Time Management: Or, How to Be a Great Student and Still Have a Life

|

Time Management |

Desislava Draganova/Alamy

|

|

Or, How to Be a Great Student and Still Have a Life |

||

|

Richard O. Straub, University of Michigan, Dearborn |

||

How Are You Using Your Time Now?

Design a Better SchedulePlan the Term

Plan Your Week

- CLOSE-UP: More Tips for Effective Scheduling

Make Every Minute of Your Study Time Count- Take Useful Class Notes

- Create a Study Space That Helps You Learn

- Set Specific, Realistic Daily Goals

- Use SQ3R to Help You Master This Text

- Don’t Forget About Rewards!

- Take Useful Class Notes

Do You Need to Revise Your New Schedule?- Are You Doing Well in Some Courses But Not in Others?

- Have You Received a Poor Grade on a Test?

- Are You Trying to Study Regularly for the First Time and Feeling Overwhelmed?

- Are You Doing Well in Some Courses But Not in Others?

We all face challenges in our schedules. Some of you may be taking midnight courses, others squeezing in an online course between jobs or after putting children to bed at night. Some of you may be veterans using military benefits to jump-start a new life. Just making the standard transition from high school to college can be challenging enough.

How can you balance all of your life’s demands and be successful? Time management. Manage the time you have so that you can find the time you need.

In this section, I will outline a simple, four-step process for improving the way you make use of your time.

- Keep a time-use diary to understand how you are using your time. You may be surprised at how much time you’re wasting.

- Design a new schedule for using your time more effectively.

- Make the most of your study time so that your new schedule will work for you.

- If necessary, refine your new schedule, based on what you’ve learned.

How Are You Using Your Time Now?

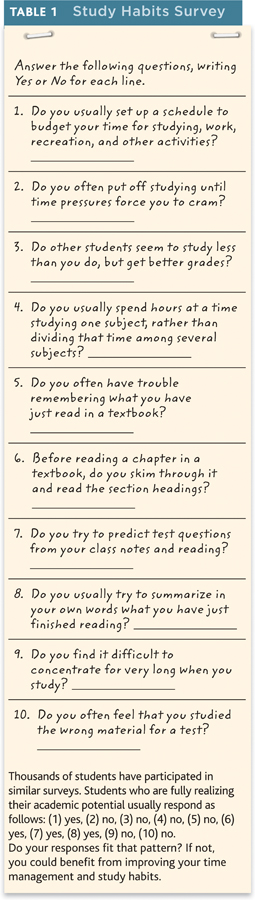

Although everyone gets 24 hours in the day and seven days in the week, we fill those hours and days with different obligations and interests. If you are like most people, you probably use your time wisely in some ways, and not so wisely in others. Answering the questions in TABLE 1 can help you find trouble spots—and hopefully more time for the things that matter most to you.

The next thing you need to know is how you actually spend your time. To find out, record your activities in a time-use diary for one week. Be realistic. Take notes on how much time you spend attending class, studying, working, commuting, meeting personal and family needs, fixing and eating meals, socializing (don’t forget texting, Facebooking, and gaming), exercising, and anything else that occupies your time, including life’s small practical tasks, which can take up plenty of your 24/7. As you record your activities, take notes on how you are feeling at various times of the day. When does your energy slump, and when do you feel most energetic?

Design a Better Schedule

Take a good look at your time-use diary. Where do you think you may be wasting time? Do you spend a lot of time commuting, for example? If so, could you use that time more productively? If you take public transportation, commuting is a great time to read and test yourself for review.

Did you remember to include time for meals, personal care, work schedules, family commitments, and other fixed activities?

How much time do you sleep? In the battle to meet all of life’s daily commitments and interests, we tend to treat sleep as optional. Do your best to manage your life so that you can get enough sleep to feel rested. You will feel better and be healthier, and you will also do better academically and in relationships with your family and friends. (You will read more about this in Chapter 2.)

Are you dedicating enough time for focused study? Take a last look at your notes to see if any other patterns pop out. Now it’s time to create a new and more efficient schedule.

Plan the Term

Before you draw up your new schedule, think ahead. Use your phone’s calendar feature, or buy a portable calendar that covers the entire school term, with a writing space for each day. Using the course outlines provided by your instructors, enter the dates of all exams, term-paper deadlines, and other important assignments. Also be sure to enter your own long-range personal plans (work and family commitments, etc.). Keep your calendar up-to-date, refer to it often, and change it as needed. Through this process, you will develop a regular schedule that will help you achieve success.

