 |

| Morality | 3 |

| Optimism | 10, 11 |

| Personal control | 10 |

| Resilience | 3, 10, 12, 14 |

| Self-discipline | 3, 9, 11 |

| Self-efficacy | 10, 11 |

| Self-esteem | 9, 11 |

| Spirituality | 10, 12 |

| Toughness (grit) | 8, 9 |

| Wisdom | 2, 3, 8, 11, 12 |

Enhanced Clinical Psychology Coverage, Including Thorough DSM-5 Updating

Compared with other Myers texts, Psychology in Everyday Life has proportionately more coverage of clinical topics and a greater sensitivity to clinical issues throughout the text. For example, Chapter 13, Psychological Disorders, includes lengthy coverage of substance-related disorders, with guidelines for determining substance use disorder. The discussion of psychoactive drugs includes a special focus on alcohol and nicotine use. Clinical references, explanations, and examples throughout the text have been carefully updated to reflect DSM-5 changes. Chapter 13 includes an explanation of how disorders are now diagnosed, with illustrative examples throughout. See TABLE 5 for a listing of coverage of clinical psychology concepts and issues throughout the text.

| Coverage of clinical psychology may be found on the following pages: |

| Abused children, risk of psychological disorder among, p. 172 |

| Alcohol use and aggression, pp. 354–355 |

| Alzheimer’s disease, pp. 33, 245, 262 |

| Anxiety disorders, pp. 376–381 |

| Autism spectrum disorder, pp. 78–79, 108, 236 |

| Aversive conditioning, pp. 415–416 |

| Behavior modification, p. 416 |

| Behavior therapies, pp. 414–417 |

| Bipolar disorder, pp. 391–392 |

| Brain damage and memory loss, p. 206 |

| Brain scans, p. 38 |

| Brain stimulation therapies, pp. 427–429 |

| Childhood trauma, effect on mental health, pp. 83–84 |

| Client-analyst relationship in psychoanalysis, p. 411 |

| Client-centered therapy, p. 413 |

| Client-therapist relationship, p. 320 |

| Clinical psychologists, p. 5 |

| Cognitive therapies, pp. 396, 417–419 |

| eating disorders and, p. 417 |

| Culture and values in psychotherapy, pp. 423–424 |

| Depression: |

| adolescence and, p. 89 |

| heart disease and, p. 290 |

| homosexuality and, p. 122 |

| mood-memory connection and, p. 205 |

| outlook and, pp. 395–396 |

| self-esteem and, pp. 16–17, 89, 90–91, 178 |

| sexualization of girls and, p. 120 |

| social exclusion and, pp. 90–91 |

| unexpected loss and, pp. 100–101 |

| Dissociative and personality disorders, pp. 401–403 |

| Dissociative identity disorder, therapist’s role, p. 402 |

| Drug therapies, pp. 18, 424–427 |

| Drug treatment, p. 173 |

| DSM-5, pp. 374–375 |

| Eating disorders, pp. 389, 400–401 |

| Emotional intelligence, p. 238 |

| Evidence-based clinical decision making, p. 422 |

| Exercise, therapeutic effects of, pp. 296–297, 426, 430 |

| Exposure therapies, pp. 414–415 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder, p. 377 |

| Grief therapy, p. 101 |

| Group and family therapies, pp. 419–420 |

| Historical treatment of mental illness, pp. 372, 410 |

| Humanistic therapies, pp. 412–414 |

| Hypnosis and pain relief, pp. 156–157 |

| Intelligence scales and stroke rehabilitation, p. 240 |

| Lifestyle change, therapeutic effects of, pp. 430–431 |

| Loss of a child, psychiatric hospitalization and, p. 101 |

| Major depressive disorder, pp. 390–391 |

| Medical model of mental disorders, pp. 373–374 |

| Mood disorders, pp. 390–396 |

| Neurotransmitter imbalances and related disorders, p. 33 |

| Nurturing strengths, p. 320 |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder, p. 378 |

| Operant conditioning, pp. 416–417 |

| Ostracism, pp. 265–266 |

| Panic disorder, p. 377 |

| Personality inventories, p. 324 |

| Personality testing, pp. 316–317 |

| Phobias, pp. 377–378 |

| Physical and psychological treatment of pain, pp. 155–156 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder, pp. 378–379 |

| Psychiatric labels and bias, p. 375 |

| Psychoactive drugs, types of, pp. 424–427 |

| Psychoanalysis, pp. 410–412 |

| Psychodynamic theory, pp. 315–316 |

| Psychodynamic therapy, p. 412 |

| Psychological disorders, pp. 371–404 |

| are those with disorders dangerous?, p. 376 |

| classification of, pp. 374–375 |

| gender differences in, p. 108 |

| preventing, and building resilience, pp. 431–432 |

| Psychotherapy, pp. 410–424 |

| effectiveness of, pp. 420–423 |

| Rorschach inkblot test, p. 316 |

| Savant syndrome, p. 236 |

| Schizophrenia, pp. 397–400 |

| parent-blaming and, p. 91 |

| risk of, pp. 399–400 |

| Self-actualization, p. 319 |

| Self-injury, pp. 392–393 |

| Sex reassignment surgery, p. 112 |

| Sleep disorders, pp. 58–60, 374 |

| Spanked children, risk for aggression and depression among, p. 178 |

| Substance use and addictive disorders, pp. 381–390 |

| Suicide, pp. 392–393 |

| Testosterone replacement therapy, pp. 115–116 |

| Tolerance, withdrawal, and addiction, p. 382 |

Everyday Life Applications

Throughout this text, as its title suggests, we relate the findings of psychology’s research to the real world. This edition includes:

- chapter-ending “In Your Everyday Life” questions, helping students make the concepts more meaningful (and memorable).

