14.2 The Psychological Therapies

eclectic approach an approach to psychotherapy that, depending on the client’s problems, uses techniques from various forms of therapy.

Among the dozens of psychotherapies, we will focus on the most influential. Each is built on one or more of psychology’s major theories: psychodynamic, humanistic, behavioral, and cognitive. Most of these techniques can be used one-

Psychoanalysis and Psychodynamic Therapy

LOQ 14-

psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud’s therapeutic technique. Freud believed that the patient’s free associations, resistances, dreams, and transferences—

The first major psychological therapy was Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis. Although few clinicians today practice therapy as Freud did, his work deserves discussion. It helped form the foundation for treating psychological disorders, and it continues to influence modern therapists working from the psychodynamic perspective.

The Goals of Psychoanalysis

Freud believed that in therapy, people could achieve healthier, less anxious living by releasing the energy they had previously devoted to id-

Freud’s therapy aimed to bring patients’ repressed feelings into conscious awareness. By helping them reclaim their unconscious thoughts and feelings, the therapist (analyst) would also help them gain insight into the origins of their disorders. This insight could in turn inspire them to take responsibility for their own growth.

The Techniques of Psychoanalysis

Psychoanalytic theory emphasizes the power of childhood experiences to mold us. Thus, its main method is historical reconstruction. It aims to unearth the past in the hope of loosening its bonds on the present. After trying and discarding hypnosis as a possible excavating tool, Freud turned to free association.

Imagine yourself as a patient using free association. You begin by relaxing, perhaps by lying on a couch. The psychoanalyst, who sits out of your line of vision, asks you to say aloud whatever comes to mind. At one moment, you’re relating a childhood memory. At another, you’re describing a dream or recent experience.

It sounds easy, but soon you notice how often you edit your thoughts as you speak. You pause for a second before describing an embarrassing thought. You skip things that seem trivial, off point, or shameful. Sometimes your mind goes blank, unable to remember important details. You may joke or change the subject to something less threatening.

resistance in psychoanalysis, the blocking from consciousness of anxiety-

interpretation in psychoanalysis, the analyst’s noting supposed dream meanings, resistances, and other significant behaviors and events in order to promote insight.

To an analyst, these mental blips are blocks that indicate resistance. They hint that anxiety lurks and you are defending against sensitive material. The analyst will note your resistance and then provide insight into its meaning. If offered at the right moment, this interpretation—of, say, your not wanting to talk about your mother or call, text, or message her—

transference in psychoanalysis, the patient’s transfer to the analyst of emotions linked with other relationships (such as love or hatred for a parent).

Multiply that one session by dozens and your relationship patterns will surface in your interactions with your analyst. You may find you have strong positive or negative feelings for your analyst. The analyst may suggest you are transferring feelings, such as dependency or mingled love and anger, that you experienced in earlier relationships with family members or other important people. By exposing such feelings, you may gain insight into your current relationships.

Relatively few U.S. therapists now offer traditional psychoanalysis. Much of its underlying theory is not supported by scientific research (Chapter 12). Analysts’ interpretations do not follow the scientific method—

Retrieve + Remember

Question 14.1

•In psychoanalysis, when patients experience strong feelings for their analyst, this is called _______. Patients are said to demonstrate anxiety when they put up mental blocks around sensitive memories, showing _______. The analyst will attempt to provide insight into the underlying anxiety by offering a(n) _______ of the mental blocks.

ANSWERS: transference; resistance; interpretation

Psychodynamic Therapy

psychodynamic therapy therapeutic approach derived from the psychoanalytic tradition; views individuals as responding to unconscious forces and childhood experiences, and seeks to enhance self-

Although influenced by Freud’s ideas, psychodynamic therapists don’t talk much about id, ego, and superego. Instead, they try to help people understand their current symptoms by focusing on themes across important relationships, including childhood experiences and the therapist-

In these meetings, clients explore and gain perspective on defended-

Therapist: Do you mean, then, that if you could, you would like to?

