13.6 Other Disorders

Eating Disorders

LOQ 13-

Our bodies are naturally disposed to maintain a steady weight, storing energy reserves in case food becomes unavailable. But psychological influences can overwhelm biological wisdom. Nowhere is this more painfully clear than in eating disorders.

anorexia nervosa an eating disorder in which a person (usually an adolescent female) maintains a starvation diet despite being significantly underweight; sometimes accompanied by excessive exercise.

In anorexia nervosa, people—

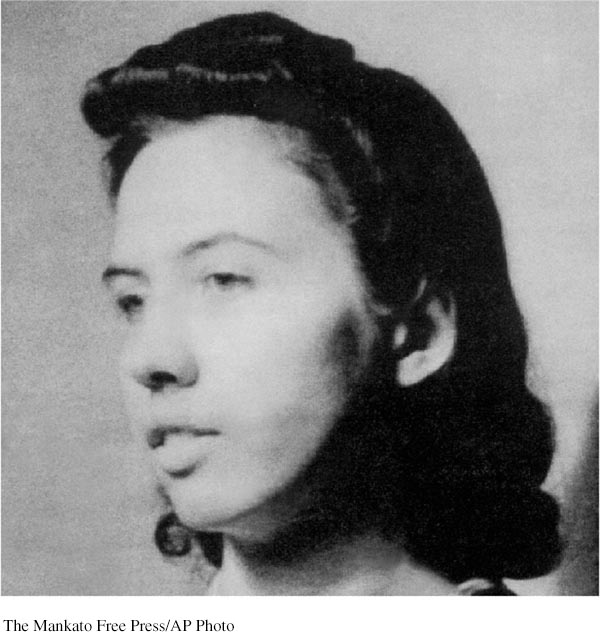

usually female adolescents, but some women, men, and boys as well— starve themselves. Anorexia often begins as an attempt to lose weight, but the dieting doesn’t end. Even when far below normal weight, the self- starved person feels fat, fears being fat, and focuses obsessively on losing weight, sometimes exercising excessively. At some point in their lifetime, 0.6 percent of Americans meet the criteria for anorexia nervosa (Hudson et al., 2007).  SIBLING RIVALRY TO THE EXTREME Twins Maria and Katy Campbell have anorexia nervosa. As children they competed to see who could be thinner. Now, says Maria, her anorexia nervosa is “like a ball and chain around my ankle that I can’t throw off” (Foster, 2011).© Nick Holt PhotographyPage 406

SIBLING RIVALRY TO THE EXTREME Twins Maria and Katy Campbell have anorexia nervosa. As children they competed to see who could be thinner. Now, says Maria, her anorexia nervosa is “like a ball and chain around my ankle that I can’t throw off” (Foster, 2011).© Nick Holt PhotographyPage 406bulimia nervosa an eating disorder in which a person alternates binge eating (usually of high-

calorie foods) with purging (by vomiting or laxative use) or fasting. In bulimia nervosa, food binges alternate with purges (vomiting and laxative use), sometimes followed by fasting and excessive exercise. Unlike anorexia, bulimia is marked by weight shifts within or above normal ranges, making this disorder easier to hide. Binge-

purge eaters are preoccupied with food (especially sweet and high- fat foods) and obsessed with their weight and appearance. They experience bouts of guilt, depression, and anxiety, especially during and following binges (Hinz & Williamson, 1987; Johnson et al., 2002). About 1 percent of Americans, mostly women in their late teens or early twenties (but also some men), have had bulimia. binge-

eating disorder significant bingeeating episodes, followed by distress, disgust, or guilt, but without the purging or fasting that marks bulimia nervosa.Those with binge-

eating disorder engage in significant bouts of overeating, followed by remorse. But they do not purge, fast, or exercise excessively, and so may be overweight. At some point during their lifetime, 2.8 percent of Americans have had binge-eating disorder (Hudson et al., 2007).

Understanding Eating Disorders

So, how can we explain eating disorders? Heredity matters. Identical twins share these disorders somewhat more often than fraternal twins do (Culbert et al., 2009; Klump et al., 2009; Root et al., 2010). Scientists are searching for culprit genes. Data from 15 studies indicate that having a gene that reduces available serotonin adds 30 percent to a person’s risk of anorexia or bulimia (Calati et al., 2011).

But environment also matters. People with anorexia come from families that tend to be competitive, high-

Our environment includes our culture and our history. Ideal shapes vary across culture and time. In areas with high rates of poverty—

Bigger does not seem better in Western cultures, where the rise in eating disorders over the last 50 years has coincided with a dramatic increase in women having a poor body image (Feingold & Mazzella, 1998). Those most vulnerable to eating disorders are also those (usually women or gay men) who most idealize thinness and have the greatest body dissatisfaction (Feldman & Meyer, 2010; Kane, 2010; Stice et al., 2010). Part of the pressure stems from images of unnaturally thin models and celebrities (Tovee et al., 1997). One former model recalled walking into a meeting with her agent, starving and with her organs failing as a result of anorexia (Caroll, 2013). Her agent’s greeting: “Whatever you are doing, keep doing it.”