- fun notes and quotes in small boxes throughout the text, applying psychology’s findings to sports, literature, world religions, and music.

- “Assess Your Strengths” personal self-assessments online in LaunchPad, allowing students to actively apply key principles to their own experiences.

- an emphasis throughout the text on critical thinking in everyday life, including the “Statistical Reasoning in Everyday Life” appendix, helping students to become more informed consumers and everyday thinkers.

See inside the front and back covers for a listing of students’ favorite 50 of this text’s applications to everyday life.

APA Assessment Tools

In 2011, the American Psychological Association (APA) approved the new Principles for Quality Undergraduate Education in Psychology. These broad-based principles and their associated recommendations were designed to “produce psychologically literate citizens who apply the principles of psychological science at work and at home.” (See www.apa.org/education/undergrad/principles.aspx.)

APA’s more specific 2013 Learning Goals and Outcomes, from their Guidelines for the Undergraduate Psychology Major, Version 2.0, were designed to gauge progress in students graduating with psychology majors. (See www.apa.org/ed/precollege/about/psymajor-guidelines.pdf.) Many psychology departments use these goals and outcomes to help establish their own benchmarks for departmental assessment purposes.

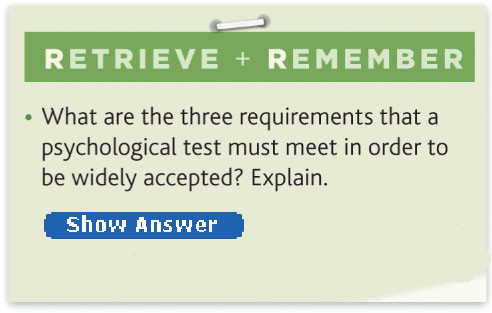

Some instructors are eager to know whether a given text for the introductory course helps students get a good start at achieving these APA benchmarks. TABLE 6 on the next page offers a sample, using the first Principle, to illustrate how nicely Psychology in Everyday Life, Third Edition, corresponds to the 2011 APA Principles. (For a complete correlation guide to all five of the 2011 APA Principles, see http://tinyurl.com/m62dr95.) Turn the page to see TABLE 7, which outlines the way Psychology in Everyday Life, Third Edition, could help you to address the 2013 APA Learning Goals and Outcomes in your department.

| Quality Principle 1: Students are responsible for monitoring and enhancing their own learning. | |

|---|---|

| APA Recommendations | Relevant Coverage or Feature From Psychology in Everyday Life, Third Edition |

| 1. Students know how to learn. |

|

| 2. Students assume increasing responsibility for their own learning. |

|

| 3. Students take advantage of the rich diversity that exists in educational institutions and learn from individuals who are different from them. |

|

| 4. Students are responsible for seeking advice for academic tasks, such as selecting courses in the approved sequence that satisfy the institution’s requirements for the major and general education. They are also responsible for seeking advice about planning for a career that is realistic and tailored to their individual talents, aspirations, and situations. |

|

| 5. Students strive to become psychologically literate citizens. |

|

In addition, an APA working group in 2013 drafted guidelines for Strengthening the Common Core of the Introductory Psychology Course (http://tinyurl.com/14dsdx5). Their goals are to “strike a nuanced balance providing flexibility yet guidance.” The group noted that “a mature science should be able to agree upon and communicate its unifying core while embracing diversity.”

MCAT Will Include Psychology Starting in 2015

Beginning in 2015, the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) is devoting 25 percent of its questions to the “Psychological, Social, and Biological Foundations of Behavior,” with most of those questions coming from the psychological science taught in introductory psychology courses. From 1977 to 2014, the MCAT focused on biology, chemistry, and physics. Hereafter, reports the new Preview Guide for MCAT 2015, the exam will also recognize “the importance of socio-cultural and behavioral determinants of health and health outcomes.” The exam’s new psychology section covers the breadth of topics in this text. For example, turn the page to see TABLE 8, which outlines the precise correlation between the topics in this text’s Sensation and Perception chapter and the corresponding portion of the MCAT exam. For a complete pairing of the new MCAT psychology topics with this book’s contents, see www.worthpublishers.com/MyersPEL3e.