Patient: Well, I don’t know. . . . Maybe I can’t say it because I’m not sure it’s true. Maybe I don’t love her.

Further interactions revealed that the client could not express real love because it would feel “mushy” and “soft” and therefore unmanly. The therapist noted that this young man was “in conflict with himself, and . . . cut off from the nature of that conflict.” With such patients, who are estranged from themselves, therapists using psychodynamic techniques “are in a position to introduce them to themselves. We can restore their awareness of their own wishes and feelings, and their awareness, as well, of their reactions against those wishes and feelings” (Shapiro, 1999, p. 8).

Exploring past relationship troubles may help clients understand the origin of their current difficulties. Another therapist (Shedler, 2010a) recalled a client’s complaints of difficulty getting along with his colleagues and wife, who saw him as overly critical. The client, “Jeffrey,” then “began responding to me as if I were an unpredictable, angry adversary.” Seizing the opportunity to help Jeffrey recognize the relationship pattern, the therapist helped him explore the pattern’s roots in the attacks and humiliation he had experienced from his father. Jeffrey was then able to work through and let go of this defensive style of responding to people. Without embracing all aspects of Freud’s theory, psychodynamic therapists aim to help people gain insight into their childhood experiences and unconscious dynamics.

Humanistic Therapies

LOQ 14-

insight therapies therapies that aim to improve psychological functioning by increasing a person’s awareness of underlying motives and defenses.

The humanistic perspective (Chapter 12) emphasizes people’s innate potential for self-

Humanistic therapists aim to boost people’s self-

fulfillment by helping them grow in self- awareness and self- acceptance. Promoting growth, not curing illness, is the therapy focus. Thus, those in therapy become “clients” or just “persons” rather than “patients” (a change many other therapists have adopted).

The path to growth is taking immediate responsibility for one’s feelings and actions, rather than uncovering hidden causes.

Conscious thoughts are more important than the unconscious.

The present and future are more important than the past. Therapy thus focuses on exploring feelings as they occur, rather than on gaining insights into the childhood origins of those feelings.

person-

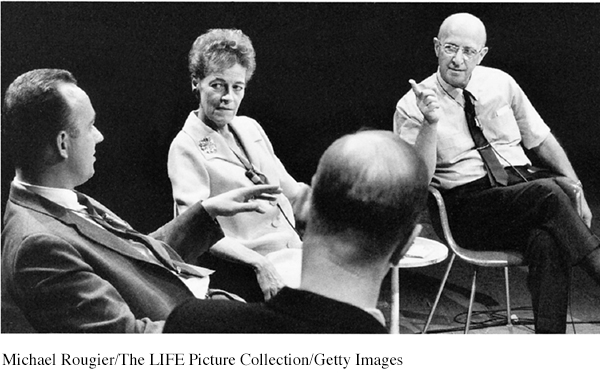

All these themes are present in a widely used humanistic technique developed by Carl Rogers (1902–

Rogers (1961, 1980) believed that most people already possess the resources for growth. He encouraged therapists to foster growth by exhibiting genuineness, acceptance, and empathy. By being genuine, therapists hope to encourage clients to likewise express their true feelings. By being accepting, therapists may help clients feel freer and more open to change. By showing empathy—

Hearing has consequences. When I truly hear a person and the meanings that are important to him at that moment, hearing not simply his words, but him, and when I let him know that I have heard his own private personal meanings, many things happen. There is first of all a grateful look. He feels released. He wants to tell me more about his world. He surges forth in a new sense of freedom. He becomes more open to the process of change.