Should it surprise us, then, that women who view such images often feel ashamed, depressed, and dissatisfied with their own bodies (Myers & Crowther, 2009; Tiggeman & Miller, 2010)? In one study, researchers tested media influences by giving some adolescent girls (but not others) a 15-

Some critics point out that there’s much more to body dissatisfaction and anorexia than media effects (Ferguson et al., 2011). Peer influences, such as teasing, also matter. Nevertheless, the sickness of today’s eating disorders stems in part from today’s weight-

If cultural learning contributes to eating behavior, could prevention programs increase acceptance of one’s body? Prevention studies answer Yes. They seem especially effective if the programs are interactive and focused on girls over age 15 (Beintner et al., 2012; Melioli et al., 2016; Vocks et al., 2010).

Retrieve + Remember

Question 13.20

•People with _____ (anorexia nervosa/bulimia nervosa) continue to want to lose weight even when they are underweight. Those with _____ (anorexia nervosa/bulimia nervosa) tend to have weight that fluctuates within or above normal ranges.

ANSWERS: anorexia nervosa; bulimia nervosa

Dissociative Disorders

LOQ 13-

dissociative disorders controversial, rare disorders in which conscious awareness becomes separated (dissociated) from previous memories, thoughts, and feelings.

Among the most bewildering disorders are the rare dissociative disorders. The person’s conscious awareness is said to become separated—dissociated—

dissociative identity disorder (DID) a rare dissociative disorder in which a person exhibits two or more distinct and alternating personalities. (Formerly called multiple personality disorder.)

Dissociation itself is not so rare. Any one of us may have a fleeting sense of being unreal, of being separated from our body, of watching ourselves as if in a movie. But a massive dissociation of self from ordinary consciousness occurs in dissociative identity disorder (DID—formerly called multiple personality disorder). At different times, two or more distinct identities seem to control the person’s behavior, each with its own voice and mannerisms. Thus, the person may be prim and proper one moment, loud and flirtatious the next. Typically, the original personality denies any awareness of the other(s).

Skeptics question the genuineness of DID. First, they find it suspicious that DID has such a short history. Between 1930 and 1960, the number of North American DID diagnoses was 2 per decade. By the 1980s, when the DSM contained the first formal code for this disorder, the number had exploded to more than 20,000 (McHugh, 1995b). The average number of displayed personalities also mushroomed—

Second, note skeptics, DID rates vary by culture. It is much less common outside North America, although in other cultures some people are said to be “possessed” by an alien spirit (Aldridge-

Third, some skeptics have asked, could DID be an extension of our normal capacity for personality shifts? Perhaps dissociative identities are simply a more extreme version of the varied “selves” we normally present, as when we display a goofy, loud self while hanging out with friends, and a subdued, respectful self around grandparents. If so, say the critics, clinicians who discover multiple personalities may merely have triggered role playing by fantasy-

Other researchers and clinicians believe DID is a real disorder. They cite findings of distinct brain and body states associated with differing personalities (Putnam, 1991). People with DID exhibit increased activity in brain areas linked with the control and inhibition of traumatic memories (Elzinga et al., 2007). Brain scans show shrinkage in other areas that aid memory and threat detection (Vermetten et al., 2006).

Understanding Dissociative Identity Disorder

If DID is a real disorder, how can we best understand it? Both the psychodynamic and the learning perspectives have interpreted DID symptoms as ways of coping with anxiety. Some psychodynamic theorists see them as defenses against the anxiety caused by unacceptable impulses. In this view, a second personality could allow the discharge of forbidden impulses. Learning theorists see dissociative disorders as behaviors reinforced by anxiety reduction.

Some clinicians include dissociative disorders under the umbrella of posttraumatic stress disorder. In this view, DID is a natural, protective response to traumatic experiences during childhood (Dalenberg et al., 2012). Many people with DID recall suffering physical, sexual, or emotional abuse as children (Gleaves, 1996; Lilienfeld et al., 1999). In one study of 12 murderers diagnosed with DID, 11 had suffered severe abuse, even torture, in childhood (Lewis et al., 1997). One had been set afire by his parents. Another had been used in child pornography and was scarred from being made to sit on a stove burner. Some critics wonder, however, whether vivid imagination or therapist suggestion contributes to such recollections (Kihlstrom, 2005).

So the debate continues. On one side are those who believe multiple personalities are the desperate efforts of people trying to detach from a horrific existence. On the other are the skeptics who think DID is constructed out of the therapist-

Retrieve + Remember

Question 13.21

•The psychodynamic and learning perspectives agree that dissociative identity disorder symptoms are ways of dealing with anxiety. How do their explanations differ?

ANSWER: The psychodynamic explanation of DID symptoms is that they are defenses against anxiety generated by unacceptable urges. The learning perspective attempts to explain these symptoms as behaviors that have been reinforced by relieving anxiety.