| MCAT 2015 | Myers, Psychology in Everyday Life, Third Edition, Correlations | |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Content Category 6e: Sensing the environment | Page Number | |

| Sensory Processing | Sensation and Perception | 132–165 |

| Sensation | Basic Principles of Sensation and Perception | 134–139 |

| Thresholds | Thresholds | 135–137 |

| Signal detection theory | Difference Thresholds | 136 |

| Sensory adaptation | Sensory Adaptation | 137–138 |

| Sensory receptors transduce stimulus energy and transmit signals to the central nervous system. | From Outer Energy to Inner Brain Activity (transduction key term) | 134–135 |

| Sensory pathways | Vision | 139–142 |

| Hearing | 151–154 | |

| Understanding Pain | 154–155 | |

| Taste | 157–158 | |

| Smell | 158–159 | |

| Body Position and Movement | 159–160 | |

| Types of sensory receptors | The Eye | 141–142 |

| Decoding Sound Waves | 152–153 | |

| Understanding Pain | 154–155 | |

| Taste | 157–158 | |

| Smell | 158–158 | |

| Body Position and Movement | 159–160 | |

| Table 5.3, Summarizing the Senses | 160 | |

| The cerebral cortex controls voluntary movement and cognitive functions. | Functions of the Cortex | 43–47 |

| Information processing in the cerebral cortex | The Cerebral Cortex | 42–47 |

| Our Divided Brain | 47–50 | |

| Vision | Vision | 139–151 |

| Structure and function of the eye | The Eye | 140–142 |

| Visual processing | Visual Information Processing | 142–143 |

| Visual pathways in the brain | FIGURE 5.15, Pathway from the eyes to the visual cortex | 143 |

| Parallel processing | Parallel processing | 143 |

| Feature detection | Feature detection | 142–143 |

| Hearing | Hearing | 151–154 |

| Auditory processing | Hearing | 151–154 |

| Auditory pathways in the brain | Sound Waves: From the Environment Into the Brain | 151–152 |

| Perceiving loudness and pitch | Sound Waves: From the Environment Into the Brain | 151–152 |

| FIGURE 5.10, The physical properties of waves | 140 | |

| Locating sounds | How Do We Locate Sounds? | 153–154 |

| Sensory reception by hair cells | Decoding Sound Waves | 152–153 |

| Table 5.3, Summarizing the Senses | 160 | |

| Other Senses | Touch, Taste, Smell, Body Position and Movement | 154–160 |

| Somatosensation | Touch | 154–157 |

| Sensory systems in the skin | Sensory Functions (of the cortex) | 45 |

| Touch | 154 | |

| Tactile pathways in the brain | Somatosensory cortex | 44, 45 |

| Table 5.3, Summarizing the Senses | 160 | |

| Types of pain | Pain | 154–155 |

| Factors that influence pain | Understanding Pain | 154–155 |

| Controlling Pain | 155–156 | |

| Hypnosis and Pain Relief | 156–157 | |

| Taste | Taste | 157–158 |

| Taste buds/chemoreceptors that detect specific chemicals in the environment | Taste | 157–158 |

| Table 5.3, Summarizing the Senses | 160 | |

| Gustatory pathways in the brain | FIGURE 5.29, Taste, Smell, and Memory | 158 |

| Smell | Smell | 158–159 |

| Olfactory cells/chemoreceptors that detect specific chemicals in the environment | Smell | 158–159 |

| Table 5.3, Summarizing the Senses | 160 | |

| Pheromones | Smell of sex-related hormones | 123–125 |

| Olfactory paths in the brain | FIGURE 5.29, Taste, Smell, and Memory | 158 |

| Role of smell in perception of taste | Sensory Interaction | 160–161 |

| Perception | Sensation and Perception | 132–165 |

| Bottom-up/Top-down processing | Basic Principles of Sensation and Perception (bottom-up and top-down processing key terms) | 134 |

| Perceptual organization (i.e., depth, form, motion, constancy) | Visual Organization: Form Perception, Depth Perception (including Relative Motion), Perceptual Constancy | 145–150 |

| FIGURE 5.16, Parallel processing (of motion, form, depth, color) | 143 | |

| Gestalt principles | Visual Organization: Form Perception (gestalt key term) | 145–146 |

Next-Generation Multimedia

Psychology in Everyday Life, Third Edition, boasts impressive multimedia options. For more information about any of these choices, visit Worth Publishers’ online catalog at www.worthpublishers.com.

