13.3 Substance Use Disorders and Addictive Behaviors

LOQ 13-

psychoactive drug a chemical substance that alters perceptions and mood.

substance use disorder disorder characterized by continued substance craving and use despite significant life disruption and/or physical risk.

Do you rely on caffeine pick-

|

According to the American Psychiatric Association, a person may be diagnosed with a substance use disorder when drug use continues despite significant life disruption. Resulting brain changes may persist after quitting use of the substance (thus leading to strong cravings when exposed to people and situations that trigger memories of drug use). The severity of substance use disorder varies from mild (two to three of the indicators listed below) to moderate (four to five indicators) to severe (six or more indicators). (Source: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.) |

|

Diminished Control

|

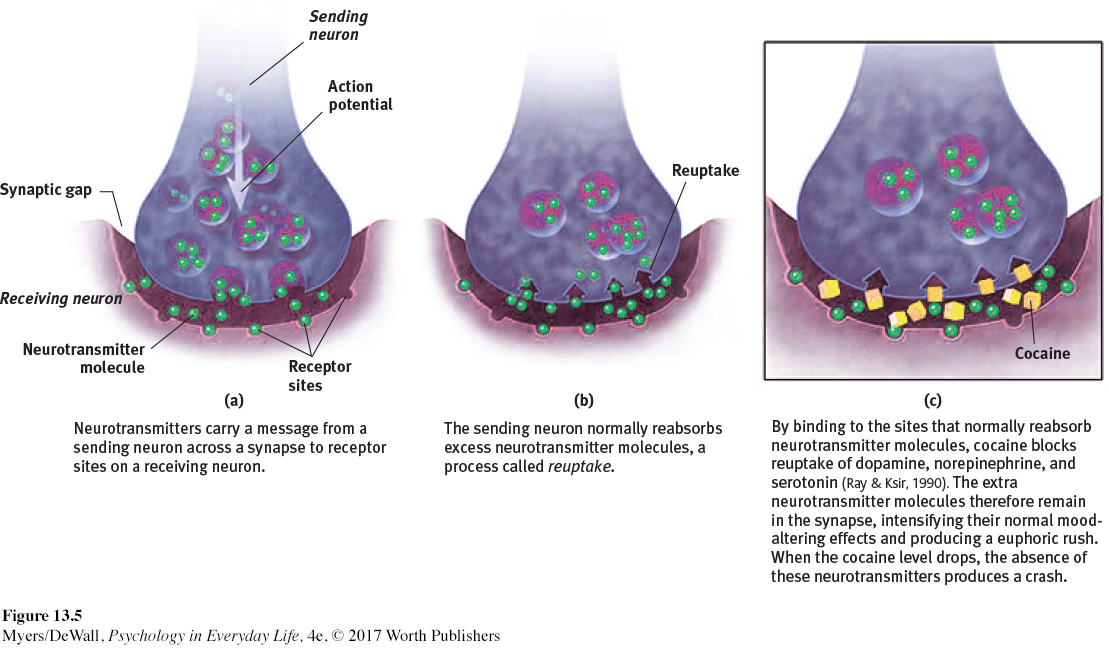

The three major categories of psychoactive drugs are depressants, stimulants, and hallucinogens. All do their work at the brain’s synapses. They stimulate, inhibit, or mimic the activity of the brain’s own chemical messengers, the neurotransmitters. But our reaction to psychoactive drugs depends on more than their biological effects. Psychological influences, including a user’s expectations, and cultural traditions also play a role (Scott-

Tolerance and Addictive Behaviors

tolerance a dwindling effect with regular use of the same dose of a drug, requiring the user to take larger and larger doses before experiencing the drug’s effect.

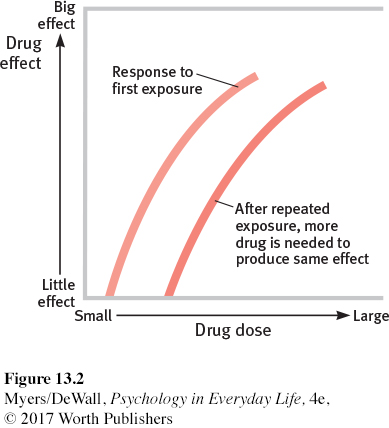

Why might a person who rarely drinks alcohol get buzzed on one can of beer, while a long-

withdrawal the discomfort and distress that follow ending the use of an addictive drug or behavior.

