10.3 Coping With Stress

LOQ 10-

coping reducing stress using emotional, cognitive, or behavioral methods.

Stressors are unavoidable. That’s the reality we live with. One way we can develop our strengths and protect our health is to learn better ways to cope with our stress.

problem-

We need to find new ways to feel, think, and act when we are dealing with stressors. We address some stressors directly, with problem-

emotion-

We turn to emotion-

Emotion-

Our success in coping depends on several factors. Let’s look at four of them: personal control, an optimistic outlook, social support, and finding meaning in life’s ups and downs.

Retrieve + Remember

Question 10.4

•To cope with stress, we tend to use _______-focused (emotion/problem) strategies when we feel in control of our world. When we believe we cannot change a situation, we may try to relieve stress with _______-focused (emotion/problem) strategies.

ANSWERS: problem; emotion

Personal Control, Health, and Well-Being

LOQ 10-

personal control our sense of controlling our environment rather than feeling helpless.

Personal control refers to how much we perceive having control over our environment. Psychologists study the effect of personal control (or any personality factor) in two ways:

They correlate people’s feelings of control with their behaviors and achievements.

They experiment, by raising or lowering people’s sense of control and noting the effects.

learned helplessness the hopelessness and passive resignation an animal or person learns when unable to avoid repeated aversive events.

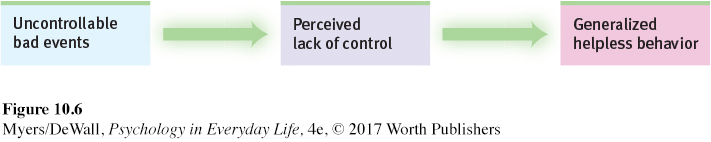

At times, we all feel helpless, hopeless, and depressed after experiencing a series of bad events beyond our control. For some animals and people, a series of uncontrollable events creates a state of learned helplessness, with feelings of passive resignation (FIGURE 10.6). In one series of experiments, dogs were strapped in a harness and given repeated shocks, with no opportunity to avoid them (Seligman & Maier, 1967). When later placed in another situation where they could escape the punishment by simply leaping a hurdle, the dogs cowered as if without hope. Other dogs that had been able to escape the first shocks reacted differently. They had learned they were in control, and in the new situation they easily escaped the shocks (Seligman & Maier, 1967). In other experiments, people have shown similar patterns of learned helplessness (Abramson et al., 1978, 1989; Seligman, 1975).

Learned helplessness is a dramatic form of loss of control. But we’ve all felt a loss of control at times. Our health can suffer as our level of stress hormones (such as cortisol) rise, our blood pressure increases, and our immune responses weaken (Rodin, 1986; Sapolsky, 2005). One study found these effects among nurses, who reported their workload and their level of personal control on the job. The greater their workload, the higher their cortisol level and blood pressure—

Proposals to improve health and morale by increasing control have included (Humphrey et al., 2007; Ruback et al., 1986; Warburton et al., 2006):

Allowing prisoners to move chairs and control room lights and the TV.

Having workers participate in decision making. Simply allowing people to personalize their workspace has been linked with higher (55 percent) engagement with their work (Krueger & Killham, 2006).

Offering nursing home patients choices about their environment. In one famous study, 93 percent of nursing home patients who were encouraged to exert more control became more alert, active, and happy (Rodin, 1986).

“Perceived control is basic to human functioning,” concluded researcher Ellen Langer (1983, p. 291). “For the young and old alike,” she suggested, environments should enhance people’s sense of control over their world. No wonder mobile devices and online streaming, which enhance our control of the content and timing of our entertainment, are so popular.

Google has incorporated these principles effectively. Each week, Google employees can spend 20 percent of their working time on projects they find personally interesting. This Innovation Time Off program has increased employees’ personal control over their work environment. It has also paid off: Gmail was developed this way.

The power of personal control also appears at the national level. People thrive when they live in conditions of personal freedom and empowerment. For example, citizens of stable democracies report higher levels of happiness (Inglehart et al., 2008).

So, some freedom and control are better than none. But does ever-

Who Controls Your Life?

Do you believe that your life is out of control? That the world is run by a few powerful people? That getting a good job depends mainly on being in the right place at the right time? Or do you more strongly believe that you control your own fate? That each of us can influence our government’s decisions? That being a success is a matter of hard work?

Hundreds of studies have compared people who differ in their perceptions of control:

external locus of control the perception that chance or outside forces beyond our personal control determine our fate.

Those who have an external locus of control believe that chance or outside forces control their fate.

internal locus of control the perception that we control our own fate.

Those who have an internal locus of control believe they control their own destiny.

Does it matter which view we hold? In study after study comparing people with these two viewpoints, the “internals” have achieved more in school and work, acted more independently, enjoyed better health, and felt less depressed (Lefcourt, 1982; Ng et al., 2006). In one long-

Another way to say that we believe we are in control of our own life is to say we have free will, or that we can control our own willpower. Studies show that people who believe in their freedom learn better, enjoy making decisions, perform better at work, and behave more helpfully (Clark et al., 2014; Feldman et al., 2014a; Stillman et al., 2010).

So we differ in our perceptions of whether we have control over our world. Compared with their parents’ generation, more young Americans now express an external locus of control (Twenge et al., 2004). This shift may help explain an associated increase in rates of depression and other psychological disorders (Twenge et al., 2010).