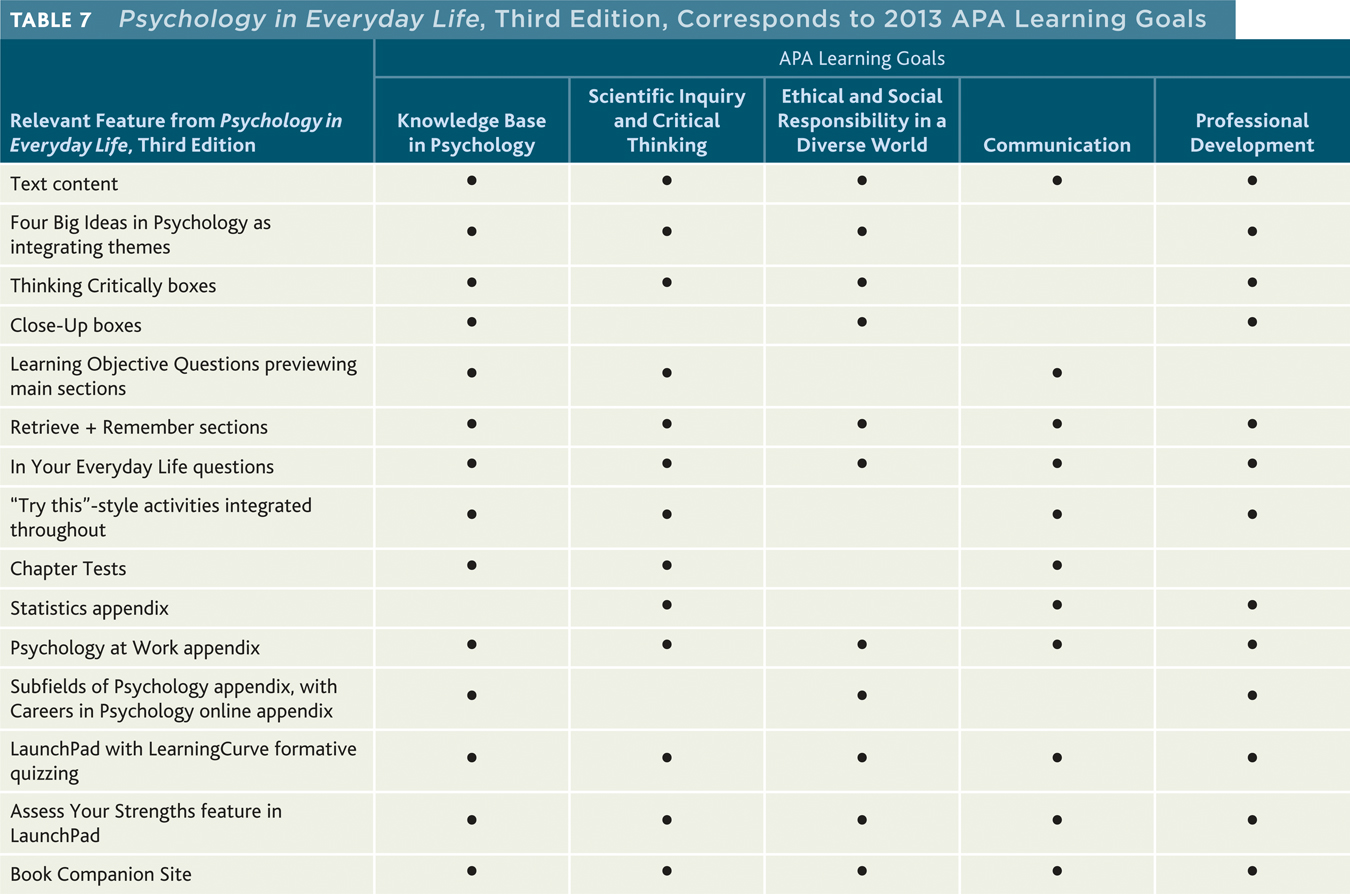

LaunchPad With LearningCurve Quizzing and Assess Your Strengths Activities

LaunchPad offers a set of prebuilt assignments, carefully crafted by a group of instructional designers and instructors with an abundance of teaching experience as well as deep familiarity with Worth content. Each LaunchPad unit contains videos, activities, and formative assessment pieces to build student understanding for each topic, culminating with a randomized summative quiz to hold students accountable for the unit. Assign units in just a few clicks, and find scores in your gradebook upon submission. LaunchPad appeals not only to instructors who have been interested in adding an online component to their course but haven’t been able to invest the time, but also to experienced online instructors curious to see how other colleagues might scaffold a series of online activities. Customize units as you wish, adding and dropping content to fit your course. (See FIGURE 3.)

LearningCurve combines adaptive question selection, personalized study plans, immediate and valuable feedback, and state-of-the-art question analysis reports. Based on the latest findings from learning and memory research, LearningCurve’s game-like nature keeps students engaged while helping them learn and remember key concepts.

With Assess Your Strengths activities, students may take inventories and questionnaires developed by researchers across psychological science. These self-assessments allow students to apply psychology’s principles to their own lives and experiences. After taking each self-assessment, students will find additional information about the strength being tested (for example, personal growth initiative, sleep quality, empathizing/systemizing, intrinsic/extrinsic motivation, mindfulness, self-control, and hope), as well as tips for nurturing that strength more effectively in their own lives.