Ever-

Sometimes even behaviors become compulsive and dysfunctional, much like abusive drug-

Retrieve + Remember

Question 13.11

•What is the process that leads to drug tolerance?

ANSWER: With repeated exposure to a psychoactive drug, the user’s brain chemistry adapts and the drug’s effect lessens. Thus, it takes bigger doses to get the desired effect.

Depressants

LOQ 13-

depressants drugs (such as alcohol, barbiturates, and opiates) that reduce (depress) neural activity and slow body functions.

Depressants are drugs such as alcohol, barbiturates (tranquilizers), and opiates that calm (depress) neural activity and slow body functions.

ALCOHOL True or false? Alcohol is a depressant in large amounts but is a stimulant in small amounts. False. In any amount, alcohol is a depressant—

Slowed neural functions. Low doses of alcohol may, indeed, enliven a drinker, but they do so by acting as a disinhibitor. Alcohol slows activity in a part of the brain that controls judgment and inhibitions. As a result, the urges we would feel if sober are the ones we will more likely act upon when intoxicated. Alcohol is an equal-

Even the belief that we have consumed alcohol can influence our judgment. In one classic experiment (supposedly a study on “alcohol and sexual stimulation”), researchers gave college male volunteers either an alcoholic or a nonalcoholic drink (Abrams & Wilson, 1983). (Both drinks had a strong taste that masked any alcohol.) After watching an erotic movie clip, the men who thought they had consumed alcohol were more likely to report having strong sexual fantasies and feeling guilt free—

Alcohol does more than lessen our normal inhibitions, however. It produces a sort of short-

The point to remember: Alcohol’s effect lies partly in that powerful sex organ, the mind. Expectations influence behavior.

Memory disruption. Sometimes, people drink to forget their troubles—

Heavy drinking can have long-

Slowed body functions. Alcohol slows sympathetic nervous system activity. In low doses, it relaxes the drinker. In larger doses, it causes reactions to slow, speech to slur, and skilled performance to decline.

Paired with lack of sleep, alcohol is a potent sedative. Add these physical effects to lowered inhibitions, and the result can be deadly. Worldwide, several hundred thousand lives are lost each year in alcohol-

Alcohol can be life threatening when heavy drinking follows an earlier period of moderate drinking, which suppresses the vomiting response. People may poison themselves with an overdose their body would normally throw up.

alcohol use disorder (popularly known as alcoholism) alcohol use marked by tolerance, withdrawal, and a drive to continue problematic use.

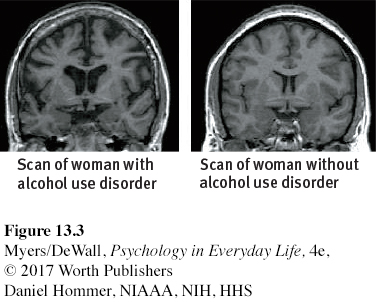

Alcohol use disorder. Alcoholism is the popular name for alcohol use disorder. Its symptoms are tolerance, withdrawal, and a drive to continue using alcohol despite significant problems associated with that use. Girls and young women are especially vulnerable because they have less of a stomach enzyme that digests alcohol (Wuethrich, 2001). They can become addicted to alcohol more quickly than boys and young men. They also suffer lung, brain, and liver damage at lower consumption levels (CASA, 2003) (FIGURE 13.3).

barbiturates drugs that depress central nervous system activity, reducing anxiety but impairing memory and judgment.

BARBITURATES Like alcohol, the barbiturate drugs, or tranquilizers, depress nervous system activity. Barbiturates such as Nembutal, Seconal, and Amytal are sometimes prescribed to induce sleep or reduce anxiety. In larger doses, they can impair memory and judgment. If combined with alcohol, the total depressive effect on body functions can lead to death. This sometimes happens when people take a sleeping pill after an evening of heavy drinking.

opiates opium and its derivatives, such as morphine and heroin; depress neural activity, temporarily lessening pain and anxiety.

OPIATESThe opiates—opium and its offshoots—

Retrieve + Remember

Question 13.12

•Can someone become “addicted” to shopping?

ANSWER: Unless it becomes compulsive or dysfunctional, simply having a strong interest in shopping is not the same as having a physical addiction to a drug. It does not involve obsessive craving in spite of known negative consequences.

Question 13.13

•Alcohol, barbiturates, and opiates are all in a class of drugs called ____.