I have often noticed that the more deeply I hear the meanings of the person, the more there is that happens. Almost always, when a person realizes he has been deeply heard, his eyes moisten. I think in some real sense he is weeping for joy. It is as though he were saying, “Thank God, somebody heard me. Someone knows what it’s like to be me.”

active listening empathic listening in which the listener echoes, restates, and clarifies. A feature of Rogers’ person-

To Rogers, “hearing” was active listening. The therapist echoes, restates, and clarifies what the client expresses (verbally or nonverbally). The therapist also acknowledges those expressed feelings. Active listening is now an accepted part of counseling practices in many schools, colleges, and clinics. Counselors listen attentively. They interrupt only to restate and confirm feelings, to accept what was said, or to check their understanding of something. In the following brief excerpt, note how Rogers tried to provide a psychological mirror that would help the client see himself more clearly.

Rogers: Feeling that now, hm? That you’re just no good to yourself, no good to anybody. Never will be any good to anybody. Just that you’re completely worthless, huh?—Those really are lousy feelings. Just feel that you’re no good at all, hm?

Client: Yeah. (Muttering in low, discouraged voice) That’s what this guy I went to town with just the other day told me.

Rogers: This guy that you went to town with really told you that you were no good? Is that what you’re saying? Did I get that right?

Client: M-

Rogers: I guess the meaning of that if I get it right is that here’s somebody that meant something to you and what does he think of you? Why, he’s told you that he thinks you’re no good at all. And that just really knocks the props out from under you. (Client weeps quietly.) It just brings the tears. (Silence of 20 seconds)

Client: (Rather defiantly) I don’t care though.

Rogers: You tell yourself you don’t care at all, but somehow I guess some part of you cares because some part of you weeps over it. (Meador & Rogers, 1984, p. 167)

unconditional positive regard a caring, accepting, nonjudgmental attitude, which Rogers believed would help clients develop self-

Can a therapist be a perfect mirror, critics have asked, without selecting and interpreting what is reflected? Rogers granted that no one can be totally nondirective. Nevertheless, he said, the therapist’s most important contribution is to accept and understand the client. Given a nonjudgmental, grace-

How can we improve communication in our own relationships by listening more actively? Three Rogerian hints may help:

Summarize. Check your understanding by repeating the other person’s statements in your own words.

Invite clarification. “What might be an example of that?” may encourage the person to say more.

Reflect feelings. “It sounds frustrating” might mirror what you’re sensing from the person’s body language and emotional intensity.

Behavior Therapies

LOQ 14-

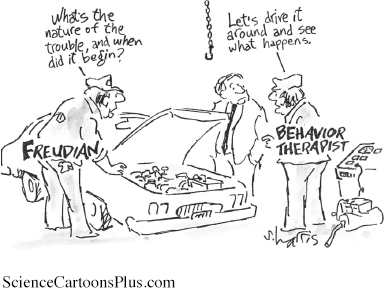

The insight therapies assume that self-

Psychodynamic therapies assume people’s problems will lessen as they gain insight into their unresolved and unconscious tensions.

Humanistic therapies assume people’s problems will lessen as they get in touch with their feelings.

behavior therapy a therapeutic approach that applies learning principles to the elimination of unwanted behaviors.

Behavior therapies, however, take a different approach. Rather than searching beneath the surface for inner causes, they assume that problem behaviors are the problems. (You can become aware of why you are highly anxious during exams and still be anxious.) By harnessing the power of learning principles, behavior therapists offer clients useful tools for getting rid of unwanted behaviors. They view phobias, for example, as learned behaviors. So why not use conditioning techniques to replace them with new behaviors?

Classical Conditioning Techniques

One cluster of behavior therapies draws on principles developed in Ivan Pavlov’s conditioning experiments (Chapter 6). As Pavlov and others showed, we learn various behaviors and emotions through classical conditioning. If we’re attacked by a dog, we may thereafter have a conditioned fear response when other dogs approach. (Our fear generalizes, and all dogs become conditioned stimuli.)