Personality Disorders

LOQ 13-

personality disorder an inflexible and enduring behavior pattern that impairs social functioning.

There is little debate about the reality of personality disorders. These inflexible and enduring behavior patterns interfere with a person’s ability to function socially. Some people with these disorders are anxious and withdrawn, and they avoid social contact. Some behave in eccentric or odd ways, or interact without engaging emotionally. Others seem overly dramatic or impulsive, focusing attention on themselves.

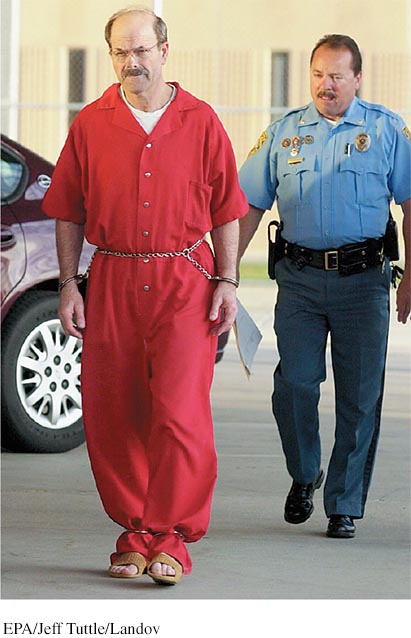

antisocial personality disorder a personality disorder in which a person (usually a man) exhibits a lack of conscience for wrongdoing, even toward friends and family members; may be aggressive and ruthless or a clever con artist.

The most troubling and heavily researched personality disorder is antisocial personality disorder. People with this disorder are typically males whose lack of conscience becomes plain before age 15, as they begin to lie, steal, fight, or display unrestrained sexual behavior (Cale & Lilienfeld, 2002). They behave impulsively and then feel and fear little (Fowles & Dindo, 2009). Not all children with these traits become antisocial adults. Those who do (about half of them) will generally act in violent or otherwise criminal ways, be unable to keep a job, and, if they have a spouse or children, behave irresponsibly toward them (Farrington, 1991). People with antisocial personality (sometimes called sociopaths or psychopaths) may show lower emotional intelligence—

Antisocial does not necessarily mean criminal (Skeem & Cooke, 2010). When lack of conscience combines with keen intelligence, the result may be a charming and clever con artist—

But do all criminals have antisocial personality disorder? Definitely not. Most criminals show responsible concern for their friends and family members.

Understanding Antisocial Personality Disorder

Antisocial personality disorder is woven of both biological and psychological strands. No single gene codes for a complex behavior such as crime. There is, however, a genetic tendency toward a fearless and uninhibited life. Twin and adoption studies reveal that biological relatives of people with antisocial and unemotional tendencies are at increased risk for antisocial behavior (Frisell et al., 2012; Tuvblad et al., 2011).

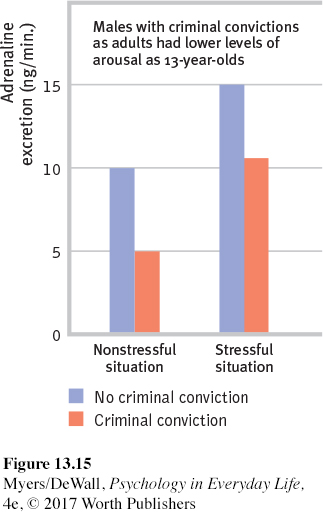

Genetic influences and negative environmental factors (such as childhood abuse, family instability, or poverty) can work together to help wire the brain (Dodge, 2009). The genetic vulnerability of those with antisocial and unemotional tendencies appears as low arousal. Awaiting events that most people would find unnerving, such as electric shocks or loud noises, they show little bodily arousal (Hare, 1975; van Goozen et al., 2007). Long-

Other brain activity differences appear in studies of antisocial criminals. Shown photographs that would produce an emotional response in most people (such as a man holding a knife to a woman’s throat), antisocial criminals’ heart rate and perspiration responses are lower than normal, and brain areas that typically respond to emotional stimuli are less active (Harenski et al., 2010; Kiehl & Buckholtz, 2010). Other studies have found that people with antisocial criminal tendencies have a smaller-

One study compared PET scans of 41 murderers’ brains with those from people of similar age and sex. The murderers’ frontal lobe, an area that helps control impulses, displayed reduced activity (Raine, 1999, 2005). This reduction was especially apparent in those who murdered impulsively. In a follow-

Retrieve + Remember

Question 13.22

•How do biological and psychological factors contribute to antisocial personality disorder?

ANSWER: Twin and adoption studies show that biological relatives of people with this disorder are at increased risk for antisocial behavior. Researchers have also observed differences in the brain activity and structure of antisocial criminals. Negative environmental factors, such as poverty or childhood abuse, may channel genetic traits such as fearlessness in more dangerous directions—