ANSWER: depressants

Stimulants

LOQ 13-

stimulants drugs (such as caffeine, nicotine, and the more powerful cocaine, amphetamines, methamphetamine, and Ecstasy) that excite neural activity and speed up body functions.

A stimulant excites neural activity and speeds up body functions. Pupils dilate. Heart and breathing rates increase. Blood-

Stimulants include caffeine, nicotine, and the more powerful cocaine, amphetamines, methamphetamine, and Ecstasy. People use stimulants to feel alert, lose weight, or boost mood or athletic performance. Unfortunately, stimulants can be addictive, as you may know if you are one of the many who use caffeine daily in your coffee, tea, soda, or energy drinks. Cut off from your usual dose, you may crash into fatigue, headaches, irritability, and depression (Silverman et al., 1992). A mild dose of caffeine typically lasts three or four hours, which—

nicotine a stimulating and highly addictive psychoactive drug in tobacco.

NICOTINEOne of the most addictive stimulants is nicotine, found in cigarettes, e-

| Marijuana | 9% |

| Alcohol | 15 |

| Cocaine | 17 |

| Heroin | 23 |

| Tobacco | 32 |

Source: National Academy of Science, Institute of Medicine (Brody, 2003).

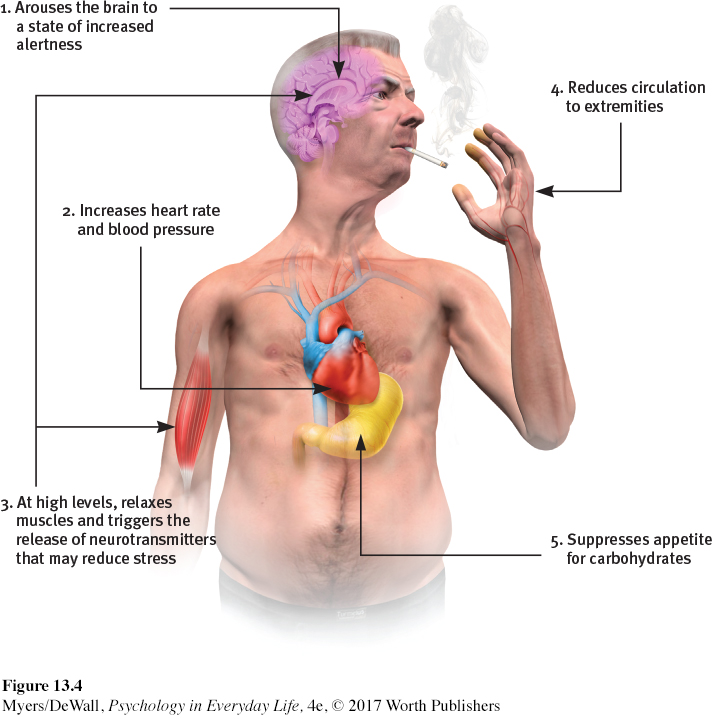

Within 7 seconds (twice as fast as intravenous heroin), a rush of nicotine will signal the central nervous system to release a flood of neurotransmitters (FIGURE 13.4). Epinephrine and norepinephrine will diminish appetite and boost alertness and mental efficiency. Dopamine and opioids will calm anxiety and reduce sensitivity to pain (Ditre et al., 2011; Gavin, 2004). No wonder some ex-

These rewards keep people smoking, even among the 3 in 4 smokers who wish they could stop (Newport, 2013b). Each year, fewer than 1 in 7 who want to quit will be able to resist. Smokers die, on average, at least a decade before nonsmokers, but even those who know they are committing slow-

The good news is that repeated attempts to quit smoking seem to pay off. Half of all Americans who have ever smoked have quit, some with the aid of a nicotine replacement drug and a support group. Success is equally likely whether smokers quit abruptly or gradually (Fiore et al., 2008; Lichtenstein et al., 2010; Lindson et al., 2010). The acute craving and withdrawal symptoms do go away gradually over six months (Ward et al., 1997). After a year’s abstinence, only 10 percent return to smoking in the next year (Hughes et al., 2008).

Retrieve + Remember

Question 13.14

•What withdrawal symptoms should your friend expect when she finally decides to quit smoking?

ANSWER: Nicotine-

cocaine a powerful and addictive stimulant derived from the coca plant; temporarily increases alertness and produces feelings of euphoria.