Could other unwanted responses also be explained by conditioning? If so, might reconditioning be a solution? Learning theorist O. H. Mowrer thought so. He developed a successful conditioning therapy for chronic bed-

counterconditioning behavior therapy procedures that use classical conditioning to evoke new responses to stimuli that are triggering unwanted behaviors; includes exposure therapies and aversive conditioning.

Let’s broaden the discussion. What triggers your worst fear responses? Public speaking? Flying? Tight spaces? Circus clowns? Whatever the trigger, do you think you could unlearn your fear responses? With new conditioning, many people have. An example: The fear of riding in an elevator is often a learned response to the stimulus of being confined in a tight space. Therapists have successfully counterconditioned people with a fear of confined spaces. They pair the trigger stimulus (the enclosed space of the elevator) with a new response (relaxation) that cannot coexist with fear.

To replace unwanted responses with new responses, therapists may use exposure therapies and aversive conditioning.

EXPOSURE THERAPIES Picture the animal you fear the most. Maybe it’s a snake, a spider, or even a cat or a dog. For 3-

As Peter began his midafternoon snack, she introduced a caged rabbit on the other side of the huge room. Peter, eagerly munching on his crackers and slurping his milk, hardly noticed the furry animal. Day by day, Jones moved the rabbit closer and closer. Within two months, Peter was holding the rabbit in his lap, even stroking it while he ate. His fear of rabbits and other furry objects had disappeared. It had been countered, or replaced, by a relaxed state that could not coexist with fear (Fisher, 1984; Jones, 1924).

exposure therapies behavioral techniques, such as systematic desensitization and virtual reality exposure therapy, that treat anxieties by exposing people (in imagination or actual situations) to the things they fear and avoid.

Unfortunately for many who might have been helped by Jones’ procedures, her story of Peter and the rabbit did not enter psychology’s lore when it was reported in 1924. More than 30 years later, psychiatrist Joseph Wolpe (1958; Wolpe & Plaud, 1997) refined Jones’ counterconditioning technique into the exposure therapies used today. These therapies, in a variety of ways, try to change people’s reactions by repeatedly exposing them to stimuli that trigger unwanted responses. We all experience this process in everyday life. Someone who has moved to a new apartment may be annoyed by loud traffic sounds nearby—

systematic desensitization a type of exposure therapy that associates a pleasant, relaxed state with gradually increasing, anxiety-

One form of exposure therapy widely used to treat phobias is systematic desensitization. You cannot be anxious and relaxed at the same time. Therefore, if you can repeatedly relax when facing anxiety-

The therapist then trains you in progressive relaxation. You learn to release tension in one muscle group after another, until you feel comfortable and relaxed. The therapist then asks you to imagine, with your eyes closed, a mildly anxiety-

The therapist then moves to the next item on your list, again using relaxation techniques to desensitize you to each imagined situation. After several sessions, you move to actual situations and practice what you had only imagined before. You begin with relatively easy tasks and gradually move to more anxiety-

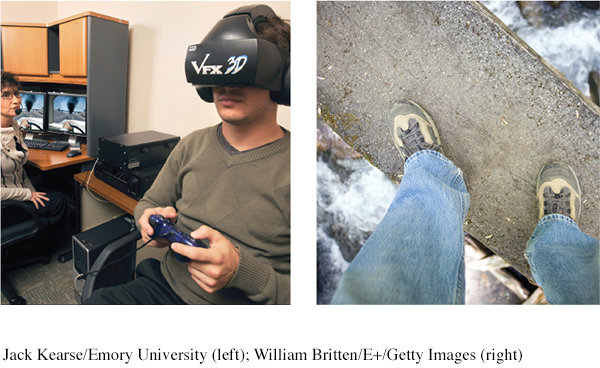

virtual reality exposure therapy a counterconditioning technique that treats anxiety through creative electronic simulations in which people can safely face their greatest fears, such as flying, spiders, or public speaking.

If an anxiety-

AVERSIVE CONDITIONING Exposure therapies help you learn what you should do. They enable a more relaxed, positive response to an upsetting harmless stimulus.