Faculty Support and Student Resources

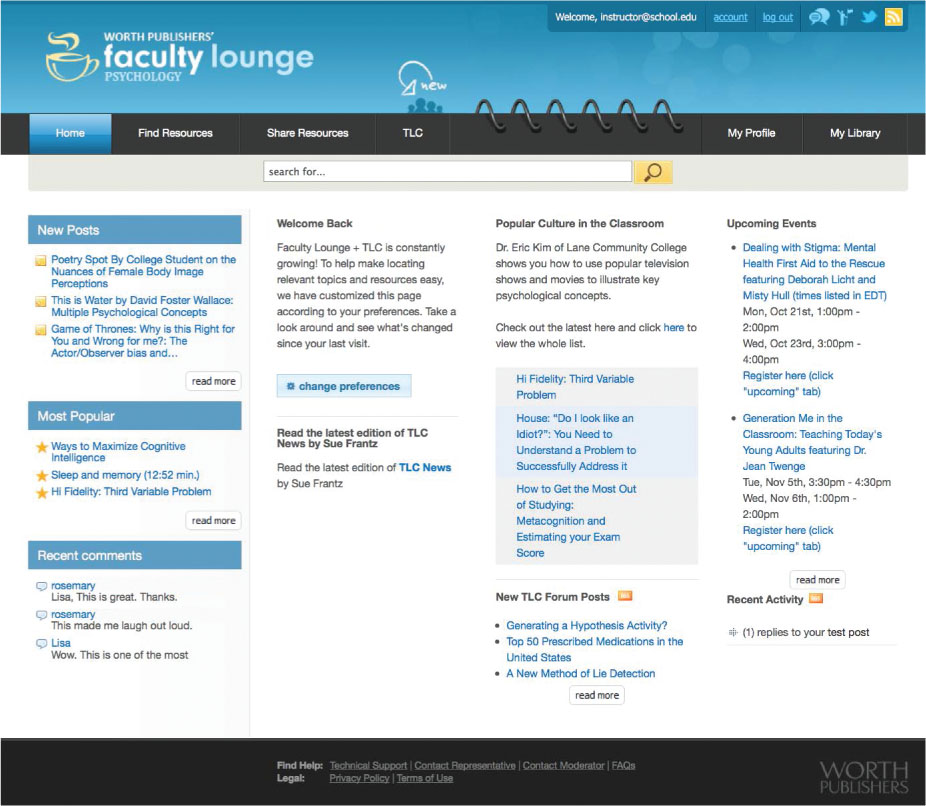

- Faculty Lounge—http://psych.facultylounge.worthpublishers.com—(see FIGURE 4 on the next page) is an online gathering place to find and share favorite teaching ideas and materials, including videos, animations, images, PowerPoint® slides and lectures, news stories, articles, web links, and lecture activities. Includes publisher-as well as peer-provided resources—all faculty-reviewed for accuracy and quality.

Sample from our Faculty Lounge site (http://psych.facultylounge.worthpublishers.com)

Sample from our Faculty Lounge site (http://psych.facultylounge.worthpublishers.com) - Instructor’s Media Guide for Introductory Psychology

- Enhanced Course Management Solutions (including course cartridges)

- e-Book in various available formats, with embedded Concepts in Action

- Book Companion Site

Video and Presentation

- The Worth Video Anthology for Introductory Psychology is a complete collection, all in one place, of all of our video clips. The set is accompanied by its own Faculty Guide.

- Interactive Presentation Slides for Introductory Psychology is an extraordinary series of PowerPoint® lectures. This is a dynamic, yet easy-to-use way to engage students during classroom presentations of core psychology topics. This collection provides opportunities for discussion and interaction, and includes an unprecedented number of embedded video clips and animations.

Assessment

- LearningCurve summative quizzing

- Printed Test Banks

- Diploma Computerized Test Banks

- Online Quizzing

- i•clicker Radio Frequency Classroom Response System

- Instructor’s Resources

- Lecture Guides

- Study Guide

- Pursuing Human Strengths: A Positive Psychology Guide

- Critical Thinking Companion, Second Edition

- Psychology and the Real World: Essays Illustrating Fundamental Contributions to Society. This project of the FABBS Foundation brought together a virtual “Who’s Who” of contemporary psychological scientists to describe—in clear, captivating ways—the research they have passionately pursued and what it means to the “real world.” Each contribution is an original essay written for this project.

In Appreciation

Aided by input from thousands of instructors and students over the years, this has become a better, more effective, more accurate book than two authors alone (these authors at least) could write. Our indebtedness continues to the innumerable researchers who have been so willing to share their time and talent to help us accurately report their research.

For this edition, we especially appreciated Jim Foley’s (Wooster, Ohio) detailed consulting review of the clinical materials, primarily for the purpose of updating for the DSM-5.

Our gratitude extends to the colleagues who contributed criticism, corrections, and creative ideas related to the content, pedagogy, and format of this new edition and its two predecessors. For their expertise and encouragement, and the gift of their time to the teaching of psychology, we thank the reviewers and consultants listed here.

