10.4 Managing Stress Effects

Having a sense of control, nurturing an optimistic outlook, building our social support, and finding meaning can help us experience less stress and thus improve our health. What do we do when we cannot avoid stress? At such times, we need to manage our stress. Aerobic exercise, relaxation, meditation, and active spiritual engagement may help us gather inner strength and lessen stress effects.

Aerobic Exercise

LOQ 10-

aerobic exercise sustained activity that increases heart and lung fitness; may also reduce depression and anxiety.

It’s hard to find a medicine that works for most people most of the time. But aerobic exercise—sustained activity that increases heart and lung fitness—

Throughout this book, we have revisited one of psychology’s basic themes: Heredity and environment interact. Physical activity can weaken the influence of genetic risk factors for obesity. In one analysis of 45 studies, that risk fell by 27 percent (Kilpeläinen et al., 2012). Exercise also helps fight heart disease. It strengthens your heart, increases bloodflow, keeps blood vessels open, lowers overall blood pressure, and reduces the hormone and blood pressure reaction to stress (Ford, 2002; Manson, 2002). Compared with inactive adults, people who exercise suffer half as many heart attacks (Powell et al., 1987; Visich & Fletcher, 2009). Exercise makes the muscles hungry for the fats that, if not used by the muscles, contribute to clogged arteries (Barinaga, 1997).

Many studies suggest that aerobic exercise reduces stress, depression, and anxiety. People who exercise at least 30 minutes, three times a week manage stressful situations better, have more self-

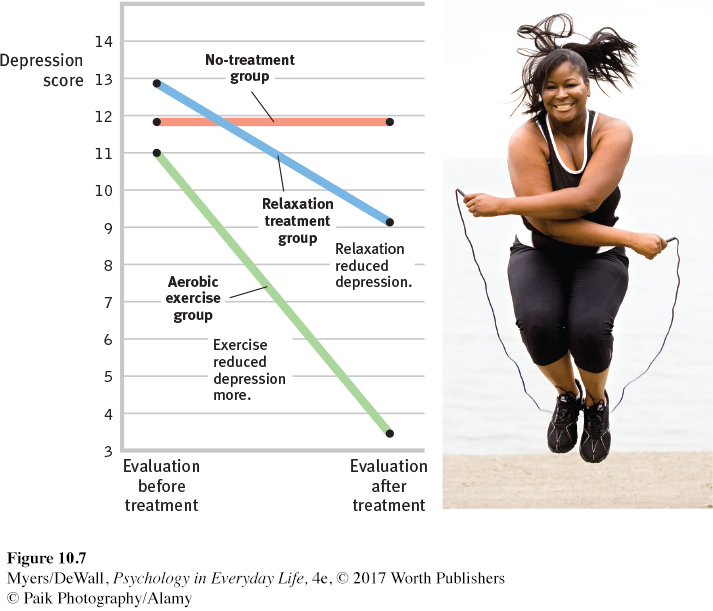

To sort out cause and effect, researchers experiment. They randomly assign people either to an aerobic exercise group or to a control group. Next, they measure whether aerobic exercise (compared with a control activity that doesn’t involve exercise) produces a change in stress, depression, anxiety, or some other health-

Group 1 completed an aerobic exercise program.

Group 2 completed a relaxation program.

Group 3 functioned as a pure control group and did not complete any special activity.

As FIGURE 10.7 shows, 10 weeks later the women in the aerobic exercise program reported the greatest decrease in depression. Many of them had, quite literally, run away from their troubles.

Another experiment randomly assigned depressed people to an exercise group, an antidepressant group, or a placebo pill group. Again, exercise diminished depression levels. And it did so as effectively as antidepressants, with longer-

See LaunchPad’s Video: Random Assignment for a helpful tutorial animation about this important part of effective research design.

See LaunchPad’s Video: Random Assignment for a helpful tutorial animation about this important part of effective research design.

More than 150 other studies have confirmed that exercise reduces depression and anxiety. What is more, toned muscles filter out depression-

Relaxation and Meditation

LOQ 10-

Sit with your back straight, getting as comfortable as you can. Breathe a deep, single breath of air through your nose. Now exhale that air through your mouth as slowly as you can. As you exhale, repeat a focus word, phrase, or prayer—