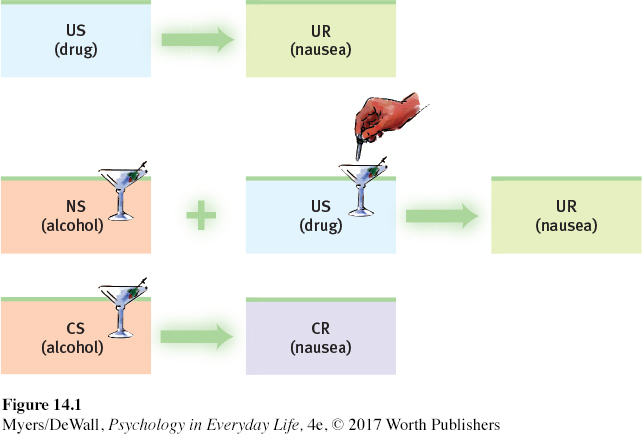

aversive conditioning a type of counterconditioning that associates an unpleasant state (such as nausea) with an unwanted behavior (such as drinking alcohol).

Aversive conditioning helps you to learn what you should not do. It creates a negative (aversive) response to a harmful stimulus.

The aversive conditioning procedure is simple. It associates the unwanted behavior with unpleasant feelings. Is nail biting the problem? The therapist might suggest painting the fingernails with a yucky-

Does aversive conditioning work? In the short run it may. In one classic study, 685 patients with alcohol use disorder completed an aversion therapy program (Wiens & Menustik, 1983). Over the next year, they returned for several booster treatments that paired alcohol with sickness. At the end of that year, 63 percent were not drinking alcohol. But after three years, only 33 percent were alcohol free.

Aversive conditioning has a built-

Operant Conditioning Techniques

LOQ 14-

If you swim, you know fear. Through trial, error, and instruction, you learned how to put your head underwater without suffocating, how to pull your body through the water, and perhaps even how to dive safely. Operant conditioning shaped your swimming. You were reinforced for safe, effective behaviors. And you were naturally punished, as when you swallowed water, for improper swimming behaviors.

Remember a basic operant conditioning concept: Consequences drive our voluntary behaviors (Chapter 6). Knowing this, therapists can practice behavior modification. They reinforce behaviors they consider desirable. And they do not reinforce, or they sometimes punish, undesirable behavior. Using operant conditioning to solve specific behavior problems has raised hopes for some seemingly hopeless cases. Children with intellectual disabilities have been taught to care for themselves. Socially withdrawn children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have learned to interact. People with schizophrenia have learned how to behave more rationally. In each case, therapists used positive reinforcers to shape behavior. In a step-

In extreme cases, treatment must be intensive. One study worked with 19 withdrawn, uncommunicative three-

Not everyone finds the same things rewarding. Hence, the rewards used to modify behavior vary. Some people may respond well to attention or praise. Others require concrete rewards, such as food. Even then, certain foods won’t work as reinforcements for everyone. One of us [ND] finds chocolate neither tasty nor rewarding. Pizza is both, so a nice slice would better shape his behaviors. (What might best shape your behaviors?)

token economy an operant conditioning procedure in which people earn a token for exhibiting a desired behavior and can later exchange the tokens for privileges or treats.

To modify behavior, therapists may create a token economy. People receive a token or plastic coin when they display a desired behavior—

Retrieve + Remember

Question 14.2

•What are the insight therapies, and how do they differ from behavior therapies?

ANSWER: The insight therapies—psychodynamic and humanistic therapies—

Question 14.3

•Some unwanted behaviors are learned. What hope does this fact provide?

ANSWER: If a behavior can be learned, it can be unlearned and replaced by other, more adaptive responses.

Question 14.4

•Exposure therapies and aversive conditioning are applications of _______ conditioning. Token economies are an application of _______ conditioning.