Plan Your Week

To pass those exams, meet those deadlines, and keep up with your life outside of class, you will need to convert your long-term goals into a daily schedule. Be realistic—you will be living with this routine for the entire school term. Here are some more things to add to your calendar.

- Enter your class times, work hours, and any other fixed obligations. Be thorough. Allow plenty of time for such things as commuting, meals, and laundry.

- Set up a study schedule for each course. Remember what you learned about yourself in the study habits survey (Table 1) and your time-use diary. Close-Up: More Tips for Effective Scheduling offers some detailed guidance drawn from psychology’s research.

- After you have budgeted time for studying, fill in slots for other obligations, exercise, fun, and relaxation.

Make Every Minute of Your Study Time Count

How do you study from a textbook? Many students simply read and reread in a passive manner. As a result, they remember the wrong things—the catchy stories but not the main points that show up later in test questions. To make things worse, many students take poor notes during class. Here are some tips that will help you get the most from your class and your text.

Take Useful Class Notes

Good notes will boost your understanding and retention. Are yours thorough? Do they form a sensible outline of each lecture? If not, you may need to make some changes.

Keep Each Course’s Notes Separate and Organized

Keeping all your notes for a course in one location will allow you to flip back and forth easily to find answers to questions. Three options are (1) separate notebooks for each course, (2) clearly marked sections in a shared ring binder, or (3) carefully organized folders if you opt to take notes electronically. For the print options, removable pages will allow you to add new information and weed out past mistakes. Choosing notebook pages with lots of space, or using mark-up options in electronic files, will allow you to add comments when you review and revise your notes after class.

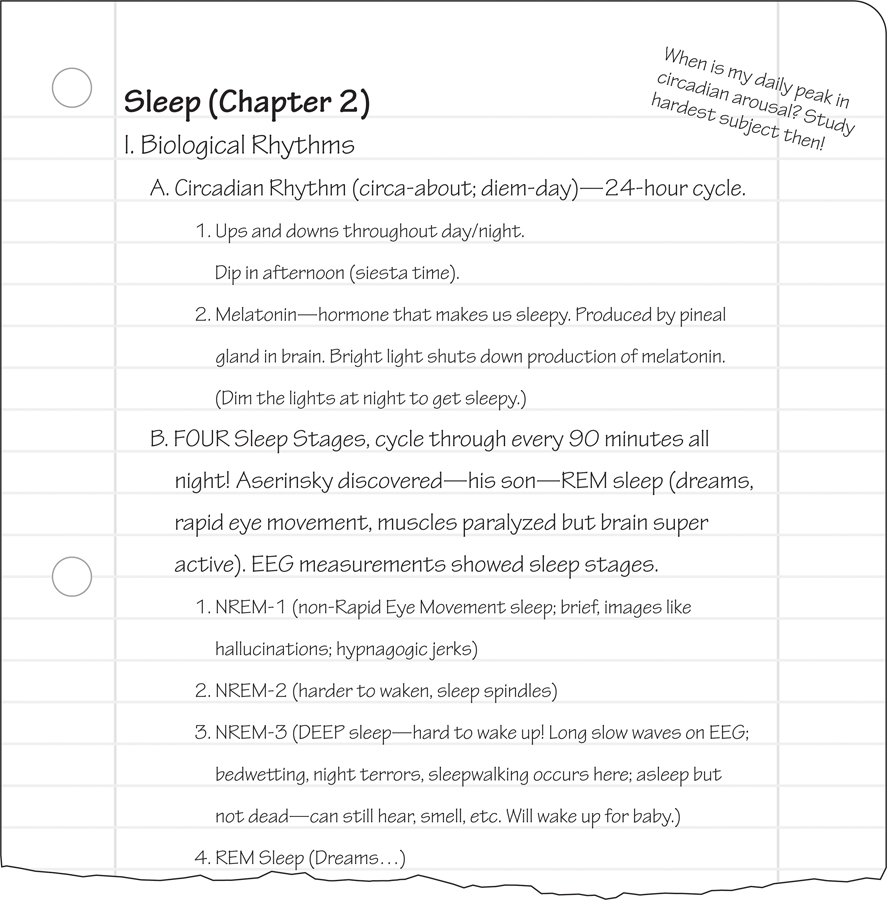

Use an Outline Format

Use roman numerals for major points, letters for supporting arguments, and so on. (See FIGURE 1 for a sample.) In some courses, taking notes will be easy, but some instructors may be less organized, and you will have to work harder to form your outline.

Clean Up Your Notes After Class

Try to reorganize your notes soon after class. Expand or clarify your comments and clean up any hard-to-read scribbles while the material is fresh in your mind. Write important questions in the margin, or by using an electronic markup feature, next to notes that answer them. (For example: “What are the sleep stages?”) This will help you when you review your notes before a test.

