11.2 Social Thinking

When we try to explain people’s actions, our search for answers often leaves us with two choices. We can attribute behavior to a person’s stable, enduring traits. Or we can attribute behavior to the situation (Heider, 1958). Our explanations, or attributions, affect our feelings and actions.

The Fundamental Attribution Error

LOQ 11-

fundamental attribution error the tendency, when analyzing others’ behavior, to overestimate the influence of personal traits and underestimate the effects of the situation.

In class, we notice that Juliette seldom talks. Over coffee, Jack talks nonstop. That must be the sort of people they are, we decide. Juliette must be shy and Jack outgoing. Are they? Perhaps. People do have enduring personality traits. But often our explanations are wrong. We fall prey to the fundamental attribution error: We give too much weight to the influence of personality and too little to the influence of situations. In class, Jack may be as quiet as Juliette. Catch Juliette at a party and you may hardly recognize your quiet classmate.

For a quick interactive tutorial, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: Making Attributions.

For a quick interactive tutorial, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: Making Attributions.

Researchers demonstrated this tendency in an experiment with college students (Napolitan & Goethals, 1979). They had students talk, one at a time, with a young woman who acted either cold and critical or warm and friendly. Before the talks, researchers told half the students that the woman’s behavior would be normal and natural. They told the other half the truth—

Did hearing the truth affect students’ impressions of the woman? Not at all! If the woman acted friendly, both groups decided she really was a warm person. If she acted unfriendly, both decided she really was a cold person. In other words, they attributed her behavior to her personal traits, even when they were told that her behavior was part of the experimental situation.

The fundamental attribution error appears more often in some cultures than in others. Individualist Westerners more often attribute behavior to people’s personal traits. People in East Asian cultures are more sensitive to the power of situations (Masuda & Kitayama, 2004; Riemer et al., 2014). This difference appeared in experiments in which people were asked to view scenes, such as a big fish swimming. Americans focused more on the individual fish; Japanese people focused on the whole scene (Chua et al., 2005; Nisbett, 2003).

To see how easily we make the fundamental attribution error, answer this question: Is your psychology instructor shy or outgoing?

If you’re tempted to answer “outgoing,” remember that you know your instructor from one situation—

When we explain our own behavior, we are sensitive to how behavior changes with the situation (Idson & Mischel, 2001). We also are sensitive to the power of the situation when we explain the behavior of people we have seen in many different contexts. So, when are we most likely to commit the fundamental attribution error? The odds are highest when a stranger acts badly. Having never seen this person in other situations, we assume he must be a bad person. But outside the stadium, that red-

Could we broaden our thinking by taking another person’s view? To test this idea, researchers have reversed the perspectives of actor and observer. They filmed two people interacting, with a camera behind each person. Then they showed each person a replay of their interaction—

Reflecting on our past selves of 5 or 10 years ago also switches our perspective. Our present self adopts the observer’s perspective and attributes our past behavior mostly to our traits (Pronin & Ross, 2006). In another 5 or 10 years, your current self may seem like another person.

The way we explain others’ actions, attributing them to the person or the situation, can have important real-

Finally, consider the social effects of attribution. How should we explain poverty or unemployment? In Britain, India, Australia, and the United States, political conservatives have tended to attribute responsibility to the personal traits of the poor and unemployed (Furnham, 1982; Pandey et al., 1982; Wagstaff, 1982; Zucker & Weiner, 1993). “People generally get what they deserve. Anybody who tries hard can still get ahead.” In experiments, after reflecting on the power of choice—

The point to remember: Our attributions—

Attitudes and Actions

LOQ 11-

attitude feelings, often based on our beliefs, that predispose us to respond in a particular way to objects, people, and events.

Attitudes are feelings, often based on our beliefs, that can influence how we respond to particular objects, people, and events. If we believe someone is mean, we may feel dislike for the person and act unfriendly. That helps explain a noteworthy finding. If people in a country intensely dislike the leaders of another country, their country is more likely to produce terrorist acts against that country (Krueger & Malecková, 2009). Hateful attitudes breed violent behavior.

Attitudes Affect Actions

Knowing that public attitudes affect public policies, people on both sides of any debate aim to persuade. Persuasion efforts generally take two forms:

peripheral route persuasion occurs when people are influenced by unimportant cues, such as a speaker’s attractiveness.

Peripheral route persuasion uses unimportant cues to trigger speedy, emotion-

based judgments. Beautiful and famous people can affect people’s attitudes about everything from perfume to climate change. central route persuasion occurs when interested people focus on the arguments and respond with favorable thoughts.