COCAINE Cocaine is a powerful and addictive stimulant derived from the coca plant. The recipe for Coca-

Cocaine use may heighten reactions, such as aggression (Licata et al., 1993). It may also lead to emotional disturbances, suspiciousness, convulsions, cardiac arrest, or respiratory failure. The drug’s psychological effects depend in part on the dosage and form consumed, but the situation and the user’s expectations and personality also play a role. Given a placebo, cocaine users who thought they were taking cocaine often had a cocaine-

amphetamines drugs that stimulate neural activity, causing speeded-

methamphetamine a powerfully addictive drug that stimulates the central nervous system with speeded-

METHAMPHETAMINE Amphetamines stimulate neural activity. As body functions speed up, the user’s energy rises and mood soars. Amphetamines are the parent drug for the highly addictive methamphetamine, which is chemically similar but has greater effects (NIDA, 2002, 2005). Methamphetamine triggers the release of the neurotransmitter dopamine, which stimulates brain cells that enhance energy and mood. Eight or so hours of heightened energy and mood then follow. Aftereffects may include irritability, insomnia, high blood pressure, seizures, social isolation, depression, and occasional violent outbursts (Homer et al., 2008). Over time, methamphetamine may reduce the brain’s normal output of dopamine.

Ecstasy (MDMA) a synthetic stimulant and mild hallucinogen. Produces euphoria and social intimacy, but with short-

ECSTASY Ecstasy is the street name for MDMA (methylenedioxymethamphetamine, also known in its powdered form as “Molly”). This powerful drug is both a stimulant and a mild hallucinogen. (Hallucinogens distort perceptions and lead to false sensory images. More on that later.) Ecstasy is an amphetamine derivative that triggers the brain’s release of dopamine. But its major effect is releasing stored serotonin and blocking its reuptake, thus prolonging serotonin’s feel-

During the late 1990s, Ecstasy’s popularity soared as a “club drug” taken at nightclubs and all-

Hallucinogens

LOQ 13-

hallucinogens psychedelic (“mind-

Hallucinogens distort perceptions and call up sensory images (such as sounds or sights) without any input from the senses. This helps explain why these drugs are also called psychedelics, meaning “mind-

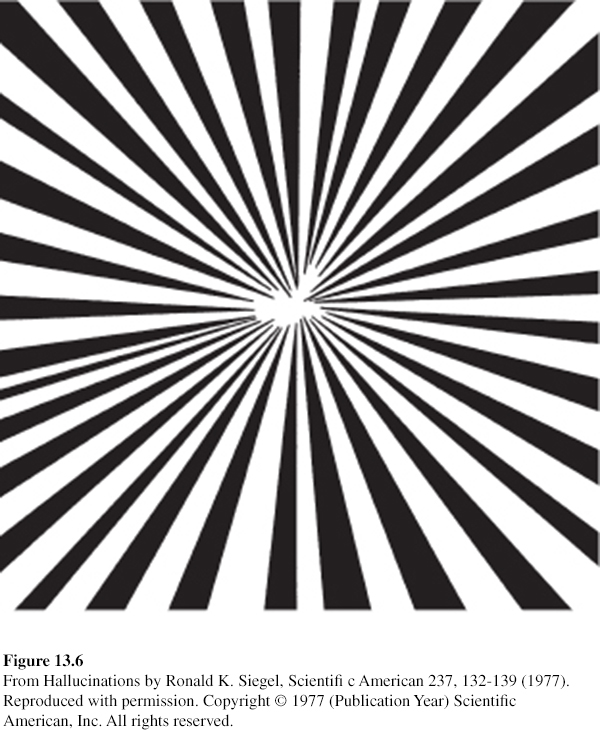

Whether provoked to hallucinate by drugs, loss of oxygen, or extreme sensory deprivation, the brain hallucinates in basically the same way (Siegel, 1982). The experience typically begins with simple geometric forms, such as a criss-

near-

These sensations are strikingly similar to the near-

LSD a powerful hallucinogenic drug; also known as acid (lysergic acid diethylamide).

LSD In 1943, Albert Hofmann reported perceiving “an uninterrupted stream of fantastic pictures, extraordinary shapes with an intense, kaleidoscopic play of colors” (Siegel, 1984). Hofmann, a chemist, had created and accidentally ingested LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide). LSD, like Ecstasy, interferes with the serotonin neurotransmitter system. An LSD “trip” can take users to unexpected places. Emotions may vary from euphoria to detachment to panic, depending in part on the person’s mood and expectations.

THC the major active ingredient in marijuana; triggers a variety of effects, including mild hallucinations.