Why Relaxation Is Good

Like aerobic exercise, relaxation can improve our well-

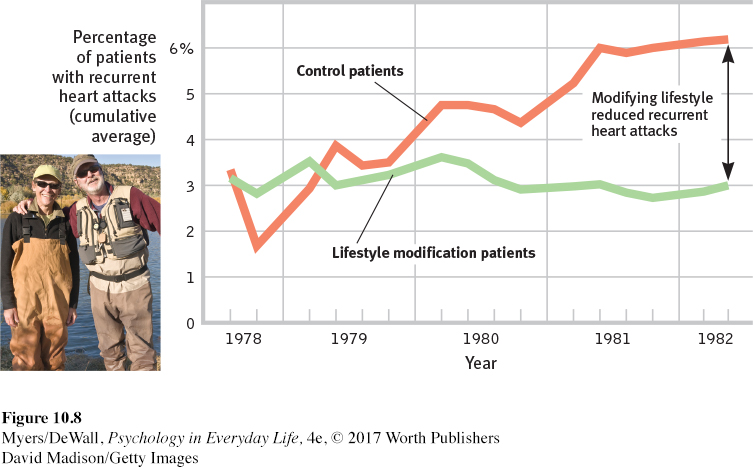

Researchers have even used relaxation to help Type A heart attack survivors reduce their risk of future attacks (Friedman & Ulmer, 1984). They randomly assigned hundreds of these middle-

Time may heal all wounds, but relaxation can help speed that process. In one study, surgery patients were randomly assigned to two groups. Both groups received standard treatment, but the second group also experienced a 45-

Learning to Reflect and Accept

mindfulness meditation a reflective practice in which people attend to current experiences in a nonjudgmental and accepting manner.

Meditation is a modern practice with a long history in a variety of world religions. Meditation was originally used to reduce suffering and improve awareness, insight, and compassion. Numerous studies have confirmed the psychological benefits of meditation (Goyal et al., 2014; Rosenberg et al., 2015; Sedlmeier et al., 2012), including mindfulness meditation, which has today found a new home in stress management programs. If you were taught this practice, you would relax and silently attend to your inner state, without judging it (Kabat-

Practicing mindfulness may improve many health measures. In one study of 1140 people, some received mindfulness-

So, what’s going on in the brain as we practice mindfulness? Correlational and experimental studies offer three explanations for how mindfulness helps us make positive changes:

It strengthens connections among regions in our brain. The affected regions are those associated with focusing our attention, processing what we see and hear, and being reflective and aware (Berkovich-

Ohana et al., 2014; Ives- Deliperi et al., 2011; Kilpatrick et al., 2011). It activates brain regions associated with more reflective awareness (Davidson et al., 2003; Way et al., 2010). When labeling emotions, mindful people show less activation in the amygdala, a brain region associated with fear, and more activation in the prefrontal cortex, which aids emotion regulation (Creswell et al., 2007).

It calms brain activation in emotional situations. This lower activation was clear in one study in which participants watched two movies—

one sad, one neutral. Those in the control group, who were not trained in mindfulness, showed strong differences in brain activation when watching the two movies. Those who had received mindfulness training showed little change in brain response to the two movies (Farb et al., 2010). Emotionally unpleasant images also trigger weaker electrical brain responses in mindful people than in their less mindful counterparts (Brown et al., 2013). A mindful brain is strong, reflective, and calm.

Faith Communities and Health

LOQ 10-

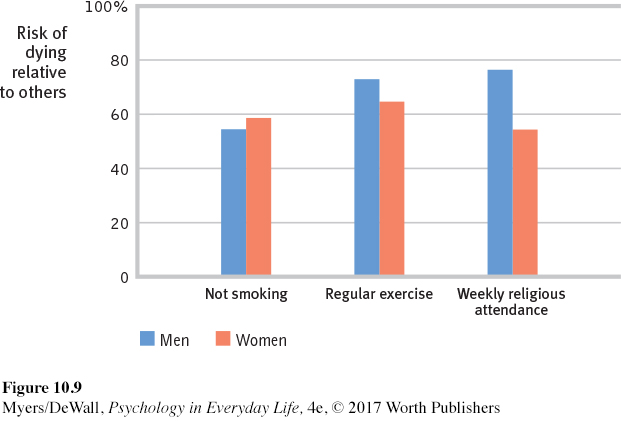

A wealth of studies has revealed another curious correlation, called the faith factor (Koenig et al., 2012). Religiously active people tend to live longer than those who are not religiously active. In one 16-

How should we interpret such findings? Remember that correlation does not mean causation. What other factors might explain these protective effects? Here’s one possibility: Women are more religiously active than men, and women outlive men. Does religious involvement reflect this gender-

Does this mean that nonattenders who start attending services and change nothing else will live longer? Again, the answer is No. But we can say that religious involvement predicts health and longevity, just as nonsmoking and exercise do. Religiously active people have demonstrated healthier immune functioning, fewer hospital admissions, and, for people with AIDS, fewer stress hormones and longer survival (Ironson et al., 2002; Koenig & Larson, 1998; Lutgendorf et al., 2004).