First and Second Edition Reviewers

Tricia Alexander, Long Beach City College

Pamela Ansburg, Metropolitan State College of Denver

Randy Arnau, University of Southern Mississippi

Stacy Bacigalupi, Mount San Antonio College

Kimberly Bays-Brown, Ball State University

Alan Beauchamp, Northern Michigan University

Richard Bernstein, Broward College—South Campus

Diane Bogdan, CUNY: Hunter College

Robert Boroff, Modesto Junior College

Christia Brown, University of Kentucky

Alison Buchanan, Henry Ford Community College

Norma Caltagirone, Hillsborough Community College—Ybor City

Nicole Judice Campbell, University of Oklahoma

David Carlston, Midwestern State University

Kimberly Christopherson, Morningside College

Diana Ciesko, Valencia Community College

TaMetryce Collins, Hillsborough Community College

Patricia Crowe, Hawkeye College

Jennifer Dale, Community College of Aurora

David Devonis, Graceland University

George Diekhoff, Midwestern State University

Michael Drissman, Macomb Community College

Laura Duvall, Heartland Community College

Jennifer Dyck, SUNY College at Fredonia

Laura Engleman, Pikes Peak Community College

Warren Fass, University of Pittsburgh

Vivian Ferry, Community College of Rhode Island

Elizabeth Freeman-Young, Bentley College

Ann Fresoli, Lehigh Carbon Community College

Ruth Frickle, Highline Community College

Lenore Frigo, Shasta College

Gary Gargano, Merced College

Jo Anne Geron, Antioch University

Stephanie Grant, Southern Nazarene University

Raymond Green, The Honors College of Texas

Sandy Grossman, Clackamas Community College

Lisa Gunderson, Sacramento City College

Rob Guttentag, University of North Carolina—Greensboro

Gordon Hammerle, Adrian College

Mark Hartlaub, Texas A&M University

Sheryl Hartman, Miami Dade College

Brett Heintz, Delgado Community College

Suzy Horton, Mesa Community College

Alishia Huntoon, Oregon Institute of Technology

Cindy Hutman, Elgin Community College

Laurene Jones, Mercer County Community College

Charles “Ed” Joubert, University of North Alabama

Deana Julka, University of Portland

Richard Kandus, Mount San Jacinto College, Menifree

Elizabeth Kennedy, University of Akron

Norm Kinney, Southeast Missouri University

Gary Klatsky, SUNY Oswego State University

Dan Klaus, Community College of Beaver County

Laurel Krautwurst, Blue Ridge Community College

Juliana Leding, University of North Florida

Gary Lewandowski, Monmouth University

Alicia Limke, University of Central Oklahoma

Leslie Linder, Bridgewater State College

Chris Long, Ouachita Baptist University

Martha Low, Winston-Salem State University

Mark Ludorf, Stephen F. Austin State University

Brian MacKenna-Rice, Middlesex Community College

Vince Markowski, University of Southern Maine

Dawn McBride, Illinois State University

Marcia McKinley, Mount St. Mary’s University

Tammy Menzel, Mott Community College

Leslie Minor-Evans, Central Oregon Community College

Ronald Mossler, Los Angeles Valley College

Maria Navarro, Valencia Community College

Daniel Nelson, North Central University

David Neufeldt, Hutchinson Community College

Peggy Norwood, Community College of Aurora

Fabian Novello, Clark State Community College

Fawn Oates, Red Rocks Community College

Ginger Osborne, Santa Ana College

Randall Osborne, Texas State University—San Marcos

Carola Pedreschi, Miami-Dade College, North Campus

Jim Previte, Victor Valley College

Sean Reilley, Morehead State University

Tanya Renner, Kapi’olani Community College

Vicki Ritts, St. Louis Community College—Meramec

Dave Rudek, Aurora University

R. Steven Schiavo, Wellesley College

Cynthia Selby, California State University—Chico

Jennifer Siciliani, University of Missouri—St. Louis

Barry Silber, Hillsborough Community College

Madhu Singh, Tougaloo College

Alice Skeens, University of Toledo

Jason Spiegelman, Towson University & Community College of Baltimore County

Anna-Marie Spinos, Aurora University

Betsy Stern, Milwaukee Area Technical College

Ruth Thibodeau, Fitchburg State College

Eloise Thomas, Ozarks Technical Community College

Susan Troy, Northeast Iowa Community College

Michael Verro, Empire State College

Jacqueline Wall, University of Indianapolis

Marc Wayner, Hocking College

Diane Webber, Curry College

Richard Wedemeyer, Rose State College

Peter Wooldridge, Durham Technical Community College

John Wright, Washington State University

Gabriel Ybarra, University of North Florida

Third Edition Reviewers

Diane Agresta, Washtenaw Community College

Barb Angleberger, Frederick Community College

Cheryl Armstrong, Fitchburg State College

Jamie Arnold, Letourneau University

Sandra Arntz, Carroll College

Grace Austin, Sacramento City College

Stephen Balzac, Wentworth Institute of Technology

Chip (Charles) Barker, Olympic College

Elaine Barry, Pennsylvania State University—Fayette Campus

Karen Beale, Maryville College

Michael Bogue, Mohave Community College—Bullhead

Karen Brakke, Spellman College

Christina Bresner, Champlain College, Lennoxville

Carrie Bulger, Quinnipiac University

Sarah Calabrese, Yale University

Jennifer Colman, Champlain College

Victoria Cooke, Erie Community College

Daniel Dickman, Ivy Tech Community College—Evansville

Kevin Dooley, Grossmont College

Mimi Dumville, Raritan Valley Community College

Julie Ehrhardt, Bristol Community College—Bedford Campus

Traci Elliott, Alvin Community College

Mark Evans, Tarrant County College—Northwest

Brian Follick, California State University—Fullerton

Paula Frioli-Peters, Truckee Meadows Community College

Deborah Garfin, Georgia State University

Karla Gingerich, Colorado State University

Darah E. Granger, Florida State College at Jacksonville—Kent

Carrie Hall, Miami University

Christina Hawala, DeVry University

John Haworth, Chattanooga State Technical Community College

Toni Henderson, Langara College

Mary Horton, Mesa Community College

Bernadette Jacobs, Santa Fe Community College

Joan Jensen, Central Piedmont Community College

Patricia Johnson, Craven Community College—Havelock Campus

Lynnel Kiely, City Colleges of Chicago—Harry S. Truman College

Jennifer Klebaur, Central Piedmont Community College—North Campus

Sarah Kranz, Letourneau University

Michael Lantz, Kent State University at Trumbull

Mary Livingston, Louisiana Tech University

Donald Lucas, Northwest Vista College

Molly Lynch, Northern Virginia Community College