Central route persuasion offers evidence and arguments in hopes of motivating careful thinking. This form works well for people who are naturally analytical or involved in an issue.

Attitudes affect our behavior, but other factors, including the situation, also influence behavior. For example, in roll-

When are attitudes most likely to affect behavior? Under these conditions (Glasman & Albarracin, 2006):

External influences are minimal.

The attitude is stable.

The attitude is specific to the behavior.

The attitude is easily recalled.

One experiment used vivid, easily recalled information to persuade people that sustained tanning put them at risk for future skin cancer. One month later, 72 percent of the participants, and only 16 percent of those in a waitlist control group, had lighter skin (McClendon & Prentice-

Actions Affect Attitudes

People also come to believe in what they have stood up for. Many streams of evidence confirm that attitudes follow behavior (FIGURE 11.1).

FOOT-

foot-

How did the Chinese captors achieve these amazing results? A key ingredient was their effective use of the foot-

In dozens of experiments, researchers have coaxed people into acting against their attitudes or violating their moral standards, with the same result. Doing becomes believing. After giving in to a request to harm an innocent victim—

Fortunately, the principle that attitudes follow behavior works as well for good deeds as for bad. After U.S. schools were desegregated and the 1964 Civil Rights Act was passed, White Americans expressed lower levels of racial prejudice. And as Americans in different regions came to act more alike—

role a set of expectations about a social position, defining how those in the position ought to behave.

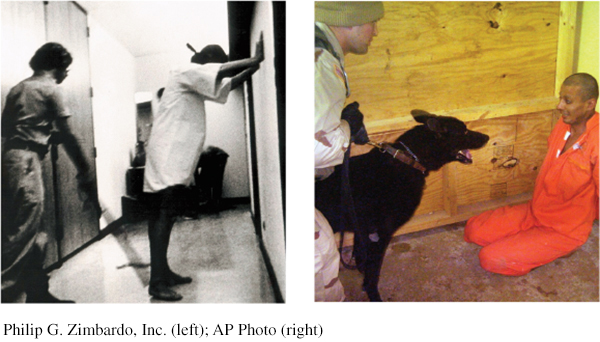

ROLE-

Role-

Although critics question the reliability of Zimbardo’s results, there is evidence that role-

To view Philip Zimbardo’s 14-

To view Philip Zimbardo’s 14-

cognitive dissonance theory the theory that we act to reduce the discomfort (dissonance) we feel when two of our thoughts (cognitions) clash. For example, when we become aware that our attitudes and our actions don’t match, we may change our attitudes so that we feel more comfortable.

COGNITIVE DISSONANCE: RELIEF FROM TENSION We have seen that actions can affect attitudes, sometimes turning prisoners of war into collaborators, doubters into believers, and guards into abusers. But why? One explanation is that when we become aware of a mismatch between our attitudes and actions, we experience mental discomfort, or cognitive dissonance. Indeed, the brain regions that become active when people experience cognitive conflict and negative arousal also become active when people experience cognitive dissonance (de Vries et al., 2015; Kitayama et al., 2013). To relieve this tension, according to Leon Festinger’s cognitive dissonance theory, we often bring our attitudes into line with our actions.

Dozens of experiments have tested this attitudes-

To check your understanding of cognitive dissonance, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: Cognitive Dissonance.

To check your understanding of cognitive dissonance, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: Cognitive Dissonance.

The attitudes-

The point to remember: Cruel acts shape the self. But so do acts of good will. Act as though you like someone, and you soon may. Changing our behavior can change how we think about others and how we feel about ourselves.

Retrieve + Remember

Question 11.1

•Driving to school one snowy day, Marco narrowly misses a car that slides through a red light. “Slow down! What a terrible driver,” he thinks to himself. Moments later, Marco himself slips through an intersection and yelps, “Wow! These roads are awful. The city plows need to get out here.” What social psychology principle has Marco just demonstrated? Explain.

ANSWER: By attributing the other person’s behavior to personal traits (“what a terrible driver”) and his own to the situation (“these roads are awful”), Marco has exhibited the fundamental attribution error.

Question 11.2

•How do our attitudes and our actions affect each other?

ANSWER: Our attitudes often influence our actions, as we behave in ways consistent with our beliefs. However, our actions also influence our attitudes; we come to believe in what we have done.

Question 11.3

•When people act in a way that is not in keeping with their attitudes, and then change their attitudes to match those actions, __________ __________ theory attempts to explain why.

ANSWER: cognitive dissonance