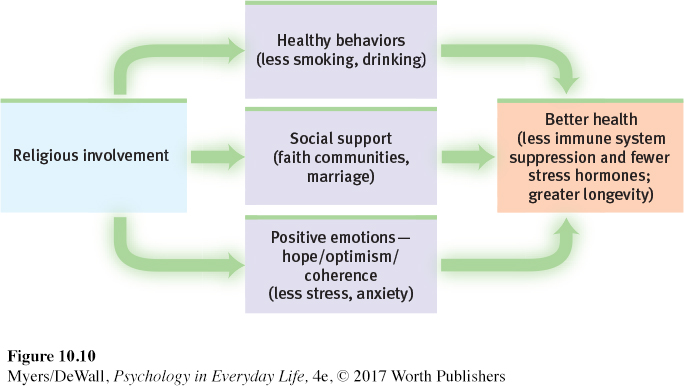

Can you imagine why religiously active people might be healthier and live longer than others? Here are three factors that help explain the correlation:

Healthy lifestyles Religiously active people have healthier lifestyles. For example, they smoke and drink less (Islam & Johnson, 2003; Koenig &Vaillant, 2009; Koopmans et al., 1999). In one Gallup survey of 550,000 Americans, 15 percent of the very religious were smokers, compared with 28 percent of nonreligious people (Newport et al., 2010). But healthy lifestyles are not the complete answer. In studies that have controlled for unhealthy behaviors, such as inactivity and smoking, about 75 percent of the life-

span difference remained (Musick et al., 1999). Social support Those who belong to a faith community have access to a support network. When misfortune strikes, religiously active people can turn to each other. Moreover, religions encourage marriage, another predictor of health and longevity. In the Israeli religious settlements, for example, divorce has been almost nonexistent. But even after controlling for social support, gender, unhealthy behaviors, and preexisting health problems, much of the original religious engagement correlation remains (Chida et al., 2009; George et al., 2000; Kim-

Yeary et al., 2012; Powell et al., 2003). Positive emotions Researchers speculate that a third set of influences helps protect religiously active people from stress and enhance their well-

being (FIGURE 10.10). Religiously active people have a stable worldview, a sense of hope for the long- term future, and feelings of ultimate acceptance. They may also benefit from the relaxed meditation of prayer or other religious observances. Taken together, these positive emotions, expectations, and practices may have a protective effect on well- being.  Figure 10.11: FIGURE 10.10 Possible explanations for the correlation between religious involvement and health/longevity

Figure 10.11: FIGURE 10.10 Possible explanations for the correlation between religious involvement and health/longevity

* * *

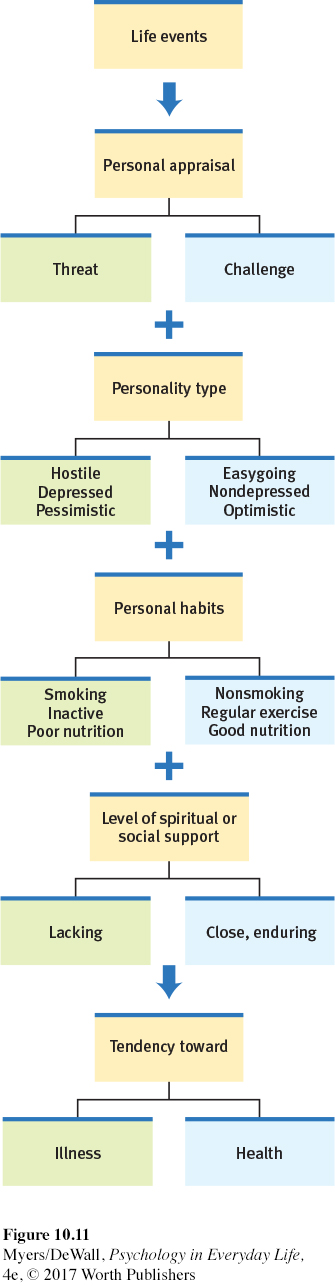

Let’s summarize what we’ve learned so far: Sustained emotional reactions to stressful events can be damaging. However, some qualities and influences can help us cope with life’s challenges by making us emotionally and physically stronger. These include a sense of control, an optimistic outlook, relaxation, healthy habits, social support, a sense of meaning, and spirituality (FIGURE 10.11).

In the remainder of this chapter, we’ll take a closer look at our pursuit of happiness and how it relates to our human flourishing.

Retrieve + Remember

Question 10.5

•What are some of the tactics that help people manage the stress they cannot avoid?

ANSWER: aerobic exercise, relaxation procedures, mindfulness meditation, and religious engagement