Brian MacKenna-Rice, Middlesex Community College

Cheree Madison, Lanier Technical College

Robert Martinez, Northwest Vista College

David McAllister, Salem State College

Gerald McKeegan, Bridgewater College

Michelle Merwin, University of Tennessee—Martin

Shelly Metz, Central New Mexico Community College

Erin Miller, Bridgewater College

Barbara Modisette, Letourneau University

Maria A. Murphy, Florida State College at Jacksonville—North

Jake Musgrove, Broward College—Central Campus

Robin Musselman, Lehigh Carbon Community College

Dana Narter, The University of Arizona

Robert Nelson, Montgomery Community College

Caroline Olko, Nassau Community College

Maria Ortega, Washtenaw Community College

Lee Osterhout, University of Washington

Terry Pettijohn, Ohio State University—Marion Campus

Frieda Rector, Yosemite University

Rebecca Regeth, California University of Pennsylvania

Miranda Richmond, Northwest Vista College

Hugh Riley, Baylor University

Craig Rogers, Campbellsville University

Nicholas Schmitt, Heartland Community College

Christine Shea-Hunt, Kirkwood Community College

Brenda Shook, National University

David Simpson, Carroll University

Starlette Sinclair, Columbus State University

Gregory Smith, University of Kentucky

Eric Stephens, University of the Cumberlands

Colleen Sullivan, Worcester State University

Melissa Terlecki, Cabrini College

Lawrence Voight, Washtenaw Community College

Benjamin Wallace, Cleveland State University

David Williams, Spartanburg Community College

Melissa (Liz) Wright, Northwest Vista College

We were pleased to be supported by a 2012/2013 Content Advisory Board, which helped guide the development of this new edition of Psychology in Everyday Life as well as our other introductory psychology titles. For their helpful input and support, we thank

Barbara Angleberger, Frederick Community College

Chip (Charles) Barker, Olympic College

Mimi Dumville, Raritan Valley Community College

Paula Frioli-Peters, Truckee Meadows Community College

Deborah Garfin, Georgia State University

Karla Gingerich, Colorado State University

Toni Henderson, Langara College

Bernadette Jacobs, Santa Fe Community College

Mary Livingston, Louisiana Tech University

Molly Lynch, Northern Virginia Community College

Shelly Metz, Central New Mexico Community College

Jake Musgrove, Broward College—Central Campus

Robin Musselman, Lehigh Carbon Community College

Dana Narter, The University of Arizona

Lee Osterhout, University of Washington

Nicholas Schmitt, Heartland Community College

Christine Shea-Hunt, Kirkwood Community College

Brenda Shook, National University

Starlette Sinclair, Columbus State University

David Williams, Spartanburg Community College

Melissa (Liz) Wright, Northwest Vista College

We are also grateful for the instructors and students who took the time to offer feedback over the phone, in an online survey, or at one of our face-to-face focus groups. Over 1000 instructors responded to surveys related to depth of coverage and concept difficulty levels.

Seventeen instructors offered helpful and detailed feedback on our design:

Sandra Arntz, Carroll University

Christine Browning, Victory University

Christina Calayag, North Central University

Tametryce Collins, Hillsborough Community College—Brandon Campus

Traci Elliott, Alvin Community College

Betsy Ingram-Diver, Lake Superior College

Bernadette Jacobs, Santa Fe Community College

Patricia Johnson, Craven Community College—Havelock Campus

Todd Joseph Allen, Hillsborough Community College

Donald Lucas, Northwest Vista College

Susie Moerschbacher, Polk State College

Marcia Seddon, Indian Hills Community College

Christine Shea-Hunt, Kirkwood Community College

Brenda Shook, National University

Beth Smith, Hillsborough Community College—Brandon Campus

Heather Thompson, College of Western Idaho

Melissa (Liz) Wright, Northwest Vista College

Nine instructors coordinated input from 131 of their students about our text design:

Sandra Arntz, Carroll University

Christina Calayag, North Central University

Tametryce Collins, Hillsborough Community College—Brandon Campus

Traci Elliott, Alvin Community College

Patricia Johnson, Craven Community College—Havelock Campus

Marcia Seddon, Indian Hills Community College

Christine Shea-Hunt, Kirkwood Community College

Heather Thompson, College of Western Idaho

Melissa (Liz) Wright, Northwest Vista College

We consulted with eight instructors by phone for lengthy conversations about key features:

Christina Calayag, North Central University

Tametryce Collins, Hillsborough Community College

Patricia Johnson, Craven Community College—Havelock Campus

Todd Allen Joseph, Hillsborough Community College

Lynne Kennette, Wayne State University

Christine Shea-Hunt, Kirkwood Community College

Heather Thompson, College of Western Idaho

Melissa (Liz) Wright, Northwest Vista College

We gathered extensive written input about the text and its features from 38 students at North Central College (thanks to the coordinating efforts of Christina Calayag). We hosted three student focus groups at the College of Western Idaho (coordinated by Heather Thompson), Hillsborough Community College (coordinated by Todd Allen Joseph), and Kirkwood Community College (coordinated by Christine Shea-Hunt).

We also involved students in a survey to determine level of difficulty of key concepts. A total of 277 students from the following schools participated:

Brevard Community College

Community College of Baltimore County

Florida International University

Millsaps College

Salt Lake Community College

And we involved a group of helpful students in reviewing the application questions for this new edition:

Bianca Arias, City College of New York

Brigitte Black, College of St. Benedict

Antonia Brune, Service High School

Gabriella Brune, College of St. Benedict

Peter Casale, Hofstra University

Alex Coumbis, Fordham University

Julia Elliott, Hofstra University

Megan Lynn Garrett, Ramapo College

Curran Kelly, University of Houston Downtown

Stephanie Kroll, SUNY Geneseo

Aaron Mehlenbacher, SUNY Geneseo

Brendan Morrow, Hofstra University

Kristina Persaud, Colgate University

Steven Pignato, St. John’s University

Ryan Sakhichand, ITT Tech Institute

Carlisle Sargent, Clemson University

Josh Saunders, The College of New Jersey

At Worth Publishers a host of people played key roles in creating this third edition.