MARIJUANA For 5000 years, hemp has been cultivated for its fiber. The leaves and flowers of this plant, which are sold as marijuana, contain THC (delta-

The straight dope on marijuana: It is usually classified as a mild hallucinogen, because it increases sensitivity to colors, sounds, tastes, and smells. But in other ways, marijuana is like alcohol. It relaxes, disinhibits, and may produce a euphoric high. And, like alcohol, it impairs motor coordination, perceptual skills, and reaction time, so it interferes with safe operation of an automobile or other machine. “THC causes animals to misjudge events,” reported Ronald Siegel (1990, p. 163). “Pigeons wait too long to respond to buzzers or lights that tell them food is available for brief periods; and rats turn the wrong way in mazes.”

Marijuana and alcohol also differ. The body eliminates alcohol within hours. THC and its by-

A marijuana user’s experience can vary with the situation. If the person feels anxious or depressed, marijuana may intensify these feelings. The more often the person uses marijuana, the greater the risk of anxiety, depression, or addiction (Bambico et al., 2010; Hurd et al., 2013; Murray et al., 2007).

Does marijuana harm the brain and impair cognition? Some evidence indicates that it disrupts memory formation (Bossong et al., 2012). Such effects on thinking outlast the period of smoking (Messinis et al., 2006). Heavy adult use for over 20 years has been associated with shrinkage of brain areas that process memories and emotions (Filbey et al., 2014; Yücel et al., 2008). And one long-

In some cases, medical marijuana use has been legalized as treatment for the pain and nausea associated with diseases such as AIDS and cancer (Munsey, 2010; Watson et al., 2000). In such treatments, the Institute of Medicine recommends delivering the THC with medical inhalers. Marijuana smoke, like cigarette smoke, is toxic and can cause cancer, lung damage, and pregnancy complications (BLF, 2012).

* * *

TABLE 13.5 summarizes the psychoactive drugs discussed in this section. They share some features. All trigger negative aftereffects that offset their immediate positive effects and grow stronger with repetition. This helps explain both tolerance and withdrawal. As the negative aftereffects grow stronger, larger and larger doses are typically needed to produce the desired high (tolerance). These increasingly larger doses produce even worse aftereffects in the drug’s absence (withdrawal). The worsening aftereffects, in turn, create a need to switch off the withdrawal symptoms by taking yet more of the drug.

| Drug | Type | Pleasurable Effects | Negative Aftereffects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | Depressant | Initial high followed by relaxation and disinhibition | Depression, memory loss, organ damage, impaired reactions |

| Heroin | Depressant | Rush of euphoria, relief from pain | Depressed physiology, agonizing withdrawal |

| Caffeine | Stimulant | Increased alertness and wakefulness | Anxiety, restlessness, and insomnia in high doses; uncomfortable withdrawal |

| Nicotine | Stimulant | Arousal and relaxation, sense of well- |

Heart disease, cancer |

| Cocaine | Stimulant | Rush of euphoria, confidence, energy | Cardiovascular stress, suspiciousness, depressive crash |

| Methamphetamine | Stimulant | Euphoria, alertness, energy | Irritability, insomnia, hypertension, seizures |

| Ecstasy (MDMA) | Stimulant; mild hallucinogen | Emotional elevation, disinhibition | Dehydration, overheating, depressed mood, impaired cognitive and immune functioning |

| LSD | Hallucinogen | Visual “trip” | Risk of panic |

| Marijuana (THC) | Mild hallucinogen | Enhanced sensation, relief of pain, distortion of time, relaxation | Impaired learning and memory, increased risk of psychological disorders, lung damage from smoke |

Retrieve + Remember

Question 13.15

“How strange would appear to be this thing that men call pleasure! And how curiously it is related to what is thought to be its opposite, pain! . . . Wherever the one is found, the other follows up behind.”

Plato, Phaedo, fourth century B.C.E.

•How does this pleasure-

ANSWER: Psychoactive drugs create pleasure by altering brain chemistry. With repeated use of the drug, the brain develops tolerance and needs more of the drug to achieve the desired effect. (Marijuana is an exception.) Discontinuing use of the substance then produces painful or psychologically unpleasant withdrawal symptoms.

To review the basic psychoactive drugs and their actions, and to play the role of experimenter as you administer drugs and observe their effects, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Your Mind on Drugs.

To review the basic psychoactive drugs and their actions, and to play the role of experimenter as you administer drugs and observe their effects, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Your Mind on Drugs.