ANSWERS: classical; operant

Cognitive Therapies

LOQ 14-

People with specific fears and problem behaviors may respond to behavior therapy. But how would you modify the wide assortment of behaviors that accompany depressive disorders? And how would you treat generalized anxiety disorder, where unfocused anxiety doesn’t lend itself to a neat list of anxiety-

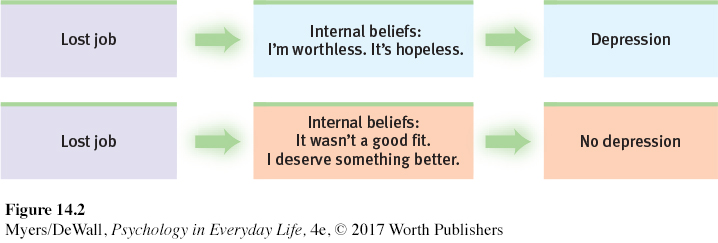

cognitive therapy a therapeutic approach that teaches people new, more adaptive ways of thinking; based on the assumption that thoughts intervene between events and our emotional reactions.

The cognitive therapies assume that our thinking colors our feelings (FIGURE 14.2). Between an event and our response lies the mind. Self-

“Life does not consist mainly, or even largely, of facts and happenings; it consists mainly of the storm of thoughts that are forever blowing through one’s mind.”

Mark Twain (1835–

Beck’s Therapy for Depression

Depressed people don’t see the world through rose-

Cognitive therapist Aaron Beck developed cognitive therapy to show depressed clients the irrational nature of their thinking, and to reverse their negative views of themselves, their situations, and their futures. With this technique, gentle questioning seeks to reveal irrational thinking and then to persuade people to remove the dark glasses through which they view life (Beck et al., 1979, pp. 145–

Client: I agree with the descriptions of me but I guess I don’t agree that the way I think makes me depressed.

Beck: How do you understand it?

Client: I get depressed when things go wrong. Like when I fail a test.

Beck: How can failing a test make you depressed?

Client: Well, if I fail I’ll never get into law school.

Beck: So failing the test means a lot to you. But if failing a test could drive people into clinical depression, wouldn’t you expect everyone who failed the test to have a depression? . . . Did everyone who failed get depressed enough to require treatment?

Client: No, but it depends on how important the test was to the person.

Beck: Right, and who decides the importance?

Client: I do.

Beck: And so, what we have to examine is your way of viewing the test (or the way that you think about the test) and how it affects your chances of getting into law school. Do you agree?

Client: Right.

Beck: Do you agree that the way you interpret the results of the test will affect you? You might feel depressed, you might have trouble sleeping, not feel like eating, and you might even wonder if you should drop out of the course.

Client: I have been thinking that I wasn’t going to make it. Yes, I agree.

Beck: Now what did failing mean?

Client: (tearful) That I couldn’t get into law school.

Beck: And what does that mean to you?

Client: That I’m just not smart enough.

Beck: Anything else?

Client: That I can never be happy.

Beck: And how do these thoughts make you feel?

Client: Very unhappy.

Beck: So it is the meaning of failing a test that makes you very unhappy. In fact, believing that you can never be happy is a powerful factor in producing unhappiness. So, you get yourself into a trap—

We often think in words. Therefore, getting people to change what they say to themselves is an effective way to change their thinking. Have you ever studied hard for an exam but felt extremely anxious before taking it? Many well-

To change such negative self-

| Aim of Technique | Technique | Therapists’ Directives |

|---|---|---|

| Reveal beliefs | Question your interpretations | Explore your beliefs, revealing faulty assumptions such as “I must be liked by everyone.” |

| Rank thoughts and emotions | Gain perspective by ranking your thoughts and emotions from mildly to extremely upsetting. | |

| Test beliefs | Examine consequences | Explore difficult situations, assessing possible consequences and challenging faulty reasoning. |

| Decatastrophize thinking | Work through the actual worst- |

|

| Change beliefs | Take appropriate responsibility | Challenge total self- |

| Resist extremes | Develop new ways of thinking and feeling to replace maladaptive habits. For example, change from thinking “I am a total failure” to “I got a failing grade on that paper, and I can make these changes to succeed next time.” |