CLOSE-UP: More Tips for Effective Scheduling

CLOSE-UP

There are a few other things you will want to keep in mind when you set up your schedule.Spaced study is more effective than massed study. If you need 3 hours to study one subject, for example, it’s best to divide that into shorter periods spaced over several days.

Alternate subjects, but avoid interference. Alternating the subjects you study in any given session will keep you fresh and will, surprisingly, increase your ability to remember what you’re learning in each different area. Studying similar topics back-to-back, however, such as two different foreign languages, could lead to interference in your learning. (You will hear more about this in Chapter 7.)

Determine the amount of study time you need to do well in each course. The time you need depends on the difficulty of your courses and the effectiveness of your study methods. Ideally, you would spend at least 1 to 2 hours studying for each hour spent in class. Increase your study time slowly by setting weekly goals that will gradually bring you up to the desired level.

Create a schedule that makes sense. Tailor your schedule to meet the demands of each course. For the course that emphasizes lecture notes, plan a daily review of your notes soon after each class. If you are evaluated for class participation (for example, in a language course), allow time for a review just before the class meets. Schedule study time for your most difficult (or least motivating) courses during hours when you are the most alert and distractions are fewest.

Schedule open study time. Life can be unpredictable. Emergencies and new obligations can throw off your schedule. Or you may simply need some extra time for a project or for review in one of your courses. Try to allow for some flexibility in your schedule each week.

Following these guidelines will help you find a schedule that works for you!

Create a Study Space That Helps You Learn

It’s easier to study effectively if your work area is well designed.

Organize Your Space

Work at a desk or table, not on your bed or a comfy chair that will tempt you to nap.

Minimize Distractions

Turn the TV off, turn off your phone, and close Facebook and other distracting windows on your computer. If you must listen to music to mask outside noise, play soft instrumentals, not vocal selections that will draw your mind to the lyrics.

Ask Others to Honor Your Quiet Time

Tell roommates, family, and friends about your new schedule. Try to find a study place where you are least likely to be disturbed.

Set Specific, Realistic Daily Goals

The simple note “7–8 P.M.: Study Psychology” is too broad to be useful. Instead, break your studying into manageable tasks. For example, you will want to subdivide large reading assignments. If you aren’t used to studying for long periods, start with relatively short periods of concentrated study, with breaks in between. In this text, for example, you might decide to read one major section before each break. Limit your breaks to 5 or 10 minutes to stretch or move around a bit.

Your attention span is a good indicator of whether you are pacing yourself successfully. At this early stage, it’s important to remember that you’re in training. If your attention begins to wander, get up immediately and take a short break. It is better to study effectively for 15 minutes and then take a break than to fritter away 45 minutes out of your study hour. As your endurance develops, you can increase the length of study periods.

Use SQ3R to Help You Master This Text

David Myers and Nathan DeWall organized this text by using a system called SQ3R (Survey, Question, Read, Retrieve, Review). Using SQ3R can help you to understand what you read, and to retain that information longer.

Applying SQ3R may feel at first as though it’s taking more time and effort to “read” a chapter, but with practice, these steps will become automatic.

Survey

Before you read a chapter, survey its key parts. Scan the chapter outline. Note that main sections have numbered Learning Objective Questions to help you focus. Pay attention to headings, which indicate important subtopics, and to words set in bold type.

Surveying gives you the big picture of a chapter’s content and organization. Understanding the chapter’s logical sections will help you break your work into manageable pieces in your study sessions.

You will hear more about SQ3R in Chapter 1.

Question

As you survey, don’t limit yourself to the numbered Learning Objective Questions that appear throughout the chapter. Jotting down additional questions of your own will cause you to look at the material in a new way. (You might, for example, scan this section’s headings and ask “What does ‘SQ3R’ mean?”) Information becomes easier to remember when you make it personally meaningful. Trying to answer your questions while reading will keep you in an active learning mode.

Read

As you read, keep your questions in mind and actively search for the answers. If you come to material that seems to answer an important question that you haven’t jotted down, stop and write down that new question.

Be sure to read everything. Don’t skip photo or art captions, graphs, boxes, tables, or quotes. An idea that seems vague when you read about it may become clear when you see it in a graph or table. Keep in mind that instructors sometimes base their test questions on figures and tables.