Although the information gathering is never ending, the formal planning began as the author-publisher team gathered for a two-day retreat. This happy and creative gathering included John Brink, Thomas Ludwig, Richard Straub, and me [DM] from the author team, along with my assistants Kathryn Brownson and Sara Neevel. We were joined by Worth Publishers executives Tom Scotty, Elizabeth Widdicombe, Catherine Woods, and Craig Bleyer; editors Christine Brune, Kevin Feyen, Nancy Fleming, Tracey Kuehn, Betty Probert, and Trish Morgan; artistic director Babs Reingold; sales and marketing colleagues Tom Kling, Carlise Stembridge, John Britch, Lindsay Johnson, Cindi Weiss, Kari Ewalt, Mike Howard, and Matt Ours; and special guests Amy Himsel (El Camino Community College), Jennifer Peluso (Florida Atlantic University), Charlotte vanOyen Witvliet (Hope College), and Jennifer Zwolinski (University of San Diego). The input and brainstorming during this meeting of minds gave birth, among other things, to the study aids in this edition, the carefully revised clinical coverage, the revised organization, and the refreshing new design.

Publisher Kevin Feyen is a valued team leader, thanks to his dedication, creativity, and sensitivity. Catherine Woods, Vice President, Editing, Design, and Media, helped construct and execute the plan for this text and its supplements. Elizabeth Block, Anthony Casciano, and Nadina Persaud coordinated production of the huge media and print supplements package for this edition. Betty Probert efficiently edited and produced the print supplements and, in the process, also helped fine-tune the whole book. Nadina also provided invaluable support in commissioning and organizing the multitude of reviews, mailing information to professors, and handling numerous other daily tasks related to the book’s development and production. Charles Yuen did a splendid job of laying out each page. Robin Fadool, Bianca Moscatelli, and Donna Ranieri worked together to locate the myriad photos.

Tracey Kuehn, Director of Print and Digital Development, displayed tireless tenacity, commitment, and impressive organization in leading Worth’s gifted artistic production team and coordinating editorial input throughout the production process. Senior Project Editor Jane O’Neill and Production Manager Sarah Segal masterfully kept the book to its tight schedule, and Art Director Barbara Reingold skillfully directed creation of the beautiful new design and art program. Production Manager Stacey Alexander, along with Supplements Production Editor Edgar Bonilla, did their usual excellent work of producing the many supplements.

As you can see, although this book has two authors it is a team effort. A special salute is due our two book development editors, who have invested so much in creating Psychology in Everyday Life. My [DM] longtime editor Christine Brune saw the need for a very short, accessible, student-friendly introductory psychology text, and she energized and guided the rest of us in bringing her vision to reality. Development editor Nancy Fleming is one of those rare editors who is gifted at “thinking big” about a chapter while also applying her sensitive, graceful, line-by-line touches. Her painstaking, deft editing was a key part of achieving the hoped-for brevity and accessibility. In addition, Trish Morgan joined our editorial team for both the planning and late-stage editorial work, and once again amazed me with her meticulous eye, impressive knowledge, and deft editing. And Deborah Heimann did an excellent job with the copyediting.

To achieve our goal of supporting the teaching of psychology, this teaching package not only must be authored, reviewed, edited, and produced, but also made available to teachers of psychology. For their exceptional success in doing that, our author team is grateful to Worth Publishers’ professional sales and marketing team. We are especially grateful to Executive Marketing Manager Kate Nurre, Marketing Manager Lindsay Johnson, and National Psychology and Economics Consultant Tom Kling, both for their tireless efforts to inform our teaching colleagues of our efforts to assist their teaching, and for the joy of working with them.

At Hope College, the supporting team members for this edition included Kathryn Brownson, who researched countless bits of information and proofed hundreds of pages. Kathryn has become a knowledgeable and sensitive adviser on many matters, and Sara Neevel has become our high-tech manuscript developer, par excellence.

Again, I [DM] gratefully acknowledge the influence and editing assistance of my writing coach, poet Jack Ridl, whose influence resides in the voice you will be hearing in the pages that follow. He, more than anyone, cultivated my delight in dancing with the language, and taught me to approach writing as a craft that shades into art.

After hearing countless dozens of people say that this book’s supplements have taken their teaching to a new level, we reflect on how fortunate we are to be a part of a team in which everyone has produced on-time work marked by the highest professional standards. For their remarkable talents, their long-term dedication, and their friendship, we thank John Brink, Thomas Ludwig, Richard Straub, and Jennifer Peluso.

Finally, our gratitude extends to the many students and instructors who have written to offer suggestions, or just an encouraging word. It is for them, and those about to begin their study of psychology, that we have done our best to introduce the field we love.

. . .

The day this book went to press was the day we started gathering information and ideas for the next edition. Your input will influence how this book continues to evolve. So, please, do share your thoughts.

Hope College

Holland, Michigan 49422-9000 USA

University of Kentucky

Lexington, Kentucky 40506-0044 USA