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

cognitive-

“The trouble with most therapy,” said therapist Albert Ellis (1913–

Anxiety, depressive disorders, and bipolar disorder share a common problem: emotion regulation (Aldao & Nolen-

CBT effectively treats people with obsessive-

A newer CBT variation, dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), helps change harmful and even suicidal behavior patterns (Linehan et al., 2015; Valentine et al., 2015). Dialectical means “opposing,” and this therapy attempts to make peace between two opposing forces—

Retrieve + Remember

Question 14.5

•How do the humanistic and cognitive therapies differ?

ANSWER: By reflecting clients’ feelings in a nondirective setting, the humanistic therapies attempt to foster personal growth by helping clients become more self-

Question 14.6

•What is cognitive-

ANSWER: This integrative therapy helps people change self-

Group and Family Therapies

LOQ 14-

So far, we have focused mainly on therapies in which one therapist treats one client. Most therapies (though not traditional psychoanalysis) can also occur in small groups.

group therapy therapy conducted with groups rather than individuals, providing benefits from group interaction.

Group therapy does not provide the same degree of therapist involvement with each client. However, it offers other benefits:

It saves therapists’ time and clients’ money, and often is no less effective than individual therapy (Fuhriman & Burlingame, 1994; Jónsson et al., 2011).

It offers a social laboratory for exploring social behaviors and developing social skills. Therapists frequently suggest group therapy when clients’ problems stem from their interactions with others, as when families have conflicts or an individual’s behavior distresses others. The therapist guides people’s interactions as they confront issues and try out new behaviors.

FAMILY THERAPY This type of therapy often acts as a preventive mental health strategy and may include marriage therapy, as shown here at a retreat for military families. The therapist helps family members understand how their ways of relating to one another create problems. The treatment’s emphasis is not on changing the individuals, but on changing their relationships and interactions.John Moore/Getty Images

FAMILY THERAPY This type of therapy often acts as a preventive mental health strategy and may include marriage therapy, as shown here at a retreat for military families. The therapist helps family members understand how their ways of relating to one another create problems. The treatment’s emphasis is not on changing the individuals, but on changing their relationships and interactions.John Moore/Getty ImagesIt enables clients to see that others share their problems. It can be a relief to find that others, despite their calm appearance, share your struggles, your troubling feelings, and your potentially harmful thoughts.

It provides feedback as clients try out new ways of behaving. Hearing that you look confident, even though you feel anxious and self-

conscious, can be very reassuring.

family therapy therapy that treats the family as a system. Views an individual’s unwanted behaviors as influenced by, or directed at, other family members.

One special type of group interaction, family therapy, assumes that no person is an island. We live and grow in relation to others, especially our family, yet we also work to find an identity outside of our family. These two opposing tendencies can create stress for the individual and the family. This helps explain why therapists tend to view families as systems, in which each person’s actions trigger reactions from others. To change negative interactions, the therapist often attempts to guide family members toward positive relationships and improved communication.

Retrieve + Remember

Question 14.7

•Which therapeutic technique focuses more on the present and future than the past, and involves unconditional positive regard and active listening?

ANSWER: humanistic therapy—

Question 14.8

•Which of the following is NOT a benefit of group therapy?

more focused attention from the therapist

less expensive

social feedback

reassurance that others share troubles

ANSWER: a

To review the aims and techniques of different psychotherapies, and assess your ability to recognize excerpts from each, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Mystery Therapist.

To review the aims and techniques of different psychotherapies, and assess your ability to recognize excerpts from each, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Mystery Therapist.