Retrieve

When you have found the answer to one of your questions, close your eyes and mentally recite the question and its answer. Then write the answer next to the question in your own words. Trying to explain something in your own words will help you figure out where there are gaps in your understanding. These kinds of opportunities to practice retrieving develop the skills you will need when you are taking exams. If you study without ever putting your book and notes aside, you may develop false confidence about what you know. With the material available, you may be able to recognize the correct answer to your questions. But will you be able to recall it later, when you take an exam without having your mental props in sight?

Test your understanding as often as you can. Testing yourself is part of successful learning, because the act of testing forces your brain to work at remembering, thus establishing the memory more permanently (so you can find it later for the exam!). Use the self-testing opportunities throughout each chapter, including the periodic Retrieve + Remember items. Also take advantage of the self-testing that is available through LaunchPad (www.worthpublishers.com/launchpad/pel3e).

Review

After working your way through the chapter, read over your questions and your written answers. Take an extra few minutes to create a brief written summary covering all of your questions and answers. At the end of the chapter, you should take advantage of three important opportunities for self-testing and review—a list of the chapter’s Learning Objective Questions for you to try answering before checking your answers, a list of the chapter’s key terms for you to try to define before checking the referenced page, and a final self-test that covers all of the key chapter concepts.

Don’t Forget About Rewards!

If you have trouble studying regularly, giving yourself a reward may help. What kind of reward works best? That depends on what you enjoy. You might start by making a list of 5 or 10 things that put a smile on your face. Spending time with a loved one, taking a walk or going for a bike ride, relaxing with a magazine or novel, or watching a favorite show can provide immediate rewards for achieving short-term study goals.

To motivate yourself when you’re having trouble sticking to your schedule, allow yourself an immediate reward for completing a specific task. If running makes you smile, change your shoes, grab a friend, and head out the door! You deserve a reward for a job well done.

Do You Need to Revise Your New Schedule?

What if you’ve lived with your schedule for a few weeks, but you aren’t making progress toward your academic and personal goals? What if your studying hasn’t paid off in better grades? Don’t despair and abandon your program, but do take a little time to figure out what’s gone wrong.

Are You Doing Well in Some Courses But Not in Others?

Perhaps you need to shift your priorities a bit. You may need to allow more study time for chemistry, for example, and less time for some other course.

Have You Received a Poor Grade on a Test?

Did your grade fail to reflect the effort you spent preparing for the test? This can happen to even the hardest-working student, often on a first test with a new instructor. This common experience can be upsetting. “What do I have to do to get an A?” “The test was unfair!” “I studied the wrong material!”

Try to figure out what went wrong. Analyze the questions you missed, dividing them into two categories: class-based questions and text-based questions. How many questions did you miss in each category? If you find far more errors in one category than in the other, you’ll have some clues to help you revise your schedule. Depending on the pattern you’ve found, you can add extra study time to review of class notes, or to studying the text.

Are You Trying to Study Regularly for the First Time and Feeling Overwhelmed?

Perhaps you’ve set your initial goals too high. Remember, the point of time management is to identify a regular schedule that will help you achieve success. Like any skill, time management takes practice. Accept your limitations and revise your schedule to work slowly up to where you know you need to be—perhaps adding 15 minutes of study time per day.

I hope that these suggestions help make you more successful academically, and that they enhance the quality of your life in general. Having the necessary skills makes any job a lot easier and more pleasant. Let me repeat my warning not to attempt to make too drastic a change in your lifestyle immediately. Good habits require time and self-discipline to develop. Once established, they can last a lifetime.

nagement: Or, How to Be a Great Student and Still Have a Life

Time Management: Or, How to Be a Great Student and Still Have a Life

How Are You Using Your Time Now?

- Identify your areas of weakness.

- Keep a time-use diary.

- Record the time you actually spend on activities.

- Record your energy levels to find your most productive times.

Design a Better Schedule

- Decide on your goals for the term and for each week.

- Enter class times, work times, social times (for family and friends), and time needed for other obligations and for practical activities.

- Tailor study times to avoid interference and to meet each course’s needs.

Make Every Minute of Your Study Time Count

- Take careful class notes (in outline form) that will help you recall and rehearse material covered in lectures.

- Try to eliminate distractions to your study time, and ask friends and family to help you focus on your work.

- Set specific, realistic daily goals to help you focus on each day’s tasks.

- Use the SQ3R system (survey, question, read, retrieve, review) to master material covered in your text.

- When you achieve your daily goals, reward yourself with something that you value.

Do You Need to Revise Your New Schedule?

- Allocate extra study time for courses that are more difficult, and a little less time for courses that are easy for you.

- Study your test results to help determine a more effective balance in your schedule.

- Make sure your schedule is not too ambitious. Gradually establish a schedule that will be effective for the long term.