Coping With Stress by Boosting Self-Control

self-

Google trusted its belief in the power of personal control, and the company and its employees reaped the benefits. Could we reap similar benefits by actively managing our own behavior? One place to start might be increasing our self-

Self-

When you use your self-

Exercising self-

Weakened mental energy after exercising self-

The point to remember: Develop self-

Is the Glass Half Full or Half Empty?

LOQ 10-

optimism the anticipation of positive outcomes. Optimists are people who expect the best and expect their efforts to lead to good things.

pessimism the anticipation of negative outcomes. Pessimists are people who expect the worst and doubt that their goals will be achieved.

Another part of coping with stress is our outlook—

Positive expectations often motivate eventual success.

Optimism, like a feeling of personal control, pays off. Optimists respond to stress with smaller increases in blood pressure, and they recover more quickly from heart bypass surgery. And during the stressful first few weeks of classes, U.S. law school students who were optimistic (“It’s unlikely that I will fail”) enjoyed better moods and stronger immune systems (Segerstrom et al., 1998). When American dating couples wrestle with conflicts, optimists and their partners see each other as engaging constructively. They tend to feel more supported and satisfied with the resolution and with their relationship (Srivastava et al., 2006). Optimism also predicts well-

Is an optimistic outlook related to living a longer life? Possibly. One research team followed 941 Dutch people, aged 65 to 85, for nearly a decade (Giltay et al., 2004, 2007). They split the sample into four groups according to their optimism scores. Only 30 percent of those with the highest optimism died during the study, compared with 57 percent of those with the lowest optimism.

The optimism–

Optimism runs in families, so some people truly are born with a sunny, hopeful outlook. If one identical twin is optimistic, the other often will be as well (Bates, 2015; Mosing et al., 2009). One genetic marker of optimism is a gene that enhances the social-

Positive thinking pays dividends, but so does a dash of realism (Schneider, 2001). Realistic anxiety over possible future failures—

“God grant us the serenity to accept the things we cannot change, courage to change the things we can, and wisdom to know the difference.”

Alcoholics Anonymous Serenity Prayer (attributed to Reinhold Niebuhr)

Excessive optimism can blind us to real risks (Weinstein, 1980, 1982, 1996). Most college students display an unrealistic optimism. They view themselves as less likely than their average classmate to develop drinking problems, drop out of school, or have a heart attack. Many credit-

Social Support

LOQ 10-

Which of these factors has the strongest association with poor health: smoking 15 cigarettes daily, being obese, being inactive, or lacking strong social connections? This is a trick question, because each factor has a roughly similar impact (Cacioppo & Patrick, 2008). That’s right! Social support—

Seven massive international investigations that followed thousands of people over several years reached similar conclusions. Although individualist (individual-

Happy marriages bathe us in social support. One seven-

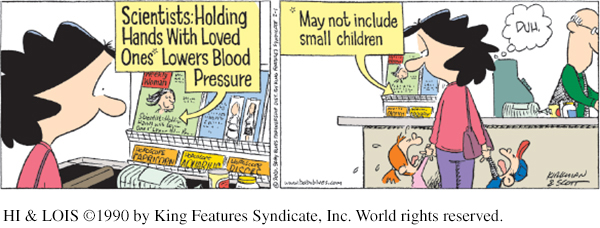

Social support helps us fight illness in at least two ways. First, it calms our cardiovascular system, which lowers blood pressure and stress hormone levels (Baron et al., 2016; Uchino et al., 1996, 1999). To see if social support might calm people’s response to threats, one research team subjected happily married women, while lying in an fMRI machine, to the threat of electric shock to an ankle (Coan et al., 2006). During the experiment, some women held their husband’s hand. Others held a stranger’s hand or no hand at all. While awaiting the occasional shocks, the women’s brains reacted differently. Those who held their husband’s hand had less activity in threat-

Social support helps us cope with stress in a second way. It helps us fight illness by fostering stronger immune functioning. We have seen that stress puts us at risk for disease by stealing disease-

When we are trying to cope with stressors, social ties can tug us toward or away from our goal. Are you trying to exercise more, drink less, quit smoking, or eat better? If so, think about whether your social network can help or hinder you. That social net covers not only the people you know but friends of your friends, and friends of their friends. That’s three degrees of separation between you and the most remote people. This means that people you have never met can influence your thoughts, feelings, and actions without your awareness (Christakis & Fowler, 2009; Kim et al., 2015).

Finding Meaning

Catastrophes and significant life changes can leave us confused and distressed as we try to make sense of what happened. At such times, an important part of coping with stress is finding meaning in life—

Close relationships offer an opportunity for “open heart therapy”—a chance to confide painful feelings and sort things out (Frattaroli, 2006). Talking about things that push our buttons may arouse us in the short term. But in the long term, it calms us by reducing our physical stress responses (Lieberman et al., 2007; Mendolia & Kleck, 1993; Niles et al., 2015). After we gain distance from a stressful event, talking or writing about the experience helps us make sense of it and find meaning in it (Esterling et al., 1999). In one study, 33 Holocaust survivors spent two hours recalling their experiences, many in intimate detail never before disclosed (Pennebaker et al., 1989). In the weeks following, most watched a video of their recollections and showed it to family and friends. Those who were most self-