Understanding Substance Use Disorders

LOQ 13-

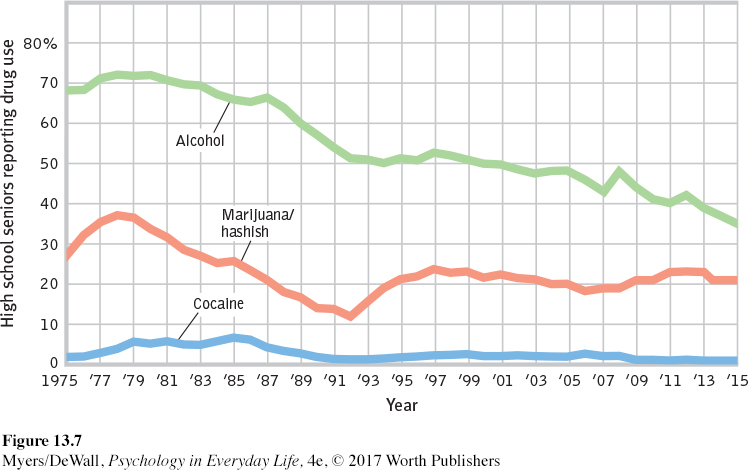

Substance use by North American youth increased during the 1970s. Then, with increased drug education and a shift toward more realism and less glamorous media portrayals of the effects of drugs, substance use declined sharply, except for a small, brief rebound in the mid-

For many adolescents, occasional drug use represents thrill seeking. Yet why do some adolescents, but not others, become regular drug users? In search of answers, researchers have tried to sort out biological, psychological, and social-

Biological Influences

Are some of us biologically vulnerable to particular drugs? Evidence indicates we are (Crabbe, 2002):

For identical twins, if one twin is diagnosed with alcohol use disorder, the other also has an increased risk for alcohol problems. In marijuana use, too, identical twins more closely resemble each other (Kendler et al., 2002c). This increased risk is not found among fraternal twins.

Researchers have identified genes associated with alcohol use disorder, and they are seeking genes that contribute to tobacco addiction (Stacey et al., 2012). These culprit genes seem to produce deficiencies in the brain’s natural dopamine reward system.

A large study of 18,115 adopted people also found evidence of both a genetic influence and an environmental influence. Those with drug-

abusing biological parents were at doubled risk of drug abuse. But those with a drug- abusing adoptive sibling also had a doubled risk of drug abuse (Kendler et al., 2012). So, what might those environmental influences be?

Psychological and Social-Cultural Influences

Throughout this text, you have seen a recurring theme: Biological, psychological, and social-

Sometimes, a psychological influence is obvious. Many heavy users of alcohol, marijuana, and cocaine have experienced significant stress or failure and are depressed. Girls with a history of depression, eating disorders, or sexual or physical abuse are at risk for substance addiction. So are youth undergoing school or neighborhood transitions (CASA, 2003; Logan et al., 2002). By temporarily dulling the pain of self-

Rates of substance use also vary across cultural and ethnic groups. Among actively religious people, alcohol and other substance addiction rates have been low, with extremely low rates among Orthodox Jews, Mormons, Mennonites, and the Amish (Salas-

Substance use can also have social roots. Adolescents, self-

Whether in cities or in rural areas, peers influence attitudes about substance use. They throw the parties and provide (or don’t provide) the drugs. If an adolescent’s friends abuse drugs, the odds are that he or she will, too. If the friends do not, the opportunity may not even arise.

Peer influence is more than what friends do and say. Adolescents’ expectations—

Teens rarely abuse drugs if they understand the physical and psychological costs, do well in school, feel good about themselves, and are in a peer group that disapproves of early drinking and using drugs (Bachman et al., 2007; Hingson et al., 2006). These findings suggest three tactics for preventing and treating substance use and addiction among young people:

Educate them about the long-

term costs of a drug’s temporary pleasures. Boost their self-

esteem and help them discover their purpose in life. Attempt to modify peer associations or to “inoculate” youth against peer pressures by training them in refusal skills.

Retrieve + Remember

Question 13.16

•Studies have found that people who begin drinking in their early teens are much more likely to develop alcohol use disorder than are those who begin at age 21 or after. What possible explanations might there be for this correlation?

ANSWER: Possible explanations include (a) biological factors (a person could have a biological predisposition to both early use and later abuse, or alcohol use could modify a person’s neural pathways); (b) psychological factors (early use could establish taste preferences for alcohol); and (c) social-